The 20th and 21st centuries have given rise to many new forms of art, and one of the most intriguing is international art. International art is made by people of indigenous cultures and that is inspired by traditional themes and styles, but uses European media and methods for making the art. Four paintings in this group, for example, are made by an artist inspired by Zulu heritage, but using the European media of gouache (pigment mixed with gum arabic) on darker-colored watercolor paper.

The fifth painting in this group is made by a Haitian artist, but using the European media of oil paint on canvas. Haiti is a country founded by self-liberated African slaves who led a successful insurrection against French colonial rule. This country is still largely populated by the descendants of the insurrectionists, and these people carry on many traditions and cultural practices originating in Africa; they are thus a strong part of the African Diaspora.

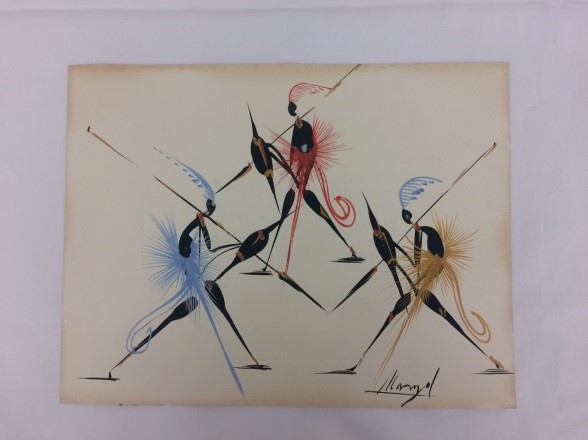

by Manny L

Zulu culture

20th century

Gouache paint on watercolor paper, L. 30 cm x H. 23 cm x W. 1mm

BFPC collection #2012.44a

This painting illustrates three figures wearing traditional Zulu clothing. This consists of an ibheshu, and a slene, lower-torso garments made from animal hide and fur that wrap around the waist. They also wear a married man’s headpiece, which can either be a large feather, like the figures in the painting are wearing, or a headband made of animal fur.

The figures are participating in a traditional activity called stick fighting. This activity originally started out as a way to train warriors, where young men could show off their courage and skill, but over time, stick fighting also became a way to settle fights and arguments. There are strict rules in stick fighting, as eye contact must be maintained, and there is no stabbing allowed. The fight is over as soon as blood is drawn, and then the winner tends to the loser’s wounds.

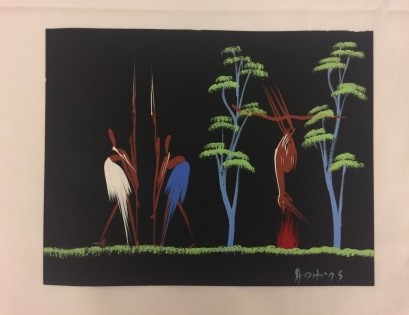

by APHA

Zulu culture

20th century

Gouache paint on watercolor paper, L. 30 cm x H. 23 cm x W 1 mm

BFPC collection #2012.44b

This painting differs from the others in having a colorfully painted, striped background. In the scene depicted, two figures watch five large birds. The figure on the left has across his shoulders a long stick with a bag on each end, a traditional way to carry heavy items for a long distance. As the figures have no spears or shields, they are not hunting the large birds, but are simply watching them. This reflects how the Zulu admire and protect birds.

by Aditons (?)

Zulu culture

20th century

Gouache paint on watercolor paper, L. 30 cm x H. 23 cm x W. 1mm

BFPC collection #2012.44c

The traditional method for cooking meat in the Zulu culture is shown in this painting. While most traditional Zulu dishes are vegetarian, using maize, pumpkin, and squash, the Zulu do enjoy meat, and hunting. However, the Zulu consider large animals to be relatively sacred; cows are only butchered on special occasions like weddings and funerals, and hunts are carried out only a couple of times a month. As shown in the painting, the Zulu cook the entire animal over open flame, so they don’t waste any of the meat of these sacred animals. Once cooked, the meat is divided up by gender and age: The men eat the head, legs, and liver, and the women eat the tripe and ribs.

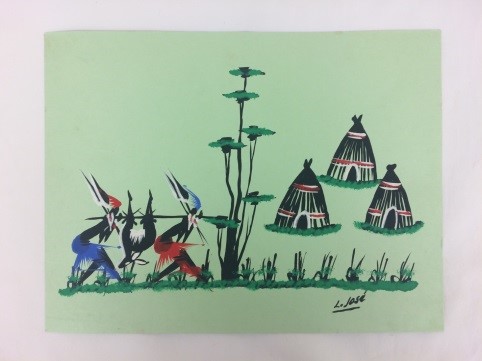

by L. José

Zulu culture

20th century

Gouache paint on watercolor paper, L. 30 cm x H. 23 cm x W. 1mm

BFPC collection #2012.44d

This painting illustrates a pair of hunters returning after a successful antelope hunt. In addition to wearing traditional clothing, these men carry a traditional small throwing spear called an iklwa. They are returning to a small village of traditional Zulu huts known as iqukwane, which are constructed of tree poles and adobe and thatched with native grasses. The doorway is positioned lower to the ground, so that when visitors enter they must bow, a sign of respect.

Haitian African Diaspora

Early 21st century

Oil paint on canvas, L. 10 cm x H. 38 cm x W. 2 cm

BFPC collection #2017.29

This Haitian African Diaspora painting depicts a scene from everyday life in Haiti; while it is oil on canvas, the style more closely resembles African gouache painting, with simplified figures as well as hatching and cross-hatching to create areas of shade and light. In this painting the characters are wearing their traditional clothing of long white shirts for men and white dresses for women, along with colorful headscarves. The baskets of goods carried on the women’s heads, the donkey laden with goods, the baskets in the foreground, and the chaotic crush of figures indicates that this is the scene of a traditional Haitian marketplace.

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu