Archive for February, 2021

Improving the lives of kids with autism

Wandering and bolting are both considered eloping – a term used for leaving an area without permission. It’s a problem behavior, especially for children with autism.

That’s why Dr. Megan Boyle, associate professor of special education at Missouri State University, researches the whys behind this largely understudied behavior.

She’s a board-certified behavior analyst, runs a clinic for children with autism spectrum disorders and prepares the next generation of educators for behavior issues in the classroom.

Boyle dives deep into this behavior.

“Some kids will take off, while others just kind of walk off and wander away.”

She wants to empower caregivers with practical and sustainable treatment options to prevent elopement rather than physically intercepting the child before escaping from view. She also wants to give children an outlet for obtaining the same sensations they seek without leaving the safety of their environment.

“Elopement as a response form hasn’t been acknowledged for how unique it is,” Boyle said. “If we recognize bolting is fundamentally different from a lot of other behaviors we deal with, we can improve how we’re treating it.”

Dr. Megan Boyle works with a young child near the entry of her clinic.

Why kids elope

Boyle’s elopement research identifies the reinforcement children seek by bolting.

“With elopement, you could have four kids who bolt for a variety of reasons,” she said. “So their treatments are all going to look different.”

“I think as a field, we’re kind of missing some nuances about elopement.”

She classifies the reasons as:

- Attention-seeking: Caregivers naturally chase a child who is running away.

- Escaping a task, place or situation: Children with autism often want to escape a specific situation because it may be unfamiliar, unpleasant or overstimulating.

- Sensory seeking: A child may run because he or she enjoys the pounding of the pavement, the strain of the leg muscles or the wind whipping against his or her face.

- Accessing an object or activity: When it’s out of reach, bolting may seem like the only option.

Boyle noted that some kids bolt because they want a nearby object.

“In a waiting room, a kid runs and mom says, ‘Come back and I’ll let you have my phone to play your favorite game,’” Boyle said. “Or it could be a desire to get the balloon they see across the room or street.”

Reviewing the literature and treatment options, Boyle noticed a lack of understanding of these complexities.

“We are considering a lot of variables and aspects of real life that aren’t being incorporated into the research so far,” she said. “Before we can target problem behaviors for treatment, we have to understand the why.”

As a board-certified behavior analyst, Dr. Megan Boyle runs a clinic for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Communication is key

Recently, Boyle published an article on some tactics she used with an 8-year-old client. He eloped to engage in stereotypy, often called stimming in the autism community.

Stereotypy is a repetitive nonfunctional behavior. In the autism community, hand flapping is one of the most common examples.

“A lot of kids with autism engage in behaviors that look a little different. But for them, it provides sensory stimulation or reinforcement,” she said.

In Boyle’s study, the boy was fascinated with hinges and felt drawn to doors. He would open and close the door, look at the hinge, walk through the door, and elope to do so.

Challenges abound in the treatment of severe behaviors, Boyle pointed out.

“How can we develop a treatment that parents will actually use, but that is still effective?”

Prior to each session, Boyle provided pictures of all the doors in the clinic building to her client and asked which one he’d like to play with. After careful consideration, he’d select one.

To encourage functional communication, Boyle would require him to point to it, ask to play with the door and then stay 20 feet away from the door until given permission to play.

“It didn’t count as elopement because he asked and received permission. He would go play with the door for one minute,” she said. “Then we would guide him back to the office and start over.”

The next step was to deny a percentage of his requests – to delay gratification – a procedure called schedule thinning, that is conducted after the communication response is strengthened. Gradually, Boyle increased the effort required or lengthened the wait time before play time.

Learned behavior

You may think, ‘If he could reach the door, why would he ever wait?’

In this study, though, if he bolted without permission, he only received three seconds with the door before removal. The 8-year-old understood he got more time when he waited.

“We’re really good at treating behaviors in the clinical setting, but practitioners often feel much less confident on how to apply those skills in the school or home setting. It’s a next step for me to help others mindfully set up clinical settings to mirror more naturalistic settings.”

“Kids will learn. You have to be consistent and the difference has to be clear,” Boyle said.

Boyle and the client’s mother then tested it in more natural settings. They would chat in various areas around the building, keeping an eye on him while denying or delaying his requests. After many meetings, he began to wait five or 10 minutes surrounded by strangers and doors.

“We use reinforcement so much because it works,” she said. “It changes behavior. Feelings follow. Kids get happy when they can ask for what they want, and they get it.”

And that is her motivation.

“There’s nothing like working with a kid with autism,” Boyle said. “The world melts away. It’s all about improving a life by increasing access to wants and needs.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Reading between the data

This is a question Dr. Seth Hoelscher poses to his students when he is teaching investments and disclosures.

“You’d give money at a better rate to the one you have more information on,” he said.

Hoelscher, assistant finance professor at Missouri State University, was working toward his MBA at West Texas A&M University when the financial crisis of 2008 hit. As many people lost money during the recession, he decided to learn as much as he could about finance and investments.

Now he teaches the subject while researching commodity markets, disclosures and corporate finance. In 2019, he received the College of Business award for Best Empirically Based Research Paper. He’s published over 19 articles and written financial advice for sites like WalletHub.

What influences investors

Many of Hoelscher’s articles focus on voluntary disclosures. Such disclosures involve a company releasing information beyond the requirement of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Disclosures include information about a company’s financial operations. They can include both positive and negative news, data and operational details that affect business. Investors then use this information to shape their expectations for a company.

“We try to solve answers in the literature.”

Hoelscher pairs standard empirical data with hand-collected data from financial disclosures to determine what certain industries do and do not disclose voluntarily.

“Disclosures tell us how the company is operating and if or how they are managing risks,” he said. “It also tells the investment community more about the future prospects of the industry as a whole.”

The information helps investors understand a company’s future cashflows and profitability. This knowledge ultimately affects where investors put their money.

Disclosures also can positively affect a company’s reputation in the marketplace. This usually translates into increased market share and customer loyalty.

For example, consumers who know why prices go up and down in certain industries may feel better about investing in certain companies within those industries.

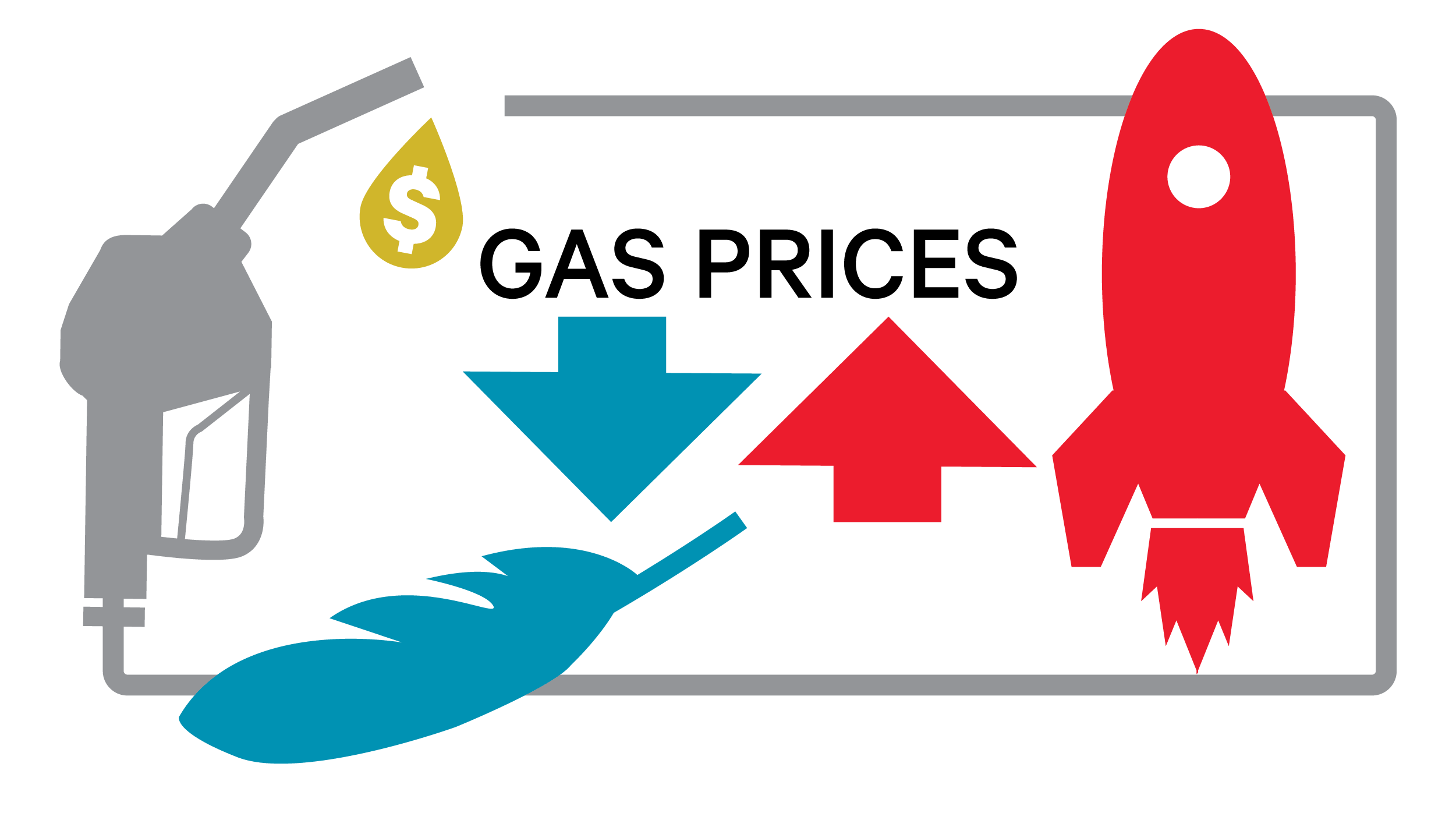

When oil prices rise, gasoline prices skyrocket. When oil prices drop, gasoline prices drop slowly, like feathers.

Rockets and feathers

One industry Hoelscher studies is petroleum and crude oil.

He surveyed literature to assess how petroleum prices respond to increases versus decreases in oil prices.

“This is a phenomenon referred to as ‘rockets and feathers,’” he said.

When oil prices rise, gasoline prices rise quickly as well — like rockets — to reflect the change in prices. However, when oil prices drop, gasoline prices drop at a slower rate — like feathers.

“One item that makes the oil and gas industry unique is the large up-front capital costs to find, drill and extract the crude oil,” Hoelscher said. This affects supply, but not demand, which can create interesting price fluctuations.

For example, in 2020, COVID-19 caused a significant and prolonged downturn in oil prices.

“While reduction in travel and increased remote work didn’t affect the supply side, it did affect the demand side,” Hoelscher said.

Large price swings in an industry like this may lead to questions of speculation and price manipulation.

“You cannot simply increase or decrease crude oil production in the short term to match the current demand. It is not like turning on and off a faucet.”

However, the empirical evidence Hoelscher surveyed shows speculation does not increase volatility in petroleum product prices.

“Ultimately, consumers can feel assured that speculation is not driving changes to the price they are paying,” he said.

Asking the right questions

Financial research presents unique difficulties. Most researchers use the same databases to collect their information.

“You have to ask, ‘how can I go about answering a question that hasn’t been answered? Or how can I answer a question from a different perspective?’” Hoelscher said.

He emphasizes this process when advising students at MSU.

“It’s great for students to learn how to justify their assumptions when presenting reports and research,” Hoelscher said. “Because it’s something that they’ll most likely continue to do in their careers.”

Hoelscher knows he will have to continue asking the right questions to find new perspectives in his work.

“Because it’s a social science, you can’t control every aspect,” he said. “But you can be creative to come up with new ideas and approaches.”

- Story by Kristina Khodai

- Photos by Jesse Scheve