Picking the right literature to counter aliteracy

Illiteracy is a concern for Dr. Sabrina A. Brinson, who advocates for learning those skills early and reinforcing often. But she is equally concerned about the plague of aliteracy – a term used to describe having the ability to read but lacking the desire and motivation.

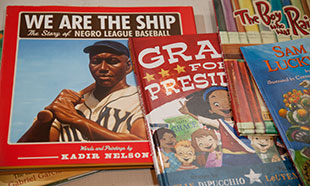

Brinson is a Diversity Fellow and a professor of childhood education and family studies at Missouri State, and part of her response to this problem was the establishment of Boys Booked on Barbershops and Girls Booked on Beautyshops in 2004. These are community-based programs set up in neighborhoods and communities all over the United States. Professional organizations – currently more than 20 of them nationwide – partner with Brinson and locate a barbershop, beautyshop or other community location to establish a reading nook.

Don’t clean out your garage to donate books to this great cause, though.

Don’t clean out your garage to donate books to this great cause, though.

She researches the demographics of the shops, communities, patrons and asks pointed questions about the abilities of children who visit the shop. She stays up to date with all the latest literature for children ages 1-18 and tailors the reading nook recommendation to the specific shop’s needs – all of this in hopes of making the books more engaging and interesting to the children and families who read while they’re waiting.

“How do I know it works? One of the most reinforcing things is that children want to take the books with them,” said Brinson.

While these nooks could be in any community the professional organizations wanted to sponsor, they often show up in more diverse communities. This fits right in with her three main research focus areas: diversity, multiculturalism and social justice with an emphasis in African American studies; culturally responsive literature; and the social, emotional and moral development of children.

“When people refer to diversity and culture, we tend to have tunnel vision,” said Brinson. Instead of diversity being synonymous with race and culture, it’s gender, socioeconomic status, religion, language, vernaculars, and so much more, according to Brinson.

In that vein, she looks at culturally responsive literature as a way to engage readers and improve literacy.

“It’s important for people of any culture to see positive reflections of themselves. But it’s also equally important for people to have views into the lives of others,” said Brinson.

One study Brinson conducted with teachers asked them to identify two books in their library that showcased a variety of multicultural and diverse characters as the main characters.

“Just two books – and they (the teachers in the study) couldn’t do it,” Brinson said. From that, she reasoned that the teachers were not incorporating diverse literature into their students’ studies, which could lead students to feel insignificant. “What it says to others – the ones who are represented in the story – it lulls them into a false sense of superiority,” added Brinson.

“How do I know it works? One of the most reinforcing things is that children want to take the books with them.,” – Dr. Sabrina A. Brinson

Bullying and stigmas

This sense of superiority can lead to horrific outcomes, like bullying. Brinson conducted research on females bullying males through interviews with 21-54 year old men who had been victimized in their younger years, often in the lunchroom and between classes.

“People are starting to say, ‘hey, our girls aren’t so sugary sweet and so nice,’” Brinson said. “Every single man I interviewed could recount those acts of bullying as if they’d happened yesterday.”

Through primarily mental abuse, the females gained control over the males they bullied, and the men recounted the emotional turmoil, the frustration of it being socially unacceptable to retaliate against a female, and the feeling of helplessness for fear that no one would believe them.

As part of a research team for positive behavior support, Brinson also helped establish a behavior change program at a Florida middle school for students in special education classrooms. The program – a self-monitoring program, which taught students how to stop themselves before they revert back into their disruptive behavior patterns – was developed to reintegrate the students into general education classrooms and to overcome the stigma that is often associated with special education.