Everyone remembers the scene from the film “National Treasure” when Ben Gates has to break into the National Archives to steal the Declaration of Independence. And who can forget the scene in “Angels and Demons” when Robert Langdon must escape the Vatican archives after being trapped while reviewing classified manuscripts? These Hollywood scenes have painted a picture of what it means to be a historian, humanitarian, and even an English major. It’s traveling halfway across the world just to catch a glimpse of an old document. However, those days are behind us, as digital humanities adapts research to a more technologically advanced world.

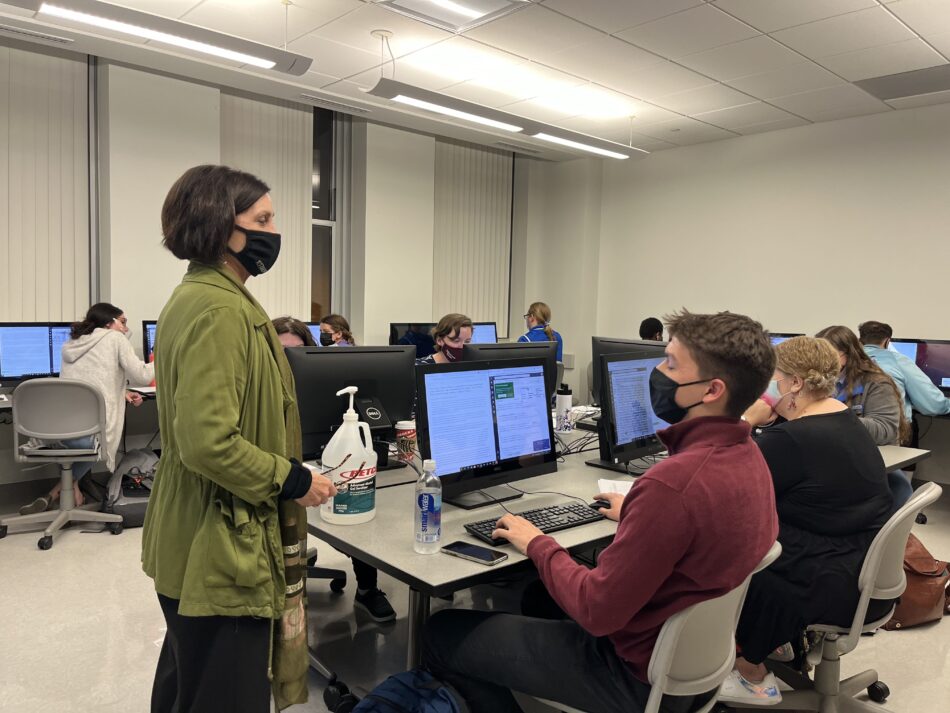

In the fall of 2021, Dr. Etta Madden, Assistant Department Head of English, offered the annual Research Methods course. But this year, of the 16-week class, four weeks were devoted to transcribing the texts of Anne Hampton Brewster, a 19th-century American journalist.

Although transcribing Brewster’s texts might not be as adrenaline-pumped as stealing a historical document or sneaking around the Vatican, her news accounts document a fraught period of political upheaval in Italy during the late 1800s, specifically 1869 to 1870. At the time, the Italian peninsula was undergoing unification to become the Kingdom of Italy. This meant that all eyes, including Catholics in the U.S., were on the Pope and King Victor Emmanuel II with the question, “Is the Pope going to remain in charge of Rome?” Brewster, who had been a writer for many years in the U.S., sent correspondence to Philadelphia and Boston newspapers.

In addition to writing about the edgy angles of politics, Brewster provided a perspective of the art and culture of Italy at the time. Her articles focused on who was in Rome, be they Italian, American, or anything in between. The journalist grew up as an elite and educated Philadelphian and, by age 50, had learned that to keep up in a writer’s world, she helped to create the news.

“She’s much like today’s influencers on social media. She was dropping names of who’s in Rome, who she’s seeing, who she’s having dinner with, and they want to see their names in the paper. The publishers want to sell newspapers, so Brewster becomes part of the wheel of this feed,” Madden explained.

When she wasn’t writing, she was networking. She lived in a fourteen-room apartment in a neighborhood in Rome where many political leaders lived, and she was known for hosting two receptions a week. Such events helped Brewster gather her stories. She name-dropped, wrote about art and culture, and ingratiated herself into the high society of Italy. These social gatherings made her indispensable.

Unfortunately, much of Brewster’s newspaper work is inaccessible to the public. This is where digital humanities can help.

The phrase “digital humanities” surfaced around the year 2000. Originally, it encompassed anything using or related to computers and the conservation of literature history. Nowadays, it encompasses when literary studies goes beyond a printed book or article. This includes not only accessing documents online but also tapping into special collections at renowned facilities like Yale or Oxford archives, or the Library Company of Philadelphia, which houses much of Brewster’s writings.

“It’s really about making art and literature that used to be available to only the privileged available to a much larger public,” Madden said.

Research used to mean opening a book, reading it, and writing a traditional analysis. As the future of research methods is changing, however, Madden is determined to position her students ahead of the curve. She is eager to help her students realize the value of digital humanities and the cutting-edge advantage it can give them in the job market.

“My goal has been to recover little-known women and what we can learn from them.” —Dr. Etta Madden

Madden has launched the Anne Hampton Brewster Recovery Hub Project, in collaboration with Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and the University of Nebraska and with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Her team is already equipped with two former Missouri State graduate students, Natalie Whitaker, ’14, and Alyssah Morrison, ’21. Additionally, all the graduate students who participated in the Research Methods class will be credited on the project website. And this is only the beginning. With funding from MSU’s Graduate College, Madden is working with two more students this semester, Grace Willis, ’22, and Makenna Cornelison, ’22.

While it may be a while before a summer blockbuster is released, documenting the impact Brewster and other women writers have had on the field of journalism, digital humanities is bringing us one step closer by making their work more accessible to the public.