Archive for 2016

Answering big questions through statistics

Resiliency testing is just one example of many research projects Dr. Erin Buchanan, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State University, has published in recent years. She collaborates with undergraduate and graduate students in her statistics lab as well as with a clinical psychologist at University of Mississippi, Dr. Stefan Schulenberg, on many projects regarding the meaning in life.

“How does meaning in life affect negative life outcomes? That’s the big, broad question. Then we narrow it down to, how does a scale work in predicting negative life outcomes? Does it work the same way for everyone?” said Buchanan. “By negative life outcomes, we mean depression, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, drinking – those sorts of things.”

Clinical people say this a lot, “The right therapy for the right patient at the right time,” or something to that effect. Computer-adaptive testing is built on that. “The right question for the right person at the right time.”

Adding technology to the equation

Buchanan’s role in research projects is to develop scales, test the scales to see if they measure what was intended, and to analyze the variance across demographics. Currently, she and her students are in the midst of testing 47 unique scales with students in introduction to psychology classes. She also collects results through MTURK, Amazon’s answer to incentivized testing.

As a daughter of two computer programmers, she said she felt like the black sheep entering the field of psychology, until she realized that as an experimental psychologist focusing on quantitative analysis, she spent much of her time programming, too – in approximately 12 different languages.

“I’ve always been good at math. I knew I never wanted to work directly in a helping profession. That was never my goal,” she said with a laugh.

Just the way you phrase things can change whether a respondent will say yes or no. Just because it’s culturally relevant.

One of the most prominent projects for Buchanan is to develop a computer-adaptive test. This test starts with an average score, but depending on how a respondent answers, the following questions may be more positive or negative, or might increase or decrease in difficulty.

“Social desirability can come into play, where people will go, ‘Oh, you want me to say positive things,’ or you end up with all happy or all negative answers, and you don’t get anything in the middle,” she explained. “We’re trying to statistically stretch the scale out so we might be able to better predict the negative-life outcomes that come with that.”

Answers divided by race

In the early 2000s, the south suffered two major disasters. After Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill, Schulenberg, director of the Clinical-Disaster Research Center at Ole Miss, contracted with Buchanan to test the resiliency of the people of the area.

“I hear this a lot from clinical students, ‘Why do I need statistics? I just want to help people.’ My answer is, ‘Because you have to be able to read these articles and understand the implications the variations in responses people make.'”

“We have a primary focus in disaster mental health and a secondary focus in positive psychology,” said Schulenberg. “Dr. Buchanan has been a tremendous asset to our team for a number of years incorporating sophisticated statistical analyses.”

The resiliency scales were found to be valid and effective, but analysis showed differences between white and black respondents.

“While we end up with the same overall score, white participants were much more likely to have a real short spread of scores. They would only pick the middle, while the black participants would pick the entire range,” she said. “If you’re black in Mississippi you’re much more likely to be one or two steps below socioeconomically. Obviously that’s going to matter for resiliency, right? We were trying to argue that the effects weren’t due to innate resiliency of people, but more due to circumstance.”

Previous research had shown that culture-fairness plays a part in standard and computer-adaptive testing, sometimes resulting in artificial differences because respondents inferred something into the question that might not have been intended. Similarly, Buchanan noted that black people from an early age learn a different dynamic of power and authority, causing differences in way they may perform on tests. So, word selection is key – whether it’s a test about your resiliency or a statewide mandated comprehension test, the testing agent desires representative results.

An everyday life of Biblical proportions

“The house I grew up in and every school I went to was destroyed,” said Matthews. “Much of me went away in the sky, and yet I was able to go back down there and identify what was remaining of the structure that was my childhood home.”

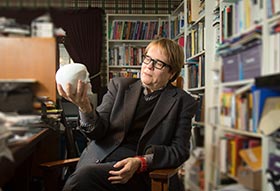

Matthews took a picture of the ruins and uses it in class as a way of talking about how space is still present in our memories. This speaks to his area of expertise: the history and culture of the Biblical era. Though physical remains may be few, the everyday lives of the people from this time can be better understood by studying the stories and artifacts that they left behind.

‘What the devil are they doing?’

How do we learn more about the ancient world? This is one of Matthews’ research questions. He says it’s important to understand that we tend to filter everything through our modern scope.

“We are trying to find out what the devil they were doing. Unfortunately, this often means applying our modern viewpoint and totally skewing the whole thing.”

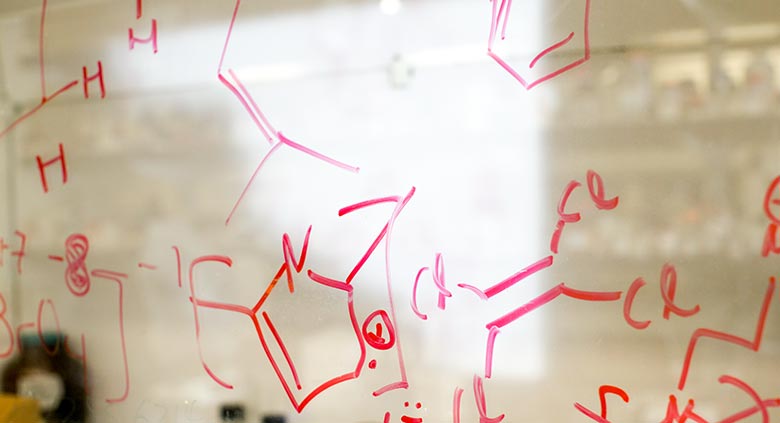

Biblical narratives, like most stories, assume that the audience shares a defined set of social understandings or customs. When we don’t know what these customs are, we must use several different methods to try to discover them.

“I have made good use of modern research and analytical methods in the social sciences —sociology, anthropology, psychology, communications — to evaluate the ‘human moments’ in the narratives,” said Matthews. “For example, when I examined the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38, I looked for the social cues in the story: clothing, marriage status, power relationships, gender, speech patterns and the physical placement of the characters.”

Matthews applied these methods when writing and researching his most recent publication, the fourth edition of “The Cultural World of the Bible: An Illustrated Guide to Manners and Customs.” It is one of 17 books he has authored, and he has published numerous articles on the subject as well.

Putting together a large puzzle

“When we say cultural world, what it basically says to people is that we’re going to talk about everyday life. What did they eat? What did they wear? How did they celebrate? What were their burial practices? What kind of weapons did they use?” he said. “All kinds of topics like that.”

There are several ways we can learn the answers to questions like these: written records, including the Biblical text and extrabiblical documents; physical remains such as tomb paintings and grave goods, garbage heaps, and the ruins of buildings, which are studied by archaeologists; and the study of both modern and ancient cultures via analogy.

“Reconstruction of the world of ancient Israel is like putting together a large puzzle,” said Matthews. “Some of what I included in the book came from my own travels in the Middle East, some from basic research and discussion with colleagues, and some from studying how other authors shaped their treatment of the subject.”

Talking about talking: analyzing conversations

Matthews, who has been a Biblical scholar for more than 30 years, has also recently focused on the conversations that occur in these Biblical narratives and what they can tell us about the characters and their daily lives.

“There is a lot of conversational analysis in communications, sociology, anthropology and psychology,” said Matthews. “I got interested in seeing how the different disciplines analyzed conversation, but, of course, what I’m working with is text. I have narratives with embedded dialogue.”

“It allowed me to develop a richer understanding about the setting of the story, the human drama associated with a childless widow, the importance of clothing as a social marker and the role that place—physical location—holds in determining how humans interact.” (Matthews on studying the human moments in narratives.)

Matthews studied the way these disciplines researched conversations, which mostly consisted of analyzing live conversations. He applied many of the techniques and concepts they used to the narratives he was studying and was able to discover previously unknown contexts. His book, “More Than Meets the Ear: Discovering the Hidden Contexts of Old Testament Conversations,” was published in 2008 and led to a journal article in 2014, “Choreographing Embedded Dialogue in Biblical Narratives.”

Matthews graduated from Missouri State in 1972 with a bachelor of arts degree in history, and received his masters and doctorate in Near Eastern and Judaic studies from Brandeis University in 1973 and 1977 respectively. He has spent most of his career focused on the historical aspects of religious studies, and looks forward to continuing his studies on ancient Biblical culture and writing about what daily life was like thousands of years ago.

Further reading

Small particles, big impact? Exploring how nanomaterials decompose

Silver, known for antibacterial and anti-odor properties, may be in everything from athletic wear to cutting boards. Zinc oxide, which prevents sun damage, has been used in sunscreen and woven into fabric for clothing. Carpet may be treated with nanoscale materials that prevents it from absorbing spills. Carbon-based nanomaterials are found in cell phones and televisions.

One thing is sure: The trend of nanotechnology means we are all more likely to buy goods with these tiny particles, and, later, dispose of these products.

What’s less certain is the affect of these nanomaterials on the environment as these goods decompose in landfills.

“I wanted to do research with undergraduate students, not just students studying for a PhD. Here are Missouri State, some of my best research has been done by undergraduates.” — Dr. Adam Wanekaya

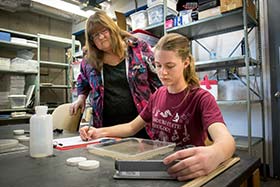

Dr. Adam Wanekaya, associate professor of chemistry, has researched nanomaterials since his days as a doctoral student in the early 2000s.

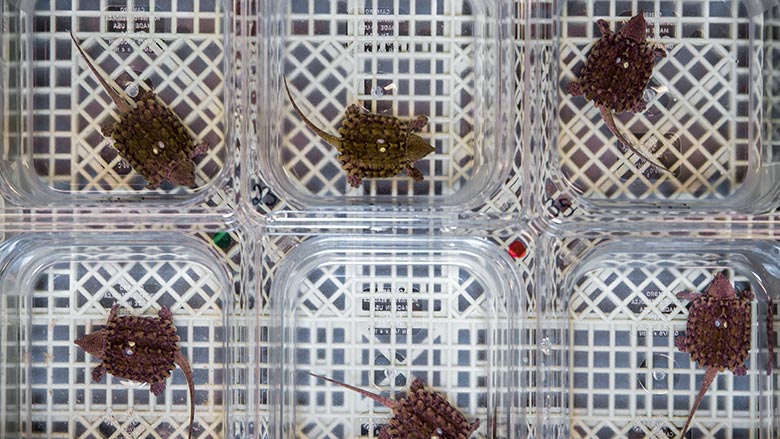

For the last three years, he has been leading a project with undergraduate and graduate students at Missouri State who are studying how nanomaterials age in an accelerated weathering chamber. The research shows how these particles will react in conditions similar to those they would experience outdoors.

“What is the fate of those particles after three, 10, 20 years? We want to make sure they don’t contribute to diseases such as leukemia, or cause harm to plants, animals or the environment,” Wanekaya said. “Some of us recall how asbestos was previously thought to be a wonder material, only to later realize it was the cause of many deadly diseases.”

African collaborations

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is originally from Kenya, and came to the U.S. for doctoral studies. He started working at Missouri State in 2006. He is currently part of the Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program, which encourages collaboration between scholars from Africa who now live in Canada or the U.S. and scholars who currently live in Africa.

Wanekaya traveled to a university in Nigeria for six weeks in 2015. One scientist he met there, who works with solar cells, came to Missouri State in January 2016 and planned to stay for six months to engage in research on campus.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Creating conditions that mimic the outdoors

At least once a week, senior Molly Duszynski heads into a chemistry lab at Temple Hall.

First, she attaches carbon nanotubes to glass slides.

Next, she takes the slides to an accelerated weathering tester, where they fit into holders designed for them.

“It has been really awesome to learn about carbon nanotubes and the overall process of real research.” — Molly Duszynski, biochemistry/microbiology double major

Now, the chamber is closed. It’s time for Duszynski to make decisions about what kind of conditions the slides will face. The chamber has UVA-340 bulbs, which provide the best possible simulation of sunlight. It is also attached to a tank that holds water free of minerals or impurities. She, Wanekaya or others on the project may adjust lighting, humidity, temperature and more to simulate sunlight, rain and dew. The chamber can create conditions for night, evening, afternoon or morning, or cycle through those.

In a few days or weeks, the machine can reproduce the decomposition that would occur in months or years outdoors.

Wanekaya’s team has chosen to mostly focus on conditions that are slightly hotter than normal, in order to see what the carbon nanotubes would do if they were in a landfill in a part of the country with high-intensity sunlight.

They chose carbon to study first.

“This is a good basic material because we can predict a bit about carbon’s behavior,” Wanekaya said. “We are starting with something more simple before we move on to something a bit more complex.”

Approximate conversion chart

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula for how many hours in a weathering chamber equals a time period in the outdoors, according to Q-Lab (the company that makes the QUV Weathering Tester used in MSU’s chemistry lab). That’s because the relationship between tester exposure and outdoor exposure has so many variables, such as geographic latitude of the exposure site, altitude, random variations in weather from year to year, etc. One recent graduate student in Wanekaya’s project, however, was using this approximate ratio: 2,100 hours of weathering tester exposure = About one year in the Florida sun

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Preliminary results, collaborative papers

Wanekaya says the research is yielding some preliminary results.

The team can see that the shapes of the carbon nanotubes change after treatment in the chamber. Before treatment, the nanotubes are more or less linear. After, they are coiled. Using various technologies, the team has shown there are other substantial differences between groups of control nanotubes, which are not subjected to tests, and nanotubes that have been aged.

“Now, we need to find out whether those changes are good, bad or neutral. That’s our next step,” Wanekaya said.

The team shared a tested group and a control group with colleagues in the Missouri State biology department. Those researchers exposed yeast, bacteria and other cells to both the control group and the aged group of nanotubes. They wanted to see if either group of nanotubes was potentially toxic to those materials.

One team found that treating yeast with either aged or control carbon nanotubes was significantly toxic to the yeast cells. Results of that study have been submitted for publication to the Journal of Nanoscience and Technology.

No significant differences were observed in bacteria and plants exposed to both the aged and control carbon nanotubes.

Wanekaya plans to keep working with these tiny particles.

“Nanomaterials are very exciting. They have novel properties that can be used for so many things.”

How small is nano?

In the International System of Units, the prefix “nano” means one-billionth. Therefore, one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. It’s difficult to imagine just how small that is, so here are some examples:

- A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick

- There are 25,400,000 nanometers in one inch

- A human hair is approximately 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide

- One nanometer is about as long as your fingernail grows in one second

Source: United States National Nanotechnology Initiative

Wanekaya’s other research interests

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is seeking many ways to use nanotechnology to benefit humans and the environment. He is involved in research regarding:

- Cancer treatment (part of a team that received a grant from the National Institutes of Health)

- Cancer detection

- Detecting and removing toxins from the environment

For more about his work regarding cancer, see a past Mind’s Eye story about one of Wanekaya’s collaborators.

Further reading

A working writer

The pitch was going well; the executive was laughing and taking notes. But then she asked an unexpected question. Could he change the gender of one of the lead characters? A female lead would be more inclusive of the network’s demographics and provide a vehicle for one of its rising stars.

Amberg remembers that it wasn’t as simple as saying ‘yes.’ He had to quickly run through the plot, scanning for the “ripples that come from tossing that rock in that pond. I knew the story so well that I was able to do that in the moment. The fact that I was able to answer authoritatively about the specifics of how I’d adjust the story gave her the confidence to buy the project in the room.”

With that sale, Amberg earned membership in the Writers Guild of America, a life-changing milestone that resulted in larger contracts and meaningful benefits. The experience also affirmed an essential principle: that flexibility is the foundation of life as a working screenwriter.

Now, as the coordinator of Missouri State’s screenwriting programs in the department of media, journalism and film, Amberg helps emerging writers develop their skills and learn to navigate the industry.

Amberg’s creative activities keep his knowledge sharp. Since joining Missouri State in 2013, he has completed contracts with Disney Channel and Cartoon Network. He makes regular trips to Los Angeles, where he meets with contacts at film, TV and Web entertainment companies, including Nickelodeon, Amazon and Awesomeness TV. His work has been recognized with a number of awards, including Best of Competition in Faculty Scriptwriting at the Broadcast Education Association Festival of Media Arts.

Lessons from the industry

Amberg is straightforward with students about the industry’s unpredictability. Companies’ mandates shift; executives get reshuffled; different personalities respond to different types of material. And these all affect whether a writer’s work gets produced.

But Amberg also focuses on the constants, like the importance of developing a strong work ethic, mastering the fundamentals of story and – most importantly – understanding the writing process.

“I don’t want anyone to be in a situation where they find themselves staring at a blank screen,” he says. “I want them to know how to tell a character-based story that is held together by the tools of writing, not dependent on one idea. And if they get some great, awesome idea, they will be able to execute it. And if they get hired onto a project, they’ll know how to deliver the best version of someone else’s idea.”

Amberg also encourages humility and perspective. “Everyone in this business is working hard, and no one came to Los Angeles with the goal of making someone else’s dream come true. It’s important to be kind to other people and assume that everyone’s doing their best. And when the planets align and a project works, it’s great.”

Amberg often shares with students that when he first started out, he believed compliments indicated a meeting was going well. As he gained experience, he learned that questions, not compliments, are the true sign of a project that’s resonating. “When people are really interested in something, they want you to make changes,” he says.

This dynamic can feel bruising to creatives, who are sometimes considered overly protective of their work, and Amberg empathizes. “Screenwriting is unlike many other kinds of writing, where the writer is king,” he says. “But it’s important to remember that the executives you work with are smart, creative people, too. They’re tasked with thinking strategically about multi-million dollar projects. And their changes aren’t arbitrary; they just have more information about what they need.”

According to Amberg, the ability to collaborate and create a production-ready script is essential, not only for career success but for the strength of the story.

“You love your script,” he explains. “So you change it and adapt it to survive in the market – the same way you’d raise a child to survive in the world.”

Fighting the past for a more active future

To Perkins, this wasn’t a surprise. She has spent much of her career analyzing underrepresented populations, such as African Americans and the elderly, in the areas of exercise and sports psychology.

“African American women are one of the least active segments of the population,” Perkins said. “In Springfield and on campus, we have a small African American population, so I want to know if they exercise, if they use the recreational facilities on campus and their perceptions about exercise and campus climate.”

Her experience at the Rec Center inspired her to begin researching exercise trends among female African American students at Missouri State with the ultimate goal of developing a new physical activity program designed to revolutionize exercise trends at Missouri State.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Researching the underrepresented

Perkins’ research into minority groups indicates that a population’s overall trend of activity exists due to a complex variety of external factors – such as community, education and environment – as well as internal factors. Her research into these factors helps her to understand the best methods for improving exercise trends for different groups of people.

“In kinesiology, we prescribe exercise just like a doctor proscribes medicine.”

“In kinesiology, we prescribe exercise just like a doctor proscribes medicine. Not everyone should be doing the exact same workout. The same strategies don’t work for everyone,” she said.

In the past, Perkins has investigated several possibilities that may explain why African American women are less active.

For instance, her research has shown that African Americans in general may have less opportunity for participating in sports and other physical activities that are primarily offered in white communities. This lack of opportunity for activity early on in life can lead to lifelong habits that require extra help and effort to change.

“Everyone deserves help,” Perkins said. “Groups of people that are not represented in research are unlikely to be getting that help.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Encouraging exercise to prevent disease

As a researcher, Perkins’ goal is to understand these psychological and social factors about physical activity, but she doesn’t stop there – her goal is also to change the statistics by breaking through the barriers with targeted interventions to help these women get out and get active.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2011, African American women were 80% more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic white women.

According to Perkins, the importance of exercise can’t be overstated. She said a lack of physical activity can negatively affect a person’s health and lifespan in many ways, and it is troubling that an entire demographic group is at risk for insufficient physical activity.

“Exercise can prevent chronic disease, which is a fact a lot of people just aren’t aware of,” Perkins said. “I want to figure out what psychological factors influence sedentary behavior and what social or cultural factors lead to African Americans being less physically active and having a higher incidence of obesity and chronic diseases.”

Empowering a diverse campus to meet the needs of every individual

After collecting preliminary data about physical activities among female African American students, Perkins received a small cultural diversity grant from the Association of Applied Sport Psychology to further develop the study. She conducted focus groups to learn more about the perceived barriers to a workout regime, and most prominently she heard “lack of time” and “lack of motivation.” In her initial analysis of the responses, though, she also uncovered some findings more unique to the demographic, like difficulties with dealing with hair post workout and feeling socially isolated.

She hopes that by providing opportunities for some of the students most likely to have experienced obstacles to physical activity, she can contribute to a campus environment that is not just healthier, but also more inclusive of its diverse population so every individual can be empowered to meet his or her needs.

“I ask them: In a perfect world, what would an exercise program look like for you? Ultimately my goal is to help get students moving. I want to get them now in college so they’ll continue to be active as adults after they graduate,” she said. “If I can figure out what barriers prevent them from exercise, I can help them find a program they can stick with so that they can live healthier lives. It’s about finding what best fits the needs of the people you work with.”

Rethinking education: How to engage students who have special needs

“Research shows that 20 percent of students have these disorders throughout their childhood. A lot of those things that go untreated and unhelped get worse as students get older,” said Adamson, an assistant professor of counseling, leadership and special education at Missouri State University. “It tends to be a high need.”

So she wondered about the possibilities. What if teachers knew how to better identify and help such students? What if those students knew how to seek help for themselves? And how might that bring about a better future for tomorrow’s leaders?

Identifying the problem

Adamson is working with local public schools to help a small section of students who struggle with following through on classroom engagement and aren’t learning at the same rate as their peers. Specifically, she wants to know what systems, supports, and interventions can be placed in schools to support teacher training and student outcomes.

Such students may have educational behavioral disorders, which differs from medical behavioral disorders. The question is whether the disorder affects performance in the classroom.

“It isn’t because they aren’t capable,” Adamson said. “It’s because they aren’t able to sit in class and sustain until the class ends.”

What happens then, Adamson explained, is a cyclical issue in which entire classes fall behind as teachers reteach the same content to try to catch those students up.

Using a single case design, her research focuses on like groups of students to find direct relationships between interventions and how teachers’ and students’ behaviors change on days when data are collected.

Getting teachers to think like movie stars

However, the answer doesn’t lie in addressing behavioral concerns with the students alone, Adamson noted. Focus on adjusting the behavior of the teachers from an entertainment angle, and better engagement will follow.

“We know the key to students being successful is having dynamic teachers,” she said. “The biggest impact on students staying in school and having good outcomes is school engagement, which comes from making a connection with the school.

“As teachers, we’d better be the best actors there are. Every day that we’re teaching a class, we’re putting on a performance. We’re trying to draw students in as the crowd so they walk away, remember the lesson, and want to tell everybody about it.”

Behavior management is also the top reason teachers leave the profession, Adamson said, noting that training the teachers and getting students to become engaged could change a child’s trajectory.

“Kids who have emotional and behavioral disorders have worse post-secondary outcomes such as not going to college, not getting jobs and going to prison,” she said. “They’re starting out on this horrible track. It’s our job to find out what we can do to help improve this process for them.”

“I think as a nation, we need to support students who have mental illnesses and people who have mental health issues in general. Those kids who have behavioral disorders really struggle understanding the context of school because it’s so different from their lives and environments they’ve been in.” — Reesha Adamson

The long-term benefits

Starting students on a better track also includes helping them manage their mental health care as adults. This is key as children reach 16 years of age and may think they don’t need help anymore.

“People stop receiving services because they look around the waiting room and say, ‘I don’t look like that person over there. I don’t need this help,’” she said. “So we have this falling out when they stop losing this care. Our goal is to get them to continue that care to give them strategies for success after high school.”

Further reading

Transforming student writing in the Ozarks

Those are the research questions Dr. Keri Franklin hopes to answer.

Those are the research questions Dr. Keri Franklin hopes to answer.

Franklin’s work has led to the establishment of the Center for Writing in College, Career and Community, an endeavor that seeks to support improving student writing for all students, and especially those teachers and students working in rural schools. This new center is the home to the Ozarks Writing Project.

OWP is supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Education, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the Missouri Department of Higher Education.

Franklin, Missouri State University’s director of assessment and associate professor of English, is the founding director of OWP, which provides professional development to thousands of area teachers across disciplines —such as science, math, social studies, and career technical educators.

“Teachers have expertise to share and few opportunities to share it outside of the classroom,” she said. “The OWP model focuses on bringing teachers together to teach each other and research their own work.”

Over the last decade, Franklin has secured $1.3 million in grants to carry out the organization’s mission: to impact student writing outcomes as well as teachers’ beliefs and practices.

“I love getting community partners together and seeing people achieve and grow. To create a network that could go on without me — that’s bigger than me — I’m really proud of that.”

Measuring student improvement

Franklin’s most recent research study was in partnership with National Writing Project and funded by the Investing in Innovation (i3) grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

Franklin’s most recent research study was in partnership with National Writing Project and funded by the Investing in Innovation (i3) grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

She was one of 12 site directors chosen for the grant, which resulted in more than $600,000 in funding for OWP’s College-Ready Writers Program, a partnership between Missouri State and the Monett, Laquey, Branson and Richland school districts.

The study focused on improving academic writing in grades 7 through 10, supporting rural educators in teaching academic writing, specifically argument writing, and working with school districts to sustain the work beyond the grant period.

The results are promising.

Ultimately, CRWP had a positive, statistically significant effect on the four attributes of student argument writing—content, structure, stance, and conventions—measured by the National Writing Project’s Analytic Writing Continuum for Source-Based Argument. In particular, CRWP students demonstrated greater proficiency in the quality of reasoning and use of evidence in their writing.

Students of a Laquey, Missouri, teacher who participated in that program saw a 17 percent jump in scores on the state test in one year.

“These kinds of gains and partnerships are years in the making, and they are the result of a cadre of teacher-consultants in school districts around southern Missouri who are committed to the teaching of writing,” Franklin said.

Leading the way

OWP began as a satellite site in 2005 with 10 teachers from elementary, middle, high school and community colleges, including Franklin who was pursuing a PhD in English education. In 2008, with multiple support letters from teachers and school districts, OWP became a full National Writing Project site — one of nearly 200 located at universities across the United States.

Since starting at Missouri State, Franklin’s research areas have grown to include the impact of professional development on writing outcomes, digital writing and writing assessment.

While she continues that research, she faces her next challenge head-on: to bring the transformational experience of professional development to teachers in rural and high-needs schools for free.

It is a feat that looks likely for OWP, an organization on the forefront of shaping what the future of writing education will look like in the U.S.

Further reading

Eye to eye or eye for an eye

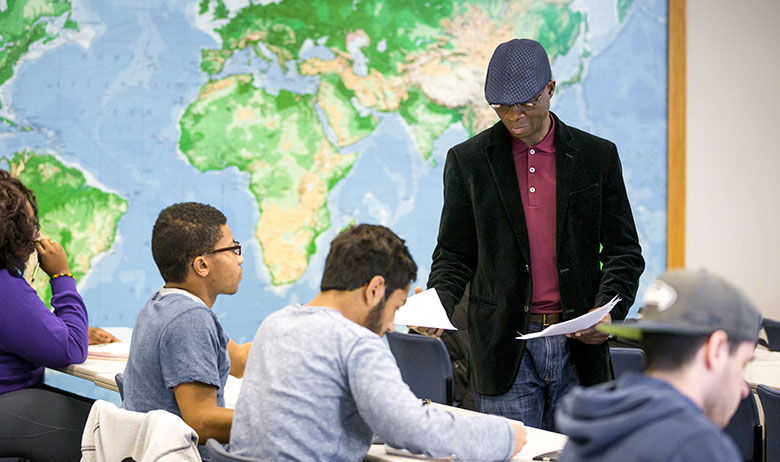

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

“The definition is always what others do to us. It’s always going to be a guy or group on the other side of the street,” he said.

Although approximately 50 such agitators or groups exist in West Africa, Oyeniyi has written and presented extensively on Boko Haram, which has garnered much attention from the media since it was assembled in the early 2000s. According to Oyeniyi, this group is easier to study than most since the founder Muhammed Yusuf recorded sermons and distributed them widely in the form of CDs, DVDs and leaflets in the early 2000s.

“There are people who will come out boldly to address the public in the form of open air preaching. What are they agitating for? Their belief system,” Oyeniyi stated.

The initial sermons are contraband now, but founding members of Boko Haram can serve as a lead for Oyeniyi. These ex-members offer insights into what drives the agitators to don the suicide vest. Moreover, these former members also could bridge the gap to begin peaceful negotiations.

As a social historian, Oyeniyi looks for patterns within the movements of specific groups and traces the roots of the conflict. Tracing the trends, he is able to build a profile of what an agitator group looks like and what the likely outcomes could be. He begins to postulate: What are they really fighting for? How are they getting their training? Who are their allies? Who funds them? Then, he and his collaborators create suggestions and form conclusions that the government can work with to address the root of the issue.

As much as possible, I want to see a world where we are all free. Free to express our anger against established institutions and individuals and also free to be corrected. So I long to see a Nigeria that is peaceful. I consider this my own way of contributing to it by exposing what is going on.

Greed versus grievance

Greed versus grievance

What he has to say might shock you. He understands Boko Haram’s complaints.

“They are requesting something, part of which includes the fact that the nation-state is, as it is, not properly governed,” said Oyeniyi. “So they have social grievances, and they have also what I call greed.”

Their grievances are at least, in part, related to a religious struggle as old as time. Two categories of Muslims abound in Nigeria: those who believe the Quran is not open to interpretation and want to see Sharia law enforced as the indisputable law of Nigeria; and those who see the Quran as open for interpretation and therefore welcome innovations, like Western education. In Nigeria, the second category is the majority.

If you eliminate Boko Haram today, you still have 49 other groups to deal with. It should not be about eliminating a group or set of groups, but looking at the causes.

One of the primary reasons behind the formation of the Boko Haram – which means Western education is a taboo – was the removal of innovations from Islam. Since the colonial period, there is no dearth of groups crusading against this, and these groups unite in their belief that other Muslims, especially those in power, are corrupt. Since 2000, Boko Haram has engaged in heated ideological and doctrinal debates with other Muslims, who found the group’s teachings unwelcoming to progress and sought state intervention to rein the group in.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

“The state itself needs to understand at what point human rights kick in. Boko Haram may be a terrorist group, but they also have fundamental rights that must be respected. We must recognize this if we’re going to fight and win against Boko Haram,” said Oyeniyi. “As things are, the government has failed to realize that dissatisfaction in the eyes of man will almost always force him to take radical actions.”

In summer 2015, Oyeniyi traveled to his homeland of Nigeria to collect documents Boko Haram released before they decided to go underground. Now, he will translate and make them available in the form of a book. By doing so, he hopes to gain further insight into what genuine concerns stand behind the rhetoric.

Taiwan: Where politics, history and geography collide

According to Dr. Dennis Hickey, distinguished professor of political science and director of the graduate program in global studies at Missouri State University, that’s essentially what happened between China and Taiwan in 1949. For decades, Taiwan was recognized as the sole government for all of China, wherein they even held the UN seat for China, until 1971.

The People’s Republic of China (mainland China) and the Republic of China (Taiwan) don’t agree on how this all transpired, and Hickey said this remains the biggest hurdle in Sino-American relations to this day. It’s fascinating and frustrating, and it’s what has driven his research for the past 30 years.

“Taiwan is no longer a dictatorship; it’s a multi-party democracy, which is great for American interests because we support democracy,” said Hickey. “It’s also a potential problem because not everyone agrees that Taiwan should remain as the Republic of China. There are some people who never want to unify with the mainland, which could reignite the Chinese civil war and involve the United States.”

If he could devise a perfect solution for the situation, he’d have them “agree to disagree” and postpone any decision for 50 years.

As an adolescent, Hickey became interested in East Asia: His father, as well as many of his friends’ fathers, had fought the Japanese in World War II, and he watched the Vietnam War unfold on the nightly news.

Policy relevance

Because China is so important– home to more than 1.3 billion people and the world’s second largest economy – Hickey strives for policy relevance in his research to give U.S. officials options to prevent a conflict with China.

He has advised heads of state in Taiwan and in the United States, even testifying before a U.S. Congressional Commission created to monitor America’s relationship with China. His credibility with other academics, the media and government officials rests on the fact that he looks at each issue objectively.

For example, recently he was asked to conduct research on a dispute over several small, uninhabited islands in the East China Sea. He searched documents, interviewed officials, presented his findings and published an article in a top tier journal.

“In the East China Sea, these islands have three different names depending on where you are. They’re really little specks, but there’s oil and gas underneath them. They’re claimed by China, Taiwan and Japan. China and Taiwan both believe that Japan stole these islands during the first Sino-Japanese war in 1895, and they want them back,” said Hickey. The Japanese government formally nationalized the islands in 2012, “sparking the largest anti-Japanese riots in that realm of the world since WWII,” he added.

“Now when I visit Taiwan, I can change planes in Beijing. Why is that a big deal? Well, until recently, you couldn’t get from one side to the other directly because of the political problems. Now, there are millions of tourists from the mainland. They go and take pictures at the presidential palace and the flag. They can’t fly that flag in the mainland.”

Recent improvements

Within Taiwan, there are disagreements about whether Taiwan should be an independent country or remain as the Republic of China. Chen Shui-bian, who served as president from 2000-08, tried to promote independence, and Hickey noted that this movement eventually served to improve relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China.

“I think Chen scared the mainland. That’s when they got a little bit more reasonable instead of just bullying Taiwan,” he said. “They’re talking now, they’ve got direct trade and travel, and they’ve signed 21 major agreements in the last seven years.”

Many times, he collaborates on publications with current and former students who continually offer fresh perspective. In fact, it’s the thought-provoking questions from his graduate students that occasionally inspire his research in the first place.

Agree to disagree

Traveling to and from Asia to be part of this policy discussion for more than three decades, Hickey has established trusting relationships with people on both sides, though he jokes that a little suspicion arises from some mainland Chinese contacts. But are they against his work?

“Not at all. They know I do not support Taiwan independence. There is a Chinese government in Taipei and a Chinese government in Beijing. They are okay with that,” he said.

When he began this research in graduate school, the economic and political systems in both China and Taiwan were quite different.

“The two sides have moved closer economically, but not politically,” he observed. This is the primary reason he thinks the dispute should be shelved for 50 years.

“They should sign a peace agreement and agree to disagree what it means to be China and ratchet down any potential problems,” he said. “It’s their own internal affair. We shouldn’t be pushing them to unify or separate – just don’t let them start World War III.”

Further reading

Broaden your horizons: Consider a master’s in global studies

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.