Archive for 2018

Ozarks history through a realistic lens

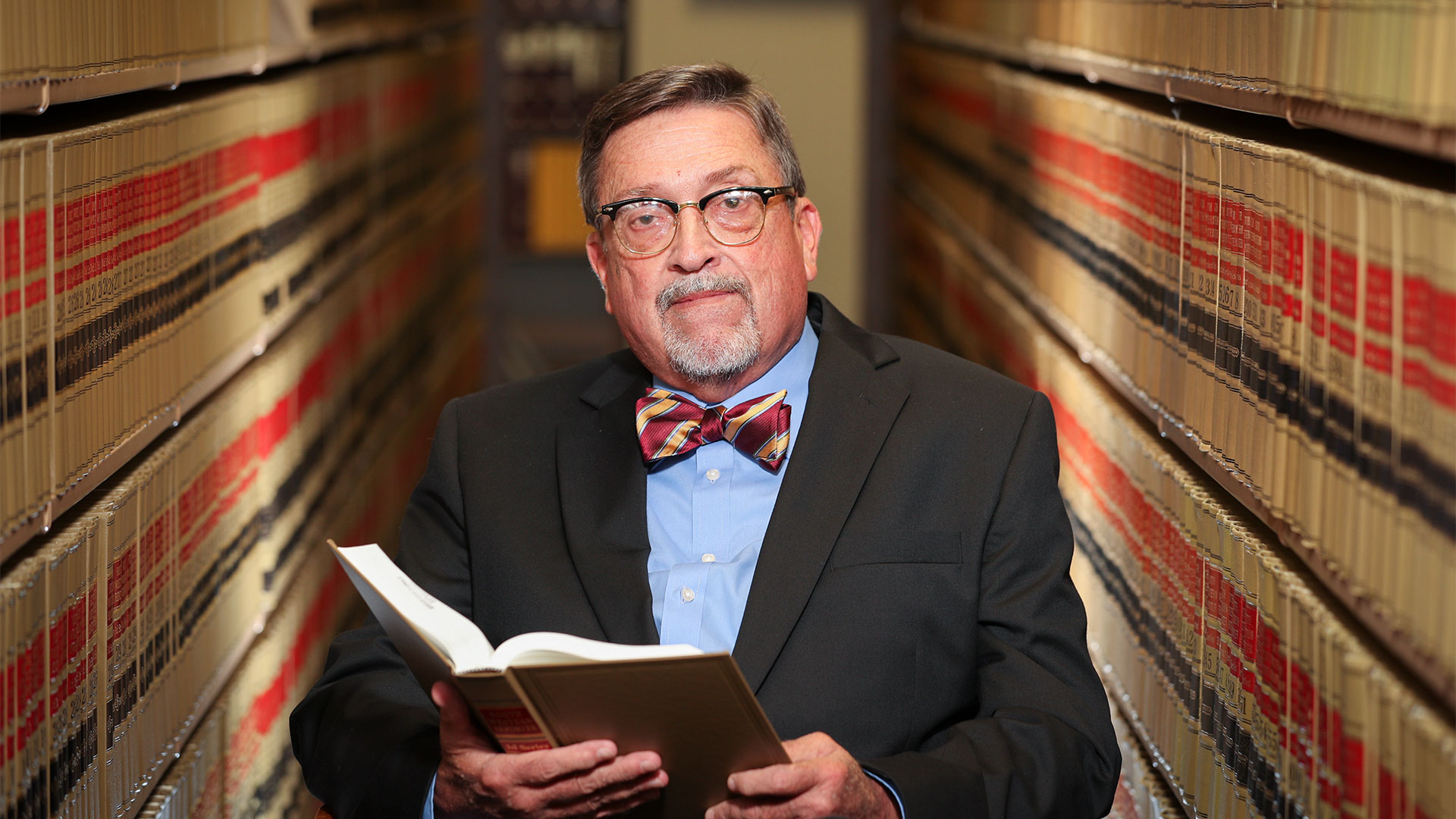

But Dr. Brooks Blevins, the Noel Boyd professor of Ozarks studies, works to change these misconceptions through his research. He pores over countless materials about the Ozarks and conducts oral histories to provide a truer picture of the area and the people who live here.

A lifelong Ozarker, Blevins grew up on his family farm in rural Arkansas. He always loved history. When he got interested in the Ozarks as a college student, he chose to study both and devote himself to research.

“Since I lived here, this topic was much more personal to me,” Blevins said. “I noticed there wasn’t much good history of this region. A lot of the writings were influenced by folklore and travel writers. They tended to be romantic and unrealistic.”

Map of the Ozarks. Map by Emilie Burke, maps and GIS student assistant, Missouri State University

What is the Ozarks?

The physical Ozarks is roughly 40,000-45,000 square miles. It covers much of the southern half of Missouri and a large part of northern Arkansas. It also extends into northeast Oklahoma and southeast Kansas.

While the physical Ozarks is well defined, its cultural boundaries are less so, Blevins notes. This is because people may live in the region, but do not identify as Ozarkers.

The first in a trilogy

Blevins has spent more than two decades discovering the Ozarks’ rich history. He has authored eight books, two of which are award winners.

His latest book – “A History of the Ozarks, Volume 1: The Old Ozarks” – came out in summer 2018. It’s the first volume in a trilogy that offers a comprehensive history of the region. No other book like this exists.

“I noticed there wasn’t much good history of this region. A lot of the writings were influenced by folklore and travel writers. They tended to be romantic and unrealistic.”

Volume one highlights the early days of the Ozarks before the Civil War. It chronicles the area’s formation and the lives of Native Americans. It also documents European colonialism and the mass migration of settlers.

Blevins writes about people as they hunted, fished, founded schools and churches, and developed communities. He tells colorful human stories within the context of what was going on in American history at the time.

Blevins says the most surprising discovery during his research was the central role “immigrant Indians” played in the old Ozarks. These displaced natives from east of the Mississippi River came from different tribes.

“For about two generations, thousands of them lived in the region. In the 1820s, they even attempted to establish a sort of autonomous Indian nation in the Ozarks,” Blevins said.

Gary Kremer, executive director of The State Historical Society of Missouri, has read Blevins’ book. He says the breadth and depth of his research is outstanding.

“This book will enhance people’s understanding of the Ozarks because he brilliantly narrates the many ways in which the land and the people of the Ozarks interacted to shape each other,” Kremer added.

The Jacob Wolf House in Norfolk, Arkansas, served as the first permanent courthouse in Izard County. Photo by Bob Linder

A sneak peek

Blevins is working on volumes two and three of his trilogy. The target publication dates are summer 2019 and 2021, respectively.

Volume two will focus on the long Civil War and Reconstruction era. Its main topics include slavery in the Ozarks, the secession crisis, the resulting war and the region’s reconstruction. It will also introduce the idea of the cultural Ozarks.

The third volume will pick up the story at the end of the 19th century into the 21st century. It will include a wide array of topics, from farming and industry to music and tourism.

“Underlying almost all the books’ subjects is an ongoing exploration of the perpetuation of cultural stereotypes and the role that the region’s image has played on its history and development,” Blevins said.

A large crowd gathered as Dr. Brooks Blevins shared about Ozarks history and explorer Henry Schoolcraft in September 2018. Photo by Bob Linder

Relating to the masses

While Blevins is an academic, he tries to write history books that connect with common folks. He wants people in the Ozarks to know they have a valuable regional history of their own and take pride in it.

“It’s often a warts-and-all story like the American experience in general,” Blevins said. “But there are many interesting and iconic people and things that had their origins right here in the Ozarks.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Main photo by Bob Linder

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Influencing the future of arbitration

Dr. Stanley Leasure’s work may give you one more thing to consider when you sign an employment contract or read the employee handbook. What happens when something goes wrong?

Probably no more than five percent of the lawyers teaching at law school have anywhere near 25 years experience.

“Many big companies want to limit your ability to sue them – of course they do,” Leasure said. “It’s messy and expensive. But more than that, it’s an exhibition that they don’t want.”

Leasure, a business law professor, was a partner in an Arkansas law firm for more than 25 years before joining the Missouri State University faculty. His interest in alternative dispute resolution – like arbitration, negotiation and mediation – began there.

Now he studies cases and rulings to deduce how the courts interpret the Federal Arbitration Act. He publishes articles on the precedents set forth and the discrepancies he sees. His work has influenced several court decisions. It has even been cited by attorneys appearing in the U.S. Supreme Court.

Arbitrators decide your future

Every day, more companies are placing clauses in their employment contract or employee handbook that state litigation is not an option in case a dispute arises. Instead, companies prefer – and are requiring the use of – arbitration.

Why arbitration? Because it is less costly, it’s conducted in private and it’s usually much quicker.

An arbitrator’s decision is considered final, legal and binding. Leasure is trying to influence how and when attorneys should be able to appeal the decisions.

“Who gets to decide? When are parties bound by an arbitration agreement? What issues are covered by the agreement? These are some of the questions I’m asking,” he said.

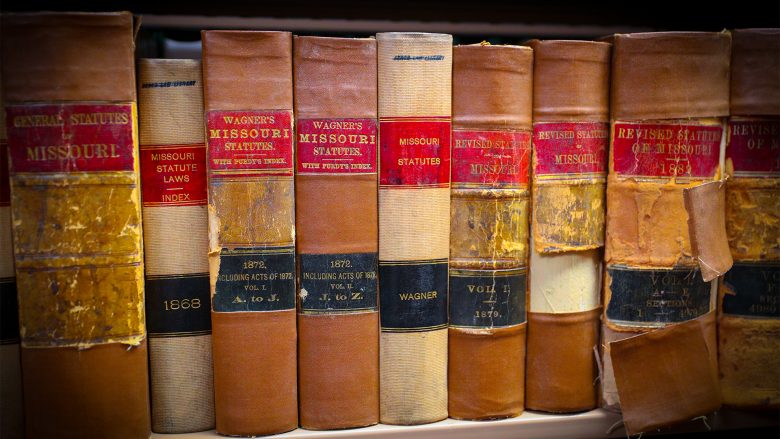

Volumes filled with Missouri’s state statutes line the shelves of the library in Missouri’s Court of Appeals. Photo by Kevin White

Pandora’s box

When the Federal Arbitration Act passed in 1925, it contained a few circumstances when an arbitrator’s decision could be overturned in court. Since then, more and more people dissatisfied with an arbitrator’s decision appeal to federal court.

Legal scholars have a unique ability to affect the development of the law.

“This is where Pandora’s box is really flung open,” Leasure said.

Courts interpret the nuances of those original exceptions differently. And several have expanded the exceptions beyond those in the Federal Arbitration Act.

While the courts have moved to revert to the original exceptions, some of the newer exceptions are still in play. Until all of the additions have been removed, Leasure expects more cases to make their way through the appeals process.

“It’s unsettled,” Leasure said, but it gives him great inspiration for future studies.

Ariel Kiefer, an MSU alum, and Dr. Stanley Leasure peruse Twitter for trending topics in alternative dispute resolution. Photo by Kevin White

Finding inspiration

Besides reading the latest literature, Leasure scours Twitter for hot topics.

Sometimes he approaches his high-achieving students about collaborating on a research project. It’s a virtual collaboration since he primarily teaches online courses. But students like Ariel Kiefer considered it a great experience.

“Dr. Leasure helped me explore a topic and let me have a substantial part in researching and framing the article,” said Kiefer, a 2015 MSU graduate. “The skills I learned with his guidance were a great help in law school.”

Leasure agrees. Collaborating with his students can accelerate research projects. Ultimately, that means he’s influencing the interpretation of the law in two ways at once.

“I’m getting my viewpoint in front of attorneys and judges in these articles, and they are citing our articles in their decisions,” he said. “I’m also coloring the way my students see these dispute resolutions. And they are taking that into their future careers – law or otherwise.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

Further reading

Warriors

She was referring to Maxine Hong Kingston’s 1977 book “The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts.” Moser, an expert on Kingston’s work, recently edited a collection of essays that commemorated the 40th anniversary of its publication.

With co-editor Dr. Kathryn West, Moser curated a diverse set of interpretations of this famous book.

“The essays focus on different issues,” said Moser — in part because the book is relevant to so many fields of study. “It’s literary; it’s memoir,” she said. “And it’s meaningful for gender studies and ethnic studies.” Its publication also marked a milestone in Asian-American writing.

However, Moser said, it’s a mistake to assume “The Woman Warrior” is a definitive version of Asian-American experience. “It’s not a guidebook to Chinese American culture,” she said.

In her own essay, Moser noted that since “The Woman Warrior” was published, its author has resisted attempts to present her work as the exemplar of the Asian-American experience.

“’The Woman Warrior’ suggests that stories, fantasy and subjective experience are as much a part of reality as objective fact.” — Dr. Linda Trinh Moser

“Kingston continues … the process of questioning and revision,” Moser wrote. “In this way, she resists the assumption that an ethnic American writer should serve as a guide whose sole purpose is to provide … information for her readers.”

In some sense, then, Kingston’s book asserts a deeper purpose: a commitment to understanding the complexity of identity and desire to encourage a similar process in her readers.

And this quality makes Kingston’s narrative intensely individual. “This is one person’s experience,” Moser said.

This may be the reason “The Woman Warrior” was labeled a memoir of Kingston’s life growing up in California with parents who had immigrated from China. Since its publication, though, critics have questioned whether the story ventures too far beyond the material reality of Kingston’s own experiences to really be “authentic” or “real.” It draws on fantasy and myth, such as the story of Fa Mu Lan (the basis of Disney’s “Mulan”). The narrative also stretches time and space in ways that can’t be strictly factual.

This, according to Moser, is the point. “’The Woman Warrior,’” she wrote, “suggests that stories, fantasy and subjective experience are as much a part of reality as objective fact.”

Society and silence

The search for layers of meaning is central to Moser’s work as a literature scholar.

“I seek out books that cross cultures and tell stories about protagonists who are trying to maneuver different cultures,” she said. “I do that in my teaching, and I do that in my research as well.”

This approach means she often exposes her students to new perspectives. By studying literature, they find new areas of understanding — and sometimes commonality.

“I seek out books that cross cultures and tell stories about protagonists who are trying to maneuver different cultures.” — Dr. Linda Trinh Moser

For instance, she said “The Woman Warrior” brings up ideas that are relevant to people from a variety of cultural backgrounds. We all have to navigate the different cultures in which we live, the ways we define ourselves and the ways we are defined by our communities.

Kingston’s sense of self is complicated by a growing awareness of her “minority” status as she is growing up. Among Chinese immigrants, she is bombarded with messages about female inferiority; in the larger U.S. community, she faces racism as well as patriarchy.

“Kingston is forthright about social injustice, not only in Chinese-American culture, but in Anglo-American culture as well,” Moser said. “As a woman, she feels she’s been silenced; that’s where the ‘warrior’ in the title comes in.”

Moser continued, “But she’s saying, ‘I don’t want to just point the finger at the patriarchy in my parents’ culture. I want readers to recognize the patriarchy that occurs in their own culture.’”

And as Moser’s previous research reveals, this kind of cultural examination isn’t unique to Kingston’s writing.

As a literature scholar, Dr. Linda Trinh Moser explores how concepts of identity, race, culture and ethnicity are handled in text. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Belonging and betrayal

In multiple publications, Moser has explored the career of Winnifred Eaton, described as “the first novelist of Asian ancestry to be published in the United States.”

Eaton’s success as a bestselling novelist during the early 20th century attracted Moser’s attention. As she dove into Eaton’s work, she found an intriguing level of complexity.

Eaton, who most often wrote under the pen name Onoto Watanna, was biracial. Her father was British, and she implied (through her choice of pen name and other strategically leaked details of her life) that her mother’s ancestry was Japanese. In actuality, her mother was from China.

According to Moser, Eaton’s decision to engage in this ethnic masquerade was influenced by the stereotypes of her time.

Moser wrote, “During the early part of Eaton’s career, North Americans drew a sharp distinction between Chinese and Japanese immigrants. Although anti-Chinese sentiment ran rampant at the turn of the century, the Japanese were admired … Eaton, aware of the difference, exploits notions of class perception” by claiming Japanese, rather than Chinese, heritage.

Some critics judge Eaton’s subterfuge harshly. Moser wrote, “Eaton’s manipulation of Japanese stereotypes makes her seem more interested in perpetuating false and exotic versions of Asian identity than in presenting actual experiences. Indeed, critics often interpret Eaton’s concealment of her Chinese ancestry as a lack of integrity.”

And, historically, this perspective cuts deep. According to Moser, “(In early scholarship), when mentioned at all, (Eaton’s pen name Onoto Watanna) stood for racial, ethnic or cultural betrayal.”

But Moser’s research brought her to a more nuanced understanding.

Timeless questions

Working within the popular romance genre and navigating the social prejudices of her time, Eaton found ways to highlight strong female characters and cross-racial storylines.

“(Her) characters are always capable, clever, inventive and resourceful,” Moser noted.

Her stories resist “the image of Asian women as victims … Refusing to rely on male protection, these heroines are self-reliant,” Moser wrote. They “support themselves financially,” a challenge Eaton knew much about; as a working writer in Jazz Age America, she did it, too. In addition to writing short stories, travel essays and novels, Eaton wrote screenplays in Hollywood.

Moser recognizes how Eaton’s “Japanese” persona “allowed her to avoid the animosity Chinese immigrants experienced and to present a biracial Asian identity similar to her actual one, despite its inauthenticity.”

Even so, Eaton’s choice is a denial of her ethnic identity, which makes it hard for modern audiences to accept. To Eaton, the stereotyping of Japan as “better” than China must have seemed arbitrary. To fight against the prejudices of her time, she used the cultural ignorance as a weapon. If most Americans couldn’t tell the difference between Japanese and Chinese immigrants, why shouldn’t she pretend to be Japanese?

And in this way, Eaton was wrestling with the same questions Kingston posed decades later in “The Woman Warrior”: How do I define myself? How do others perceive me? How much do these versions of me overlap? How do I fit in to the world I live in?

In a country as multicultural and ever-changing as the United States, such questions are always fresh and relevant. Moser’s research illustrates how literature — whether scholarly favorites like “The Woman Warrior” or popular novels like the ones Eaton wrote — can be a platform to explore such questions.

When students, scholars or book clubs read and discuss books, they’re often contending with race, class and gender. Such discussions help illuminate the ways these issues affect and define our own identities.

Dr. Linda Trinh Moser exposes her students to new perspectives by studying literature that crosses cultures. Photo by Jesse Scheve

The ‘cold case files’

Just as Moser’s research explores the richness and complexity of American literature, she applies a highly dimensional outlook toward the students she teaches and advises.

“She’s always been very empathetic about the ways life can get in the way of our goals,” said Moser’s colleague Dr. Keri Franklin.

In describing Moser’s dedication to students, Franklin recalled a specific event.

“She’s always been very empathetic about the ways life can get in the way of our goals.” — Dr. Keri Franklin

“She had these file folders,” Franklin said. “She called them her ‘cold case files.’ They were people who hadn’t graduated. She went through them all and found out what they still needed to earn their degrees. She contacted each of them, and many people ended up graduating because she did that.”

Moser’s effort was important for student success and retention, but, Franklin said, that wasn’t the point.

“She didn’t do it for the numbers. She did it because she wanted to see people finish what they’d started. I really love that about her.”

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Breeding grapes the smarter way

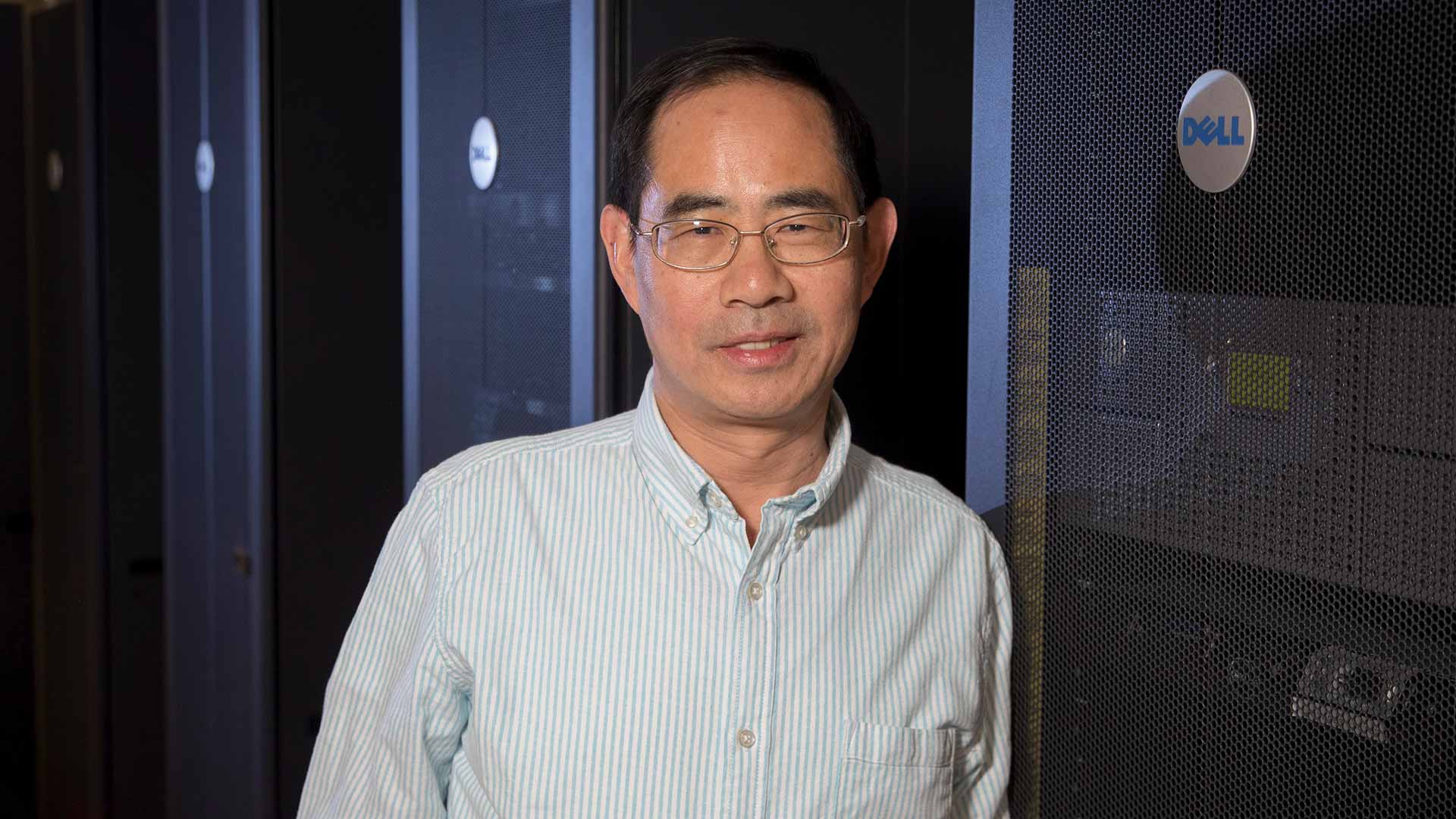

That is why agriculture professor Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang and his team of researchers at Missouri State University are exploring grape genetics. They use cutting-edge DNA marker technology to expedite traditional breeding of grapes, which may take more than 20 years to release a new type of grape, also known as a cultivar.

If you don’t have sustainability of your vineyard, you can’t make a profit. Growers are now recognizing the importance of growing hybrids here. — Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang

Their ultimate goal is to develop and release new hybrid grape cultivars in the region, which have desirable traits from both European grapes and Missouri’s official state grape, the Norton. Compared to European grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Norton is more disease-resistant and cold-hardy.

“Growers in Missouri want to have European grapes in this area, but the grapevines can’t last long due to the cold weather and fungal diseases. Even if pesticides are intensively applied, European grapes often die within five years because of complications of the cold weather,” said Hwang, who has received nearly $2 million in research grants. “If you don’t have sustainability of your vineyard, you can’t make a profit. Growers are now recognizing the importance of growing hybrids here.”

Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang clips grapes from the vines on the Mountain Grove campus. Photo by Bob Linder

Crossing grapes

For the past six years, Hwang and his team have been working on creating mapping populations – a minimum of 200 seedlings from a controlled cross of two types of vines – to look for genotype (DNA information) that associates with desirable phenotypes (physical characteristics).

Team member Surya Sapkota, an MSU/University of Missouri collaborative doctoral student, said they produced the first genetic map from a Norton-Cabernet Sauvignon cross. They also created mapping populations for the Chambourcin-Cabernet Sauvignon cross and the Jaeger 70-Vignoles cross.

Jacob Schneider, Li-Ling Chen, Rayanna Bailey and Surya Sapkota work in the lab at the Fruit Experiment Station. Photo by Bob Linder

Decoding DNA

In the lab, MSU research specialist Li-Ling Chen trains graduate students to isolate DNA from each seedling by grinding up a small piece of leaf tissue to look for DNA markers. These markers are genes or DNA sequences with a known location on a chromosome allowing them to predict each seedling’s phenotype, such as berry quality or disease resistance.

This marker-assisted selection process not only reduces the long “wait and see” period in traditional plant breeding, but also results in a more accurate selection of what the progeny – or offspring – will be.

“The biggest feat of Dr. Hwang’s lab so far may be the mapping populations established because no improvement or selection of traits can begin until they are available,” said Jacob Schneider, an MSU plant science graduate student. “The molecular breeding process resulting in the mapping population saves considerable work, water, labor cost and time involved in field trials – big factors for sustainability.”

Grapes are gathered, labeled and taken to the lab for further research. Photo by Bob Linder

Studying different traits

From a plant’s ability to root during dormancy to its disease resistance and more, Hwang leads his team in analyzing various traits in their breeding populations.

For example, Schneider’s research looks at dormant hardwood cuttings to see how well they root.

“Norton dormant cuttings don’t root well, but the Cabernet Sauvignon ones do, so I look for DNA markers that allow dormant rooting by screening offspring of these parent cultivars,” Schneider explained. “The ones that do root should have DNA for that rooting ability. When we combine the rooting and markers data, we can select for that trait in a population.”

Using DNA marker technology. Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang is changing the grape breeding industry. Photo by Bob Linder

Making a discovery

Hwang’s efforts to study another trait known as downy mildew, a severe fungal disease, from the same Norton-Cabernet cross recently paid off.

His lab discovered the downy mildew resistance markers on chromosome 18 by constructing a high resolution genetic linkage map combining two types of DNA markers – simple sequence repeat (SSR) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).

This map is the first-of-its-kind. It was made possible by a collaboration with Cornell University, which assisted Hwang with the SNP marker information his lab did not have.

“This finding is very important for growers because downy mildew is a big disease,” Hwang said. “We can now predict whether a progeny with Norton background will be resistant or susceptible to this disease, so growers will know the resistant one to grow and won’t have to spray as much chemicals.”

Dr. Chin-Feng Hwang’s lab partners with Cornell University to speed up the traditional breeding of hybrid grapes. Photo by Bob Linder

Releasing a new cultivar

Each year brings Hwang closer to releasing a new Norton-based hybrid grape cultivar. He estimates it will happen in the near future.

“We do have a potential candidate from Norton cross with Vignoles,” said Hwang. “It looks pretty good, but needs to go through multiyear, multiple location evaluation first.”

For Missouri grape growers eager for a new hybrid, that day cannot come soon enough.

“They’re already asking, ‘how soon?’” said Hwang. “We’re working on it.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Main photo by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Hope in the fight against HIV

In the 1980s and 1990s, an HIV diagnosis was a death sentence.

With the development of a cocktail of prescriptions, survival rates skyrocketed.

Still, about 50,000 people in the United States are infected with the virus each year. And one out of every eight people who is HIV positive doesn’t know it.

Dr. Amy Hulme, assistant professor of biomedical sciences, studies the inner workings of the virus and how it replicates. She hopes her work will lead to the development of a vaccine or better drugs to prevent transmission.

In the last 10 years, she published 11 articles on this research in publications like the Journal of Virology. She also served as a peer reviewer for this journal.

Hulme is fascinated by HIV because it does a few things that really should not work. It is unique among viruses because it mutates, making it difficult to predict the usefulness of medication.

It is also unique because it is one of only two human viruses classified as a retrovirus. HIV gained this classification based on how it copies itself inside a cell. First it transfers the RNA genetic material of the virus into DNA – a process called reverse transcription. That DNA then gets inserted into the cellular DNA.

Reverse transcription, explains Hulme, hardwires the virus into the cell. But in order for the reverse transcription to occur, the coating of the virus has to be shed.

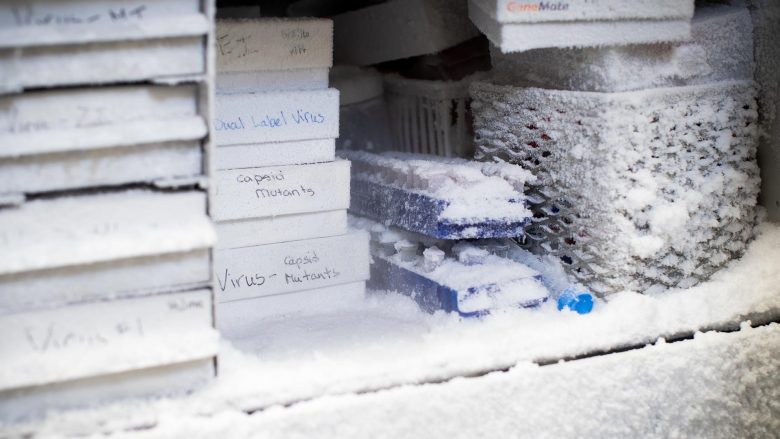

In Dr. Amy Hulme’s lab, she studies how HIV replicates itself in cells. Specifically, she looks at the how and when the capsid (or coating) comes off. Photo by Kevin White

Shift in thinking

Or at least that’s what the scientific community originally thought – that it was a linear progression from the uncoating to reverse transcription. No one truly knew how and when this uncoating occurred – or the significance.

Her post-doc adviser, Dr. Thomas Hope from Northwestern University, believed that the virus entered a cell and the coating fell off immediately. Many others in the field thought uncoating happened before reverse transcription.

During her post-doc work, Hulme discovered something different. She observed the virus copying DNA in cells while it was still coated.

“It was my ‘a ha’ moment,” Hulme said. “It made me think, ‘maybe the steps kind of happen at the same time.’”

If the coating stayed on, would the DNA ever become one with the host cell? Hulme knew that the biological community would benefit greatly from further studies on this step. After all, blocking the uncoating step might mean a medicine or vaccine could be developed to prevent HIV.

Hulme established an experimental technique using an instrument called a flow cytometry. This device analyzes particles in a fluid as they pass through a laser. Since she developed this new technique, it has been included in numerous studies – by her and others in the field – to dissect the how and when of the uncoating process.

Dr. Amy Hulme created two experimental techniques to help study HIV. Photo by Kevin White

Medical mysteries

Owl monkeys have a protein that blocks HIV replication, so they have been key to this research.

Hulme delivered a drug to cultured owl monkey kidney cells, which affected how that immunity protein stuck to the coating. Then she removed the drug at different intervals and used a flow cytometry to determine how much of the virus was coated and uncoated at each stage.

If the virus was uncoated, she noted, it could no longer be protected by this restriction protein.

The other method Hulme’s lab uses for HIV research incorporates fluorescent microscopy.

In this method, she and her students label the virus with fluorescent proteins. Then, the proteins will glow under the microscope and can be monitored to detect the coating at different times.

“If you get the same answer with both techniques,” she said, “you can be much more confident that result is a real result, and not due to some weird experimental artifact.”

Uncoating seems to impact a lot of other steps that happen kind of at the same time, and immediately after it. It’s an important step to understand, it’s just very difficult to study. — Dr. Amy Hulme

Her studies determined that the majority of uncoating happened within the first hour.

“When we delay reverse transcription using a drug, we also delay the process of uncoating,” said Hulme, which leads her to the conclusion that there is some interplay between the steps. “It’s becoming very clear that it is a very central step that affects a lot of different steps in HIV replication.”

Hope is proud of the impact Hulme has had on the field.

“She had great success tackling a major research mystery in the HIV life cycle,” said Hope. “Because her approach was unique, it was controversial in the field at first. But ultimately, she was correct.”

Now that there is more understanding on the process, Hulme is beginning to look at how untreated AIDS makes its way to the brain and causes neuro-cognitive disorders.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Past, present and power

Dr. Billie Follensbee, an art historian and archaeologist who specializes in ancient Mesoamerica, has spent years illuminating a fundamental aspect of humanity in artifacts from the Olmec civilization, which once thrived along the Gulf Coast of present-day Mexico.

Olmec civilization is famous for dramatic, blocky sculptures that often appear androgynous.

Follensbee says, “The faces are often very naturalistic, but the bodies tend to be very stylized. Because of that, it’s difficult to tell whether a figure is male or female.”

She set out to catalog Olmec sculptures by sex and gender, but she struggled to find consistent guideposts in the existing scholarship.

“The only pattern was that if it was large and important-looking, it had been classified as male. And if it was small and unimportant-looking, it was assumed to be female. Basically, indications of power were automatically considered male.”

Dr. Billie Follensbee studies and teaches about art and artifacts from non-Western cultures including Africa, Oceania and the Americas. These African masks are from the Mace collections donation to Missouri State. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Patterns

This paradigm, Follensbee believes, reveals more about those who first chronicled the Olmec than about the Olmec themselves.

“There was a great deal of gender fluidity in Native American cultures, which was originally left out of history books because the people who recorded it were from Western cultures, where gender roles are traditionally rigid,” she says. “They were uncomfortable with this fluidity, or they just didn’t understand it.”

To avoid making similar assumptions, Follensbee needed a Rosetta stone, a way of decoding the sculptures that wouldn’t perpetuate biases of pre-existing research.

She turned to Olmec ceramic figurines, which she says, “are much more clearly sexed than the sculptures.” By carefully cataloging body forms, jewelry and clothing associations, she created a lexicon of male and female characteristics. Since these associations remained roughly consistent over several centuries, they could reasonably be assumed to appear in Olmec sculptures, too.

And, Follensbee found, they did. Many were subtle, but straightforward. For example, identifiers included: pinched waists and wide hips for women; straight-sided waists for men; high-waisted, wide belts and skirts for males; low-slung skirts and thin, beaded hip-hugger belts for females.

Follensbee’s lexicon provides a clear methodology for identifying gender in Olmec sculptures, one that isn’t influenced by an artifact’s size or apparent importance. She published these findings in a series of articles, the latest as a chapter in the volume “Dressing the Part: Power, Dress, Gender, and Representation in the Pre-Columbian Americas,” which she co-edited with Dr. Sarahh E. M. Scher.

Of course, it sometimes gets complicated. A figure with anatomically female features might wear clothing associated with males, or a figure might have male features and female paraphernalia.

“The conclusion I came to,” she says, “was that they were appropriating the power of the other gender. A man might be appropriating the idea of motherhood, or a woman might be assuming hereditary power from her father. Or she could be fulfilling a role that may have traditionally been male — such as a ruler — but was in this instance taken on by a woman.”

And sometimes gendered characteristics were intended to convey a completely different meaning. “For example,” she says, “one male figure wore a weaving tool that is typically associated with females. But this was a man outside of the Olmec area, and he was likely adopting this to show that he was associating himself with the Olmec, rather than as a feminine symbol.”

Altogether, it points to a complex understanding of men and women within Olmec society, one that resonates today.

Dr. Billie Follensbee’s latest research explores art and artifacts from ancient Native North American cultures. Follensbee and her two student grant assistants, Sarah Teel and Leslie Dunaway, created these birdstone reproductions. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Perspective

Follensbee’s research provokes discussion in the archaeological community.

She says, “Some people become upset because they say that this is ‘revisionist history.’ But it’s just correcting misrepresented history. In the past, if a scholar found the grave of a man wearing a gold headdress and expensive garments, the tendency has been to say, ‘This must be a king.’ But for the grave of a woman who had the same precious ornaments, the conclusion was, ‘In this culture, it must have been prestigious to decorate the grave of your wife.’”

These assumptions have had the effect of obscuring women within the historical record. Follensbee says, “If a figure wasn’t absolutely, obviously female, it was assumed to be male.”

And, she contends, determining the true gender of an important sculpture is far more than an academic puzzle. It has real implications for how we think about our world now.

“People sometimes characterize the concept of women in leadership as a new idea — as if women have never held positions of power before. When we look at the archaeological record from all over the world, however, we find powerful women throughout history,” she says.

“This research not only tells us about these objects. It tells us about ourselves.”

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Ensuring your loved ones’ safety doesn’t hang in the balance

You could be pretty dangerous, according to Dr. Susan Robinson.

“That’s the person who really has a great risk for falling and injury,” she said.

The perfect thing is the person who has appropriate confidence in their balance and actual abilities.

Robinson, a professor of physical therapy, focuses her research on a variety of areas within the field.

She looks for ways to prevent falls in older adults. Robinson’s also partnering on several projects that examine balance and gait of individuals with vestibular dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease and a variety of other mobility impairments.

Robinson has published 20 articles and abstracts on balance- or rehabilitation-related topics and presented at more than 15 conferences.

Her research includes helping injured musicians who play string instruments get back to performing. She’s also helped people find technology that improves their gait. But helping people improve their balance – and ultimately their safety – is where her work really shines.

Dr. Susan Robinson fits a patient in a harness for the Bertec Balance Advantage, which uses virtual reality to measure balance. Photo by Kevin White

Stopping expensive accidents before they happen

The vestibular system is part of the inner-ear system. It works with your vision and proprioception, or awareness of body position, to maintain your balance.

If a person loses some of the information provided by these three systems, it can lead to falls. That can lead to expensive stays in hospitals due to hip fractures or other injuries.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), falls cost Medicare more than $31 billion in 2015. The average hospital cost for fall-related injuries is more than $30,000 and the estimated lifetime cost of a hip fracture is more than $80,000.

It’s so valuable if you can see that someone’s at risk for falling and do something to intervene. You can prevent a fall and a hip fracture, which costs the health system an incredible amount.

Robinson and Dr. Jason Shaw, an assistant professor of physical therapy, took their show on the road to help people improve their balance.

For the past eight years, Robinson, other MSU physical therapy faculty members, and MSU physical therapy students have participated in a nationwide annual Fall Prevention Awareness Day at local senior citizen centers and independent living facilities in the Springfield area. One stop led to an interesting discovery.

“I looked over, and Dr. Shaw had the physical therapy student holding onto the gait belt while guarding the person being tested,” Robinson said, noting that caregivers place a gait belt on patients with balance or mobility issues as they transfer from one location or position to another. “I told him, ‘Don’t let them hold the gait belt. That’ll change the score.’ And he says, ‘I don’t think it’ll change the score.’”

They performed the gait assessment with hands-on and off the gait belt.

In this study, participants’ perceptions of their balance and actual balance scores agreed. There was not a significant difference between Shaw guarding the person while holding and not holding onto the gait belt.

“Her work could have a profound effect on patient safety when testing balance,” Shaw said.

Using technology, like the Bioness system, Dr. Susan Robinson has seen great improvements in those with impaired gait. Photo by Kevin White

What lies ahead

The meaning of the project is significant. As a result, it warrants further study, Robinson said. She and Shaw will take the experiment further.

They want to know if there’s a difference in balance scoring between guarding by a physical therapist with Shaw’s expertise, and a physical therapy student doing the same.

“When you’re a physical therapist in a clinic and don’t know a patient’s abilities, you’re going to be safer if you have a hand on the gait belt while guarding a patient,” Robinson said. “But you don’t want to change their score, so I think that’s really an interesting project.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Read the leaves: How plants respond to the world

Wait, professor of biology, studies how plants respond to environmental variation. It’s been his focus for 20 years.

“We learn about how fire, temperature and light affect physiological processes – like photosynthesis,” said Wait. “And ultimately we can show how multiple factors affect not just this tree, but an entire forest or the whole ecosystem.”

Photo by Kevin White

Nanoparticles

His research team investigates many variables that affect plant growth. He said, at its core, the research is important because plants are the base of all terrestrial food chains.

Usually when I’m coming into a project, it’s because somebody wants to know the why.

For example, 25 percent of all consumer products now contain materials referred to as engineered nanomaterials, ENMs. So in 2013, Wait joined other faculty from Missouri State University’s College of Natural and Applied Sciences to develop the Carbon Nanotube Life Cycle Working Group.

One of his collaborators is Dr. Laszlo Kovacs, geneticist and biology professor. They are investigating how nanoparticles – which will enter systems through the landfills or when washed down the drain – may be toxic to plants and insects.

“While these materials may have been proven safe as integrated components of electronics, cosmetics or clothing, their physicochemical characteristics change when they are released to the environment,” said Kovacs. “Their safety to plants, animals and microbes may not be guaranteed any longer.”

Wait notes that insurance companies are driving this need to know.

Photo by Chris Nagle

Mustard and moths

To understand the impact, Wait and Kovacs used Arabidopsis, a plant in the mustard family that is commonly used in plant genetic and physiological research. They grew the plants in media containing engineered carbon nanotubes.

Then Wait measured the plants’ physiological responses using a gas exchange system. He tested to discover if the ENMs caused an imbalance in the plants’ carbon and nitrogen ratio, whether the stomates closed up (making photosynthesis impossible) or otherwise affected a plant’s physiology.

In the gas exchange chamber, which mimics the exact environmental conditions of the growth chamber, the plants showed only minimal signs of reduced photosynthesis and growth from engineered carbon nanoparticles.

“I measure the plants’ photosynthetic rates. Then I change the light carbon dioxide concentration and elucidate the mechanisms affecting photosynthesis,” said Wait.

Then Wait studied how diamondback moths are affected by directly feeding on the ENMs or how they were affected when exposed to the Arabidopsis grown in the nanoparticles.

The carbon nanotubes didn’t deter the insects from the food – Arabidopsis is the feast of choice for this type of moth – and didn’t kill them either. Wait noted that the moths continued to go through metamorphosis and grow into adults.

But the moths’ reproductive abilities were reduced by 50 percent. Also, the moths ate more but weren’t growing as well due to diminished food quality.

The entire genome of both the Arabidopsis and diamondback moth have been sequenced, which means Wait and Kovacs were able to identify how genes were affected by the exposure.

“We expect to identify a set of genes that change their expression when the plants are exposed to engineered nanomaterials,” Kovacs added, “and at what concentrations these ENMs are harmful to plants.”

Photo by Kevin White

Setting the standard

Previous studies of how these nanoparticles decompose and affect plants have yielded inconsistent results.

“There was a study that showed that if you put carbon nanotubes in the soil, you could increase the size of a melon like 20 or 30 percent. Others have shown that it’s toxic at the seedling stage, but the concentrations vary a lot,” said Wait.

Wait hopes their experiments establish a standard protocol for evaluating toxicity. He and Kovacs are writing standard operating procedures for screening nanoparticles for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Wait has had three graduate students complete theses on this research, and they are in the process of submitting their research results to scientific journals.

Photo by Kevin White

The silver tests

Now, Wait and Kovacs are conducting similar experiments using silver nanotubes, which are often found in antibiotics.

Even in the early stages of the experiment, it was obvious the silver nanotubes were having a much more detrimental impact and turning on and off genes in the plant and moth.

“The silver nanotubes are found in antibiotics and silver kills bacteria, which is good,” said Wait. “We’re trying to find out at what concentration consumption is affected? Growth? Does it affect pupation? Does it affect survivorship?”

With an estimated 100,000 tons of waste in the landfill containing nanomaterials, this research of engineered nanoparticles in the environment is growing in importance.

“It is not only important to know that products are safe during their service life to consumers,” said Kovacs, “but that they are safe after they are disposed or released to the environment.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Delving into the science of tracking

Known as returnable transport items (RTIs), these unsung heroes of the supply chain allow businesses to move goods efficiently and sustainably. While these plain looking containers may seem worthless, they are valuable reusable assets that hurt a company’s profits if they are lost, stolen or damaged.

“Imagine a large brewery that distributes millions of kegs a year. If they cost $100 each, it’s a huge investment,” said Dr. Barry Cobb, associate professor of marketing at Missouri State University.

Photo by Kevin White

Understanding the problem

The main issue with RTIs, Cobb notes, is keeping track of them – especially when an RTI fleet grows bigger. So the best solution is limiting the fleet size by moving items through the supply chain loop as quickly as possible. This cuts down the cycle time, which is the time it takes for an item to leave the factory after it is filled to when it comes back for refill.

Using breweries as an example, Cobb explains that they cannot control how fast people or restaurants use up beer from a keg. However, they can often control the speed it moves from point A to B.

“The faster kegs move through the supply chain, the fewer of them are needed, which means less investment and a more sustainable model,” said Cobb, who has published more than 30 book chapters and articles about operations management, supply chain management and logistics models.

Photo by Kevin White

Making smart predictions

Although companies use technology such as Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) to track RTIs at different points in the supply chain loop, these assets can still go missing or be delayed for several reasons. The RTIs are mainly scanned only at fill locations, the fleet is only partially tagged and RFID does not have GPS tracking.

“Forecasting when containers will return is the biggest challenge,” Cobb said. “If we can develop an accurate forecast of returns without GPS technology using fill-to-fill cycle times, this provides a lot of value to a company.”

Cobb is trying to do just that. In recent years, he has focused his research on helping companies better track their RTIs and save money. An encounter with Visibility, an asset management company that works with large breweries, gave him the data he needed.

Using statistical software, Cobb analyzes the data to develop methods that are more precise to track RTIs. The methods estimate probability distributions for cycle time and return rate of containers in a fleet.

Photo by Kevin White

Average is not enough

One area he worked on involved looking at the overall cycle time distribution instead of average cycle time to predict returns.

The latter, which many companies rely on, does not give a full picture of what is going on. It fails to consider RTIs that return to the factory before or after the average time.

For example, if an average cycle time for containers is 60 days, but more than 60 percent of them return before 60 days, a company will greatly underestimate returns if it builds a forecast based on the average number. Also, because some containers have very long cycle times, the returns to the factory can include containers filled more than a year in the past.

“While it’s nice to know the average, what helps more is to know what the entire distribution looks like because this helps predict how many containers return one week or two weeks, etc. from being filled,” Cobb said.

Photo by Kevin White

Real-world impact

Tom Hare, operations manager of Visibility Asset Management Solutions, believes the most vital part of Cobb’s research is the credibility and science behind his methods as current methods can rely a bit too much on gut feel.

“His ability to use techniques that give a degree of confidence and accuracy is invaluable to our company and customers.” — Tom Hare

“We give lots of data to clients but they don’t really know how to use or interpret it,” Hare said. “Barry is able to model the data in such a way that questions like ‘how many assets do I need?’ are being answered. His ability to use techniques that give a degree of confidence and accuracy is invaluable to our company and customers.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Main photo by Kevin White

Further reading

Keeping up with machines: Artificial intelligence in math

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Two players place their black or white stones on a 19 by 19 board to participate in an ancient board game, Go.

It’s a strategy game, similar to chess. But for Dr. Xingping Sun, it’s more than a game: It’s been an inspiration for his research.

“The simple rules of Go give rise to the most complicated board game, much like the evolution of modern mathematics from a few simple axioms,” Sun said with an admiring smile.

“Sun is one of the few mathematicians in approximation theory who is working in the direction of artificial intelligence.” — Dr. Jeremy Levesley

A mathematics professor at Missouri State University, Sun researches stochastic modeling, which uses important – but random – variables to predict outcomes.

Go is estimated to have more possibilities for moves than atoms in the whole universe. Working through all of the possible moves, which traditional artificial intelligence does, is a “hopeless way to play the game, even for the fastest computers in the world,” said Sun.

That was what Sun thought until March 2016, when AlphaGo, created by Google, beat all the best human Go players for the first time.

Intrigued by the algorithm that let AlphaGo drastically narrow down the possibilities, Sun now employs similar methods to model real-world problems of high complexity – like weather phenomena and early diagnoses of incurable diseases.

“Sun is one of the few mathematicians in approximation theory who is working in the direction of artificial intelligence,” said Dr. Jeremy Levesley, professor at the University of Leicester.

Sun boasts more than 50 publications in math and technology journals. He continues to be fascinated by the overlap between those two fields.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

The center of his research

For one recent study, Sun looked at polygons. He knew that when you connect the midpoints of the edges of polygons, a new, smaller polygon emerges. If you continue this process, you eventually land upon the center of gravity of the original polygon.

Building on that idea, he wondered what would happen if he used the stochastic model to select random points in a polygon instead of the midpoints.

In summer 2017, he had a team of undergraduate research students, funded by the National Science Foundation, look at this. They simulated many random polygons, selected random points along the edges, connected the points and repeated the process until the points met. After doing this more than 100 times, the research team found that the polygons merged to a single, random spot. Not only that, but the polygons hit that spot at the same rate as the polygons that used only the midpoints.

Next, Sun will have his students figure out the exact chances of random polygon sequences converging to specific, predetermined points.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Building on the polygon

“For mathematicians, it is often a long time before their work gets used in the best way, but I am confident that many of the results of Xingping’s research will perhaps help cure diseases, help in mineral discovery, or build more efficient infrastructure.” — Dr. Jeremy Levesley

Sun’s research and the concept of AlphaGo are similar. Both are finding easier and better ways to find random points and convert them into something meaningful.

In Sun’s case, he used video games as an example. If there are three choices on the screen, the computer doesn’t know what the player will pick. The game computes random choices the player makes and creates a game around it.

With Sun’s research, the computer wouldn’t be working to keep up with the player’s choices. Instead, the video game could predict what the player would do next. Rather than keep up, it would be leading the way.

“For mathematicians, it is often a long time before their work gets used in the best way, but I am confident that many of the results of Xingping’s research will perhaps help cure diseases, help in mineral discovery, or build more efficient infrastructure,” Levesley said.

When asked for his motivation, Sun laughed, and said, “I was scared by the computer intelligence. Secondly, it’s really a curiosity.”

- Story by Tori York

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Between the lines

“Imagine you’re making a pie,” Dr. Telory Arendell says. “You make the crust, put the filling inside and put the crust on top. Then you go around the top and shave off the part that’s extra, the part you don’t need.”

But why do you think you don’t need it? Maybe only because you’ve been told it’s not part of the pie.

“For me, that ‘extra’ is what’s actually most important, even though many people would throw it away,” Arendell says. And she isn’t really talking about pie.

Arendell, associate professor in the department of theatre and dance, uses this metaphor to describe her favorite theatrical experiences – moments that surprise the audience because they don’t quite fit our expectations of a night at the theater.

“When I write about movement on stage, I try to recreate the action with words that dance.” — Dr. Telory Arendell

“Performance art, experimental theater, what was called ‘happenings’ back in the ’60s,” Arendell says. “I love that stuff.”

Audiences sometimes worry that without the familiar rhythms of the theater, without clear heroes and villains and the promise of a resolution by final curtain, it will be hard to understand what’s happening on stage.

But, Arendell says, “You understand it in a different way. Sometimes you know fully that what’s most important isn’t what’s being said, but what’s happening between the lines. That’s my space: what happens between the lines.”

Arendell draws inspiration from experimental artists like German choreographer Pina Bausch, who is the subject of her next book.

“Pina Bausch was wild,” Arendell says. “She took highly technically trained dancers and put them on stage and had them do movement, such as stumbling, that wasn’t technical at all.”

And, according to Arendell, subverting the audience’s expectations was the point. “She was so conscious of what was expected, and then put up something completely different. It was a critique of what people like to call ‘high art.’”

Photo by Bob Linder

Beyond the ordinary

In many ways, performances that don’t conform to expectations connect with another of Arendell’s research areas: disability studies.

Someone who is living with a disability may experience the minutiae of day-to-day life in ways that are profoundly different from the majority of the population. When performers are free to venture outside expected theatrical norms, they can shift the perspective of audience members who don’t have personal experiences of disability.

Arendell has explored this connection in two books: “Performing Disability: Staging the Actual” and “The Autistic Stage: How Cognitive Disability Changed 20th Century Performance.” Her perspective is grounded in the idea that disability should be viewed as a “facilitating rather than a debilitating experience.”

As she puts it in her writing: “We become richer each time we come to understand these new perspectives, and performance powerfully enables our understanding of them.”

“Even off the stage, in life, people move in space in ways that tell stories. It’s a message that’s communicated with the body.” — Dr. Telory Arendell

For example, imagine watching a play you’ve seen before. But this time, it’s in a language you don’t understand. You could rely on your memory of the story, gleaning additional meaning from performers’ body language and tone. This is not unlike the way someone with nonverbal autism might piece together information that’s delivered through words they find incomprehensible.

Or, another example: imagine a performance where actors contend with props, sets and furniture that are either much too small or much too large – all while trying to perform the play as it was written. This might offer a glimpse of how someone with a physical disability navigates spaces that were designed with only one type of physicality in mind.

And these are just a few instances of how experimental performances, the “wild stuff” Arendell loves, provide opportunities to broaden perspectives. Theater, she believes, is an ideal place to showcase disability as something other than a deficit. It can instead be considered an “extraordinary experience.” Literally, “beyond the ordinary.”

In “Autistic Stage” she writes, “My own work explores how the performing arts have embraced autism as a set of new perspectives that change the way audiences conceive of space, time, personhood, embodiment, communication, and stage or film imagery.”

Photo by Bob Linder

Outside categories

Arendell brings this research into her teaching. In addition to working closely with the disability studies program, she challenges her theater students to think about their work in radically different ways.

“My class ‘Scripting and Performing’ brings in students who have never done performance art or experimental work,” she says. It offers them the chance to re-envision the scope of their talents.

Returning to the pie metaphor, Arendell says, “Their impulse is to scrape along the edges of the pie tin. I pick up the edges that are set to be thrown away and say, ‘This is the heart of what you’re doing. This is where your story lies, where you’re not trying to fix yourself so you’ll fit into an established category.’ I say, ’This can be your category.’”

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Main photo by Bob Linder

- Video by Lucie Amberg

Further reading

Nature’s way of making chemicals

This root is not the only source of rotenone. It is found in plants in North and South America, southeast Asia, the southwest Pacific Islands and even southern Africa.

Research has shown that when humans are exposed to rotenone through injection or inhalation, they develop tremors similar to those experienced by Parkinson’s patients. That’s why its use as a pesticide has been banned in the United States.

“I’m interested in natural product biosynthesis, which is just a jargon way of saying the process by which nature makes chemicals.” – Dr. Matthew Siebert

So is it safe to eat fish that died of rotenone exposure?

“It has to get in your bloodstream,” said Dr. Matthew Siebert, assistant professor of chemistry. “If it’s going through your digestive system, there’s little risk.”

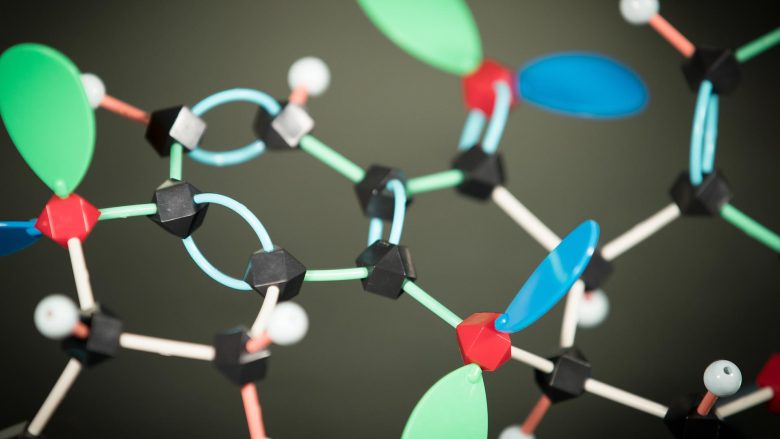

Siebert and graduate student Adam Kirkpatrick conducted a series of experiments to identify the final few steps in the development of rotenone. During this study, which was later published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry A, they concluded there are two ways rotenone is created naturally.

“The way nature makes chemicals – that’s organic chemistry,” said Siebert.

Once you understand how the pieces of a puzzle fit together, it is easier to solve. Similarly, noted Siebert, when scientists make a discovery about how a process like this works, they are able to use that knowledge to develop antidotes for combatting harmful chemicals. His study, he noted, has the potential to assist in the development of new pharmaceuticals to fight Parkinson’s and other disorders.

The barbasco root can be found in the Amazon region.

Fighting cancer

Boeravinone, one of the compounds in the same class as rotenone, has been a focus for Siebert in research experiments. These projects, which he’s conducted alongside Kirkpatrick and Cailin Weber, an undergraduate student, have great potential to help cancer patients who have built resistance to treatment.

“What we are able to say is the way the chemical wants to react is this way or that.” – Dr. Matthew Siebert

“These compounds inhibit that resistance. They knock out that cancer’s defense, which makes treatments that had become unhelpful an option again,” said Siebert.

Since this compound has such profound possibilities, Siebert’s team examined the processes by which boeravinone was created, and the viability of one path over another.

They discovered the most likely path for boeravinone creation was through the use of free radicals. Since free radicals are usually considered harmful in the body – they form due to environmental factors as well as stress, poor diet, stress or smoking – this was a surprising finding.

“As humans, we try to ingest antioxidant-rich foods to get rid of free radicals,” said Siebert. “But there are plenty of human processes that use free radicals, so it was interesting to see that mirrored in this plant.”

To make these determinations, Siebert looks at the type of atoms in the molecule, how many electrons are present and the energy determining factor inside the molecule.

Their studies, he said, are trying to reveal the “energetically favorable thing to do,” or the most likely way a reaction occurs.

When Siebert decided to investigate the very first step into rotenone development, he was surprised: Nobody had ever tried to understand it.

Model representation of rotenone. Photo by Kevin White

Anything but basic

Siebert calls himself an applied theoretical organic chemist, which means you won’t find him concocting chemical brews in test tubes. Instead he’s using quantum mechanics as he’s creating models, providing insight into chemical reactions and carrying out reactions in the virtual world.

“When we publish work, that’s the collection of several hundred individual experiments.” – Dr. Matthew Siebert

“A lot of scientific research these days is done through computer programs and modeling software to help us see what we can’t see with the naked eye,” said Weber. “I like that we are using the forefront of technology to perform research.”

Although it sounds anything but basic, Siebert said it’s, “basic science. It’s like the old saying that says we’re standing on the shoulders of giants.”

In a field that tries to explain natural reactions, it seems that the possibilities are endless.

Biodiesel

People go to local restaurants and pick up used fryer oil to convert to diesel. Since most passenger vehicles don’t run on diesel, it has limited use. But Dr. Matthew Siebert and Zach Wilson, graduate student, presented research at American Chemical Society about how to get gasoline from biodiesel.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

Further reading

A place for meaning

What comes to mind?

Dr. Judith Meyer, a historical geographer, wants to know how you experience that landscape and why.

“I study the sense of place: the meanings people give to the landscape and how those meanings influence our attitudes toward particular places, especially in terms of how we manage them,” said Meyer, geography program coordinator in the department of geography, geology and planning. “Why do we fight over Jerusalem? Is the Ozarks part of the Yankee North or the Dixie South?

“Understanding the sense of place is important in making thoughtful and effective land-use decisions.”

Meyer’s primary research has been on Yellowstone National Park.

“If you look at 200 years of people writing about their experience in (Yellowstone), certain themes are repeated: ‘it’s beautiful, it piques my curiosity,'” Meyer said. “People express appreciation for a government that protects wilderness while also making that wilderness accessible to the public.”

Photo submitted by Judith Meyer

A path to the past

Meyer has extensively researched Yellowstone’s Howard Eaton Trail. The 157-mile, park-encircling trail’s namesake was a dude rancher and saddle-horse trail guide entrepreneur.

The trail opened in 1923, designed for horseback riding. But over time, park visitors’ interests shifted toward hiking.

In 1970, the National Park Service, or NPS, stopped maintaining the trail when park management goals transitioned from providing recreational access to protecting sensitive wildlife habitat and delicate thermal features.

In summer 2014, Meyer traveled with a team of students and colleagues to Yellowstone to hike, map and photograph what remained of the trail.

“I think this research tells us that it is possible to have rich, historically appropriate and authentic experiences in the national parks today as long as you educate people on the significance of what they’re doing, its relationship to the past, its impact on the future.” — Dr. Judith Meyer

Comparing then and now

Photo submitted by Judith Meyer

The group mapped parts of the former trail using Geographic Information System, orGIS, technology, which includes digital images and analysis of the landscape.

Along the way, the group replicated photos from the same vantage points as photos taken on Eaton’s tours. This process, rephotography, provides a side-by-side comparison of the past with the present.

Combining rephotography, historical accounts and GIS technology is a unique aspect of Meyer’s research.

“Photography is really powerful, but there isn’t a lot of good representation of it in the field of geography combined with GIS,” said Emma Walcott-Wilson, a graduate of MSU’s geography program and current PhD student at the University of Tennessee. “Dr. Meyer does an expert job of blending GIS and qualitative research.”

Meyer’s group presented a poster entitled “The Howard Eaton Trail: Crossing Borders and Disciplines to Preserve the Past” at the 12th Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

A section of the poster read: “Rephotography of sites along the (trail) show that little has changed about the traditional Yellowstone experience. People stubbornly return to the same vantage points, endure hardship … and engage in many of the same activities.”

The study’s purpose: preserve the trail as a “cultural, historical and scientific” artifact.

Kortney Huffman, GIS specialist for the city of Springfield, wrote her thesis on the project, completing her master’s degree in geospatial science in 2015.

Photo submitted by Judith Meyer.

Setting the record straight

Meyer’s research on Yellowstone helps clarify history. For example, conventional wisdom suggests Eaton himself laid out his namesake trail.

“Eaton died the year before the trail opened,” Meyer said. “Naming the trail for Eaton was in part a political ploy to bring name recognition to the newly established NPS’s infrastructure project.”

She wrote about this myth in Western Historical Quarterly and about the 2014 field course study in the Geographical Review. Both articles appeared in 2017.

Meyer’s future endeavors include a biography of Eaton and his connection to Yellowstone. Additionally, Meyer plans a book, in conjunction with Huffman, showcasing photo-pairs on some of her best rephotography projects.

Naturally, this research requires a trip or two back to Yellowstone.

“When it starts to green up in the spring, I feel a tug, a pull, to return to Yellowstone,” Meyer said. “It’s a bit like the monarch butterfly or humpback whale migration. I feel called back to the park.”

Inspiring others with geography

Emma Walcott-Wilson was a history major, until she took one of Dr. Judith Meyer’s geography classes.

Her major changed soon thereafter.

“Dr. Meyer was so engaging and passionate,” Walcott-Wilson said. “It was exciting to see somebody that thrilled about what they were doing and excited about their students following along.”

Walcott-Wilson earned bachelor’s degree in geography from MSU, earned her master’s at Mizzou, and is currently pursuing a PhD at the University of Tennessee.

In 2016, Meyer invited Walcott-Wilson to present at MSU’s Geography Awareness Week Seminar.

“Working with Dr. Meyer is something I’d like to do more of in the future, especially because one of my concentration areas is national parks.”

- Story by Kai Raymer

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Making money do the work

“I tackle different areas, but eventually it’s all about proving some of the common sensical insights.” – Dr. Edward Chang

In his view, money may be related to each of these, whether it’s by selecting the right investments, saving money, giving generously or living comfortably into retirement.

These values inform how Chang approaches spreading financial literacy in the classroom and his research.

Chang – who has had nearly 50 publications during his career – researches investment vehicles for the everyday investor. At times, he has evaluated the soundness of Consumer Reports investment recommendations. He has also tested the reliability and risk of newer tools.

Ultimately, he wants to uncover the best ways to make money meet the goals of the investor.

Photo by Kevin White

Tools for investing

He evaluates the characteristics and performance of investment vehicles, or tools used to invest money. These tools can include anything from stock to real estate to mutual funds.

“When you use the wrong approach, it doesn’t matter how much you make,” said Chang. “You may not be able to have a comfortable retirement life.”

Chang, who has been published in the Journal of Investing, has focused his most recent research on exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. These newer investment vehicles are like mutual funds. ETFs pool together investors’ money, and give small investors what only institutional investors could do several decades ago.

“A single person can participate in the pool of money and buy 60 percent of stocks, 40 percent of bonds, for example, and invest the money,” said Chang, an early researcher on this type of investment vehicle. “It’s really a blessing for small investors because they can’t buy a lot of stock with small amounts of money, but in the pool they can.”

“When you try to predict future performance, it’s like the weather – nobody knows.” – Dr. Edward Chang

An investment research firm called Morningstar provided the initial data for his studies, which gave him fund characteristics such as the expense ratio, turnover rate, and risk and performance measures.

From there, he looked at the risk-adjusted return, which he summarizes as being the cure for naïve analysis.

“To see through the fog of risk-return tradeoff, we should focus on risk-adjusted return rather than raw return,” said Chang. “By using risk-adjusted return measures, we are able to determine how good an investment vehicle really is and whether the return is worth the risk.”

ETFs grew out of index mutual funds, noted Chang. His findings reveal that they have many advantages, such as low expense ratio, good tax efficiency, tradability like a stock and very low tracking error in terms of premium or discount.

In addition to evaluating these ETFs based on the risk-adjusted return, he notes that a low expense ratio is reliable.

But no investment vehicle is without flaws.

“When I began looking at ETFs, I got excited about them, and then many in the investing public got excited about them. They grew beautifully to the extent that I think we may have overdone it,” he said. “Many different varieties came out, small niches, kind of like a fad.”

Like fashion fads, he doesn’t expect these small niche funds to perform well in the long run.

Photo by Kevin White

Secrets of good fortune

One of Chang’s goals is to have long-term financial security and happiness – and to pay that forward through education.

According to Chang, the key is to first save your money and then invest for the future.

“I think the most important thing I’ve learned in the past 20 plus years is that saving has been underrated and investing has been overrated,” said Chang. “We always think ‘Well, I should invest in the right thing.’ But I think, more importantly, we should save first.”

“If it’s a right thing to do for the next few years, it doesn’t matter if I wait until tomorrow.” – Dr. Edward Chang

This is practical advice – something that financial practitioners and individuals could easily apply. The practicality of Chang’s research is not lost on his collaborators.

One of his frequent research co-authors, Dr. Tom Krueger, J.R. Manning Endowed Professor of Innovation in Business Education at Texas A&M University, was reading USA Today one morning and had to do a double-take.

Billionaire Warren Buffett was providing insight on financial decisions.

“Mr. Buffet’s advice was so consistent with Dr. Chang’s findings…it was almost as if I were reading advice from Dr. Chang,” said Krueger.

Ultimately, Chang believes that investing should be boring, not dramatic.

For those who wish to dabble in higher risk investments for the potential higher pay-off, he has this advice: “We’re talking about your ability to live comfortably throughout life,” so those risky investments should be limited to 5 to 10 percent of the total investment. “You don’t want to play with fire.”

- Story by Shay Stowell

- Main photo by Kevin White