Archive for August, 2013

Seeking treatment for brain’s ‘perfect storm’

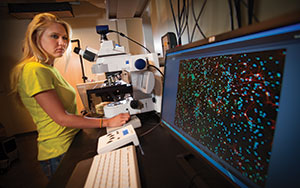

Brittany Thurman, a biology major, uses a fluorescent microscopy to study how new drugs being developed to treat neurological diseases control cellular activity.

A perfect storm: It can erupt at any time if a variety of factors interact just right. Maybe it all starts with a stressful day at work. Although you’re relieved to go home and get work off your mind, you can’t, leaving you with a fitful night of sleep. When you wake, you have a kink in your neck. The morning rolls on, and you juggle your schedule as well as the needs of your household. You step onto an elevator — part of your normal routine — and you take a whiff of strong perfume. Your sinuses are stimulated, and you undergo a migraine attack.

In the world of Dr. Paul Durham, professor of cell biology at Missouri State University and director of the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, that is the “perfect storm” model. In this model, each factor plays a role in making the nerves more hyperactive and sensitive, until one of them tips the balance.

“These nerves begin to do their job a little too well,” Durham said. “Instead of responding to a stimulus in a normal way and alerting you about it, the nervous system response becomes not physiological, but pathological.”

In the early 1990s, during his postdoctoral work at the University of Iowa, Durham became interested in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) — a protein made in nerve cells and known to promote inflammation. As a cell biologist, he was intrigued that increased CGRP levels were correlated with the pain intensity of a migraine attack. Twenty years later, he is an international expert on the study of the trigeminal nerve and orofacial pain.

The trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the head and face, so Durham studies the biological basis for migraines, headaches, temporomandibular joint (or TMJ) pain, jaw pain, toothaches, gum pain, sinus headaches and rhinosinusitis, among others.

His work could have tremendous impact, as studies have shown that approximately 36 million Americans suffer from migraines.

Studying causes of pain, ways to treat it

Graduate chemistry student Geoffrey Manani uses techniques called high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and gas

chromatography mass spectrometry to identify compounds in plant and animal material that suppress inflammation and promote healthy cell activity.

In his lab at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, known as JVIC, Durham researches why nerve cells become hyperactive and why they cause pain. Nerve cells are grown in culture dishes, allowing him and his fellow researchers to see how cells react with various drugs.

During the past couple of years, his research team took their quest for answers one step further: How and why does pain move from acute pain to chronic pain?

“What we’re finding with chronic pain patients is they get themselves in a vicious cycle,” Durham said. “Once they start having pain, they usually don’t sleep as well, which usually causes them more pain. Then they begin to stress about it, and then they get depressed about that. All of these things keep snowballing. Pretty soon you have a system that is out of balance.”

Partially due to his involvement with organizations such as the Society for Neuroscience, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Headache Society, Inflammation Research Association, American Academy of Orofacial Pain and the American Pain Society, pharmaceutical companies often enlist his help in determining the viability and effectiveness of their products. Since JVIC opened in 2007, Durham has been awarded more than $9 million in grants, including funding from pharmaceutical companies and government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health.

“The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results.” — Evan Clark, student

Students of all ages can assist in research

Durham’s laboratory is involved in the identification and characterization of bacteria obtained from medical tissues as well as food products.

As you tour the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences, or CBLS, at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, you may notice how young everyone appears. The approximately 20 researchers in the lab are a mix of full-time employees, undergraduate and graduate students — all homegrown from Missouri State University, Durham noted. Durham holds the only PhD degree in the lab.

“I’ve never looked at undergrads as being any different than grad students,” he said. “If someone is passionate about science and learning, and we put them in the right environment, then they just take off.”

Evan Clark, a senior who has worked in Durham’s lab since 2011, said the CBLS lab has taught him about the design and set-up of medical clinical trials, the importance of teamwork and organization, and the procedures and protocols of research.

Junior biology major Andrew Miller prepares samples for bacterial analysis.

Clark led a menstrual-related migraine study: “The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results,” Clark said. “I am truly appreciative of the opportunity Dr. Durham has given me. His support has made me a better student and person.”

In the last 10 years, Durham has supervised the research of more than 75 students in the CBLS, and says this is one of the best parts of his job: “The students have played a key role in everything we’ve been able to do.”

In the lab, at home, in the classroom or in his downtime, Durham lives to help people — especially youth. As an example, one of his current studies may help eliminate children’s fears of needles.

Instead of using blood as a diagnostic indicator, Durham has studied the effectiveness of using human saliva to look for protein levels, discern what each protein indicates and understand the progression of diseases. Now he’s researching the saliva of a group of neonatal babies and pediatric oncology patients in Utah, planning to develop a diagnostic tool to measure biomarkers in saliva that hospitals and doctors could use instead of drawing blood from children.

JVIC: great resources, collaborations

Jordan Valley Innovation Center, a former milling facility, is a seven-story state-of-the-art research and innovation accelerator. When it opened in 2007, it became the home of CBLS, staying true to its commitment to the development and support of advanced biotechnology industries in Missouri.

Human cancer cells, which can be stored for years in liquid nitrogen, are often used in Durham’s research since they mimic normal human cells.

JVIC is also home to corporate affiliates in the medical, technology and defense industries and the Center for Applied Science and Engineering of Missouri State.

“We have the full complement of all the techniques and equipment that we need in one building, which is really unique,” Durham said. “Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.”

In addition to equipment, Durham said the ability to collaborate with scientists with other expertise has been a huge advantage of being housed at JVIC. One prime example was the development of a “smart” bandage that delivers a drug to promote healthy wound healing.

Starting with a tent material that would decontaminate biological and chemical warfare agents — a product that was developed at JVIC as well — Durham and others at JVIC collaborated through several stages of development. And it was a success.

“It took electroactive polymer chemists to figure out how to put the matrix together, but then you had to have material science people working on how to make a bandage that didn’t stick to the wound. Then you needed electrical current going to the bandage, so you had to have someone who could build an electric device that delivered the right amount of current,” he said. “With the help of Crosslink, an affiliate of JVIC, we were actually able to work with their scientists to develop the product and have it release the drugs that we wanted into the wound to promote healing. We all worked together as a team to make it happen.”

“Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.” — Dr. Paul Durham

Empowering people to prevent disease

The worldwide scientific community collaborated to complete the Human Genome Project in 2003, sequencing the chemical base pairs of DNA to determine the significance of each gene. Since then, research has shown that the average person has 10 genes predisposing him or her to a major disease. Keeping that illness from becoming a reality is another area of research interest for Durham.

Joshua Haydon, junior research scientist, prepares cancer cells to study the effect of a nutraceutical product on inflammatory pathways known to promote disease progression.

“Why are they still healthy? What it comes down to is diet, exercise, good environment and healthy sleep patterns,” he said.

On top of the DNA structure (the genome) is another similar structure called the epigenome, Durham explained. The epigenome, which is responsible for how DNA is packaged and controlling what genes are turned on or off in a cell, can be manipulated through diet, exercise and sleep.

“For example, if you have a ‘bad’ gene that increases the likelihood for a disease, you could completely turn it off for most of your lifetime through epigenetic changes.”

It’s a powerful thing — empowering patients with the knowledge that they have control over a disease. Durham sees nutraceuticals, compounds found naturally in fruits, vegetables and plants, as an emerging field in the next 10 years. These nutraceuticals will be key in a lifestyle plan to keep the epigenome from manifesting certain illnesses.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

“Five or six years ago, we started looking at cocoa and wondered what would happen if you incorporated more dark chocolate in your diet. Would that actually protect you against certain pain pathways? When you incorporate dark chocolate into your diet, you are basically quieting pain-conducting nerve cells. The cocoa modulates a healthy response toward inflammatory and painful events. So the cocoa actually blunts the perfect storm that’s developing.”

Migraine sufferers take heart — clearer days are ahead. Durham and his team of researchers are working to find relief for this debilitating affliction.

Student examines effect of new pesticide on mussels

“Dr. Barnhart can be considered the godfather of mussel-rearing,” Pletta said.

Pletta worked for a year and a half in Minnesota on a field-survey team studying mussels in the Mississippi River, then graduate school beckoned. The opportunity to work with someone like Barnhart drew her to Missouri State.

Students see full life cycle of mussels

Dr. Chris Barnhart, biology professor, and Madeline Pletta examine mussel shells from the Meramec River, which has roughly 40 native species of freshwater mussels.

The Missouri State lab is a captive-propagation facility, which means mussels live there and are bred in a controlled environment.

Pletta gained hands-on lab experience and led research projects on a variety of mussels, including the federally endangered pink mucket and invasive species such as the zebra mussel.

Freshwater mussels start life as larvae: tiny, temporary parasites that live on the gills of fish. These are captured in the lab on fine screens after they drop off the fish. Several hundred nearly microscopic juvenile mussels can be obtained per fish.

These juveniles grow to the size of several centimeters in the MSU facility. Barnhart also has a mussel-culture facility at the Kansas City Zoo, and the animals grow to a larger size there. These mussels are used for toxicology research, as well as restoration of endangered species.

“Mussels from the size of a pinhead to the size of your fist are raised at Missouri State and at the Kansas City Zoo,” Pletta said.

Student’s thesis may help native mussels

Barnhart’s lab was approached by Marrone Bio Innovations, a green pesticide company, to test the effect of its new molluscicide (a pesticide that kills mollusks) on native mussels. The molluscicide, Zequanox, is used to control the zebra mussel, a non-native species that is a pest in many parts of the world. This project became part of Pletta’s thesis research, so she could ensure Zequanox does not harm native mussel species.

Mussels benefit the ecosystem because they filter water as they feed. However, the invasive zebra mussel is hazardous since it can adhere to anything. One example Pletta noted was the ability of zebra mussels to clog pipes carrying cooling water in power plants.

Madeline Pletta and Dr. Chris Barnhart look at largemouth bass kept in tanks in MSU’s Temple Hall. Barnhart and his students inoculate these fish with mussel larvae, since mussels initially develop as parasites on fish gills. The larvae eventually fall off and are raised at Missouri State and the Kansas City Zoo.

The first stage of her research involved testing toxicity of Zequanox on four species of native mussels, including the endangered pink mucket. The tests showed Zequanox has very little effect on the native species, indicating it is a promising product. Then she expanded her research to include seven species, researching their ability to capture different sizes of food particles.

Using a highly sensitive particle counter, Pletta released polystyrene microbeads along with food into tanks of mollusks and tested the water at specific increments. As she watched, waited and tested, she found some surprising results.

“The overwhelming knowledge and literature out there says zebra mussels are excellent at clearing small particles and that native mussels aren’t. Realistically, what I’ve seen is that natives are as efficient, or more efficient, than zebra mussels at capturing the smallest particles when you’re taking the body size into account.”

Ultimately, her findings will be instrumental in determining the appropriate particle size and concentration for Zequanox, as well as allowing Marrone Bio Innovations to get Environmental Protection Agency approval for open-water use of their product.

Did you hear? Students offer free screenings

Dr. Wafaa Kaf, a professor of audiology from Al Sharqia, Egypt, has spent many of her 10 years at Missouri State researching ways to evaluate the hearing of these challenging populations.

Kaf is most interested in detecting mild degrees of hearing loss using “electrophysiological measures” — ways to assess hearing that don’t rely on patient response, but instead objectively track the brain’s responses to sounds. She may use electrodes placed on a patient’s head or probes inserted into a patient’s ear.

Why hearing screenings matter

Luke Wilson, 3, is given a hearing screening by Dr. Wafaa Kaf. The electrodes measure his brain’s responses to sounds.

Kaf said hearing loss is a substantial problem that is largely hidden, and estimates that there are 35 million American children and adults with mild, moderate or severe hearing loss. They may experience no symptoms, or just have slight ear pain or an ear infection that resolves quickly.

However, hearing damage lasts forever.

“Hearing is one of the most important things for children because it is the precursor for them to develop the ability to talk,” Kaf said. Hearing loss may lead to stunted speech-language development, making these children feel less competent and confident when they reach school.

These students may be held back academically and socially due to a problem they cannot control and may not even know about.

Addressing the community problem

Kaf started a service-learning pediatric audiology class for doctoral students in 2005. With her supervision, students perform free hearing and middle-ear screenings for low-income and underserved populations. Since the start of the class, she and her students have screened more than 400 children in the Ozarks.

The audiology students take portable equipment to community partner organizations. There, they screen their subjects — who are typically 6 months to 5 years old — with the consent of the children’s parents or guardians.

Afterward, Kaf supervises her students as they write a report to parents. If hearing problems or an ear infection were detected, they recommend a rescreen, a visit to a pediatrician or a complete audiologic evaluation.

Kaf’s dedication to serving others doesn’t stop there. She often tells parents to bring their child to her lab at the Missouri State Speech, Language and Hearing Clinic. This clinic has the extensive, nonmobile equipment needed for a full evaluation. She either supervises a graduate student or does the evaluation herself.

All of this is provided at no cost to the parent. Kaf guesses this service-learning class has saved parents in the community thousands of dollars.

“It’s an intensive workload, but I feel I am their advocate. These are parents who are in the most need of that service for their children.”

Dr. Wafaa Kaf works in the audiology lab. Kaf has spent many of her 10 years at Missouri State researching ways to evaluate the hearing of challenging populations.

Advancing the audiology profession

Kaf and her students are assisting not just the community — they are helping audiology experts.

Since every child is different, audiologists need many tactics to ensure accurate screenings. Kaf and her students investigate innovative, objective ways to detect mild degrees of hearing loss and methods to weed out unreliable responses.

She and her colleagues have published their research in national and international journals for audiology professionals.

Her next study takes place in U.S., Egypt

This instrument offers an objective, painless way to measure otoacoustic emissions, echoes from within the inner ear.

Kaf is taking a sabbatical in fall 2013 for a pilot study on detecting mild hearing loss in young children. She started the study in the Ozarks and will continue it in Egypt, her home country.

“With our traditional measures, mild hearing loss is often missed. We detect it later, when the child starts to behave like he cannot hear everything or when he does not quite have age-appropriate speech and language development — but this is too late,” she said.

“I want to advance the testing protocol for newborn hearing screenings so we can detect mild hearing loss as early as possible.”

Scholar explores one of world’s oldest Buddhist Cultures

But it is. And that’s one of the things that attracted Buddhist studies scholar Dr. Stephen Berkwitz to Sri Lanka in the first place.

Although Berkwitz, professor of religious studies and current department head, originally hails from Minnesota, he has long harbored an interest in Asia.

“I became interested in studying Buddhism, particularly Buddhism in Sri Lanka, which has a very long history,” he said.

“I chose Sri Lanka as a location for my research because it continues to house a living Buddhist culture and the language that is spoken there is more closely related to the ancient Indian languages I was studying in graduate school.”

Buddhist tradition

This reclining Buddha is at a temple in Sri Lanka. It had been neglected and even damaged before steps were taken in recent years to renovate the archaeological site. Photo by Stephen Berkwitz.

Instead of focusing on the arguably more familiar Zen or Tibetan traditions, Berkwitz was drawn to Theravada Buddhism. “I was and remain interested in Theravada Buddhism, which does have a very long history and a more conservative orientation,” he said. “That combination I find intriguing – that commitment to preserving an ideal against pressures to change. Sri Lanka is particularly dedicated toward that preservation ethos. Its close connection to India also gives it a distinctive development compared to other forms of Buddhism.”

Unlike many Buddhist studies scholars, however, Berkwitz has chosen to focus on literary efforts beyond the canonical. “My research has been focused on Sri Lankan Buddhist history and literature primarily,” he said. “One thing that probably characterizes my work and interests is to go outside of a strictly monastic setting and look at how the Buddhist religion was expressed and practiced in the wider society.”

Recent research

An example is his recently published book, “Buddhist Poetry and Colonialism: Alagiyavanna and the Portuguese in Sri Lanka,” which explores the tumultuous change one poet experienced as Sri Lanka was colonized by the Portuguese. The verses of poetry translated in the book provide a window into the tremendous religious and cultural transformations of the early 17th century, when Europeans and Asian Buddhists sustained and intensified exchanges.

Berkwitz began the research for this book in 2005, attained a Fulbright scholarship to continue the research, learned to read Sinhala poetry and the Portuguese languages and spent seven months in Sri Lanka.

This is Somawathiya Chaitya, a “stupa” (domed Buddhist structure). It is located within Somawathiya National Park. Tradition holds that it was built in the second century BCE to enshrine a relic of the tooth of the Buddha. Photo by Stephen Berkwitz.

He also received a Visiting Research Fellowship to Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany in 2011-12. During that time, he made several research trips to Portugal to study the colonizer’s views of Buddhism.

During his fellowship in Germany, Berkwitz further explored the Portuguese encounter with Buddhism in Asia. “There is a large German government-funded project, ‘Dynamics on the History of Religion between Asia and Europe,’” he said. “I was among about a dozen international Fellows invited to do research, with my focus being the encounter between the Portuguese and Asian Buddhist in the 16th and 17th centuries.”

Indeed, there are only a handful of scholars in the world who focus on the areas Berkwitz studies, but that doesn’t diminish the growing importance of his work.

“It’s a small number, but it’s timely because there is a great deal of interest in the humanities in general to look at the history of cultural encounters,” Berkwitz said. “By looking at these encounters, scholars are seeing potential for understanding the role these exchanges had for shaping the development of people and places in the modern world.”

Studying civic engagement in Missouri

Using the community as a laboratory for his research, Stout, along with colleagues Drs. John Harms and Tim Knapp, conducted a series of community assessments investigating how social connectedness, membership in voluntary associations and participation in the community are related to economic opportunity.

“We want to inform policy … if we can weave together a civic infrastructure that is more inclusive, then more people will be empowered to have a voice in the future of their communities and their own lives,” Stout said.

“We want to inform policy … if we can weave together a civic infrastructure that is more inclusive, then more people will be empowered to have a voice in the future of their communities and their own lives,” Stout said.

The group also initiated a research project examining social capital and citizen participation in southwest Missouri.

They found that people in the region tend to have many interpersonal connections, high levels of participation in voluntary groups (especially faith-based organizations) and high levels of trust in others. However, their study revealed lower levels of civic engagement compared to the national average.

In 2010, Stout, Harms and Knapp completed the first-ever State Civic Health Assessment and they are now working on the second.

More recently, the team collaborated in the Neighbor for Neighbor initiative to bridge gaps between diverse populations within neighborhoods affected by economic hardships.

“The idea is to use small incremental changes to build trust, to increase social connectedness, and to empower people to work together to solve problems,” said Stout.

Working with endangered Asian elephants

Schmitt has worked with elephants for more than 30 years. In addition to his role at Missouri State, he serves as the chair of veterinary services and director of research and conservation at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Center for Elephant Conservation. In this capacity, he oversees the care of about 50 elephants for Ringling Bros.

Although elephants are smart, charismatic animals, they can come into conflict with humans.

“In attempts to keep elephants from damaging their crops and property, people come into direct conflict with elephants,” Schmitt said. “Sometimes the elephants win; sometimes people win.”

Due to this conflict and an aging elephant population, Schmitt’s work with breeding has become even more important. In 1999, Schmitt became the first researcher to produce an elephant from artificial insemination.

Since then, he has been at the births of about 20 elephants that were the result of artificial insemination.

“Artificial insemination allows us to provide genetic diversity by breeding (females) with unrelated males,” Schmitt said. “It gives facilities the opportunity to repopulate endangered species without having the housing for the males at the time.”

Schmitt added that if facilities are going to participate in breeding programs, they are required to have the space to house the males as they grow up. According to Schmitt, space won’t be a problem in several years as the aging elephant population is nonreproductive with the average lifespan in the upper 40s.

According to Schmitt, one way people can help these animals is to simply learn more about elephants.

Exploring how humans interact with computers

Working with an international group of human/computer interaction researchers, Brahnam has published widely and performed several studies that investigate the extent of agent abuse. In addition, she has examined agent abuse as an ethical issue and has proposed methods for designing agents so they are less likely to elicit these negative responses from users.

Brahnam uses her technology expertise in multiple other research projects — one of the primary areas being medical decision support systems.

An example of her contribution in this field is the development of the pilot Infant COPE (Classification of Pain Expressions) database and evaluation protocols, which includes 204 photographs collected of 26 healthy term infants.

The infants were photographed at Mercy Hospital in the neonatal unit while they were experiencing a number of benign nonpain stressors and an acute pain stimulus (the heel lance needed for the state-mandated blood exam).

This study was the first to investigate automatic neonatal pain detection using facial expressions.

Writing about British culture in the Nuclear age

Dr. Catherine Jolivette, associate professor of art and design at Missouri State University, will soon release a new book, “British Art in the Nuclear Age” (Ashgate, 2014), which addresses the role of art and culture in the realm of nuclear science and technology, atomic power and nuclear warfare in Cold War Britain.

“Researching for this book really brought to light that there was no one homogenized response to living in the atomic age. Past historians have had a tendency to generalize about everybody living under a cloud of anxiety and fear,” Jolivette said.

The book, which is a collection of nine original essays by international colleagues in a number of disciplines, builds upon her previous book on landscape and art in Britain in the 1950s that only touched briefly on how changes in science and technology were perceived by British artists during the mid-20th century.

“It’s not just about militarism or nuclear weapons. It was also about the hopes and potential of science for good, and holding those two things in balance,” Jolivette said.

Being British herself, she is excited to be part of the landscape of this part of art history.

She finds inspiration in engaging in dialogues with colleagues outside of her discipline at conferences, and is currently collaborating with a group of other scholars on finding funding for a mobile application related to their collective research.

Improving literacy in children

It is taught early and tested often, and it is a lifetime skill that should be expanded to improve comprehension in daily life.

Although children often enter school with a basic grasp of reading and language, educators must be prepared to engage students to improve these skills.

Dr. Deanne Camp, professor of reading, foundations and technology and the graduate literacy program coordinator at Missouri State, understands the challenges of reading instruction and prepares educators for overcoming them.

Her primary research areas include literacy development, comprehension and struggling readers.

She has authored and co-authored approximately 10 journal articles or book chapters in the last three years, tackling topics like the importance of reading aloud, teaching study skills and developing writing lessons for early elementary school.

Keeping grape populations healthy

Here, researchers like Dr. Wenping Qiu, director, and Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang, associate professor at the William H. Darr School of Agriculture, explore grape genetics. They want to increase the profitability of the grape and wine industry, ensure its stability and improve human health with their genetic findings.

One of the primary grapes studied at the center is Missouri’s official state grape, the Norton — which is grown at the State Fruit Experiment Station on the Mountain Grove campus. The researchers study disease resistance in order to keep the plants healthy.

“Norton, (scientific name Vitis aestivalis), the official grape of the state of Missouri, is grown in many U.S. regions where production of V. vinifera (the European grape used for most wine-making worldwide, e.g., pinot noir) requires extensive pesticide use for fungal diseases,” Hwang said. “It has been reported that Norton is hardy and resistant to several fungal pathogens including powdery mildew, downy mildew, Botrytis bunch rot and black rot.”

With some of the most recent findings, the research team hopes to expedite efforts to breed the Norton grape with the ultimate goal of improving viticultural performance and enological quality of new grape varieties well-adapted to Missouri conditions.

Sharing the healing power of art

Since becoming a registered art therapist in 1987, she has hosted a variety of workshops and researched art therapy for children in pediatric oncology units and patients who are terminally ill.

Knowing the importance of art in life, especially in the lives of children, she organized efforts to donate more than 150 boxes of art supplies and 75 boxes of craft supplies to communities affected by hurricanes Katrina and Rita. That’s when she founded Art on Wheels-Missouri, which later came to the aid of the community of Joplin — where Fowler raised her family — after the town was ravaged by a tornado in May 2011.

“When we worked with the kids after the Joplin tornado, we’d often have a group process where we’d all draw people…and we did look at how they responded,” she said. “When I saw the children’s work, I could tell by the colors they use, by the way they worked … and what they omit, what they were experiencing.”

When they see work with hard scribbling, torn-apart imagery and/or the use of dark colors, a therapist might deduce that a child was experiencing anxiety, Fowler said. One common theme children drew after the tornado was butterflies. Although no one can be sure why these showed up in so many drawings in the aftermath, it is an area that has intrigued Fowler and she plans to do further research.