With over 3,000 diverse ethnic groups spread over 54 countries, Africa offers a huge variety of traditions, customs, and forms of art. Among the most famous artworks produced on the continent are functional masks, which reflect the great importance of theater and masquerades in African education, ritual, and entertainment. Different forms of masks include face masks, body masks, and headdresses, and all of these serve as tools used to teach history, religion, and mythology; to remind people of traditions or enforce laws; and to honor distinguished community members and royalty. Masks take the form of people and animals as well as supernatural beings, and they may be naturalistic, stylized, or greatly abstracted. While masks most often represent the head, they sometimes represent another body part or they may incorporate the depiction of an entire person or creature.

An important consideration for understanding African masks is that, unlike how contemporary Western cultures usually see these objects in museums, in Africa a mask is not seen in isolation or as a single work of art on a pedestal, but as just one part of a costume that may completely cover the masquerader. In addition to the mask, the performer may wear rich cloth garments to emphasize grace and nobility, a netted body stocking that obscures the actor’s humanity, or a great mass of raffia fibers that shake and rustle with every stylized movement, suggesting a wild and supernatural creature. The masquerader may also hold rattles, bells, or props, and is often accompanied by additional percussion or music as well as by other actors in the story or ritual; all of these together create a complete aesthetic experience in the performance.

Makonde culture, Tanzania and Mozambique

20th century

Wood, pigment, plastic, synthetic rope, and cotton textile

L. 29 cm x W. 15 cm x H. 58 cm

Mace collection #TM064

While most masks are meant to cover the face or the entire head, this is not always the case with African masks, which may be worn on or over other parts of the body. This Makonde mask is a body mask meant to cover the torso. The body mask is used, along with a face mask and costume, for educational plays about fertility that form part of traditional rituals for the initiation of boys and girls into adult Makonde society. While the body mask quite clearly represents the torso of a nude, pregnant woman, this masquerade is danced by men, as masquerades are considered to be a male artform in Makonde culture.

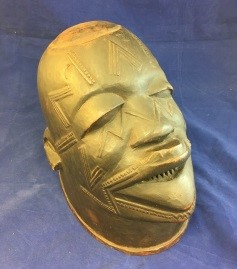

Makonde culture, Tanzania and Mozambique

20th century

Wood and pigment, L. 19 cm x W. 30 cm x H. 25 cm

Mace collection #TH048

Like the Fertility Body Mask, the Lipiko Helmet Mask is used in ceremonies that initiate children into adult Makonde society. The Lipiko character represents a mysterious, deceased man, and the Lipiko masquerader acts as a terrifying opponent whom the boys must fight and overpower in order to achieve adult status. The prominent, raised geometric designs on the face of this mask represent scarification, a traditional practice in Africa for beautification as well as to show status; the circular shape on the top of the mask was where fiber was once attached to represent hair. In addition to the full helmet mask, Lipiko masqueraders wear a full-body cloth costume with bells attached, and they undergo extensive training for the performances, which typically last half a day.

Ligbi culture, Côte D’Ivoire

20th century

Wood and pigment, L. 16.5 cm x W. 18 cm x H. 45 cm

Mace collection #TM008

This elongated mask is created for the Do Society of the Ligbi culture. The Do Society uses a wide variety of masks that portray characters varying from animals to distinguished community members. This Do mask has a large, beak-like feature that refers to the hornbill bird; while in many African cultures the hornbill refers to women’s power, among the Ligbi, the hornbill is a symbol of fertility and of the priority of family; the hornbill is also believed to attend to the souls of the deceased. Do Society masquerades encourage community bonding, and masks like these often appear at prestigious men’s funerals. While many Ligbi have converted to Islam, they continue to conduct traditional masquerades like these, also modifying their performances to enrich celebrations such as the dances associated with the end of Ramadan.

Bamana culture, Mali

20th century

Wood, metal, brass, and synthetic yarn

L. 18 cm x W. 18 cm x H. 78 cm

Mace collection #TM137

This mask portrays a female character, Dyoboli, and follows a strong tradition among African female masks in representing the ideal of female beauty for that culture, with an elongated, elegant face, a high forehead, and side tendrils of hair. Dyoboli is unusual, however, in that this character is also marred by physical and personality flaws. The antelope figure that sprouts from the top of her head represents a physical deformity on Dyoboli’s beauty that also reflects deformities of her character: Dyoboli is always late to the masquerade, she has too many suitors, and she is not submissive to men. Thus, although Dyoboli represents an ideal of beauty, this masquerade is used to remind women and girls how not to act in Bamana society and to reiterate that women should respect the morals of their traditional, patriarchal Bamana community.

Punu Lumbo culture, Gabon

20th century

Wood and pigment, L. 20 cm x W. 13 cm x H. 30 cm

Mace collection #TH030

While this face mask has lost much of its original white pigment, the remaining features identify it as the famous Okuyi Society face mask produced by the Punu sub-culture known as the Lumbo. These masks represent an important woman in the community who is now deceased, as indicated by her pale complexion and closed eyes. In addition to being covered in white pigment, the masks typically have heart-shaped faces, large eyes, full lips, and raised, diamond-shaped patterns of scarification on the forehead. The masks also have elaborately styled black hair, but this mask is unusual in incorporating two twin-like figures into its coiffure.

As with many cultures in Africa, masquerading is considered to be among the rights and responsibilities of men, and male actors wear these masks in performances at important funerals and during the initiations of young men into adult Lumbo society. The men take these duties very seriously, and if they perform the masquerade correctly, they are believed to transcend merely impersonating this character and to actually assume and act as the spirit during the masquerade.

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu