Archive for September, 2016

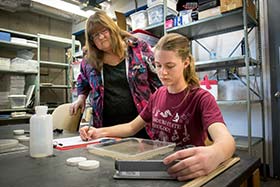

She studies swimming and scampering species

Although she sees the beauty in the way they move and communicate, so much of their lives are hidden from the average hiker. Sometimes these animals are hiding from predators, while other times, they only seem hidden due to their small size and cryptic colors: Terrestrial and stream salamanders are only the size of an earthworm.

So, to me, it’s incredible. I have to emphasize, we’re talking about an animal the size of an earthworm and yet they can do all of this incredible stuff.

Mathis argues that these species each are intricate and fascinating despite their size.

“We have all these ideas about the challenges animals encounter and how they have adapted to meet those challenges,” she said. In a natural habitat, these challenges include: avoiding predators, finding mates, dealing with competition, and locating good habitats and food. “What can animals do to increase their probability of survival and reproductive success? That’s really the bottom line as far as biology is concerned. Everything, from the way your cells work to the way ecosystems work boils down to this.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Communicating like a terrestrial salamander

Even if you find these creatures a little creepy, Mathis says they can serve as a model for addressing questions about sensory behavior in other species, including humans.

In the field of behavioral ecology, or the study of how animal behavior evolves due to ecological changes, she delves deeply into aggression and territorial behavior, predation responses and pheromones. The methods of communication she’s seen are far more sophisticated and complex than people might assume.

Terrestrial salamanders, for instance, which abound in forests, are ideal for studying issues of competition and territoriality, according to Mathis. They defend territories, fight over patches of forest floor to maintain access to food sources and females guard their eggs.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

“It turns out that there’s some interesting social behavior going on. In some species where males and females form pair bonds, they pay attention to whether their partners have been cheating on them.”

Unlike a peacock that can flaunt its feathers or a frog that can croak its displeasure, these terrestrial salamanders don’t advertise themselves visually or vocally. Instead, they produce territorial pheromones like many mammals, and Mathis studies how these salamanders can communicate chemically only by olfactory cues.

She, in collaboration with former graduate student Ben Dalton, found that through these pheromones, the animals can discern whether the other animal is of their own species or a different species. They can also tell sex, whether the other animal is familiar to them and whether it’s from a neighboring or adjoining territory.

“Then we start getting into weird stuff, like they can tell what type of diet the other animal has been eating: high-quality or low-quality? They can tell whether the other animal is parasitized or not, which might tell them something about the condition of their opponent, and it might tell them if they should hang out with that other individual. Then they can differentiate and respond differently in each context.”

The study became the basis for Dalton’s thesis, as well as a conference presentation and an article in Chemoecology. Over the years, Mathis and her students have co-authored over 70 journal articles and book chapters, made over 100 conference presentations and received over $125,000 in external grant funding for her work.

Photo by Bob Linder

Lab and field

At Missouri State, many biology undergraduates and almost all graduate students perform research under the supervision of their advisers. Mathis enjoys exploring the answers to the research questions her students pose.

Though a microscope isn’t needed to study the responses of these animals, she and her graduate students have had to employ creative techniques to follow some of these animals in her studies.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

“We have done some field work, including snorkeling and following darter fish while using an apparatus to expose them to the chemical cues we introduced in the water, which was pretty cool,” she said. “And we’ve gotten verification that they were responding the way we’d seen them respond in the lab.”

While snorkeling through streams and ponds, digging past water table levels in streams that have run dry, and camping out next to the waterways to observe the nightly behaviors of these animals is exhilarating, most of the work takes place in a lab that simulates their natural habitats. Their practicality is a primary reason these animals are Mathis’ first choice subject in her 350 square foot lab.

“For some of them, their natural habitats include burrows, so being in a really small space is something they like,” she said. “They also adapt really well to the lab and show no signs of stress with people walking in front of the cages.”

Sound the alarm: Big discoveries

Her post-doc work led her to Canada, where she continued her chemical communication research, but she expanded it to learn more about interactions between predators and prey. More specifically, she looked at how chemical cues help stickleback and minnows (more appropriate research subjects for that region) survive predatory encounters. When minnow skin is scratched by a predator, it releases an alarm pheromone, which conveys to other animals that there’s an active predator in the area, causing the fish to flee, seek shelter or school tightly together.

“Clearly minnows that respond to that chemical are going to increase their likelihood of survival. But one of the most eye-opening discoveries from the study was that there could be cross-species responses,” she said. “It’s not only that minnows can respond to alarm cues from other minnows, but they could also respond to other really distantly related fish, like stickleback. They can respond across very large taxonomic divisions.”

At Missouri State, she and undergraduate student Michael Lampe demonstrated that terrestrial salamanders can respond to alarm cues from earthworms, which is significant since they have similar predators. And current graduate student Kelsey Anderson is looking at the responses of darters – little stream fish – to salamander alarm cues.

“It is not surprising when animals that are closely related intercept information from each other and respond appropriately. It’s a bit shocking, though, when animals that are very different from each other can interpret signals from each other,” she said. “The ability of animals to eavesdrop on signals sent by individuals in other species can be a great benefit by leading to increased survival in the face of predation.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

New questions

Though she started some of this work as early as her dissertation, she’s conducted follow-up studies using Ozarks species since she came to Missouri State in 1993. It’s a “treasure trove of salamanders,” she jokes.

At that point, she also decided to merge some of her previous interests and studies to understand how predation risk influences territorial behavior and answer this question: Does experiencing high risk of predation influence the way an animal defends its territory?

Photo by Bob Linder

This is the premise for more studies with graduate student Jenny Parsons. They found that individual salamanders in their own territories continued to defend their territories even upon predation risk, but salamanders in foreign territories became more submissive following exposure to a predation risk. A new student, Sara Heimbach, is continuing this research.

One study always leads to the next – innate curiosity is essential to being a scientist, said Mathis – so she then studied antipredator behavior in a pond breeding salamander, the ringed salamander, which is a species of conservation concern in Missouri.

The free-swimming larvae of the ringed salamander are just like tadpoles, and are in grave danger in the pond with major predators like birds, other salamanders, snakes and aquatic insects surrounding them. But how do these larvae recognize predators and survive until metamorphosis? Smell, said Mathis.

In addition to communication and territoriality, Mathis has also examined how these animals learn. For instance, how do they learn which animals pose a threat?

“We’ve deduced from what we’ve seen in a couple of different species that they’re actually learning from each other – so social learning. And we’ve got a couple of studies that show they can learn while they’re still embryos,” she said. “These eggs are basically bathed in information; many smells are surrounding them. We had one experiment that showed that if you housed the eggs in water that predators have been in, the larvae spent more time hiding in vegetation once they hatch than if they weren’t exposed to cues from predators while they were embryos.”

Photo by Bob Linder

Environmental impacts

When studying chemical communication in these animals, the naked human eye usually can’t see the emitted pheromone. However, for one salamander species in particular, the hellbender, it’s a dramatic frothy white secretion.

Missouri is the only state to call both currently recognized subspecies of hellbenders home, and Mathis has been researching them since 1997. In the last few decades, though, the population of hellbenders in Missouri has declined more than 75 percent.

“When you see these animals and how fabulous they are and how they deal with regular challenges, and then you see environmental challenges being layered on top of that, it’s a huge concern. You have to wonder how long they can continue dealing with these new challenges. It has quite significantly impacted the way I study animal behavior.”

Agricultural runoff and pollution are just two of the concerns for waterways, and Mathis found that hellbenders are great models for environmental studies not only due to their practicality, but also their pickiness for the perfect environment. She noted hellbenders require fast-flowing, cool, clear water to get the proper amount of oxygen, so they serve as an indicator for environmental health and subsequently, public health.

“Biology – it’s very complex in the way that every detail has to work together to produce an outcome, and that’s what interested me in the first place,” she said.

My work is the kind of thing that people generally have some kind of familiarity with because it’s covered on nature documentaries, and people love that stuff!

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

Further reading

A mother – and a computer – can differentiate a baby’s cry

Brahnam, a professor of computer information systems at Missouri State University, has multiple interests in the field of technology. She collaborates on many of these projects with Dr. Loris Nanni from the Università di Bologna in Italy – a collaborator she has never met face-to-face.

One of her many research projects was to develop the machine learning algorithm called the Infant Classification of Pain Expressions. ICOPE was designed to recognize distressed facial expressions in neonatal babies, and it was the first of its kind. Infants at Mercy hospital were photographed while they were experiencing a number of benign nonpain stressors and an acute pain stimulus (the heel lance needed for the state-mandated blood exam).

“Are they in pain or not? You can’t tell because they cry all the time,” joked Brahnam. Furrowed brows and certain mouth or eye shapes can be tell-tale signs, but this system helps to identify pain even if nurses are busy or face blind.

Now she’s preparing to look deeper with the use of video equipment which will not only see the expressions but will measure heart rate, respiration rate or even changes in pixel colors to enhance the ability to classify pain expressions.

Cry without pain

The expressions in these photos were used to help Brahnam develop the Infant Classification of Pain Expressions (ICOPE) system. Infants at Mercy hospital were photographed while they were experiencing a number of benign nonpain stressors and an acute pain stimulus. Photos provided by S. Brahnam.

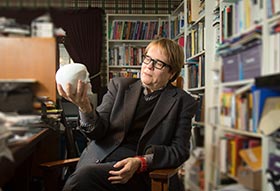

Technology can be art

Photo by Bob Linder

As a former artist, Brahnam has always been interested in faces and expressions, so when she went back to school, her dissertation actually was to build an artificial artist. In order to do so, she had to train a computer to recognize specific traits and teach it to see people like human beings see people.

First, she developed a dataset of faces that people judged according to a set of traits, and then trained machines to recognize people that looked trustworthy versus untrustworthy, dominate versus submissive, and so on.

“I used facial recognition technology to classify faces according to people’s impressions of faces. I then produced an algorithm to generate from this model novel faces that were calculated to produce specific impressions on people. Artists do something similar when they draw people,” she said. “In this research I was able to show that it was possible for machines to see the social meanings of a person’s physical appearance and reproduce it – something a chatbot might want to do. People adjust their appearances for different occasions. Why not chatbots?” This is a technology Brahnam calls smart embodiment.

But how do you teach a computer?

It all starts with building an algorithm, a training set and a testing set. You begin by showing the computer something from the training set – handwritten letters, for example. The system will guess based on the information pre-programmed in the algorithm. If incorrect, adjustments are made until it can guess correctly. According to Brahnam, the testing set is used to see how well the computer can extrapolate information or how well it can learn when given something new.

“We now live in a world of lots of data – huge stock piles of data. Our brains have not evolved in a big data environment. We can’t handle lots of different data and this is where machines can be very good.”

A ‘cathedral of classifiers’

While processing lots of big data isn’t a human’s forte, Brahnam noted that we are more capable of distinguishing patterns than machines, especially in noisy environments, “because we have this evolutionary history behind us.” Infants and toddlers, she explained, find recognizable patterns, shapes and letters even in a cluster of clutter.

Much of her work deals with developing and improving multi-classifier systems that have many different learning algorithms working together on lots of different data. For example, to detect cancer, there could be a machine with many classifiers running simultaneously, each individually responsible for analyzing demographics, imagery, laboratory readings or instrumental readings. Putting the analyses together, a doctor could get a full picture of whether cancer was present.

“If we have gigantic systems working together, we think that we can make a general purpose classifier system, at least for certain classes of problems. That’s another thing that we are working really hard on: this gothic cathedral of classifiers.”

One way that a multiclassifier system works is for different classifiers to look at different aspects of a problem or data set. The different conclusions are then averaged for a final decision. The story of the blind men and the elephant illustrates the value of this approach. Some people touch the tusk of an elephant and say, “Hmm. It’s made out of stone.” Another person touches the tail and says, “No, it’s fluffy. I think this is the end of a drapery.” Another person hits the legs and says, “This is definitely a tree trunk.” That would be kind of like the classifier systems. Each one is getting different information that if you combine the total picture, you might get an elephant.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Bob Linder

Further reading

Winding road that led to destiny

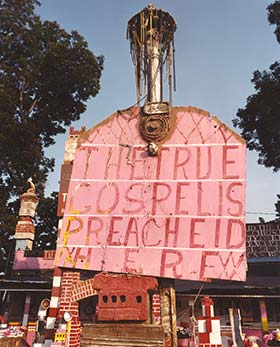

In his book, “The True Gospel Preached Here,” Bruce West shares the story of one couple who shared their lives with many.

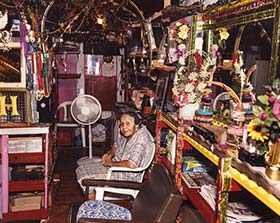

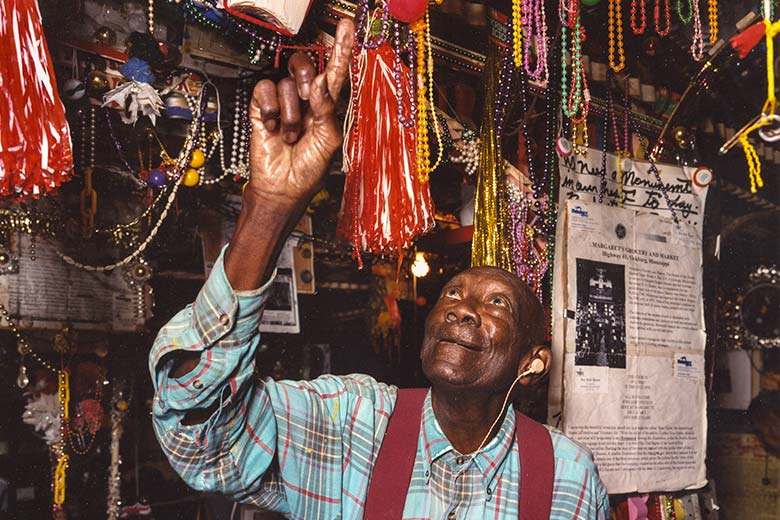

To his students, he always likens the camera to a magic carpet, which could lead you on a wonderful journey of discovery. And when he found this run down grocery store turned roadside attraction – and school bus turned chapel – he was captivated.

“I wanted to show that to be poor isn’t a crime and that economically disadvantaged people can lead fulfilled and inspired lives, even more fulfilled than rich folks. That certainly was the case with the Reverend H.D. Dennis. He created his own universe that people all over the world came to visit. That was pretty amazing.”

Seeing the world through a new lens

For approximately 20 years prior to his excursion to the south, West had been gaining recognition, exhibiting gorgeous black and white landscape work and housing collections in museums from the Midwest to Verona, Italy. This project was a literal departure from that in just about every way. These characters – the Reverend and Margaret – were as colorful as the folk art palace they had decorated all around them with banal baubles, beads, hair ties and trinkets.

“Mrs. Margaret Dennis Rest in Grocery” 2008. Photo by Bruce West

Margaret’s Grocery, which sold kitchen staples to the surrounding community, was overtaken by the decoration that the Reverend created there. He claimed they were visions from God, and the signs, altars, installations and bus were a ploy to pique curiosity so he could attract visitors to share the gospel.

“If God is in the details, West makes sure to leave nothing unseen here through his sacred photographic language, helping us feel near-scriptural depth through the explicitness of the particular.” — From the forward of “The True Gospel Preached Here”

Experiencing the septuagenarians’ passion for evangelism and art changed this passerby into a member of the family for the Dennises’ final 18 years on Earth.

“Every year I kept going back, and it was always different. I started to realize that this was something really important because there aren’t going to be people like this anymore – people who devote their lives fully to the spiritual and the aesthetic.”

“Alter, Inside Bus/Church” 2007. Photo by Bruce West

As West grew closer to the couple, they began corresponding, and he began to get more deliberate in what and how he captured their lives on film. He foresaw the possibility of a book that respectfully depicted the work of the Dennises, but he knew his work also told a story of race, age, religion and class.

“It was such a privileged experience because, eventually, they called me their white son.”

“Rev H.D. Dennis Points to God” 2006. Photo by Bruce West

Faith focus

Cheekily, West calls himself a lapsed Catholic, but in all seriousness, he attributes his spirituality as the tie that binds all of his projects together. From showing the majesty of a landscape, to portraying the Dennises as they ‘practiced living perfect for God,’ to looking at religious strife in a series on the The Troubles in Northern Ireland, his photography exposes a longing for the divine.

“True Gospel Preached Here” 2007. Photo by Bruce West“One of the benefits with film was I’d have to wait until I got it processed. It gave me a distance from it. Sometimes it could be years and I’d come back and say, ‘oh this is the real surprising one.’” — Bruce West

Though the constant underlying theme might be faith, he is always challenging himself to explore it in a new way. For his latest endeavor, The Small Town Project, he has left the comforts of film and moved to digital. This former East Coaster is trolling around small towns in Missouri to learn more about the state and the humanity of its inhabitants.

“If you’re a scientist you’re trying to learn something new about the world. The same thing with photography. I always approach it from that point of view. Also, as you’re doing that, you’re learning about yourself.”

Further reading

Music restores harmony in the lives of those with aphasia

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.

Dr. Alana Kozlowski, Missouri State University communication sciences and disorders assistant professor, studies people with an acquired communication disorder called aphasia. She has been working to develop a way for those with aphasia to have a rewarding, relaxing activity in an environment where those who struggle with verbalization are back on equal footing with those who care for them.

At the same time, she wanted to provide her graduate students with an opportunity to conduct qualitative research. So the Canada native started a community music-making group. She chose this activity because aphasia is caused by an injury to the left hemisphere of the brain, the area that controls language. The right hemisphere controls response to the components of music – melody, harmony and pitch. Participants in the music-making group could hum, tap, sing, or “just be among friends.” No prior musical experience was necessary.

Instead of focusing on what people with aphasia cannot do, Kozlowski and her graduate students are emphasizing what those who struggle with verbalization can do and they are building on those strengths. They are currently using a tool developed by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the Quality of Communication Life Scale, to determine if participating in the music-making sessions has helped people with aphasia gain confidence in their communication abilities and/or living with their communication disorder.

Will people with aphasia be willing to engage socially and feel better about it because of this shared successful experience?

Finding the words again

Someone who entered the room would see 15 people singing “Amazing Grace” and never guess that six of them would not be able to make a simple request such as asking for salt.

Before coming to MSU in 2010, Kozlowski worked for 15 years with individuals with aphasia in rehabilitation and acute-care settings, where her long-range goal often included helping clients “get their words back.” Although she found this type of speech-language therapy “incredibly rewarding,” Kozlowski began to consider what quality of life she could shape for an individual that would be reasonable and patient-driven.

“Often my goal as a speech-language pathologist was to help clients effectively and efficiently express their wants and needs. However, I began to question whether having a shared social experience with or without words may be equally important. Maybe a shared social experience was more important than words to a 75-year-old who had been married 50 years,” she mused.

During the 2015-16 academic year, a small group of people with aphasia and their caregivers joined “team Koz” twice a month to make music in a room at the Springfield-Greene County Library Center. Someone who entered the room would see 15 people singing “Amazing Grace” and never guess that six of them would not be able to make a simple request such as asking for salt.

Embracing the challenge

Clara Keller, graduate student and harpist, addresses the group.

Harpist Clara Keller, a music therapist from Poughkeepsie, New York, who is pursuing a master’s degree in speech-language pathology from MSU, accompanied the singers. “I learned how powerful music is as a tool for language and social interaction when speech is lost,” she noted.

A participant whose wife experienced a stroke said she looks forward to the music-making sessions. “In our circles there are not any other people with aphasia,” he stated. “She doesn’t feel like she stands out here. Music comes out when words don’t.” The caregiver for a man who was a popular jazz musician prior to his stroke added that singing in the group enabled him to make friends and gave her an activity to do with him that allowed her to share what he was feeling at the moment.

The students’ research indicated the caregivers did not view the additional time commitment as a burden if it made their persons with aphasia feel integrated into a group and happier. The most surprising finding, Kozlowski said, was that the individuals with aphasia preferred to sing songs with words rather than songs without words, regardless of the difficulty of the song, and preferred to sing rather than play an instrument.

During the first round of sessions Kozlowski and her students validated the value of the sing-alongs in building camaraderie and providing a stress-free opportunity for those with aphasia to successfully communicate with their caregivers. The students presented their research at the Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention in April 2016.

“People keep coming back to sing,” Kozlowski added with a smile. “We’re having fun. Can we capture why? Will people with aphasia be willing to engage socially and feel better about it because of this shared successful experience? If so, why would they not get the same positive experience in the store or in church?”