The Florida Herpetology Conference saw some familiar faces. Kristen Sardina and Ethan Hollender, both from Missouri State biology, set out for adventure.

Hollender presented on his research on turtle communities at mined lands and natural oxbow lakes in Kansas.

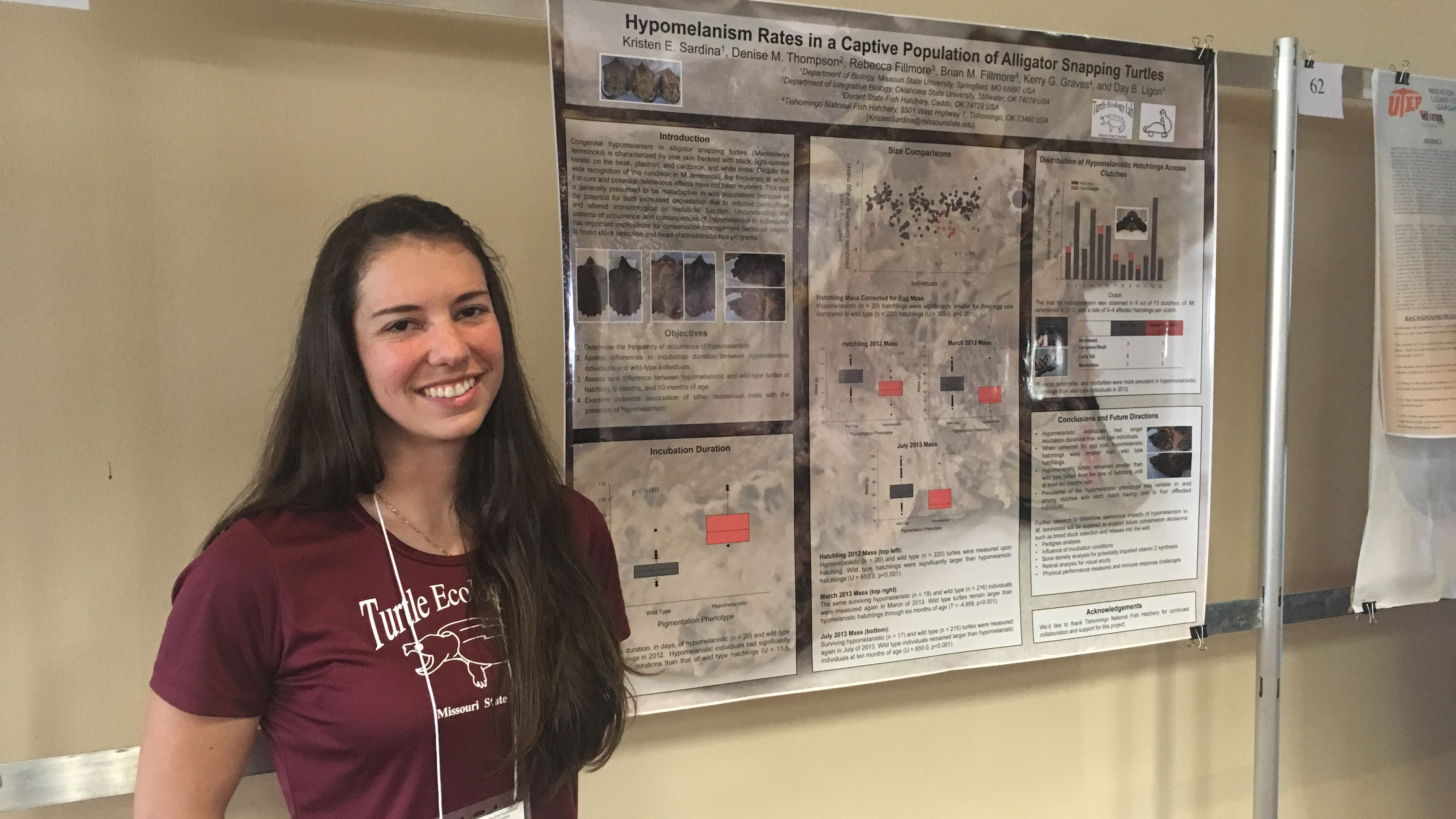

Sardina presented her research as well and won runner up in the Best Student Poster category.

The conference was in Gainesville, Florida, March 24-25.

Sardina and Hollender couldn’t stay away from nature for long. They camped at Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park during the conference.

“Our Florida trip would not have been complete without encountering at least a few Anolis lizards and one displeased American alligator,” Sardina said.

About Sardina’s research

Sardina’s research focuses on turtles. Specifically, she looks for why some alligator snapping turtles have hypomelanism. Hypomelanism is a congenital trait that reduces pigmentation in skin.

Alligator snapping turtles usually have a brown pigmentation. When they have this trait, their skin is pink with freckles, have white irises and light-colored keratin on their beak, carapace and plastron.

Sardina did her study at Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery in Oklahoma under the advisement — or shell — of Dr. Day Ligon, associate professor of biology. They have no hypomelanistic brood stock, yet there are turtles with those traits.

Sardina found that the hypomelanistic turtles took longer for their eggs to incubate and were smaller when hatched. Even over a 10 month period, these turtles did nto catch up to the size of their wild-type counterparts.

These turtles have the odds against them, as her research observed that they were 20 percent more likely to have deformities. They were also 13 percent more likely to die.

Sardina, who affectionally calls these turtles “pinkies” (along with the hatchery staff and researchers), knew she wanted to study them as soon as she saw them. She got the chance a year after she saw them.

“Many conservation concerns in Florida are very different from ours in the Midwest — primarily due to the unique ecosystems and innundation of invasive species in Florida— but we still have many of the same overarching goals to successfully manage native wildlife,” said Sardina.

“The crowd at the conference was incredibly welcoming and supportive, so it was the perfect environment to present my poster and give my first oral presentation. I received a lot of insightful input on my presentations and made several new connections. I am also a native Floridian, so it was great to see some familiar faces from the past,” Sardina added.

Sardina has taken this research to three different conferences and has had a lot of interest each time. She’s glad this is happening, because she hopes others can build off her research.

She hopes someday to know why the juvenile “pinkies” are often either half or nearly double the size of their regularly pigmented counterparts.

“These pink turtles have rightfully earned their position as our unrelenting outliers,” Sardina said.