Archive for 2017

Can you change your personality?

Does she feel empathy for those she squashed to get to the top?

The studies of Dr. Amber Abernathy say no.

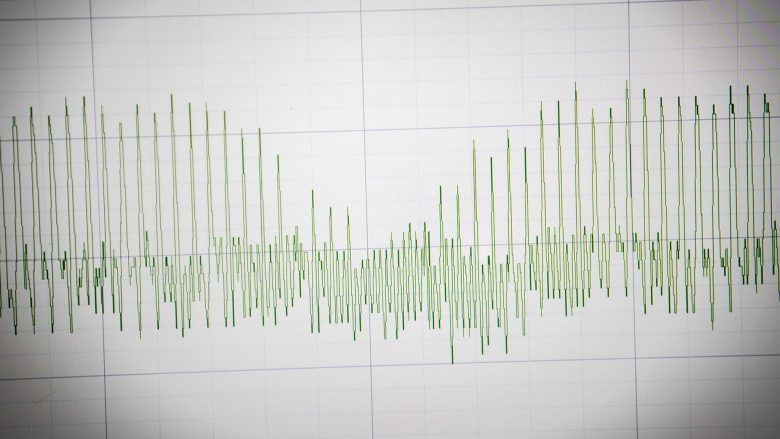

“Every human should have a physiological response when they feel empathy,” said Abernathy, the Mary-Charlotte Bayles Shealy Chair in Conscientious Psychology. This empathy is measured through electro dermal activity, similar to a lie detector test.

She performed a study on individuals who scored high on the Machiavellian scale and the results were clear: The higher the Machiavellian score, the less empathetic the response.

In this research project – one of approximately 20 that she conducts at any given time – individuals were randomly assigned to watch one of three video clips. These videos, selected because they almost universally strike a chord of empathy, included five minutes of babies crying, a bullying scenario and a heartbreaking scene from “Legends of the Fall” in which one brother dies in the other’s arms.

Although the individuals reported feeling empathy, their skin and physiological responses showed no change. According to Abernathy, this could be due in part to false reporting by the subject to improve his or her image. She doubts it, because Machiavellians don’t usually care too much about others’ opinions of them. Or it could be that Machiavellians don’t know what true empathy feels like.

Abernathy, who teaches personality courses, says that although Machiavellians are known to be high in manipulation and neuroticism, they have positive qualities as well.

“They get things done,” she said. “They’re very goal-driven.”

This study, published in Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, is inspiring another study to test for conscientiousness in Machiavellian personalities.

Biofeedback is one way Dr. Amber Abernathy can prove that mindfulness has physiological effects. Photo by Kevin White

What’s your social status?

“How do you get on top?” asked Abernathy, who has published numerous peer-reviewed studies on dominance.

She’s talking about perceived popularity. Females use relational aggression, like “gossiping and backstabbing, where males might use physical aggression,” she said.

In another study published in Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, she administered a survey to a group of adolescents to determine dominance. After that, the participants played a reward allocation game in order to study how their personalities would affect their physical bodies. She pre-tested each individual’s saliva for cortisol, a stress hormone, then continued to test it at regular increments.

“The dominant female would get more stressed out at the beginning of the game. Not because of the game, but before the game,” she said. “Mid-game, the girl would realize, ‘I got this,’ and her cortisol would decrease.”

She noted that the reactions from males in the scenario were completely opposite. What was novel, though, was that Abernathy discovered a correlation between the social positioning and stress level of the individuals that caused them to respond differently.

Increasing conscientiousness

The big five

- Openess

- Conscientiousness

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

Her overarching research goal is to increase people’s conscientiousness, which is one of the big five personality traits in psychology. But she doesn’t want to just look at what conscientiousness is related to. She “actually wants to help people to work to change their personalities.”

This is a controversial topic, according to Dr. Jennifer Byrd-Craven, who served as Abernathy’s advisor at Oklahoma State University. Byrd-Craven sees personality as stable across the lifespan, while another of Abernathy’s research projects revealed that through structured goal-setting, participants increased conscientiousness (thus changing their personalities).

Byrd-Craven, who has also served as a co-author on several publications, supports Abernathy’s work wholly.

“I have no doubt that she will make significant contributions to our understanding of how personality and biological factors are related to leadership and overall health.”

Dr. Norm Shealy, neurosurgeon and chronic pain specialist, develops studies with Dr. Amber Abernathy. Photo by Kevin White

Connecting the physical and emotional

Abernathy likes to connect the dots between the physical and the emotional. She recently completed a study in which individuals made intentional choices toward becoming more conscientious for five weeks, and results showed improvements in health and energy level.

“If you are organized, responsible, neat, tidy, prepared,” which is indicative of conscientiousness, she said, that can reduce stress. This could account for some health benefits, like relieving tension headaches.

But conscientious people also, “tend to be better at health practices,” like brushing teeth, regular doctor visits, taking medicine, and drinking herbal tea, she says as she stirs her cup.

“Basically, your life view of how things are going can overcome what you’re actually physically feeling” — Dr. Amber Abernathy

Dr. Norm Shealy agrees. He’s the developer of the TENS Unit (predominately used for nerve related pain conditions), a world-renowned neurosurgeon and chronic pain specialist who has narrowed his focus to holistic practices.

“Conscientiousness is the single critical personality trait for optimal health, longevity and income,” said Shealy.

Shealy maintains that 80 percent of disease is the result of lack of responsibility for healthy lifestyle. Because of this connection between conscientiousness and health, Shealy established – in his late wife’s honor – the endowed chair Abernathy now holds.

“Amber is a ball of fire,” Shealy added. “Hopefully Amber will develop tools to help everyone become more conscientious.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Risky business: The future of football in the United States

If you said yes, Dr. Pam Sailors encourages you to reconsider.

“Kids start playing football as soon as their little necks can support the helmets on top of their heads,” Sailors said. “By the time they are old enough to make the choice to play, a lot of the damage has already been done.”

Professional and college football is one of the most-watched dramas in the U.S., but it’s become known as a risky activity.

“I’m torn about this. It’s kind of like ignorance is bliss in many ways. It’s hard for me not to watch football, but I feel kind of scuzzy about it if I do because it’s like watching people in a fight club or something. Because you know they’re hurting one another and you’re taking some sort of pleasure in it.” — Dr. Pam Sailors

Sailors, associate dean of the College of Humanities and Public Affairs, focuses her research on philosophy of sport. She reviews previously published pieces, then adds her own ideas to the discussion.

She’s written more than 60 papers, presented at about 50 conferences and appeared as an expert source in more than a dozen media publications.

Sailors published Personal Foul: An Evaluation of the Moral Status of Football in 2015. The paper was the first to use philosophical argument to challenge the ethical acceptability of football, both amateur and professional.

“Pam’s research is novel and makes not only an important contribution to the literature, but is also applicable to real-life scenarios,” said Dr. Charlene Weaving, an associate professor at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia. “She has an ability to make ethics come alive.”

Players pay the price later in life

Dr. Pamela Sailors contributed a chapter, entitled Borderline Cases: Crossfit, Tough Mudder and Spartan Race, to this 2016 book, “Defining Sport: Conceptions and Borderlines.”

Playing football is ethically problematic for three reasons, Sailors said: the likelihood of brain damage, objectification of players and a culture that entitles players to free passes for some social offenses.

When it comes to the likelihood of suffering brain damage, Sailors specifically referenced chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, or brain deformation caused by repeated subconcussive blows to the head.

“We know now that smoking causes health problems. We don’t let kids do it,” she said. “We don’t even say, ‘We’ll just let them smoke a little bit until they’re 18, and then they can choose.’”

Sailors cited one National Football League, or NFL, survey that showed almost half of retirees said they suffered from severe pain as a result of playing. The game’s head injury risk could affect its popularity.

“We still have boxing, but it’s not as popular as it once was,” she said. “I think football may be on a similar track unless there are some radical changes. The changes might be so radical that we wouldn’t even think it was football anymore.”

Why make millions when others make billions?

Football players should be paid appropriately for taking on those health risks, Sailors said, but that isn’t happening in the NFL or university teams. She cited a 2013 report which stated the top 10 NCAA football programs banked more than million and did not pay their athletes.

“I know professional football players make what seems like a lot of money, but compared to what the owners make, and the number of years they make it, they don’t,” Sailors said.

“College players are not supposed to make money. I think there’s just a huge profit being made on the backs of people who are the ones who are having the bad health consequences, but they’re not getting their fair share of the profits.”

A culture of acceptance, no matter the offense

Finally, there’s the issue of players seemingly getting free passes for bad behavior off the field. Sailors described it as a problem with football culture, exemplified most recently by Oklahoma running back Joe Mixon.

He was a first-round draft talent whose stock fell after video surfaced of him hitting a woman in a restaurant. The Cincinnati Bengals still drafted Mixon in the second round and will give him an opportunity anyway.

Sailors noted in “Personal Foul” that a culture of violence and “idealized masculinity” contributes to such behavior, especially against women.

These issues are not unique to football, she said. But here’s what is.

“Other sports have brain injury trauma problems, take advantage of players for profit and have a culture of entitlement,” Sailors said. “But what makes football unique is it’s got all three.”

The next step in Sailors’ project is determining what this means for spectators and fans of the game.

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Main photo by Bob Linder

Further reading

Trouble under the surface

It’s abundant: Approximately 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, and 96.5 percent of it is in the oceans.

The other 3.5 percent of the water supply fills lakes, streams, ponds and aquifers; forms icecaps and glaciers; and evaporates or exists inside lifeforms — like us.

For a resource that is so in-demand, it’s important to consider how long it will remain.

The other 3.5 percent

No one really knows how long the water supply will last, according to Dr. Melida Gutierrez, professor of geology at Missouri State University. It’s a question she gets asked frequently as she presents at international conferences about water contamination and the sustainability of the

water supply.

Though the quantity is a concern for the environment and farming, Gutierrez is most focused on the quality of this valuable resource. She conducts environmental studies to determine levels of contaminants and to help prevent contamination from certain waste.

For her two primary projects, she’s selected two areas she calls home: southwest Missouri and Chihuahua, Mexico.

Arsenic in water

The river Gutierrez studies in northern Mexico, Rio Conchos, was said to contain high levels of arsenic, and it was feared that the river was contaminating the groundwater supply.

She collaborated with her colleagues from the University of Chihuahua, who went to the wells and collected hundreds of water samples. It’s not as simple as dipping a test tube in a river or well, though. The team works for months calibrating the sampling containers and instruments and meeting with the local farmers to explain the process and gain approval and access to the wells.

The sampling and initial analysis must be completed quickly since the samples are reliable for no more than three weeks. These data and GPS information were then sent to Gutierrez who spent months analyzing and interpreting.

“Actually, global warming is bringing more rains to the area (in Mexico) and so it’s increasing the recharge. Everyone was so worried that there was going to be less water – the drought was going to be more intense. For that particular region, for the past 10 years they have had more rain.” — Dr. Melida Gutierrez

Contaminants were revealed in the samples, though not to the toxic level that had been previously described and feared.

To get to the heart of the matter, Gutierrez secured several faculty research grants to obtain data from the Mexican Geological Survey. Then, she worked with Dr. Daniel Nunez from the Advanced Materials Research Center (CIMAV) in Durango, Mexico, to build a comprehensive view of the landscape near the river. Nunez programmed elevation, vegetation, bodies of water and other information about the area into the geographical information system, known as GIS.

From that, Gutierrez extracted information like possible relationships between the land and water.

“I started looking at the river and how it changes quality downstream. Then I thought about the sediment, so I tested that,” she said. “It’s a trick of chemistry to know what to sample. The sediment traps the contaminants. By looking at the sediment, you have the history of contamination.”

So her investigation of the water led to further research, with each study taking months to complete.

“The same research is going to take you to areas that are connected that are not well understood. You never know where it’s going to take you next,” she said.

After sampling and testing the sediments, they began seeing the interconnection with the groundwater and began a round of tests with the groundwater.

In this case, Gutierrez found the cause of the contamination was natural. The aquifers — rock formations that store water — contained some volcanic glass that was weathering in the water, causing the groundwater to be contaminated.

“That’s part of being a scientist — that you see an interconnection — things that you might think are very separate,” she said. “All of a sudden you find that one causes the other one or they’re interconnected somehow.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Getting the message across

To extend the reach of her research, Gutierrez publishes the results in a multitude of ways, from top-tier academic journals in English and Spanish — many of her collaborators don’t speak English — to more accessible publications, like farming magazines.

Dr. Maria Teresa Alarcon Herrera, director of advanced materials investigation at CIMAV-Durango, has been a co-author on many of her latest articles. More than a decade ago, the two connected at a conference in Delicias, Mexico, where they realized their interests aligned.

“This is an urgent matter to address as underground water is the main source of drinking water in the north of Mexico,” said Alarcon.

Gutierrez has published more than 30 articles in the last 10 years. Her work has had an impact, and it is being referenced to teach the public sustainable ways to use groundwater.

“You want your system to be sustainable. Fluctuations are normal, but if they just go down, that’s not sustainable. That means you’re going to end up having no water or very bad quality water because as you go deeper and deeper there’s more and more salty water,” said Gutierrez.

How is there salty water underground? She explains that approximately 95 million years ago, the state of Chihuahua was an ocean. This history led to the salinity in the soil, which can kill plants and effectively destroy the productivity of the soil.

The flow of information

The flow of information isn’t as free in Mexico, Gutierrez noted, and she sees it causing a severe lack of trust. In fact, she thinks the water agencies have a lot of work to do on becoming transparent.

“Some colleagues who work for the government must report only things the government wants to hear,” Gutierrez said, but she doesn’t have that restriction. “I tell the people that water is a system where there are entries and withdrawals, so it all depends on your actions.”

Since the people of Chihuahua depend completely upon groundwater for drinking, they’re obviously concerned about the dropping reserve. Because of this, Gutierrez said, many take more water than they need as a precaution. This perpetuates the problem.

“It’s like going to a doctor and the doctor doesn’t tell you what you have,” she said. “You’re feeling bad, then you start fearing the worst. That’s how the farmers are: They are fearing the worst and making it come true.”

The water table is dropping, according to Gutierrez’s colleagues, but there is not a system in place for monitoring wells. Gutierrez has been encouraging the community to rise up and demand monitors so they can understand the relationship between what they take and what is available.

“What we have in Missouri, for example, we have monitoring wells. I can go online and check what the level is and what it was last month and compare it to last year. The information is available to everyone, and it’s free. Over there, they don’t have that,” she said.

She’s a geochemist with an environmental bend, and she envisions her role as an educator extends far beyond the classroom. She provides access to valid information in order to ensure more environmentally sound decisions are made at the individual and global level.

“Show them what to look for — this is science,” she said. “We do facts, so that others can apply that and make the best decision.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

A dirty job to find clarity

Gutierrez, who’s been at Missouri State for approximately 23 years, involves her students in her research, but can’t take them to Mexico to do the hands-on water sample collections due to the expense and safety concerns. That’s why she gets them involved in her sediment collection and studies in Aurora, Missouri.

The students collected hundreds of pounds of sediment and laid the samples on laboratory work tables to air dry. Next, they sieved the samples to remove all particles larger than two millimeters. Then they bagged the sediment — five grams at a time — and shipped the samples to a commercial lab in Reno, Nevada, for initial analysis.

From there, Gutierrez used these data to determine the chemistry of the water.

“I was in college in the 1970s and the environment was the big issue, so I really wanted to do something.” — Dr. Melida Gutierrez

Instead of fearing arsenic as in Mexico, they were testing for zinc — in part due to the history of zinc and lead mining in Missouri. Though zinc is regularly found, it is extremely toxic when paired with cadmium, another heavy metal sometimes associated with mining waste. In fact, it can destroy many aquatic habitats.

“You go there and physically you see no signs of former mining. Everything is clean, leveled and healthy-looking,” she said. “Going to a stream setting is going to tell you if there’s still contamination or not.”

After collecting more than 200 different sediment samples — it’s never enough, she noted — and mapping the area, she worked with Dr. Sho-Sheng “Derek” Wu, geospatial information technician at Missouri State, on the GIS.

The team then tested the groundwater and found a very limited area where contamination existed. More investigation would be beneficial, Gutierrez noted.

“We have one sample with a lot of zinc right next to one that has very little, so you want to make sure,” she said. “By taking more samples, by knowing the area, by knowing what affects the area and knowing which medium to sample, you get as close to undeniable evidence as you can.”

Since Missouri is known for its abundance of outdoor activities like hiking, fishing, canoeing and camping, Gutierrez routinely highlights the effects on natural habitats or outdoor resources in order to elevate her students’ interests in chemistry.

And she is quite proud of the ownership her undergraduate students take when they are out in the field.

Jameelah Rodriguez, an Army veteran who is an undergraduate student in the geology department, quickly picked up the tactics of collecting samples, reading the maps and setting sights on the next location. To Gutierrez, who wants to make a difference, watching Rodriguez take a leadership role on the site was gratifying.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Better together

In addition to placing a great emphasis on expanding her students’ opportunities, Gutierrez is an advocate for the power of collaboration.

This value is added when she completes projects with students, colleagues in her department, scientists at other universities and even her husband, Dr. Kevin Mickus, distinguished professor of geology at Missouri State.

Gutierrez and Mickus published an article in Science of the Total Environment. It was an overview of the presence of lead-zinc wastes around the world and the problems associated with this waste being exposed to the elements. It was the first review-paper published addressing this particular type of mining wastes.

She noted that for this project in particular, his knowledge about metals that naturally occur across the globe was extremely helpful.

Gutierrez added, “You work on something different. Everyone looks at it from a different perspective, so you get better.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Sustaining local agriculture for economic growth

Their work and stories intrigued him, ignited his passion for agriculture and led him to study agricultural economics in the United States, which changed the course of his career.

“Agriculture brought me to real people and their problems,” said Rimal, a professor of agriculture and interim department head of agribusiness, education and communication in the Darr College of Agriculture at Missouri State University.

His research interest is in applying economic theory in the food industry from both production and consumption perspectives. His accounting and finance background is an asset as he works to advance agriculture and economic growth in Missouri.

“In recent years, I’ve been working on the area of locally grown produce,” said Rimal, who has received more than $700,000 in external grant awards for his research.

An aerial shot of Millsap Farms, a family-owned 20-acre farm in Springfield, Missouri. Photo by Bob Linder

Establishing a food hub

His latest project impacts farmers directly as he explored how to get produce from a farmer’s field into a consumer’s hands more efficiently by studying the feasibility of setting up a food hub – a marketplace that connects farmers (producers) with professional food buyers, such as schools and grocery stores, and end consumers – in southcentral Missouri.

Funded by the United States Department of Agriculture Rural Development program, the project took more than a year to complete as Rimal and his team of two graduate assistants, Jennifer Muzinie and Jennifer Moldovan, interviewed 163 producers and 101 buyers in the region.

“There’s a national recognition of supporting food hubs as they can really help rural development because a lot of producers are in the rural area and they have challenges marketing their product,” said Rimal. “We wanted to see whether a food hub will stimulate the economy in this area, whether buyers are willing to buy from it and producers are willing to supply to it.”

Participants of the community-supported agriculture program at Millsap Farms select produce. Photo by Bob Linder

What do producers and buyers want?

So is a food hub feasible in this region? Absolutely, according to the findings of Rimal’s study.

“There’s a huge demand for locally produced food and buyers are willing to buy locally grown vegetables and livestock products and pay a premium for them as long as producers comply with certain requirements, such as food safety, consistency in delivery and traceability,” said Rimal.

As for the producers, the majority of them expressed interest in selling through a food hub. Of course there are challenges, such as investment of time and money to comply with buyers’ requirements or use more technology for year-round yield, Rimal noted, but he believes the benefits of a food hub outweigh the costs.

The benefits

For farmers, a food hub means less waste, greater productivity, assurance of sales and time savings.

“They don’t have to sit at a farmers market the whole day and spend their time marketing as somebody else is doing that for them,” said Rimal.

For consumers, a food hub offers easier access to a larger variety of fresh healthy foods all year long and the opportunity to support local and regional food systems. This means they contribute to environmental sustainability.

“We don’t have to eat produce that’s coming from thousands of miles away from another country,” said Rimal. “We can help improve the lives of local farmers and decrease our own carbon footprint.”

Farmers harvest produce at Millsap Farms. Photo by Bob Linder

Moving forward

He and his team have presented this research not only in the United States but also in Europe at the International Food and Agribusiness Management Association World Conference 2016 in Aarhus, Denmark.

“I’m excited about using my knowledge and technical skills in an area where it really matters. This kind of stuff has real meaning for people at the grassroots level. It can impact people’s lives.” — Dr. Arbindra Rimal

Moldovan, who interviewed a lot of the buyers, presented her part of the research at the conference. She said working on the project was a learning experience as she did not know much about food hubs going in.

“Probably the most interesting thing we found through our data was the overall acceptance of local because sometimes you don’t think bigger companies and institutions even really care,” said Moldovan. “But doing the research, we found out the different ways they are trying to support local even if they are not able to purchase because of all the regulations.”

Based on the positive findings from the study, Rimal said he is ready to continue working on making the food hub a reality. He has asked the USDA Rural Development program to fund the next part of the research, which involves developing a detailed business plan.

“I’m excited about using my knowledge and technical skills in an area where it really matters,” he said. This kind of stuff has real meaning for people at the grassroots level. It can impact people’s lives.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Protein packs a powerful punch in studies of cell processes

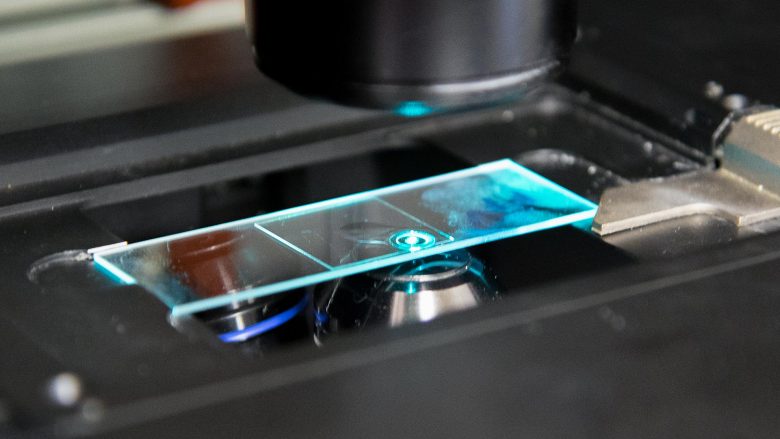

As a biology professor, Kim is interested in studying cellular processes that have the potential to one day better explain disease progression. Dynamin is a tie that binds his four studies together.

Internal recycling

In the body, some plasma membrane proteins are internalized via small sack-like vesicles formed at the plasma membrane. Then, they’re delivered to internal membrane-bound organelles prior to exiting these organelles again until the proteins are degraded. This is biomolecule recycling, one interest of Kim’s.

Using budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as his model due to its two-hour reproductive cycle, Kim has been studying how this recycling is affected by fat change, like with cholesterol. In one study, he changed the fat levels and noted that proteins were no longer internalizing, and therefore, not recycling.

“Then we deduced, ‘Oh, this increased level of fat caused a defect in the recycling process of this biomolecule,’” said Kim.

This conclusion has led him to further studies to identify which genes and molecules are actually involved in that process.

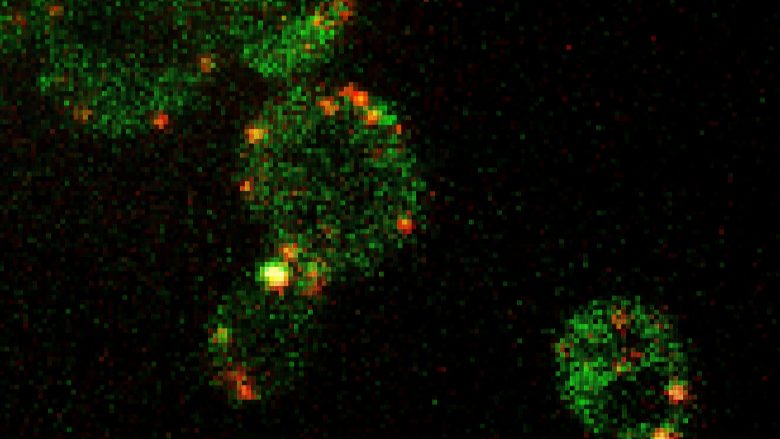

Kim uses a confocal microscope – purchased with grant funding from the National Science Foundation – and fireflies to see these tiny proteins.

Building blocks

Like humans, cells have to eat and drink in order to stay alive and active; this cellular eating process is called endocytosis. The goods are delivered to the lysosome, or cell’s stomach, and are degraded into building blocks like sugars, amino acids and fatty acids. Those nutrients eventually assist with the building of cells.

Kim notes that more than 500 proteins are serving as “work horses,” working in tandem for the efficiency of endocytosis. One of those proteins is dynamin (VPS1), which Kim discovered is implicated in pinching up the vesicles during endocytosis.

But dynamin, like the root of the word suggests, is a powerful thing. It has the ability to play many roles in the body.

“Dynamin consists of multiple domains or parts. Proteins have multiple parts, like humans have heads, legs, feet and hands,” said Kim. So he and his students are trying to identify whether it’s the proverbial head or foot of dynamin that is playing these roles.

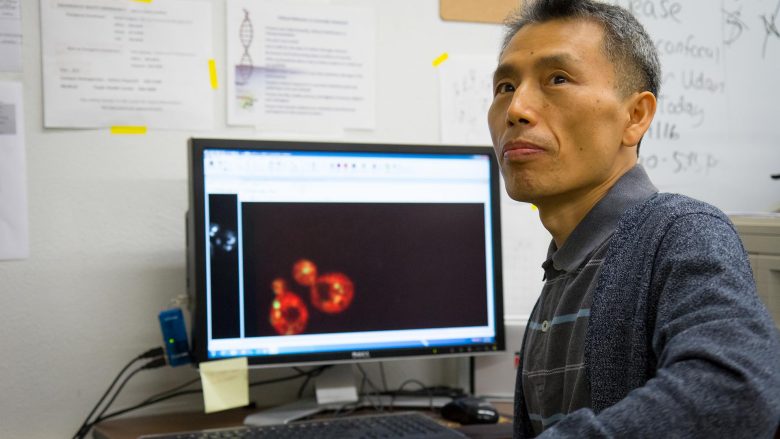

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Traffic studies

Dynamin is also involved in his third study – a study of the traffic in the body.

“Inside your body, cells are what’s considered a mega city, probably bigger than mega city when you compare it to human society. Within the cell we have a lot of stations, like membrane bound organelles,” said Kim.

He explains that there are round-trip traffic pathways between the hundreds of stations.

“If you have a cell that was expressing or harboring some mutant form of police officer regulating traffic, what happens? Pandemonium,” he said, noting that in this example, the police officer would be a protein. “If your cell is expressing a mutant form of traffic protein, such as dynamin, then maybe you actually end up with Alzheimer’s disease.”

As in his other studies, Kim is wanting to identify which part of the dynamin is responsible for this change. Though his study is of yeast, he knows that his findings could be built upon and inspire a major medical breakthrough.

“In his research he studies these events in yeast, which is an ideal model organism to study how our own cells move molecules,” said Dr. Paul Durham, director of Missouri State’s Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences and distinguished professor of biology. “His findings have implications for understanding several human disease processes including several neurological diseases.”

Another interest for Kim is the possible toxic effect of nanomaterials and the affect they may have on human cell growth. To study this, he’s been using a technique called cell culture and measuring the densities of cells. If the nanomaterials are toxic, a cell will not grow. He’s also been collaborating on several research projects looking at carbon nanotubes as well as silver and cadmium.

Connections

“Basically all four topics are all connected. In order for protein biomolecules to be internalized during recycling, cells have to use the method called endocytosis,” said Kim. “Then, the delivery between the cell’s stomach and the shipping and handling place requires traffic. Nanomaterials not only exist outside of the cell but also they can be internalized into the cell and targeted to specific organelles which they negatively affect.”

Kim’s research – much of which has been produced in conjunction with undergraduate and graduate students at Missouri State – has been published in journals like Journal of Cell Biology, Journal of Nanotechnology, Journal of Bioscience, International Journal of Science and Technology, Nanoscience and Nanotechnology and Biochemistry and Cell Biology.

In addition to Kim’s exemplary research program in cell biology, Kim was honored with the 2015-16 Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Teaching. This award is only given to one faculty member from each of the state’s public universities.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Inspiring people to action through informed design

Graphic designers are charged with delivering those messages in an effective way. Do it wrong, and there may be unintended consequences.

“If I design a sign which tell you, ‘Turn right,’ but actually you need to turn left, you can kill yourself!”

That’s Cedomir Kostovic, a professor in the department of art and design.

He came to the U.S. in 1990 from Bosnia and Herzegovina and has been teaching graphic design at Missouri State University for 25 years.

“If I design a sign which tell you, ‘Turn right,’ but actually you need to turn left, you can kill yourself!” — Cedomir Kostovic

Design, Kostovic said, is about using visual communication to solicit a desired human behavior.

From public service posters and commercial advertisements to road signs, designers must think beyond artistic expression to understand how color, typography, imagery and other content can be leveraged to create a design solution.

They must also use this power responsibly and for the good of society, he said, a mentality he adopted from his college professor and mentor, Mladen Kolobaric, at the Academy of Fine Arts Sarajevo.

“He always have us design posters for social issues. I remember thinking, ‘Why he bother us with that? I want to design poster for rock band.’ But out of this I really figured out visual language is so powerful. This is when I fell in love with design.”

Remembering his roots

Kostovic now inspires his own students to do the same, both in the classroom and out.

An award-winning designer, Kostovic’s socially impactful posters are known throughout the world. His recent sabbatical project, an international poster exhibition, reached thousands of people across five countries.

“I usually call my students ‘little kiddies’ who come blind to my classes, and when they come out of classes, they can see. Everyone that sees can be tomorrow’s inspiration for ideas.” — Cedomir Kostovic

He organized the exhibit with other former Kolobaric students: Amra Zulfikarpasic, Dalida Karic-Hadziahmetovic and Mila Melank.

In 2014, the quartet challenged hundreds of designers around the world, including 30 Missouri State students, to commemorate the last 100 years of history for Kostovic’s native city, Sarajevo, a place where cultures converge and, sometimes, clash.

It has seen years of war, starting with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 that sparked World War I, and more recently the siege and ethnic genocide during the Bosnian Conflict.

“I remember when I have interview at Missouri State in ’92, this was the day officials start war (in Sarajevo),” Kostovic said. “I remember finishing interview, I go to my room and turn on TV. It was showing these people running away and snipers killing … It was horrible!”

The embattled city has also striven for peace and unity, punctuated by its hosting of the 1984 Winter Olympics, the first winter games to be held in a Communist state.

Celebrating resilience, hope

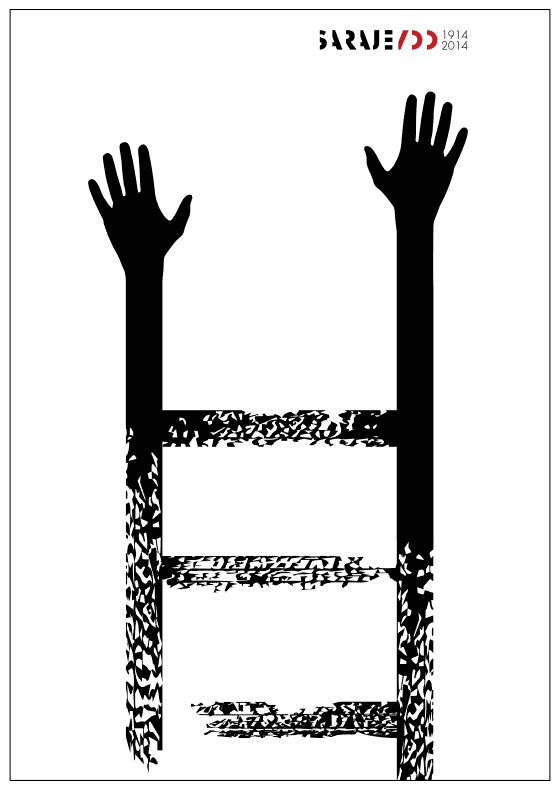

Design by Cedomir Kostovic

“Sarajevo 100” debuted in June 17, 2014, at the City Gallery Collegium Artisticum in Sarajevo, showcasing the work of 268 designers from 37 countries and five continents. The project was supported by the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo.

The posters offered a diverse, multicultural perspective about a place many of the participants had never heard of before.

MSU alumnus Tyler Galloway, now chairperson of the graphic design program at Kansas City Art Institute, participated in the exhibition. His poster paid tribute to his teacher, Kostovic, and his teacher’s teacher, Kolobaric.

“I wanted to give a sense of that generational influence and a sense of location for each generation — stretching from Sarajevo to Springfield to Kansas City,” Galloway said. “I’m very fortunate to have kept in touch with Cedo over the years and to benefit from his wisdom and advice as an educator and designer.”

The exhibit traveled to France, Russia, Mexico, Poland and Missouri State University’s Springfield campus, bringing global attention to the region, its history and its growing recognition as a symbol of peace.

Kostovic said the posters will likely be studied by designers for decades to come; and his own poster will be among them.

On it, a black, partially burned ladder appears against a stark white background, its three rungs leading to two hands reaching upwards.

The three steps symbolize the three historic events — Ferdinand’s assassination, the 1984 Winter Olympics and the 1990s Bosnian Conflict — as well as the area’s three ethnic groups — Serbs, Croats and Muslims — who, despite years of conflict, still have hope for peace.

He explained: “You see all this (part of the ladder) is a little distressed. A lot of pain is there. Still, there’s hands reaching out of that, and the future, hopefully, will be better.”

- Story by Trysta Herzog

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

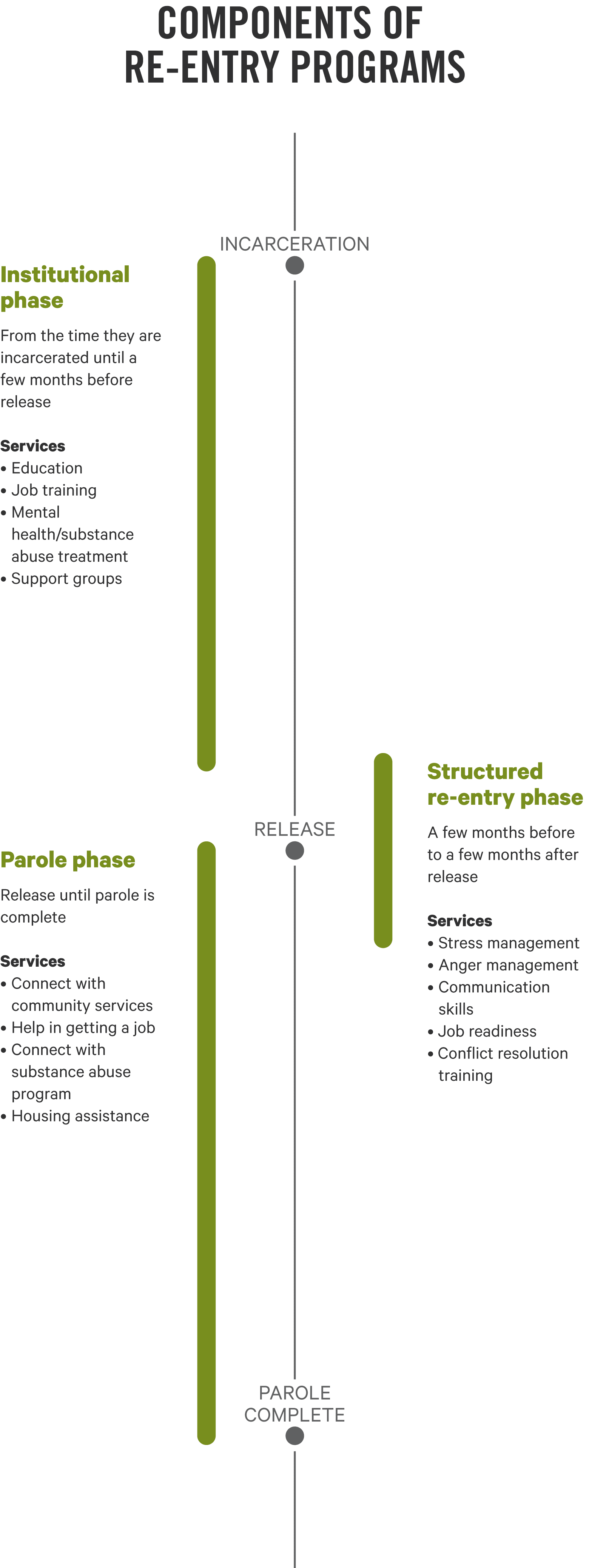

Keeping parolees out of jail

Dr. Brett Garland, head of the department of criminology and criminal justice at Missouri State University, has been studying the criminal justice system for over a dozen years. He’s published more than 40 journal articles, book chapters and other scholarly works, mostly on topics pertaining to correctional issues.

One primary area of research for Garland is prisoner re-entry. That’s the phase from a few months before a prisoner is released to a few months after release.

“That’s the time period where offenders are really starting to transition mentally; they’re getting themselves ready for the release,” he said.

Which is better? The carrot or the stick?

A study Garland did with co-authors Dr. Eric Wodahl and Dr. Scott Culhane from the University of Wyoming and Dr. William McCarty from the University of Illinois at Chicago found that offenders are most successful in following the terms of their parole when a combination of sanctions and rewards are used.

“We know from psychology and from behavioral learning theory that rewarding people for things they do right is even more important than punishing people for something they do wrong. Our study confirmed that this principle holds true for criminal offenders,” said Garland. “In the last decade or so, there’s been renewed attention to incorporating incentives and using a true behavioral model when monitoring people who are on probation and parole.”

Garland has collaborated with Wodahl on a number of projects. Wodahl is a former probation and parole officer and said he thinks this research can help supervision officers do their jobs more effectively.

“I believe this research has the capacity to help lessen our reliance on prison in this country,” he said. “A large portion of prison inmates are incarcerated for violating the conditions of their probation or parole supervision. The use of sanctions and incentives has been shown to lead to fewer revocations and fewer people being sentenced to prison.”

Garland said to gain maximum compliance from a probationer or a parolee, officers must be committed to utilizing reinforcements whenever suitable opportunities arise.

Time off is best incentive

Another study by Garland and Wodahl, in Colorado, examined the value that offenders ascribe to various types of incentives relevant to probation.

The researchers interviewed 200 offenders and presented 16 options, including monetary incentives, reductions in supervision time and travel opportunities, among others.

“The perceived effect from the offender’s standpoint was that getting time off of a sentence was more important to them and therefore more valuable than all other options,” said Garland. “The policy implication here is that you don’t necessarily have to spend a lot of money to provide good incentives for offenders.”

As the cost to incarcerate a person continues to increase, finding ways to keep people out of prison may be the best solution. Garland hopes his work will help do just that.

- Story by Andrea Mostyn

- Photo by Kevin White

Further reading

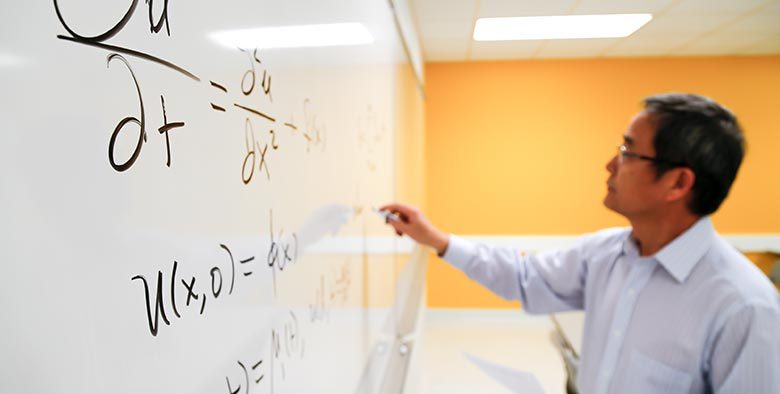

Prove it: Math makes the world go ‘round

Enter mathematics

Mathematically, such laws are expressed through differential equations or, more generally, dynamical systems.

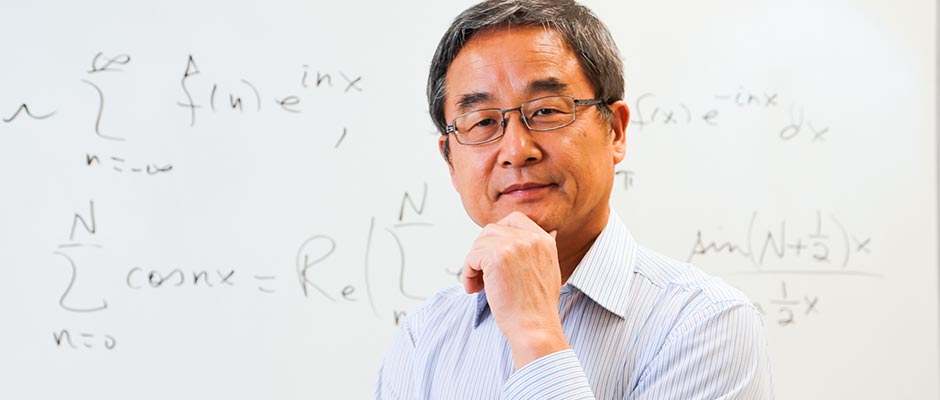

Dr. Shouchuan Hu, professor of mathematics at Missouri State University, has devoted his career to the study of differential equations, dynamical systems and nonlinear analysis. This area of mathematics largely asks theoretical questions. More often than not, it is impossible to write down the explicit solution of the differential equations that describe physical processes.

“Often in mathematics we’ve been taught to say that graphics will show you or give you some intuition and ideas, but they will never serve as a proof.” — Dr. Shouchuan Hu

Therefore, Hu and others in this field investigate whether or not solutions exist. If a solution exists, the mathematician determines if the solution is unique and under what conditions and studies the qualitative behavior of the solution — a topic that often relates back to behavior of physical systems.

As an example, think about planetary motion.

“Certainly if you look at the planet orbits, they are periodic,” said Hu. “Such motions can be governed by a common differential equation, and sometimes a solution of such an equation is exactly the orbit of this motion.”

The ideas and methods used to study the differential equations of planetary motion can be applied to biological questions, like whether an animal species population could be periodic or environmental conditions such as seasonal weather changes.

Collaborative nature of math

One of Hu’s long-term collaborators is Dr. Nikolaos Papageorgiou, professor of mathematics at National Technical University in Athens, Greece. Together they produced two textbook volumes on multivalued analysis – a subfield of nonlinear analysis – that has been praised for its exhaustive depth in the field.

Papageorgiou is excited by the number of non-mathematicians who benefit from their work.

“Almost all interesting problems in nature and society are highly nonlinear and the traditional tools of classical linear functional analysis do not suffice to tackle them,” said Papageorgiou. “Today, many nonmathematical disciplines use the notions, techniques and theories of nonlinear analysis to come up with more realistic models of the phenomena they study and to analyze them.”

Mathematically on the map

When Hu came to Missouri State in 1987, he was the first professor from mainland China to join the faculty, and he quickly made a name for himself in his field. In 1995, he helped launch the international journal Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems and has served as the editor-in-chief ever since. He also serves as the co-editor-in-chief for the international journal Communications on Pure and Applied Analysis.

Though it can be a time-consuming and intimidating task to produce a peer-reviewed academic journal, he is proud of the quality of contributors it attracts. Seven Fields Medal recipients have contributed papers over the years.

“The Fields Medal – it’s basically like a Nobel Prize for mathematicians. In a way it’s even more prestigious than the Nobel Prize because it’s only distributed every four years,” he said.

Photo by Bob Linder

He’s also been able to bring that level of esteem to one of his other notable achievements: In 1996, Hu was the principal organizer of an international conference on Dynamical Systems, Differential Equations and Applications and has served as the chairman for this conference since its inception.

Many Field medalists have presented their research at this biennial conference, which has grown to be the largest conference in the field. From 250 attendees in the first year, it catapulted to regularly include 1,500-2,500 attendees. This international group had its first meeting at Missouri State, and Hu said, it put the university mathematically on the map.

“It’s the largest, most attended conference in the field,” Hu said. “This conference series has become so influential, and it has fulfilled a need in the scientific and mathematic community. Everywhere you go, at least in every mathematical department, some of the faculty will know us.”

In 2000, Hu helped form, and currently directs, the American Institute in the Mathematical Sciences. AIMS is now responsible for the organization of the conference, and it publishes 14 journals in a variety of areas of the mathematical sciences, and publishes a book series related to dynamical systems and applications. To a large extent, AIMS represents Hu’s vision toward furthering mathematical research.

He has also published 76 refereed research articles – many in collaboration with Papageorgiou – in the area of differential equations and dynamical systems since becoming a faculty member at Missouri State.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Bob Linder

Further reading

Making a statement through the creative process

“I think everybody is creative to some degree, whether they’re creating artistic products or finding new ways to be an accountant or a building contractor,” said Prescott, professor of music at Missouri State University.

“Creativity is part of the human persona,” he said. “People will say, ‘Well, I’m not creative.’ They just aren’t realizing that creativity lies in a lot of directions, not just the arts.”

Prescott’s creativity led him to become a composer whose library of titles includes about 200 works. He’s also enthusiastic about world music – specifically Chinese – and has spent much time teaching students about the rudiments of playing traditional instruments.

His commitment to helping students stands out, as he also utilizes creativity when it comes to advising students. He spent a decade as music department head at Missouri State and discovered he had the opportunity to invent creative solutions to guide students toward the finish line of graduation.

Prescott has demonstrated his commitment to assist Missouri State students in general, said Samantha Sack, a senior composition student who has worked with Prescott for about three years.

“Dr. Prescott is very helpful in helping students focus, reach goals and get material to work with,” she said. “It isn’t just in composition, though. He’s very supportive of students in other areas too. He has a general passion for helping students succeed.”

Photo by Kevin White

The creative process

Writing music can be a fulfilling and humbling process, Prescott said. One key is achieving a level of equilibrium.

“Some of the pieces I’ve spent a lot of time working on have not sold well at all,” he said. “But there’s a piece in my catalog called ‘Aliens Landing (In Your Back Yard!)’ that took me about two hours to write on an airplane, and it has sold a lot of copies and been very successful for the publisher.

“It’s writing pieces like that that allow me to also publish the more serious things that I’ve spent more time at, so I have to balance those things. The commercial and the artistic have to get balanced and sometimes things lean more one way or the other.”

Photo by Kevin White

Remembering 9/11 through music

One of Prescott’s most recent compositions is a rearrangement of the four notes in “Taps.” Four students – Jacob Batey, Darrell Burton, Gabriel Duerkop and Elisa Wren – performed the piece, titled “Quadrivium,” for the first time on the 15th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks.

“Everybody who’s an artist wants to feel fulfilled like their art matters. That what they’re saying is important to somebody else.” — Dr. John Prescott

Months before the student performance, Prescott demonstrated the piece on piano in his office. “Quadrivium” places simultaneous notes in different keys, which creates a discordant sound that reflects the terror of 9/11.

“Now it’s not quite so pretty, right?” Prescott said. “There’s a bit of bite to it.”

Still, there’s beauty in uncertainty and dissonance, Sack said.

“He’s a great composer. That piece is beautiful and touching,” she said.

The choreography of the piece placed Prescott’s students at four locations in Missouri State’s Historic Quadrangle in the heart of campus. As they played, the students slowly converged at the cornerstone in the center. The piece reached its climax when all four players reached the cornerstone and played in a meaningful pattern: nine notes, then 11 notes.

The group played in four different keys at the same time.

“This is about 9/11,” Prescott said. “We don’t want this to be pretty music. We want this to be music that makes people think and creates tension.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

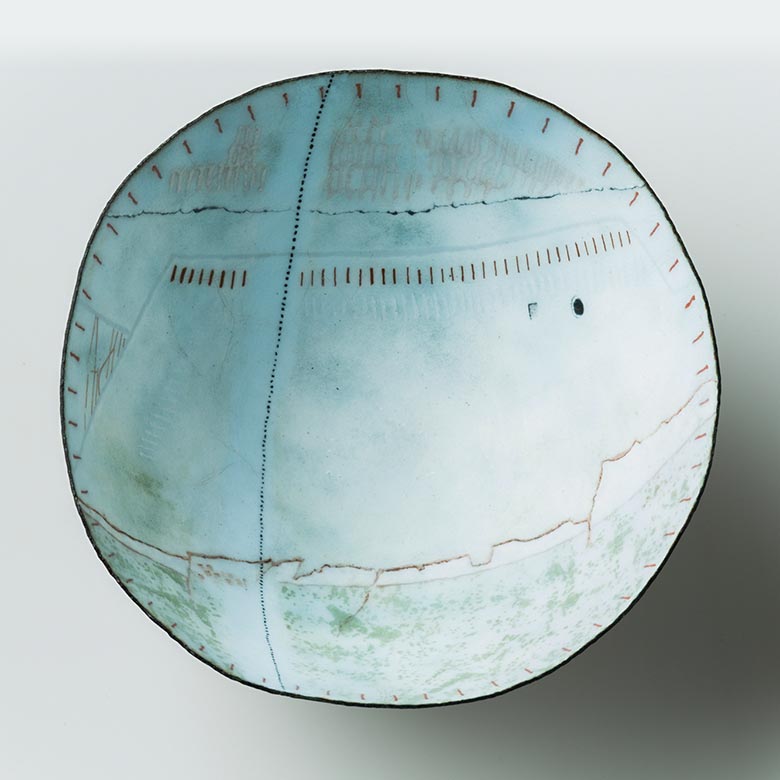

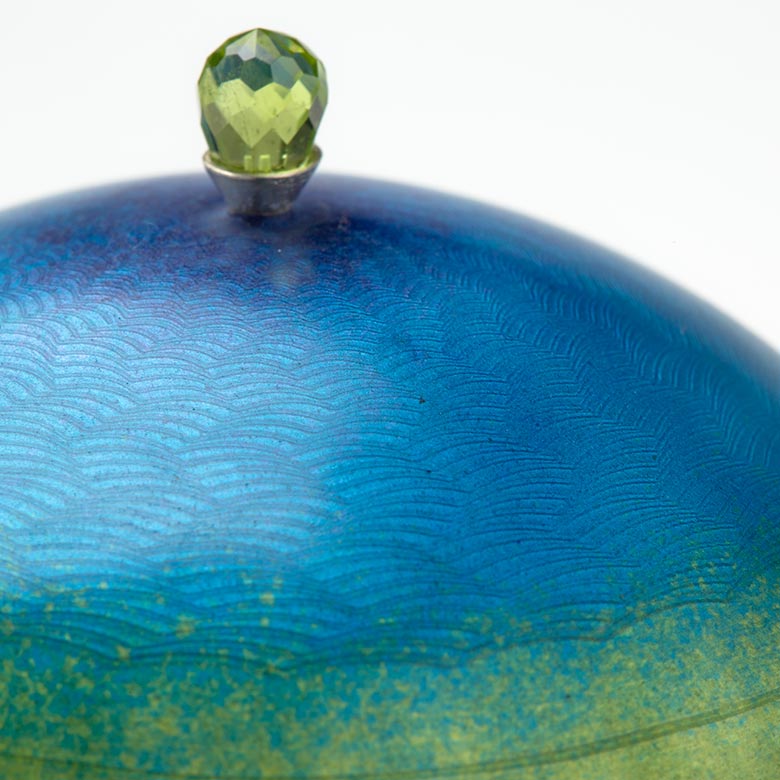

Selected works by Sarah Perkins

Walstrand Walls

This is from a series that I was doing with Gwen Walstrand, based on what we’ve seen in Cairo, Illinois. She takes pictures, and I respond to the photographs that she takes. I really like the idea of it sort of getting double translated, her interpretation of it and then my interpretation of her interpretation. I like that idea of people influencing each other. Sarah Perkins

Building photos by Gwen Walstrand • Bowl photos by Tom Davis

Perkins loves to play with texture and draws inspiration from a variety of sources. She says that for this vessel, called Gourd, she made the surface “smooth and satin like the skin of a vegetable so you’d want to touch it.”

Cactus required Perkins to hand-drill 300 holes in the body of the vessel. She then inserted wires at precise angles so they would stick out in proper proportions. She finished the piece by soldering the wires to the vessel and melting their ends.

Perkins says, “My work is changing right now, and I’m getting a much brighter color palette than I have before. I think having gone to India had a lot to do with it.”

In Roe, Perkins employed an ancient technique called ‘granulation,’ which uses chemistry, evaporation and extremely high temperatures to fuse tiny balls of metal onto a larger piece without any solder. It took her days just to place the metal balls.

“I’m interested in getting down to the formal fundamentals,” Perkins says. “Shape, texture, color and nothing else.”

Perkins looks to the natural world for textural references and combinations. About this piece, Lichen, she says, “I like for the inside and outside to be different. So the inside may be smooth and shiny, but the outside is rough and tactile.”

Perkins’ jewelry often plays with graphic, minimalist combinations. Of this piece, she says, “I like the texture of the druzy stone, which I bought as a piece, next to the texture of the enamel.”

Historical art and fashion inspire some of Perkins’ pieces — like this one, which was crafted to look like the gores of a ball gown. “I thought it looked like Cinderella’s dress,” she says.

Perkins mixed red glass seed beads in with a range of red enamels. “The beads’ melting temperature is a little higher than enamel,” she says, “so it’s got that mottled quality like moss.”

Perkins says this group of jewelry is largely “about what’s perfect placement at the moment. Maybe an hour later, I would’ve put that stone in a different place. But right then, it was very deliberately exactly there.”

Photos by Tom Davis

Transformation

But art and design professor Sarah Perkins has mastered a process that turns plain material into a shimmering work of art.

She begins with a thin sheet of metal, which she cuts and hammers into three-dimensionality. She uses fire to enhance the metal’s malleability. After many rounds of hammering, the sheet of metal has become a completed vessel.

Next, Perkins showers the vessel with powdered enamel glass before firing it in a kiln as many as 30 times. The glass melts and fuses to the metal, creating an art piece with Perkins’ creative vision.

I look at a lot of historical work and reference it. Sarah Perkins

This process, which combines metalsmithing and enameling, distinguishes her art.

“I’m unique among metalsmiths because I enamel, and unusual among enamelers because I have a background in metals,” she says.

Cabinet maker Charles Radtke, who first met Perkins in the early ’90s before going on to collaborate with her, recalls being struck by her creativity and technique.

“I was drawn to her work immediately,” he says, “most drawn to the vessels she was creating. They seemed like little mysteries to me, the movement of landscape, the subtle textures and color changes.”

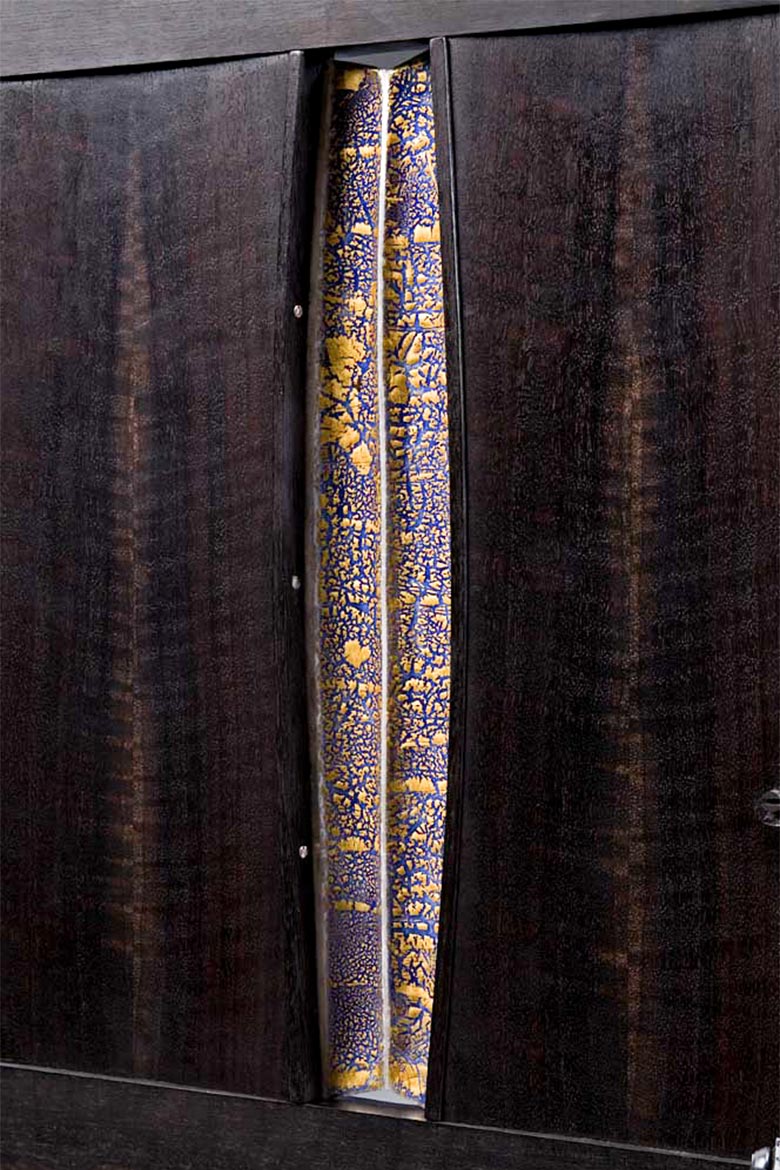

Collaboration with furniture maker Charles Radtke

Neither of us sketch, so we convey ideas and a vision that, through much talking and laughing, we come to a sense of the object. Our minds spin wild with possibilities because we know, in the end, whatever we dream up, we can surely make.

Charles Radtke

Photos by Larry Sanders

Global recognition

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”

The risks paid off, and her art has gained global recognition. She’s been the subject of solo exhibitions in Boston, Memphis, Tucson, Taipei and many other cities, and she’s slated for a solo retrospective in 2019. Her work is part of several public collections, including the Boston Museum of Fine Art, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Long Beach Art Museum and the National Ornamental Metals Museum, as well as about a dozen private collections.

A number of organizations, including the Enamelist Society, the Richmond Art Center, the Springfield Art Museum and the Midland Museum of Art and Science have honored Perkins’ work. Her history of awards recognition began in 1979 and continues to this day, in part because she still leaves room for experimentation.

“I’ve started firing dirt into the enamel to give it an interesting surface,” Perkins says. During a hiking trip to Montana, she collected sand, which she later incorporated into her enameling. “One of the sands had a lot of obsidian, which is a natural kind of glass,” she remembers, “so it actually melted a little bit.”

Travel provides visual cues as well. In India, the vibrance of traditional handicrafts inspired new color combinations and applications, and the black and white stripes Perkins observed near roadsides in Delhi emerged as a pattern in an exultant series of bowls.

Delhi Stripes series

One day riding around Delhi, India, I was struck by the patterned walls, and I started taking pictures of them. Later, as I looked at the photos, I realized, ‘That’s it. That’s my key.’ I felt like I had an entry into being able to represent what I was seeing there, and it was a completely different entry than I was expecting. Sarah Perkins

Delhi street scene by Sarah Perkins • Bowl photos by Tom Davis

A rebirth of enameling

Perkins is pleased that over the course of her career, respect for enameling has grown. She says, “In America, enameling was somewhat lost as a medium until after World War II,” when it was popularized in kitschy items, particularly ashtrays. According to Perkins, “We’ve had to push past that history of crafty trinkets,” and her innovation and advocacy have played a role in this success. “I think I’ve played a part in raising the profile of enamel,” she says.

As enameling’s stature has grown, so has its reach, which provides Perkins with opportunities to spread her artform. Through her Missouri State colleague Keith Ekstam, she connected with the Tainan National University of the Arts in Taiwan and began teaching workshops there.

I’ll have an idea of the piece, so I know basically what colors I’m going to use. But sometimes I’ll put a color down and go, “You know, I was going to put that chartreuse green there, but it’s wrong.”Sarah Perkins

“I was one of the first people – maybe the first person – to teach enameling there,” she says. “Many of my students were people who taught at other universities in Taiwan.” These instructors then began teaching Perkins’ techniques to their own students. “When I went back last spring, it had been about 13 years since I’d first been there. I learned that the enamelers there call me ‘Granny’ because I’m considered the teacher of the teachers.”

Perkins may sometimes marvel at her own evolution into a grande dame of her artform. “From an early age, I knew I wanted to be an artist and professor,” she says, “but I never told anybody because I was afraid I wouldn’t be successful. I tried to do other things until I realized I needed to just go for what I wanted.”

From those long-ago doubts to today’s accomplishments, it’s been quite the transformation.

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Developing cultural competence in tomorrow’s leaders

“Post-millennial generations are going to be incredibly visually oriented,” he said. “If we don’t captivate their interest with this type of a digital humanities project, the humanities are going to fade away into being insignificant in the public’s mindset.”

“Post-millennial generations are going to be incredibly visually oriented,” he said. “If we don’t captivate their interest with this type of a digital humanities project, the humanities are going to fade away into being insignificant in the public’s mindset.”

That’s why Chuchiak, professor of history and director of the Honors College, and Missouri State alumnus Justin Duncan are creating the Digital Auto-de-Fé, a 3-D simulated recreation of the 1601 Public General Auto-de-Fé of the Mexican Inquisition.

The project will attempt to visually and interactively portray the human experiences, pains, shame and public punishments related to these acts of religious intolerance that occurred hundreds of years ago in multiple places around the globe.

The project uses video game technology for a greater purpose: cultivating cultural competence in middle school, high school and college students in the modern age.

“We created a virtual reality simulation of the inquisition’s auto-de-fé, through the story of a young Jewish woman who was persecuted by the Mexican Inquisition, to teach empathy and religious tolerance,” Chuchiak said. “Using an avatar as either a viewer or participant in the event, you’ll feel the terror of being persecuted.”

“You’re going to see what it’s like to be a member of a restricted caste or class. That’s part of our goal: to teach empathy and racial and religious tolerance.”

The inquisition in Mexico is among Chuchiak’s main areas of study, which also include research into the Spanish military conquests against the Maya, and the study of the role of the Maya in Spanish colonial defense against European piracy.

Chuchiak’s accomplishments include four published books, two published translations of primary sources in translation, 50 published book chapters or journal articles and more than 100 international and national conference paper presentations and keynote invited lectures.

What’s an auto-de-fé?

The public “act of faith,” or auto-de-fé, was a costly public spectacle mandatorily attended by all residents of a major city. The Inquisition intended these spectacles to serve as major educational tools and deterrents to religious dissent.

The people of Mexico were required to fall in line with the teachings of the Catholic church. If they didn’t, they’d be fortunate to bear the public shame of appearing in a public auto-de-fé. The other options were far more grisly punishments for those convicted of false belief, up to and including a death sentence.

You’re going to feel it

“It’s easy to read about points in history, but when people begin to see and feel an event, history and humanities in general come alive,” said Duncan, a special education teacher at Springfield Public Schools.

The idea for this digital humanities project came to Duncan while writing his graduate thesis – under Chuchiak’s direction – of the Spanish Inquisition’s autos-de-fé of that time period. He had a difficult time explaining what the space and concepts of power involved in these events looked like in words.

Users can live the story of a young Jewish woman, Mariana Núñez de Carvajal, who watched her parents get burned alive for practicing Judaism after being forcibly converted to Catholicism. She was later burned at the stake by order of the Mexican Inquisition for the same transgression.

It’s the chance to live in a virtual world as a member of an oppressed class, a middle class, and even those in positions of power – tens of thousands more characters will be developed as options for future viewers – that will drive the point home to students.

Users will experience the sights and sounds of the terrifying event of an Inquisitorial auto-de-fé with sensory vibrations. Scornful public observers throw items at the oppressed characters, who walk dressed in the ceremonial garments of shame, known as the Sanbenitos, that the inquisitors forced them to wear.

What lies ahead

The project team includes 15 members, featuring top subject area experts from universities from the U.S. and Mexico. The group includes Missouri State faculty Vonda Yarberry and Colby Jennings, who serve as electronic arts consultants and advisers.

Digital Auto-de-Fé has expanded to the grants stage, which includes applying for funding through the National Endowment of the Humanities, National Endowment of the Arts and private foundations in the U.S. and Mexico. Just to get started, Chuchiak said, the cost will be about $300,000.

Still, the payoff could be huge.

“Students are going to see how ugly it was when religious intolerance is in play,” Chuchiak said. “We’re at the cusp of a change in the way humanities are going to be taught, and this is part of it. People should know that everyone’s views, religions and cultures are worthy of respect.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Do recent regulations help the banking industry reduce risk?

Analyzing a portion of a federal financial law

In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was signed into federal law in response to the meltdown of ’08.

Many people involved in creating that legislation looked at how companies were controlled.

“Corporate governance was under the microscope at financial institutions,” Hines said. “People wondered if one of the main reasons something went wrong was related to the way boards were functioning.”

As part of Dodd-Frank, publicly traded banks that met a list of criteria, including holding $10 billion or more in assets, were required to create a board-level “risk committee” that included independent directors.

In business terms, “risk” is any threat to profits and assets. Assets may range from cash to consumer data, intellectual property to land or equipment. For banks, assets primarily consist of loans.

Threats to assets vary, but include financial downturns, security breaches, lawsuits, accidents, natural disasters and human error.

Risk committees try to help companies identify, analyze and change any factors that could harm profitability and assets.

Hines’ research focus since 2012 has been to examine the short-term outcomes of adopting these committees.

“In my PhD dissertation, I looked at financial institutions that voluntarily formed a risk committee at their board level.”

He wanted to see if profitability and risk measures were better or worse about a year or two after the company formed the committee.

Photo by Kevin White

Becoming one of the first to examine this topic

Since Dodd-Frank was so new, Hines’ work broke fresh ground.

He has looked at several issues surrounding risk committees, including how having a committee affects auditors’ perceptions.

He and co-authors have published in peer-reviewed journals including the Journal of Accounting and Public Policy as well as Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory.

Dr. Adi Masli, a University of Kansas assistant professor who met Hines in the PhD program at the University of Arkansas, was a co-author on one paper.

“He provides great insights, and is knowledgeable about this field of research,” Masli said. “We hope to work together again on future projects.”

Photo by Kevin White

Reporting some findings, need for more research

So far, Hines said, “there really isn’t a whole lot of strong evidence that forming the risk committees affected banks’ risk or profitability in the short-term. However, there is evidence that risk committees, and the specific way they are structured, do affect auditor perceptions in the short-term. I think more research needs to be done to say anything about the long-term.”

However, “not all risk committees are created equal.”

The people who sit on the board (i.e., whether they have a large stake in the company or are more independent, and whether they have risk expertise), the questions the board asks, the ways the board reports findings and more could make a committee more or less effective.

Some industry experts, he said, contend that risk oversight should really be the responsibility of a company’s full board, even if the company has a specific risk committee.

“Researchers had not focused on risk committees in the past, so there wasn’t a lot of background for me to incorporate.” — Dr. Christopher Hines

Photo by Kevin White

Potentially contributing to new public policy

Dodd-Frank is likely to be re-examined in Washington, D.C., since new U.S. President Donald Trump has said he would like to dismantle it.

Hines holds a College of Business Endowed Research Professorship, so it’s probable he will be doing more analysis of this topic. It’s possible that his current and future work could be used by lawmakers who hope to learn about best practices as they craft public policy.

His new research will be conducted from his alma mater: He is a 1994 and 2001 Missouri State alumnus, and has worked here since 2013.

“There’s a very collegial atmosphere and supportive environment in the College of Business. Missouri State is a great place to enjoy all aspects of being a professor.”

- Story by Michelle Rose

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

Five-star service starts with a better curriculum

“When I told him I was coming back to teach at Missouri State, he said to make sure that the students understand what the industry is really about, because it is a challenging industry,” said Hein.

Hein took this advice to heart and early on was interested in how to improve her own teaching and abilities in the classroom. In 2008, she began developing a program review process with her colleagues.

Improving service through industry

Photo by Kevin White

In her article, “A Systematic Model for Program Evaluation and Curricular Transformation: A Tale from the Trenches,” Hein and her colleague, the late Carl Riegel, former professor, aimed to eliminate one of the biggest issues many programs face: curricular review.

“In the article, we discuss how we went about reviewing the program and implementing changes for improvement,” said Hein. “We also wanted to tie together what we thought was important to the curriculum with insight from industry. We felt industry input was an important piece of the process.”

“You have to be nimble to some extent and really pay attention to the demands. When I first started teaching, we had a heavy interest in support from the restaurant industry. That’s where a lot of our students went. Now, it’s shifted and it’s the servicing and lodging industry. You have to make sure that you know what’s going on in all these different segments.” — Dr. Stephanie Hein

The pair surveyed industry partners across the nation, totaling nearly 150 respondents. Their survey results provided a wealth of information that led to several more articles.

“We focused on what industry thought was important in the curriculum. There is a core body of knowledge that is commonly taught in hospitality programs across the country. We wanted to know the value industry placed on each content area that makes up that core,” said Hein. “That really is what spurred the process — making sure that what we are teaching in the classroom is relevant to what industry needs.”

They discovered that industry had five main areas of concern when hiring new employees: communication skills, ethical considerations, financial management, organizational/management theory and management of hospitality operations. Special attention was granted to these areas as the curriculum was reviewed and reworked, with an emphasis on communication, ethics and financial management.

Working together to build something better

After the article was published, the response was overwhelmingly positive. To date, it has been downloaded nearly 650 times and her presentations on the article often pack the house. It is setting the standard.

“There’s a need within academia to provide a systematic process for program review and development,” said Hein. “Because of my evaluation experience, I am often called upon to assist with external program reviews and accreditation visits at other universities. When I do an external evaluation, I focus on whether or not the program being evaluated is meeting the standards of what should be included in the curriculum, and often use our model as a guide.”

“There is this need and this curiosity of how to work this review process. I’ve given a lot of presentations at academic conferences and panel discussions, and sometimes you go in and there’s a few people in the room. With the piece on the program review, the room was packed, and we had so many people afterwards asking about this process.” — Dr. Stephanie Hein

The model has since been used to guide the hospitality leadership program itself and ensure students are receiving the highest-quality education possible. Hein believes this is reflected in the newly renovated Pummill Hall where the department is housed.

From the selection of the architects, to the design of the facility, to move in and opening day, Hein was there every step of the way and served as the project’s point person.

“The nature of the courses we teach required a more hands-on approach when it came to designing the facility,” said Hein. “I wanted to make sure the building appealed to our students. To ensure their input was captured, I held multiple focus groups to learn what was important to them.”

Collaboration was the cornerstone on which the renovations were built, and they were driven by three essential concepts that Hein kept in mind during the entire process: establish a positive learning environment, create a collaborative learning environment and enable students to be a partner in the teaching process.

“While the department made do with the resources they had previously, the newly renovated space is essential to the growth of the program,” said Kara Edwards, a student who assisted in crowdfunding efforts for the building renovations. “Students are now set up for success with not only the advanced technology, but also the space they are provided with. It was a truly rewarding experience to be a part of the crowdfunding efforts, and to see the difference it has already made in the quality of education the hospitality program is able to provide.”

All three components are reflected in the building: a stimulating color palette throughout the building creates a positive learning environment, tables instead of desks promote collaborative learning, and students being able to voice their wants and needs about the new renovations allowed them be a part of the teaching process.

“We knew we created a strong curriculum when we went through the program evaluation and transformation process. The facility now mirrors this quality and closes the loop,” said Hein. “With that being said, we are continually working to improve because if we don’t we will become obsolete. We will continue to make adjustments to ensure we are meeting both our students’ and industry’s needs.”

Hein continues to work on improving curriculum; she was recently appointed to the Accreditation Commission for Programs in Hospitality Administration (ACPHA).

According to Hein, “The commission gives the final review and approval when programs go up for either initial accreditation or re-accreditation.”

- Story by Shay Stowell

- Main photo by Kevin White

Further reading

Mirror, mirror: Self-reflections on hidden prejudice

Photo by Kevin White

Moving the needle for middle schoolers

The class – now a required course for all psychology majors – also involves presenting Diversity Pep Talks at local middle schools. Since middle schoolers are at such an impressionable age, Young-Jones and her students lead discussions and activities in hopes of teaching the children to celebrate diversity – of skin color, race, religion, weight and socioeconomic status – and build empathy. Young-Jones is proud of the program: When the university received the 2014 President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll award, these diversity workshops were cited as one of the factors. Building on the success of the pilot semester, Young-Jones is trying to find methods of tracking long-term effectiveness of the program. This would be novel since 81 percent of diversity training courses reported having no follow-up effectiveness measurement, she added.

Young-Jones, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State, believes she’s personally experienced advantages related to her ethnic-cultural background, and she’s passionate about helping students of all backgrounds achieve fulfillment and success. Her interest in students’ educational success has led to more than 20 published articles in the last 10 years on these and related topics.

Bullying and diversity are two focal areas related to student success, she noted. So, she developed curriculum for a Psychology of Diverse Populations course, which allows students to discover subconscious preferences, evaluating these subtle prejudices so that they may grow past them.

This work requires Young-Jones to lead complex, sensitive classroom discussions. She maintains civility and respect by reminding students, “You are the expert in your shoes,” and cautioning against generalizations and accusatory “you” statements.

The students also serve as a primary source for one of her long-term research projects: In collaboration with Dr. Donald Fischer, the students take the Implicit Association Test – a test developed by Greenwald and colleagues in the 1990s – at the beginning and end of each semester to reveal potential underlying bias.

How it works

Words or images flash on a computer screen, and participants quickly sort these according to instructions. Categories may include black or white faces paired with good or bad words. Accuracy and speed are averaged across trials for each person.

“Scores are based on reaction time, and the test evaluates automatic preferences individuals aren’t even consciously aware of,” said Young-Jones.

Young-Jones explained that in the context of contemporary society, prejudice is often expressed through subtle words and actions that are easily justified and difficult to detect. Many people understand it’s not socially acceptable to be overtly racist but may neglect to recognize their own prejudices; this dynamic can decrease the reliability of data gathered solely from explicit surveys.

“Because of social desirability, we want to see ourselves in a positive light. Students may say, ‘I’ve just taken this diversity class, so my prejudices are decreasing,’” said Young-Jones. However, to evaluate the full spectrum of individual bias, the combination of both implicit and explicit measures are necessary.

Since 2012, Young-Jones has collected implicit and explicit data in her classes. Three explicit self-report scales include the Modern Racism Scale, Explicit Racial Resentment Scale and Motivation to Control Prejudicial Reactions Scale. Results reveal that the motivation to control goes up from pre- to post-, which indicates that students wish to reduce prejudice. In addition, the Modern Racism Scale score decreases, which again is positive. Overall, the explicit and implicit results continually demonstrate the positive impacts of diversity curriculum.

Shining a light on insensitivities

But one woman who took Young-Jones’ class in spring 2016 recalls that these shifts in perspective weren’t always simple or seamless. One day, the class watched a preview of the documentary “Dark Girls,” in which a character made a derogatory comment about the appearance of African-American women. Unbeknownst to Young-Jones, another classmate laughed at the comment, which set off a flurry of reactions for one student. An African-American woman left the class in tears, with a strong sense of rejection and alienation.

Instead of being silent and feeling resentful, however, she expressed her concern to Young-Jones. This experience prompted deeper classroom dialogue about inclusiveness, group dynamics and word selection.