Justin Sissel and Dr. Mike Burton walked through a golden field on a clear blue autumn day.

“Look at this crop of beans,” Burton said. “They are chest-high!”

It was October 2017 at the Kindrick Family Farm at Missouri State University, a parcel of land south of the Springfield-Branson National Airport.

The land was given to the William H. Darr College of Agriculture in spring 2017 by the Rev. Dr. Paula Kindrick Hartsfield, a 1976 alumna, and her husband, George.

“What is most important to me about the gift is that forever it will be known as the Kindrick Family Farm. I have a lot of love and respect for my family, and so that’s very important to me.”

Burton, a professor in the environmental plant science and natural resources department, and Sissel, the farm operations manager, were admiring a crop that had been planted in early summer.

“I am so tickled. For this area, and for our first time on this land, this is a heck of a crop.”

This gift means that, for the first time, MSU’s College of Agriculture has land dedicated to row crops. This fills a huge need for the college.

Sissel is an ’04 alumnus with a bachelor’s degree in animal science. Though he has worked in MSU agriculture for more than 10 years, he said the farm “has been a learning experience for everyone, even me.”

There have been hands-on opportunities for all involved.

In fact, he said, “most of the planting and spraying work was done by students.”

Sissel and Burton predicted that the results of the first harvest would be good because the land had fertile soil, and rain had been on their side last summer. A large harvest means a profit — and that’s money that can be reinvested in Missouri State, the College of Agriculture and the Kindrick Family Farm.

So, how good was the harvest?

On Dec. 14, 2017, it was time to find out.

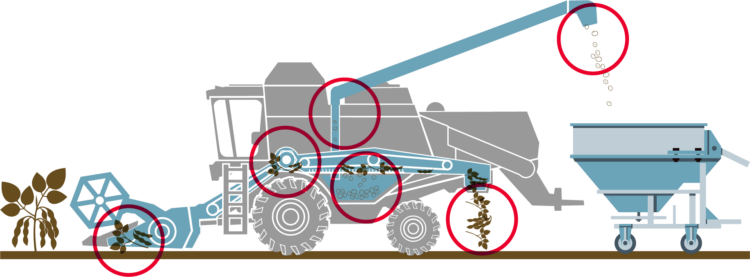

A Gleaner R7 combine harvester rumbled in the field. MSU hired an independent contractor to run it, since the university doesn’t own a combine.

A group of faculty, alumni, graduate students and undergraduate students were gathered to witness the university’s first-ever soybean harvest at the Kindrick Family Farm.

“We’re getting along pretty well,” Burton said as soybeans were transferred from the combine into a “weigh wagon.”

The scale on this machine helped the team determine their yield per acre.

MSU students were gathered around the wagon.

“We’re taking samples for weight, and looking to see if there are any pink or purple spots,” said Jordan Gott, a graduate student in agriculture. Pink or purple spots could indicate disease.

“But black spots are normal and indicate maturity,” said Scott McElveen, also a graduate student.

So far, all the varieties were looking good.

A few minutes later, Burton took Gott, McElveen and fellow graduate student Chris Groh into a part of the field that had already been harvested.

Burton wanted them to take soil samples to see if MSU would need to “amend” the soil with lime or fertilizer in anticipation of the next crop. Soil amendments help improve plant growth and health.

“Go straight into the ground,” Burton said to Gott as she was stomping on a “footstep probe soil sampler,” a cylindrical metal tool with a hollow middle.

How it works: You shove the probe into the ground by stepping on it, and the hollow core fills with soil. The students would need to get pretty far into the ground to get enough soil.

For Gott, this wasn’t just an academic exercise. Her career goal is to help people in developing nations sustain their land for food production. Her time spent learning how to sample soil may someday translate to a better world.

Groh, who is in the master’s in plant science program, is also interested in international agriculture development, and has been to Europe and Turkey.

His review of the farm: “It’s a great place to apply what we have learned in class. Now, we get to be out here and actually do it.”

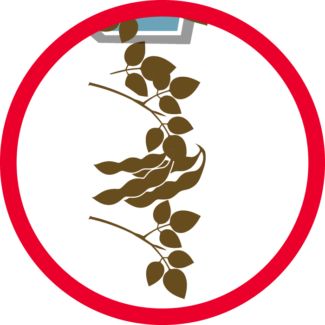

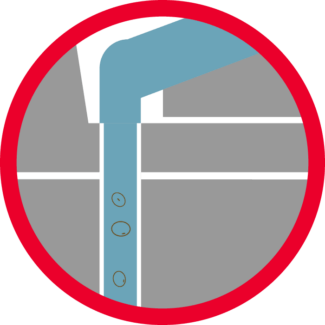

How soybeans are harvested

First harvest results in good yield

“The beans are high in protein and can be used to supplement protein in animal feed or our food.”

When all the soybeans were taken out of the field, they were transported to a grain-holding facility.

They were sold to a local exchange, a commodities broker for agriculture products.

They may become soy oil or soy meal.

In late October, Burton’s undergraduate students had estimated the farm would produce about 70 bushels of beans per acre.

“That was a bit optimistic! I ended up questioning the students about how their estimates would be biased if they selected ‘big’ plants rather than ‘random’ plants.”

After the December harvest, they actually ranged from about 60 to 65 bushels per acre. Any gross income from this good yield would be reinvested in the College of Agriculture.

The Kindrick Family Farm by the numbers

What is on the land?

Now, it’s spring.

Sissel and Burton will be walking in green fields, not golden, at this time of year.

All of the grain crops they plant at the farm are annuals. That means they’ll reseed each year. They planned to put soybeans on most of the farm again in 2018. After that, their options are open.

They will rotate crops to keep the land healthy and provide diverse educational and research opportunities.

“We could do corn in the future,” Burton said. “We could possibly put in wheat, or we may plant oat, canola, sorghum or rye.”

He’s excited to make plans for the Kindrick Family Farm.

“It’s an amazing gift that allows us to do things we could not before, on a scale we could not imagine before.”

“When I was in school, we had the Darr Center and part of Bakers Acres. Now, all told, the College of Agriculture has about 4,000 acres in five counties. We cover a lot things.”

History of the land

The farm given by the Rev. Dr. Paula Kindrick Hartsfield has been in her family since 1876.

Her great-great-grandparents, Samuel and Stella Wilson, came from Sweet Water, Tennessee, to Greene County, Missouri, in an ox cart.

“Their daughter, Elizabeth, was in that cart, and she was my dad’s grandmother.”

The Wilsons bought 80 acres from the A&P Railroad and built a log cabin on the property. The current house on the property was built around that cabin.

Educational philanthropy must run in the family: At some point, the Wilsons gave one acre of their 80 acres so that a one-room schoolhouse, called Center School, could be situated on the property.

“When schools were consolidated, that acre must have been given back to the original owner,” Kindrick Hartsfield said.

The entrance to the Wilsons’ farm was called “the seven-mile corner” because it was seven miles to the Springfield square. Their land was along a road popular for travel.

“You know what that became? Route 66. My dad remembered Route 66 being paved.”

Eventually, the farm passed to Kindrick Hartsfield’s grandfather. Paula lived nearby and visited the land regularly as a child and teen.

“I would work in the summers out in the fields. I would rake and bale hay. When I drove the tractor for raking hay, I felt a particular closeness to God. I’d also drive the tractor pulling a flat-bed wagon, and we’d pick up rocks. My family used to joke that the land grew rocks because it always seemed that there were rocks replacing the ones we picked up!”

After her grandfather passed away, her dad, Clarence Mitchell “Buzz” Kindrick, and his two brothers, Robert Lee “Bob” and William “Bill” Kindrick, were partners on that farm.

A fond memory for Kindrick Hartsfield: When her dad was farming there, her mom, Hilda Kindrick, would take him a large home-cooked mid-day meal for an influx of calories.

“She’d put it in a rectangular, covered cake pan. She’d have different vegetables, meat, bread and everything in there. We’d drive it right to my dad so he didn’t have to take much time out of his day.”

Kindrick Hartsfield is an only child, and her two uncles did not marry. The property passed to her. Since she lives in Jefferson City, Missouri, she leased it to farmers.

“They were doing a good job farming the tillable land, but fence rows had become overgrown and the land didn’t look like it did when my family was actively farming it. We wanted a more permanent owner.”

“My family always had a lot of pride in their property, so one of the conditions of the gift was that the fence rows along the roadway be cleared. This allows the pretty crops to be seen, as they were in days past.”

Her husband, George, had the idea of giving it to Missouri State.

She said giving the farm has been an affirming process.

“It has been rewarding to get to know the faculty and the administration, and to feel their genuine appreciativeness. Knowing how the students will benefit from it, I think my parents and uncles would be very pleased we’ve done this. That was what was important to me.”

Ag facilities continue to grow

The number of facilities operated by the MSU College of Agriculture continues to expand. A few examples:

- Journagan Ranch: 3,300-acre working cattle ranch 60 miles from Springfield; has one of the largest herds of Polled Herefords in the United States

- Fruit Experiment Station: On the Mountain Grove campus; dedicated to the advancement and improvement of fruit crops in Missouri

- Darr Agricultural Center: Facility in Springfield with 90 acres of land, the Bond Learning Center and Pinegar Arena

- Bakers Acres: Property near Marshfield, home to cattle; shares space with MSU’s William G. and Retha Stone Baker Observatory

- Shealy Farm: 250 acres near Fair Grove, Missouri, with livestock and buildings

- The Woodlands: 161 acres of timber land southeast of Ritter Springs Park in Springfield; used as an outdoor nature laboratory

Meet the alumna behind the gift

Paula Kindrick Hartsfield used three words over and over during our talk: Serve. Service. Servant.

She’s spent most of her life trying to be of assistance to others.

Growing up on an Ozarks farm

Kindrick Hartsfield did not grow up on the farm she gave to MSU. She lived on 240 acres nearby and attended schools in Willard.

“When I was planning my senior schedule, I was trying to think about what I wanted to do with my life.”

She wanted to teach and to do the most good for the largest number of students. She decided on vocational home economics.

“When I was a senior in high school, our 240-acre farm took a direct hit from a tornado. It destroyed our farm buildings and damaged equipment. I was an only child and I didn’t want my parents to have financial difficulty sending me to school. I had scholarships for MSU, and I drove back and forth from home. That’s how I chose MSU, and I’ve never regretted it.”

Starting a career in the classroom

On campus, she was active in groups related to home economics (an academics area now called family and consumer sciences education).

After earning her bachelor’s degree at Missouri State in 1976, she earned a master’s from Kansas State University in 1978.

Her first teaching job was in Monett, Missouri. During that time, one of her students was elected a national officer of Future Homemakers of America, or FHA, now called Family, Career and Community Leaders of America. Kindrick Hartsfield was elected to the organization’s national board of directors.

But something a career planner had once told her was about to come true.

“He said, ‘You won’t stay in the classroom long. You’ll be an administrator.’ I thought, ‘No. I want to teach.’ I taught for just two years, and then I went into administration. He was smarter than I gave him credit for!”

Improving education for all Missourians

In 1979, Kindrick Hartsfield was recruited to work in Jefferson City. She joined the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education as a state supervisor of home economics education and the state advisor of then-FHA.

By 1983, she had been promoted to state director of home economics education. She worked to improve home economics education for all Missourians.

“I started a foundation that allowed us to do some things for our students and teachers that we would not have been able to do with just federal and state funds or student dues. We had money for leadership training programs for our Future Homemakers of America state officers. We were able to bring in some big-name speakers for teachers during the Missouri Vocational Association annual conference. It was a good feeling to get that foundation started.”

Helping at-risk, middle class students

In 1988, she started working for the Jefferson City School District as the assistant director of Nichols Career Center. The center offers career and technical programs that prepare students for the workforce, military or technical colleges after high school.

“My vocational students, many times, hadn’t been traditionally good students. But when they get into a technical program that is their love, they can do things you and I cannot do. We need those skills. We need people to perform them well. It’s so wonderful to see the light come on and for them to feel valued.”

In 1991, she earned a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Missouri.

She served in many district leadership roles. Among her major accomplishments:

- Initiating programming for at-risk students.

- Serving as the A+ School Coordinator. The A+ Scholarship Program pays high school students’ tuition to any Missouri public community college, vocational or technical school. She wrote an A+ Schools grant application the first year the program was available. “Jefferson City became one of the first districts to have the A+ grant. That was good for our students because I saw it as financial help for the middle class.”

- Assuming the role of director of planning when the position was created in 1997. She helped set curriculum standards and create goals for the district.

- Obtaining grants to help homeless students.

She was with the district until 2008, when she retired from education.

Working with the homeless

In 2012, Kindrick Hartsfield was ordained as an Episcopal deacon.

“It’s a servant-ministry position,” she said. “A deacon is to be a bridge between the church and the world. I’m supposed to bring the cares of the world to the church, and then get the church to go out beyond its walls.”

Her focus areas include poverty and social justice.

“Jesus talked a lot about not forgetting the poor.”

Her church is involved in running a nondenominational community building. It is growing into a nonprofit called Common Ground. She works with homeless families there, pointing them to programs and resources to help them become self-sufficient.

‘We’ve been able to do well and contribute’

She and her husband, George, live in Jefferson City, Missouri. They’ve been married since 1982.

They both appreciate public higher education and share a passion for public service. He served as Jefferson City’s mayor for eight years starting in 1979, and was on the City Council for two years before that.

“We certainly didn’t come from wealth. I came from a hard-working, Christian, saving, dairy-farming family. With the educations my husband and I received from public institutions, we’ve been able to do well and contribute to society in important professions and vocations. It’s provided a good life.”

This is not the only gift to MSU from her family

Other gifts established by the Rev. Dr. Paula Kindrick Hartsfield and George Hartsfield:

- Robert Lee “Bob” Kindrick Agricultural Industry Study Fund: This fund, established through a deferred-gift provision, is in the name of one of her uncles.

- Robert Lee “Bob” Kindrick Outstanding Student Award for Agricultural Industry Study

- Rev. Dr. Paula Kindrick Hartsfield Family and Consumer Science Education Scholarship: Awarded annually to a full-time student majoring in family and consumer sciences education.

Great vision by Dr. Paula Kindrick Hartsfield. True visionary. Selfless efforts.

Serve. Service. Servant

If everyone follows this principle the world will be full of joy and happiness.