With over 3,000 diverse ethnic groups spread over 54 countries, Africa offers a huge variety of traditions, customs, and forms of art. Among the most famous artworks produced on the continent are functional masks, which reflect the great importance of theater and masquerades in African education, ritual, and entertainment. Different forms of masks include face masks, body masks, and headdresses, and all of these serve as tools used to teach history, religion, and mythology; to remind people of traditions or enforce laws; and to honor distinguished community members and royalty. Masks take the form of people and animals as well as supernatural beings, and they may be naturalistic, stylized, or greatly abstracted. While masks most often represent the head, they sometimes represent another body part or they may incorporate the depiction of an entire person or creature.

An important consideration for understanding African masks is that, unlike how contemporary Western cultures usually see these objects in museums, in Africa a mask is not seen in isolation or as a single work of art on a pedestal, but as just one part of a costume that may completely cover the masquerader. In addition to the mask, the performer may wear rich cloth garments to emphasize grace and nobility, a netted body stocking that obscures the actor’s humanity, or a great mass of raffia fibers that shake and rustle with every stylized movement, suggesting a wild and supernatural creature. The masquerader may also hold rattles, bells, or props, and is often accompanied by additional percussion or music as well as by other actors in the story or ritual; all of these together create a complete aesthetic experience in the performance.

Igala culture, Nigeria

20th century

Wood and pigment, L. 22 cm x W. 19 cm x H. 34 cm

Mace collection #TH021

The masks of the Igala culture generally represent high-status ancestors, both individual ancestors and the ancestors as a whole. Among the Igala is a high-status group known as the Orata clan, who are very proud of their ancestors known as the Akpoto. The Orata produce helmet masks known as odumado, which represent the Akpoto; they take special care of these masks and serve as performers of the masks in public masquerades as well as during the Ocho Festival, the annual harvest of new yams. The Ocho Festival is a very important celebration for the Igala, as during this event, land rights are re-established, the soil is cleansed, and social and political connections can be made or re-established among the different classes. The odumado masks are performed during the beginning of the Ocho Festival in a masquerade that honors the Akpoto, the original owners of the land.

Baule culture, Côte D’Ivoire

20th century

Wood, pigment, L. 19.5 cm x W. 12 cm x H. 94 cm

Mace collection #TM032

The Baule nda, or double-face mask, is made to honor a highly admired and honorable male or female member of the community. The two faces of the mask represent the duality between the reality of that member of the community and the artistic representation of that person. Nda masks are an important part of Baule masquerades that are performed as public entertainment and also as part of funerals for important female community members. The Double Face Mask (Nda) with Female Figure is unusual because of the full figure of a woman that stands on the top of the mask. This figure possibly represents a female ancestor, which emphasizes the importance of senior female members of the community.

Bamileke culture, Cameroon

20th century

Wood, pigment, L. 31 cm x W. 14 cm x H. 84 cm

Mace collection #TM065

The buffalo mask is one of two prominent zoomorphic masks produced by the Bamileke culture, the other being the elephant mask. These masks are owned and worn by the fon, the Bamileke king, and they represent the power and strength of the king; they also symbolize how fons are believed to possess the supernatural ability to actually change into these animals. The masks are danced in order to encourage a successful hunt or harvest and in celebrations held during the dry season. Expertly crafted buffalo and elephant masks elevate the status of the fon as well as the status of the artist who created them.

Marka culture, Mali

20th century

Wood, leather, hair, and brass, L. 31 cm x W. 14 cm x H. 84 cm

Mace collection #TM138

This Dyoboli koun mask is a specific variety of a mask made by the Marka culture’s N’tomo society. As also noted in the display of the Seven Ebony Maskettes in this exhibit, the Marka are a sub-culture of the Bamana, and Marka N’tomo masks therefore have strongly similar shapes and meanings as masks produced by the N’tomo society of the Bamana; they differ, however, in details such as the number of horns and the addition of brass sheeting to the surface of the masks. The Dyoboli koun mask is used in Marka N’tomo society circumcision ceremonies that take place during the initiation of boys into adulthood, as well as in masquerades in which Marka men are elevated to a higher rank in social status.

The Marka Dyoboli mask also incorporates a depiction of the character Dyoboli. As described in the display of Dyoboli Mask with Antelope Head and Brass Repoussé, Dyoboli is a beautiful woman who is uncouth, always late, seen as undependable, and used as an example to teach young men of how appearances can be deceiving–as well as an example to teach young women about how not to act.

by L. J.

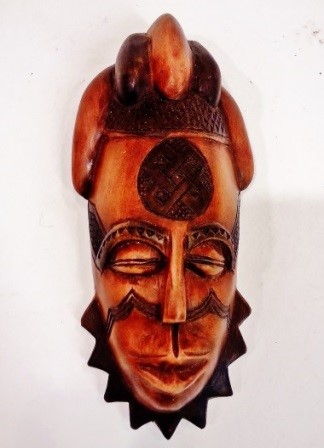

Kinshasa, Zaire

21st century

Wood and pigment, L. 8.7 cm x W. 5.8 cm x H. 19.7 cm

BFPC collection #2009.02a

This contemporary mask was created in Kinsasha, Zaire for the tourist trade by an artist known as L. J. Although this is not a traditional mask and was not created for masquerades, L. J. clearly took inspiration from traditional cultures neighboring the city of Kinsasha, most likely the Chokwe culture to the south and the Punu culture to the northwest. Like the contemporary mask, traditional Chokwe Pwo masks have large, lemon-shaped, closed eyes as well as an interlaced scarification design on the forehead, and they also often have curving cheek scarification. Punu masks, as exemplified by the Lumbo sub-culture mask in this exhibit, also have lemon-shaped, closed eyes, forehead scarification, and scarification on the temples, as well as elaborate hairstyles with multiple rounded lobes; thus, they also likely served as a model for L. J.’s contemporary mask.

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu