Archive for August, 2016

Answering big questions through statistics

Resiliency testing is just one example of many research projects Dr. Erin Buchanan, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State University, has published in recent years. She collaborates with undergraduate and graduate students in her statistics lab as well as with a clinical psychologist at University of Mississippi, Dr. Stefan Schulenberg, on many projects regarding the meaning in life.

“How does meaning in life affect negative life outcomes? That’s the big, broad question. Then we narrow it down to, how does a scale work in predicting negative life outcomes? Does it work the same way for everyone?” said Buchanan. “By negative life outcomes, we mean depression, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, drinking – those sorts of things.”

Clinical people say this a lot, “The right therapy for the right patient at the right time,” or something to that effect. Computer-adaptive testing is built on that. “The right question for the right person at the right time.”

Adding technology to the equation

Buchanan’s role in research projects is to develop scales, test the scales to see if they measure what was intended, and to analyze the variance across demographics. Currently, she and her students are in the midst of testing 47 unique scales with students in introduction to psychology classes. She also collects results through MTURK, Amazon’s answer to incentivized testing.

As a daughter of two computer programmers, she said she felt like the black sheep entering the field of psychology, until she realized that as an experimental psychologist focusing on quantitative analysis, she spent much of her time programming, too – in approximately 12 different languages.

“I’ve always been good at math. I knew I never wanted to work directly in a helping profession. That was never my goal,” she said with a laugh.

Just the way you phrase things can change whether a respondent will say yes or no. Just because it’s culturally relevant.

One of the most prominent projects for Buchanan is to develop a computer-adaptive test. This test starts with an average score, but depending on how a respondent answers, the following questions may be more positive or negative, or might increase or decrease in difficulty.

“Social desirability can come into play, where people will go, ‘Oh, you want me to say positive things,’ or you end up with all happy or all negative answers, and you don’t get anything in the middle,” she explained. “We’re trying to statistically stretch the scale out so we might be able to better predict the negative-life outcomes that come with that.”

Answers divided by race

In the early 2000s, the south suffered two major disasters. After Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill, Schulenberg, director of the Clinical-Disaster Research Center at Ole Miss, contracted with Buchanan to test the resiliency of the people of the area.

“I hear this a lot from clinical students, ‘Why do I need statistics? I just want to help people.’ My answer is, ‘Because you have to be able to read these articles and understand the implications the variations in responses people make.'”

“We have a primary focus in disaster mental health and a secondary focus in positive psychology,” said Schulenberg. “Dr. Buchanan has been a tremendous asset to our team for a number of years incorporating sophisticated statistical analyses.”

The resiliency scales were found to be valid and effective, but analysis showed differences between white and black respondents.

“While we end up with the same overall score, white participants were much more likely to have a real short spread of scores. They would only pick the middle, while the black participants would pick the entire range,” she said. “If you’re black in Mississippi you’re much more likely to be one or two steps below socioeconomically. Obviously that’s going to matter for resiliency, right? We were trying to argue that the effects weren’t due to innate resiliency of people, but more due to circumstance.”

Previous research had shown that culture-fairness plays a part in standard and computer-adaptive testing, sometimes resulting in artificial differences because respondents inferred something into the question that might not have been intended. Similarly, Buchanan noted that black people from an early age learn a different dynamic of power and authority, causing differences in way they may perform on tests. So, word selection is key – whether it’s a test about your resiliency or a statewide mandated comprehension test, the testing agent desires representative results.

An everyday life of Biblical proportions

“The house I grew up in and every school I went to was destroyed,” said Matthews. “Much of me went away in the sky, and yet I was able to go back down there and identify what was remaining of the structure that was my childhood home.”

Matthews took a picture of the ruins and uses it in class as a way of talking about how space is still present in our memories. This speaks to his area of expertise: the history and culture of the Biblical era. Though physical remains may be few, the everyday lives of the people from this time can be better understood by studying the stories and artifacts that they left behind.

‘What the devil are they doing?’

How do we learn more about the ancient world? This is one of Matthews’ research questions. He says it’s important to understand that we tend to filter everything through our modern scope.

“We are trying to find out what the devil they were doing. Unfortunately, this often means applying our modern viewpoint and totally skewing the whole thing.”

Biblical narratives, like most stories, assume that the audience shares a defined set of social understandings or customs. When we don’t know what these customs are, we must use several different methods to try to discover them.

“I have made good use of modern research and analytical methods in the social sciences —sociology, anthropology, psychology, communications — to evaluate the ‘human moments’ in the narratives,” said Matthews. “For example, when I examined the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38, I looked for the social cues in the story: clothing, marriage status, power relationships, gender, speech patterns and the physical placement of the characters.”

Matthews applied these methods when writing and researching his most recent publication, the fourth edition of “The Cultural World of the Bible: An Illustrated Guide to Manners and Customs.” It is one of 17 books he has authored, and he has published numerous articles on the subject as well.

Putting together a large puzzle

“When we say cultural world, what it basically says to people is that we’re going to talk about everyday life. What did they eat? What did they wear? How did they celebrate? What were their burial practices? What kind of weapons did they use?” he said. “All kinds of topics like that.”

There are several ways we can learn the answers to questions like these: written records, including the Biblical text and extrabiblical documents; physical remains such as tomb paintings and grave goods, garbage heaps, and the ruins of buildings, which are studied by archaeologists; and the study of both modern and ancient cultures via analogy.

“Reconstruction of the world of ancient Israel is like putting together a large puzzle,” said Matthews. “Some of what I included in the book came from my own travels in the Middle East, some from basic research and discussion with colleagues, and some from studying how other authors shaped their treatment of the subject.”

Talking about talking: analyzing conversations

Matthews, who has been a Biblical scholar for more than 30 years, has also recently focused on the conversations that occur in these Biblical narratives and what they can tell us about the characters and their daily lives.

“There is a lot of conversational analysis in communications, sociology, anthropology and psychology,” said Matthews. “I got interested in seeing how the different disciplines analyzed conversation, but, of course, what I’m working with is text. I have narratives with embedded dialogue.”

“It allowed me to develop a richer understanding about the setting of the story, the human drama associated with a childless widow, the importance of clothing as a social marker and the role that place—physical location—holds in determining how humans interact.” (Matthews on studying the human moments in narratives.)

Matthews studied the way these disciplines researched conversations, which mostly consisted of analyzing live conversations. He applied many of the techniques and concepts they used to the narratives he was studying and was able to discover previously unknown contexts. His book, “More Than Meets the Ear: Discovering the Hidden Contexts of Old Testament Conversations,” was published in 2008 and led to a journal article in 2014, “Choreographing Embedded Dialogue in Biblical Narratives.”

Matthews graduated from Missouri State in 1972 with a bachelor of arts degree in history, and received his masters and doctorate in Near Eastern and Judaic studies from Brandeis University in 1973 and 1977 respectively. He has spent most of his career focused on the historical aspects of religious studies, and looks forward to continuing his studies on ancient Biblical culture and writing about what daily life was like thousands of years ago.

Further reading

Small particles, big impact? Exploring how nanomaterials decompose

Silver, known for antibacterial and anti-odor properties, may be in everything from athletic wear to cutting boards. Zinc oxide, which prevents sun damage, has been used in sunscreen and woven into fabric for clothing. Carpet may be treated with nanoscale materials that prevents it from absorbing spills. Carbon-based nanomaterials are found in cell phones and televisions.

One thing is sure: The trend of nanotechnology means we are all more likely to buy goods with these tiny particles, and, later, dispose of these products.

What’s less certain is the affect of these nanomaterials on the environment as these goods decompose in landfills.

“I wanted to do research with undergraduate students, not just students studying for a PhD. Here are Missouri State, some of my best research has been done by undergraduates.” — Dr. Adam Wanekaya

Dr. Adam Wanekaya, associate professor of chemistry, has researched nanomaterials since his days as a doctoral student in the early 2000s.

For the last three years, he has been leading a project with undergraduate and graduate students at Missouri State who are studying how nanomaterials age in an accelerated weathering chamber. The research shows how these particles will react in conditions similar to those they would experience outdoors.

“What is the fate of those particles after three, 10, 20 years? We want to make sure they don’t contribute to diseases such as leukemia, or cause harm to plants, animals or the environment,” Wanekaya said. “Some of us recall how asbestos was previously thought to be a wonder material, only to later realize it was the cause of many deadly diseases.”

African collaborations

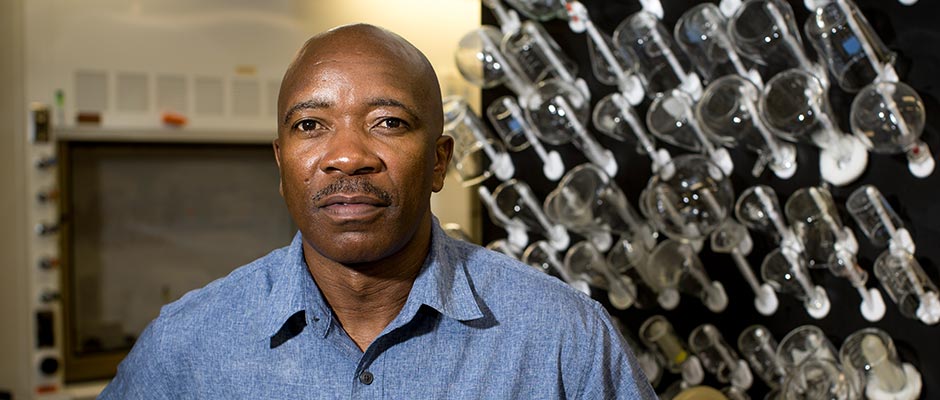

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is originally from Kenya, and came to the U.S. for doctoral studies. He started working at Missouri State in 2006. He is currently part of the Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program, which encourages collaboration between scholars from Africa who now live in Canada or the U.S. and scholars who currently live in Africa.

Wanekaya traveled to a university in Nigeria for six weeks in 2015. One scientist he met there, who works with solar cells, came to Missouri State in January 2016 and planned to stay for six months to engage in research on campus.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Creating conditions that mimic the outdoors

At least once a week, senior Molly Duszynski heads into a chemistry lab at Temple Hall.

First, she attaches carbon nanotubes to glass slides.

Next, she takes the slides to an accelerated weathering tester, where they fit into holders designed for them.

“It has been really awesome to learn about carbon nanotubes and the overall process of real research.” — Molly Duszynski, biochemistry/microbiology double major

Now, the chamber is closed. It’s time for Duszynski to make decisions about what kind of conditions the slides will face. The chamber has UVA-340 bulbs, which provide the best possible simulation of sunlight. It is also attached to a tank that holds water free of minerals or impurities. She, Wanekaya or others on the project may adjust lighting, humidity, temperature and more to simulate sunlight, rain and dew. The chamber can create conditions for night, evening, afternoon or morning, or cycle through those.

In a few days or weeks, the machine can reproduce the decomposition that would occur in months or years outdoors.

Wanekaya’s team has chosen to mostly focus on conditions that are slightly hotter than normal, in order to see what the carbon nanotubes would do if they were in a landfill in a part of the country with high-intensity sunlight.

They chose carbon to study first.

“This is a good basic material because we can predict a bit about carbon’s behavior,” Wanekaya said. “We are starting with something more simple before we move on to something a bit more complex.”

Approximate conversion chart

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula for how many hours in a weathering chamber equals a time period in the outdoors, according to Q-Lab (the company that makes the QUV Weathering Tester used in MSU’s chemistry lab). That’s because the relationship between tester exposure and outdoor exposure has so many variables, such as geographic latitude of the exposure site, altitude, random variations in weather from year to year, etc. One recent graduate student in Wanekaya’s project, however, was using this approximate ratio: 2,100 hours of weathering tester exposure = About one year in the Florida sun

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Preliminary results, collaborative papers

Wanekaya says the research is yielding some preliminary results.

The team can see that the shapes of the carbon nanotubes change after treatment in the chamber. Before treatment, the nanotubes are more or less linear. After, they are coiled. Using various technologies, the team has shown there are other substantial differences between groups of control nanotubes, which are not subjected to tests, and nanotubes that have been aged.

“Now, we need to find out whether those changes are good, bad or neutral. That’s our next step,” Wanekaya said.

The team shared a tested group and a control group with colleagues in the Missouri State biology department. Those researchers exposed yeast, bacteria and other cells to both the control group and the aged group of nanotubes. They wanted to see if either group of nanotubes was potentially toxic to those materials.

One team found that treating yeast with either aged or control carbon nanotubes was significantly toxic to the yeast cells. Results of that study have been submitted for publication to the Journal of Nanoscience and Technology.

No significant differences were observed in bacteria and plants exposed to both the aged and control carbon nanotubes.

Wanekaya plans to keep working with these tiny particles.

“Nanomaterials are very exciting. They have novel properties that can be used for so many things.”

How small is nano?

In the International System of Units, the prefix “nano” means one-billionth. Therefore, one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. It’s difficult to imagine just how small that is, so here are some examples:

- A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick

- There are 25,400,000 nanometers in one inch

- A human hair is approximately 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide

- One nanometer is about as long as your fingernail grows in one second

Source: United States National Nanotechnology Initiative

Wanekaya’s other research interests

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is seeking many ways to use nanotechnology to benefit humans and the environment. He is involved in research regarding:

- Cancer treatment (part of a team that received a grant from the National Institutes of Health)

- Cancer detection

- Detecting and removing toxins from the environment

For more about his work regarding cancer, see a past Mind’s Eye story about one of Wanekaya’s collaborators.