Archive for 2023

How studying what we like can show us who we are

The cultural juggernaut aired on NBC for seven seasons, amassing a loyal fanbase and living on in pop culture fandom. The show spawned countless memes, inspired young girls to go big, launched Galentine’s Day into the national lexicon and continues to live on in rerun glory.

Dr. Holly Holladay, associate professor in the department of communication, media, journalism and film at Missouri State University, knows all about the cultural “treat ‘yo self” movement, who “Mouse Rat” is and why March 31 is significant. Holladay is the author of the book “TV Milestones: Parks and Recreation.” The political satire sitcom follows the antics of public officials in the Parks and Recreation department of Pawnee, Indiana.

“This show is reflective of a culture in transition, both in terms of the television landscape, media and what media do. There’s no better time capsule for understanding that period between 2009 and 2015 than Parks and Rec.”

Why Parks and Rec

“Great job, everyone. The reception will be held in each of our individual houses alone.” – Ron Swanson

Holladay researches popular culture – specifically popular media, more specifically television, most specifically user engagement. She earned her master’s degree at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. The irony is not lost on her. Parks and Rec’s fictional Pawnee, Indiana, is based on Muncie.

Parks & Rec debuted right as streaming threatened to limit the wide fan appeal of traditional broadcast. Sitcoms had to adjust. Preceding shows, such as “The Office,” began to break the sitcom mold by forgoing the laugh track and using single camera mockumentary style shooting. Holladay said Parks & Rec hit at the right time and blew it out of the water. And in so doing, not only changed the sitcom landscape, but helped Americans through a time of transition.

“It created verisimilitude, which basically just means a sort of realism, a sense of being true.”

Parks was also serialized. Holladay said yes, you can watch a one-off episode and laugh, but to fully understand you must watch them all. And fans did — in droves. In 2019, “Parks and Recreation” was ranked 54th on The Guardian’s list of the 100 best TV shows of the 21st century.

Holladay said another shift away from the traditional sitcom was marketing and production focus on engaging fans beyond the weekly episode.

“You’re thinking about how to build hype before, you’re thinking about how to engage people during and you’re thinking about how to keep them coming back after,” she said.

This all translates into auxiliary content produced by NBC and adds to the fervor of shows. For Parks specifically, she points to a fully fleshed out Pawnee government website filled with show Easter eggs as a prime example. Because a successful TV show can cover more ground than even the longest film, fans often feel that the characters become family.

“Each week, you sit down with Leslie and Ron and Andy. You laugh with them, and you cry with them. That means something to people.”

Why pop culture

“I have no idea what I’m doing, but I know I’m doing it well.” – Andy Dwyer

Holladay describes pop culture as an accessible reflection of our society.

“Sitcoms have historically been sort of denigrated, sort of lowbrow,” she said. “But Parks was us. It was ripped from the headlines.”

The series run is contained entirely within Barack Obama’s presidency. Holladay argues protagonist Leslie Knope is a bit of a proxy for Obama–era optimism.

“She is a relentless public servant. She believes in that,” Holladay said. “If you match that up with, especially Barack Obama’s early presidential rhetoric and campaign in 2008, it’s all about hope and change.”

As the series progresses, the challenges Knope faces run parallel with Obama’s presidency.

“There’s a gay penguin wedding in the second season that is super reflective of the Defense of Marriage Act debate when it was being waged in the Supreme Court,” she said. “And a famous bailout episode, where a local video store is going under and gets help — indicative of the corporate and automotive bailouts of the time.”

Holladay devotes much of her work to studying fan reaction. Character leads Knope and Ron Swanson are diametrically opposed. Holladay said it’s an ideological complexity that echoes society — you view that episode very differently depending on the person you identify with.

“I think that’s part of what makes it, the way that it works itself into everyday life,” she said. “It’s fun and it’s a joke we can understand. That makes us think, even if we don’t realize it’s happening.”

“You can use popular culture as a mechanism to understand so much about what’s going on in our world.”

Why it matters

“Hey Leslie. It’s Leslie. Hang in there. I love you. Bye.” – Leslie Knope

Holladay’s book is part of a series at Wayne State University Press called TV Milestones — including the likes of such shows as “Mad Men,” “The Good Place,” and “Breaking Bad.” While Parks & Rec is her largest project to date, Holladay’s research into a number of titles has led to numerous publications.

Chandler Classen, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has written multiple works with his former professor.

“Our first article together was about ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and audience engagement with the show. I was a very young scholar then and [Holladay] guided,” he said. “Right now, we are working on an edited book collection called ‘Television Sitcoms and Cultural Crisis.’ It kind of started with a shared love of the TV show ‘The Last Man on Earth.’”

For Classen, Holladay is more than just a writing partner, she helped him process the realities of graduate school and further his own research.

“A lot of teachers expect their students not to care and organize their classes and material around trying to convince their students to care,” he said. “Holly gets students to care simply by the fact that she cares so much.”

Holladay understands exactly where Classen is coming from.

“I wanted my research to do something important. I would argue people do not perceive popular culture as important. It’s just entertainment. It’s just fluff. It does not matter. I come at it from the perspective is that it matters profoundly because there is nothing we engage with more. Sometimes mindlessly, sometimes actively, but definitely every single day.”

Further reading

- Story by Emily Letterman

- Photo by Jesse Scheve

Counting shapes for the future

On a hot summer day in Hanoi, Vietnam, colleagues toss ideas back and forth. There are drawings on a chalkboard. Concepts bounce off each other. Rules bend, break or are cast aside entirely. Ideas that aren’t working are shelved in favor of exploring more solid options. Finally, a creative breakthrough. Clearly, this is a room full of mathematicians.

Steven Senger, associate professor of mathematics at Missouri State University, spent the summer of 2023 at the Vietnam Institute for Advanced Studies and Mathematics in Hanoi. There, he worked with colleagues from around the world.

“Think about mathematics research the way you might imagine songwriting,” said Senger. “There are rules, but it’s a very creative process.”

Senger wants everyone to understand that the process mathematicians use to unlock equations shares a lot with the process a film editor or a choreographer uses.

“People say ‘but there are rules and there’s an answer at the end.’” Senger said. “Yes, but also no.”

“Sure, there are rules governing the narrative arc, right? But if you intentionally break the rules, that can also be valuable. And people intentionally break the rules in mathematics all the time.”

In fact, breaking rules in math is a common occurrence. Sometimes, broken rules lead to new mathematical discoveries, culminating in published research.

Using shapes to map data

“I have the easiest research to explain,” Senger said. “Okay, you ready for this? I do geometric combinatorics. That means I count shapes.”

Imagine a plane full of dots, like a giant sheet of graph paper. Drawing lines between the dots creates shapes — squares, rectangles, triangles. Now, imagine you want to know all the shapes contained in these dot-to-dot connections. More importantly, you want to know all the repeating patterns that exist among the dots. Senger’s research unlocks how mathematicians create algorithms to find this answer.

Senger’s research is abstract. The applications of his research, however, are no longer simply theoretical.

Imagine that the graph paper is a floating field of drones, hovering over a quickly escalating forest fire. Using ideas from Senger and his colleagues, fire response teams can send a network of drones into a forest fire. The drone network collects data to determine where the fire is burning hottest, which helps the team form a plan for extinguishing the fire. This research has potential applications wherever people need to quickly collect a lot of data in a place that isn’t safe for humans, such as oil spills or chemical plumes.

The research has artistic purposes, too, like drone shows used to light up sporting events and city skies around the Fourth of July.

So, when Senger “counts shapes” he is really looking for geometric patterns in big data sets. Those patterns and shapes create a structure to take in a lot of information in the form of sensor networks. They also have applications in robotics and computer science.

One of the collaborators Senger works alongside is Eyvindur Ari Palsson.

Palsson said Senger “is at the forefront of understanding how the complexity of the pattern impacts these questions.”

Small advancements add up

Math discoveries can take a long time. Research moves forward incrementally. In fact, the main research question Senger explores, called the Unit Distance Problem, was originally posited in 1946 by a Hungarian mathematician named Paul Erdős. Erdős asked: How many pairs of points in a set of “N” points could be at a specific distance from each other? Another way of asking this is: how many times can a shape or pattern repeat in a big data set of points?

When Senger was in grad school, he unlocked one part of the puzzle. He published it in his dissertation. Years later, some colleagues contacted him when they figured out how to expand on Senger’s research. The three published their research in the Journal of the London Mathematical Society.

Senger collaborates with mathematicians across the globe to work on these studies. It is another way that he says math feels like an inherently creative process. In a globally connected field like math, people around the world work independently to move an idea forward, then come together to share their findings.

Learning from students

Other important collaborators in Senger’s research are his students. Caleb Marshall did an independent study with Senger. Marshall, not originally a math student, had to dive into Senger’s research headfirst. Marshall’s fresh set of eyes helped him identify new, creative solutions. At first, Senger was concerned that Marshall wasn’t understanding the concepts.

“I just kept saying, ‘No it’s going to fall like this,'” Senger said. “And he just didn’t get it…until eventually I realized it was me who didn’t get it. Caleb was right and I was wrong.”

Together, along with fellow math department faculty member Shelby Kilmer, they unlocked another part of the dot product puzzle.

Marshall describes Senger as “the kind of mentor and collaborator that can inspire an entire career’s worth of imagination and passion for mathematics.” Marshall also notes Senger “is, at once, both a seasoned researcher and writer, and manages to remain approachable and friendly with his students.”

Shaping the future of dot product research

Senger’s work has the potential to extend to places he hasn’t even thought of yet. Senger thinks the study of dot products has the potential to improve existing artificial intelligence algorithms — or even help create new ones.

“I’m just excited by the idea that people could understand things, you know?” he said.

Further reading

- Story by Katherine Whitaker

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Uncovering the truth and the trauma

When Dr. Marnie Watson’s career as a novelist didn’t pan out, she sought a new path where she would unveil truth about humanity and culture.

As a cultural and medical anthropologist, Watson immerses herself in her research, where she draws close to people in extreme circumstances. She asks questions to better understand, “how they deal with life in difficult situations.”

Much of her work has dealt with illicit drug use, mental health, poverty, homelessness and involuntary migration.

In 2022, she finally realized her dream of publishing a book – this time, about one of her research projects.

A moving career

Watson, now an assistant professor of anthropology at Missouri State University, characterizes her jump into this field as naïve.

“I was completely out of my depth,” Watson said.

It was fortunate, though, that as a graduate student, her advisors saw potential in her. Immediately, her research led her to meet individuals with behavioral health issues.

Those early studies showed her how meaningful the work was but also how emotionally taxing it would be.

“There were days I went home and I would tell my partner, ‘I made every single person I talked to today cry.’”

She also found that trauma serves as a common breeding ground for substance abuse.

“One hundred percent of the people I studied had suffered horrific trauma in their backgrounds,” she said. “That shifted my perspective on mental health and substance abuse.”

These experiences prepared her for a study with Nepali/Bhutanese refugees who were resettling in Akron, Ohio. This research is chronicled in her 2022 book with Dr. Pritha Gopalan, director of research and learning at Newark Trust for Education.

The head of social services at a local refugee resettlement agency, Radha Adkihari, reached out to the University of Akron, where Watson was teaching at the time. Adkihari asked for assistance in understanding one primary question: Why are there so many cases of alcoholism or alcohol-related injuries in the Nepali/Bhutanese refugee population?

“They said, ‘We’ve never seen anything like this. This group is off the charts,’” Watson said. “They were seeing advanced alcoholism in little old ladies, a lot of domestic violence, terrible car accidents and a lot of DUIs.”

Looking into the refugee experience

To prepare for this anthropological study, Watson first had to soak in the history of the Nepali/Bhutanese refugee camps established in the 1990s. At that time, many fled Bhutan due to an oppressive government. They sought asylum in Nepal.

“These people were in refugee camps for 20 years before they were resettled to the United States,” she said.

It’s not as simple as relocating families in the U.S., Watson noted. The government resettlement program doles out funds and assigns groups to settle in these designated locations, at times breaking up extended families in the process.

Watson advocates for preserving extended families in the resettlement process. Through intact kinship systems, refugees coordinate elder- and childcare, transportation and employment. These relationships also provide financial, psychological and emotional support, which are crucial for community and social integration.

To address the question of substance abuse, Watson enlisted the help of an interpreter – Santa Gajmere, who Watson called “a cultural broker” – to better communicate with these individuals.

The more they spoke with the people and learned about their heritage and situations, the more they realized the incredible diversity among the Nepali/Bhutanese refugees. This included multiple languages and dialects, religious differences, as well as caste and class differences.

“The resettlement program is causing a lot of trauma. Refugees have their original trauma from the events that led them to being refugees, and this whole set of traumas that came from living in the refugee camps. Then they were traumatized again when they were resettled to the U.S.”

Within those categories, there were different relationships with alcohol, too – some of which distinctly prohibited drinking.

A voice for the voiceless

While offering a resettlement program seemed like a humanitarian effort, Watson found parts of the program itself and the dispersal policy in particular problematic. Many individuals were isolated from their support systems, had difficulties integrating in the community and struggled to find meaningful work.

Ultimately, Watson discovered the program was part of the cause of the trauma that led to substance abuse issues.

“There are layers of trauma that accrued over time,” Watson said. “While you’d think that resettlement might be a purely positive experience, the way it is often done causes additional trauma. That is what people more often would talk about.”

Gopalan applauds Watson’s fieldwork, empathy and commitment to equity. The flaws in the system exposed in this study could easily be avoided, she noted, if people with direct experiences as refugees were included in the development of solutions.

“Their perspective is rich, layered and steeped in their experiences,” Gopalan said. “By employing strengths-based perspectives and discourse, we benefit from the refugees’ experiences and ideas, rather than patronizing them or casting them as helpless victims.”

Happiness in a small community

In Springfield, Missouri, Watson works with the previously unhomed at a tiny house community, Eden Village.

“Eden Village is built on the housing-first principle, which means, ‘Come with all your problems. You don’t have to sort anything out ahead of time,’” she said. “Once you’re housed, everything is easier.”

Watson is assessing whether residence at Eden Village improves quality of life.

More than that, though, she’s getting the insider view to understand the worldview of community members, which is what all true anthropologists do. She participates, observes and asks questions to get a deeper and more well-rounded perspective.

Telling the stories of the people she studies has fulfilled Watson’s purpose of uncovering universal truths – something she once thought possible through a career as a novelist.

“A little bit of anthropology is good for you,” she said, “because it is the ultimate study of how you are not the center of the universe.”

Further reading

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Defying expectations: Scripts inspired by extraordinary circumstances

From a young age, Cristina Pippa felt emboldened by the power of storytelling. She wrote and performed plays for any captive audience, even when her puppy was the only co-star.

In more recent years, she developed a talent scripting for screen and stage. Her resume now boasts more than 30 theatrical productions.

“For playwriting, the writer must convey so much through dialogue and action. The audience’s attention can’t be directed by a close-up,” said Pippa. She’s the graduate program director of Missouri State University’s MFA in dramatic writing and screenwriting certificate programs. “So even for screenwriting, I’ve always leaned on dialogue, but I like to write between the lines, too.”

Telling a fully developed beginning, middle and conclusion of a story arc within the confines of 20 minutes is the challenge short film writers must tackle.

“I think specificity is really important in a script. You can really see the details and feel like you are welcomed into their world.”

Pippa has excelled at that. For her 2022 film, “Unmanned,” she won top awards at five film festivals, including Best Direction and Best Narrative.

“Cristina comes up with these amazing notions,” said Kate Torgovnick May, a lifelong friend and writing group companion. “She decides, ‘I’m going to write a play about a family that switches places with a 1950s PSA.’ ‘I’m going to do a musical about the star of the high school musical who’s been murdered.’ ‘I’m going to do a young adult spin on ‘Lady MacBeth.’

“And then she actually does it, in a process that, from the outside at least, seems very swift and effortless.”

Thrilling collaboration

“Unmanned” was born out of creative coincidence.

Pippa was circling the idea of a female drone operator character for a future project she had named “Unmanned.” When Pippa ran into Jonathan D. Mabee at an industry event, he mentioned he had been conceptualizing a military story incorporating unmanned aerial vehicles.

Together, Pippa and Mabee wrote “Unmanned,” which Pippa called, “edgy, kind of dark, but also really fascinating.”

The collaboration showcased Mabee’s military experience and familiarity with its situational jargon. “Unmanned” also underscored Pippa’s ability to write and direct vulnerable and complex characters.

“What draws me into a new project is possibility. What could happen?” asked Pippa. “I love finding a character – whether it’s inspired by a real person or a job – who defies expectations.”

A moral conundrum, existential questions and life-altering choices are central conflicts within the script. Each scene raises the stakes for the protagonist.

Throughout the film, viewers see a bird’s eye view of the lead character running away from an unknown force, building a sense of foreboding.

“I liken it to a waking nightmare,” Pippa said. “We show her anxiety ramping up, then cut to this drone footage, adding to that feeling of being watched or targeted.”

Filming on and around the Missouri State campus, and including alumni, faculty and students in roles both on screen and behind the camera, simplified the filmmaking process, even in the difficult filming season of COVID-19.

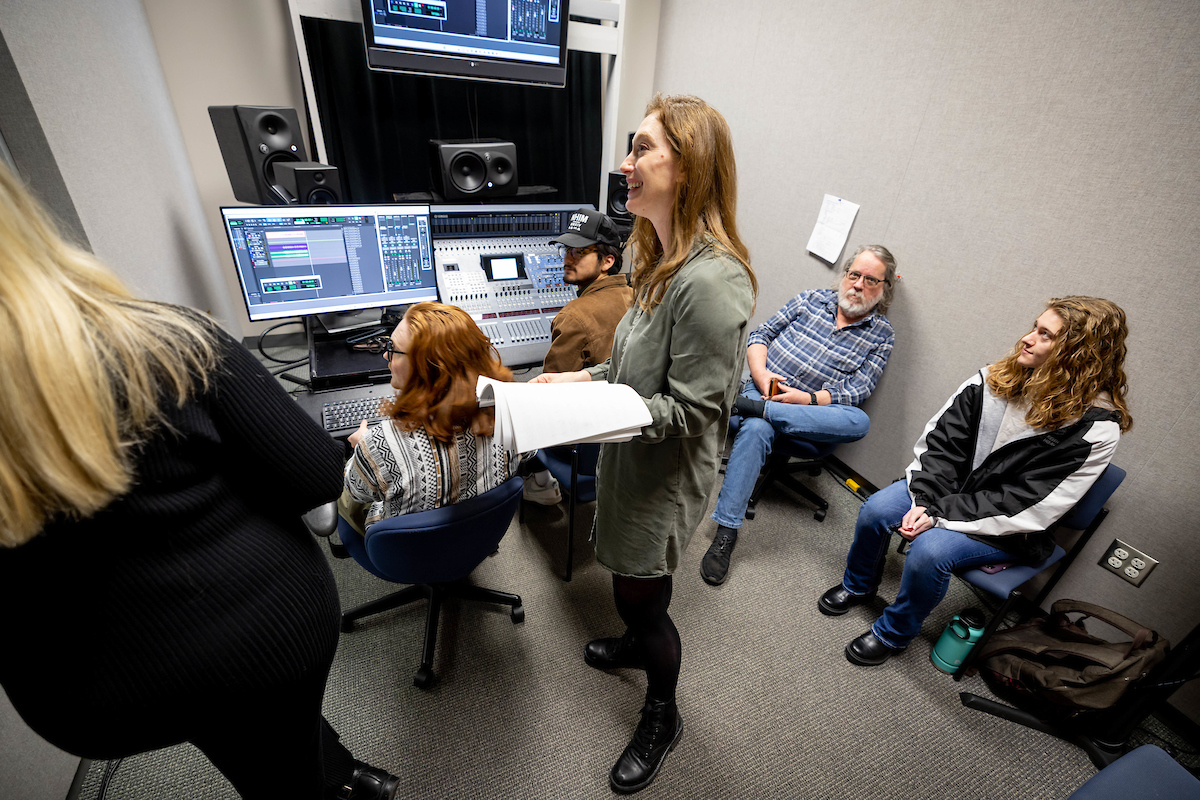

Cristina Pippa and Sharon Kenny work with film journalism students and listen to auditions from singers from theater and dance in Strong Hall on March 3, 2023. Kevin White/Missouri State University

Finding a voice

“The incredible situations women are put in continue to draw me in,” Pippa said, whether that’s a stressful military scenario or pivotal moment in history.

This specificity is one of the top lessons she teaches her students. She also believes it helps set her work apart.

“I want it to feel like you’re watching something that you’ve never seen before or that it’s a day unlike any other,” she said.

In Pippa’s short film “Amelia,” a preteen girl with polio sits at the center of the action. The character hears a distress cry from Amelia Earhart on the day of her infamous disappearance.

“I tend to hear a story or learn about something real, then let it be a seed for the bigger tree that grows out of it.”

The character then builds a short-wave radio to broadcast that message to the world.

“The film toys with this idea of a young, vulnerable girl who is confined to her house due to illness. And it asks ‘what if she finally has a voice herself?’” Pippa said.

“Amelia” was developed for Spark, a series of short films to inspire girls in science, technology, engineering and math. Pippa co-founded Spark due to her personal interest in empowering and inspiring young women in all fields.

At the 2018 Mumbai Film Festival, “Amelia” won the Gold Gateway Award for Best Short Film and was the official selection of the Toronto International Film Festival.

It’s a highlight of Pippa’s career.

“She doesn’t just have the ideas,” Torgovnik May said. “She gets her butt in the seat and writes it. She has just an embarrassment of riches when it comes to great, completed projects.”

Cristina Pippa and Sharon Kenny work with film journalism students and listen to auditions from singers from theater and dance in Strong Hall on March 3, 2023. Kevin White/Missouri State University

Further reading

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Save one to save them all

There are laws in place to hold businesses accountable. But our interpretation of these laws can have unseen consequences.

In 2017, the Trump administration altered the legal interpretation of the word “take” under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, creating a legal debate.

Dr. Carol Miller, distinguished professor of business law at Missouri State University, found this new interpretation placed the lives of countless birds at risk.

One word, many interpretations

Miller disagreed with the 45th administration’s decision. So, she started researching.

Under the act, you cannot ‘take’ a bird. This means you cannot poach, capture, sell or purchase migratory birds or their parts. This includes feathers, nests or bodies in the U.S., Miller explained. The law also applies to the accidental killing of birds.

“The Trump administration changed an interpretation that dated back to the 1980s, which included taking a bird unintentionally,” Miller said. “They decided to stop requiring businesses to seek a permit for incidental or unintentional harm they may cause.”

Businesses were more cautious when required to obtain ‘incidental take’ permits for birds they might harm.

“Without an explicit rule, businesses likely won’t make the effort to protect migratory birds,” she said. “It’s not profitable to be cautious.”

Miller’s paper was published as part of her involvement as a member of the Endangered Species subcommittee of the Environment, Energy and Resources section of the American Bar Assocation.

She has more than 50 publications in academic journals and has received over 25 awards recognizing her research. She has received three MSU Foundation Excellence in Research awards, the MSU Public Affairs award and the MSU Foundation Teaching Award.

One animal and the ecosystem it protects

Miller’s current research surrounds the Dusky Gopher frog and a tortoise with a knack for burrowing.

In Mississippi’s long-leaf pine forests, the frog and around 300 more animals take shelter in Gopher tortoise burrows. The burrows keep them safe from fires, floods and other natural disasters.

Long-leaf pines have been largely logged and replaced by other types of pine trees that grow faster and closer together. The frog and tortoise need the long-leaf canopy to survive.

The frog is an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. The tortoise is listed as threatened in some states but is not federally protected.

“You have to preserve the keystone animal, like the tortoise, in the ecosystem for the rest of its members to thrive,” Miller said.

“There are countless species waiting to be added to threatened or endangered lists. But the cost and personnel needed to protect the species precludes listing all of them.”

Miller hopes this research can show how protecting one key animal can conserve many threatened species.

Her article discusses a proposed regulation that would allow the introduction of some endangered species outside their historical habitat. This research will be published in a 2023 issue of the University of Oregon Journal of Law and Litigation.

At Missouri State, Miller collaborates across colleges to offer environmental law courses to students with concentrations in legal studies in business, sustainability and graduate programs.

Actions and reactions

In 2021, the Biden administration rescinded the ruling that allowed for incidental ‘takings’ of migratory birds. A court decision also overturned the Trump interpretation as being “arbitrary and capricious.”

“This is the nature of administrative regulations. One administration can reverse the policy of a prior administration, but the notice and comment process take time,” Miller explained.

“Legal research wouldn’t be very exciting for most people because it can be tedious,” she added. But this research can help us advocate for better decision-making.

Miller was serving as President-elect for the International Academy of Legal Studies in Business meeting when she met friend and co-author, Bonnie Persons. Persons is an associate professor at California State University-Chico and a practicing attorney in business and corporate law.

They found a shared passion for environmental issues and began researching together.

“When we met, I was struck by her enthusiasm and breadth of her knowledge, insights and expertise on current environmental issues,” Persons said.

“Dr. Miller stands apart with the depth, detail and passion for the issues about which she writes.”

Further reading

-

- Story by Meredith Gale

- Photos by Kevin White

Children’s books for change

But many children’s books do not portray Native Americans accurately. As a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, Lewis is particularly passionate about spreading awareness of Native American history.

“So many books depict Native Americans with the same stereotypical characteristics and misconceptions. Meanwhile, they ignore the unique customs and traditions of over 550 federally recognized tribes,” said Lewis, associate professor of literacy at Missouri State University.

Children’s books often depict the lives of natives from more than 200 years ago. But these books omit the history of atrocities they faced and their rich modern culture.

“As recent as the 1970s, boarding schools took our children from us and tried to force them to adopt Anglo-American values and traditions,” she said.

“These schools used the motto, ‘Kill the Indian, save the man.’ It was terrible, and people often aren’t aware of it. It’s going to take generations for that pain to subside.”

Dr. Kayla Lewis, professor of reading foundations and technology, teaches RDG 318, Foundations of Literacy and Instruction, on February 21, 2023. Jesse Scheve/Missouri State University

The search for honest books

The lack of proper education about native heritage contributes to racism and reinforces stereotypes.

“Children’s books can help combat these issues by providing an outlet for teachers to honor, support and teach native heritage,” Lewis said.

“They can also help preserve endangered indigenous languages.”

She partnered with her former professor and longtime friend, Dr. Sarah Nixon, another MSU literacy professor. Together, they curated a collection of books for teachers to use in their curriculum.

“Children’s books can teach kids about our sovereignty, our people and the differences between the tribes.”

The duo evaluated 95 children’s books from their personal and local libraries. The books were fiction or non-fiction written by or about Native Americans.

They only examined books that they believed were high-quality. They looked for books that:

- Accurately represented native heritage.

- Incorporated indigenous languages.

- Featured contemporary indigenous peoples.

They found a majority of the 95 books would be approved for classroom use.

One of her favorite books they analyzed is “We Are Still Here! Native American Truths Everyone Should Know” by Tracy Sorrell.

“I love this book because it teaches about our true history and shows Native Americans as we are in the present day,” she said. “It shows that even though all these cruelties happened to us, we are still here.”

Lewis found the accuracy of children’s literature has improved throughout recent years.

“Recent authors pay more attention to the nuances of native heritage. They understand the significance of seemingly minor details, so they avoid changing them,” she said.

Lewis hopes the books they identified will provide a better understanding of native heritage for children.

Their research was published in the journal Language Arts in January 2023.

RFT Professor Kayla Lewis with books she reads at the end of each of her classes. February 23, 2023. Jesse Scheve/Missouri State University

Beyond pictures and stories

Children’s books help children learn valuable life skills. This could include the ability to talk about culturally sensitive subjects.

“Part of my work is teaching others how to ask questions and talk about these often-taboo topics,” Lewis said. “People can be so worried about offending others that they avoid conversations altogether.”

“Asking questions is a great way to learn about other cultures, and many people are open to teaching others about their cultures.”

But these conversations are necessary to combat stereotypes and learn about others.

“We’ll see kids grow up not afraid to talk about these things. They’ll be more understanding, accepting and willing to be the agents of change we need.”

Children’s books also expose kids to different cultures, especially in schools that lack diversity.

“Exposure to a variety of cultures is crucial to create an accepting and educated society,” Lewis said.

“We need a diverse and accurate book selection that represents all students. Everyone deserves representation.”

Part of a larger mission

Throughout her career, Lewis has worked to break stereotypes and educate others about native heritage.

“When Kayla was an elementary teacher in Republic, she often borrowed multicultural books from my collection to read with her students,” Nixon said. “She frequently taught her students about Native Americans and her Chickasaw Nation.”

Lewis and Nixon have collaborated on several projects about multicultural literacy. They plan to evaluate other literature and analyze their diversity course curriculum.

Researching children’s books is only a fraction of Lewis’ plan to better educate the world about Native American heritage.

“Despite her busy schedule, Kayla always finds time to speak to others about what it means to be a Chickasaw woman. She stresses the importance of learning through contemporary examples instead of historical figures.”

Dr. Kayla Lewis, professor of reading foundations and technology teaches RDG 318, Foundations of Literacy and Instruction, on February 21, 2023. Jesse Scheve/Missouri State University

Further reading

- Story by Savannah Keller

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

From education to protection

This is a question Dr. Gary Webb, department head of animal science at Missouri State University, has been researching for nearly a decade.

Throughout the years, the number of animals infested with internal parasites – or as some call them, worms – has increased dramatically. This is especially true in horses.

Webb hoped to gain a better understanding of how animal owners are reacting to this increase by researching groups of horse owners.

“Through our research, we were trying to get some idea of the knowledge level of the horse owners and determine areas where education was needed,” Webb said.

In response to the parasitic increase, Webb and a graduate student began investigating this issue in cooperation with a small team from Texas Tech University.

Assembling the plan

Webb’s research was based around investigating the fecal egg count of horses owned by different owners. in different parts of the country.

The fecal egg count is a diagnostic test on a sample of horse manure to identify the type and number of parasites.

First, they wanted to look at how different owners treat their horses. Second, they wanted to see what role location plays in horse maintenance and health.

“Different groups of owners take care of their horses in different ways. The climate in which a horse is living also has a big effect on the number of parasites they get and how long they live,” Webb said.

Webb’s team identified three groups of horse owners: trail riders, horse show participants and college rodeo teams. Then, they began to gather data from these three main groups.

Hitting the road

The team assembled a survey to present to horse owners around the world, and each team member was given a region to conduct the survey.

The 25-question survey included demographics, like education level of the owner, breed of horse and location.

“The survey also included questions like how often you deworm your horse, what products you use and where you get your information,” Webb said.

The surveys were conducted at:

- College rodeos in west Texas, the Ozark Region and southeast Missouri.

- Horse shows in southwest Missouri, West Texas and Oklahoma.

- Commercial trail ride facilities in south-central Missouri with a clientele from the Midwest and all over the country.

They also retrieved a fecal egg sample from the horses in each location. They tested these samples and sent the results back to the owners.

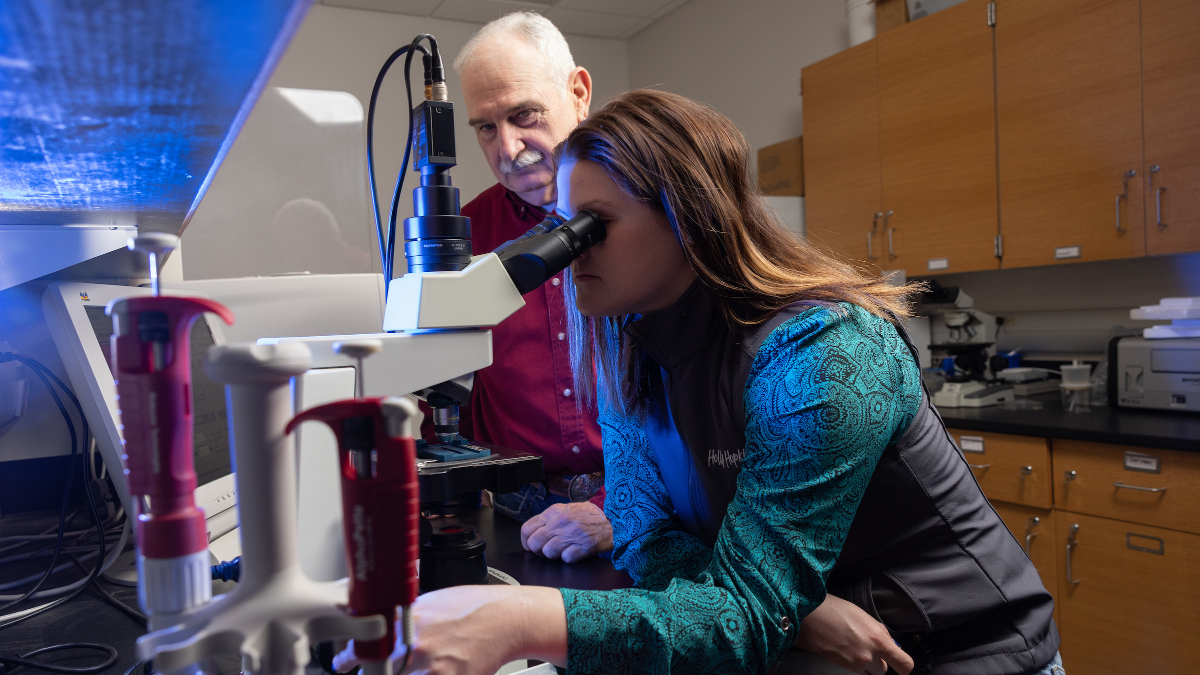

Dr. Gary Webb works with graduate assistant Holly Hopkins in the lab.

Identifying and responding

After months of data collection, Webb and his team analyzed the results.

“We were surprised to learn that the students from the college rodeo and competitive horse show teams weren’t that much more knowledgeable than the general public,” Webb said.

Many of the horse owners were unaware of the type of medicine they were giving their horses. Many owners in their survey said they were rotating the drugs they administered to their horses, but the researchers found they were actually using the same drug with a different name.

“Sometimes they think they’d be rotating trade names but they’re actually the same drug.”

This has become a very common problem since many of the drugs are available over the counter, Webb noted. The survey indicated that 96% of owners administer the dewormer themselves.

But based on the fecal egg count tests, Webb’s team deduced the owners probably weren’t administering the dewormer properly.

“In Europe, dewormers are prescription, not over the counter. There’s a push to be like Europe, which is going to be a tremendous cost. At the same time, there’s a need to use them more judiciously,” Webb said.

Even though the popular press had highlighted this issue in recent years, results showed very few horse owners knew what a fecal egg count test was.

“65% of respondents noted they make their purchasing decision based on the price of the drugs.”

The research team also found an inverse relationship between the fecal egg count results and the owners’ knowledge on this subject.

“We were trying to get some idea of the knowledge of the horse producers and look at areas where they needed some education,” Webb said.

Looking ahead

Webb and his team used these data to show how important it is to address the lack of education for these animal owners and help educate them.

Today, he continues to research and study in the field of animal science and educate those in the industry.

Webb is currently focusing on the process of semen preservation and looking at efficient ways to transport that semen.

“Dr. Webb has generated dozens of publications through his own and graduate student research in equine reproduction, exercise physiology and nutrition that focused upon practical methods to improve the horse industry,” said Dr. Anson Elliot, emeritus dean of Missouri State’s Darr College of Agriculture.

“His more than two decades at MSU has been key in transforming the Darr College into having a highly respected comprehensive animal sciences program.”

- Story by Jonah Rosen

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Pattern recognition enhances biomedical research

Many mathematical processes depend upon this ability to sort information or attributes, and it’s a big part of machine learning, too, according to Dr. Tayo Obafemi-Ajayi.

“The great thing about machine learning is it allows us this discovery of knowledge but also prediction,” Obafemi-Ajayi said.

She is an associate professor of electrical engineering in Missouri State University’s cooperative engineering program with the University of Missouri Science and Technology.

Although her research covers a wide spectrum, it is all tied to the use of technology in biomedical sciences. She designs computational models and algorithms that make it possible for a machine to learn to sort data and predict outcomes — all in hopes of automating processes or improving decision making.

Team building

When evaluating new projects, Obafemi-Ajayi leans on her expertise in mathematics and computer and electrical engineering. She has published more than 10 peer-reviewed journal articles in these fields in the last five years.

“I’m always interested in the real-life problems we are facing,” she said. “I ask, ‘How does that translate to a machine learning problem? And how can machine learning make it better?’”

To improve machine learning, data must be available. Clinical data are usually collected for physicians. Unfortunately, these data may not be what are most useful for a computer, leaving knowledge gaps.

“All of this data we’re amassing, can we put it to use and learn something that will benefit our society?”

That’s one reason she builds domain experts into her research team from the very onset of each project. These experts – statisticians, neuroscientists, neurosurgeons, mathematicians and engineers – work together to design projects, create solutions, validate the process and interpret results. She calls this “no-boundary thinking.”

Dr. Gayla Olbricht, a frequent collaborator and mathematician at Missouri University of Science and Technology, greatly values this model.

“She is very successful at working with medical doctors to help inform useful research questions and to ensure that the results can be interpreted in a clinically meaningful way,” Olbricht said. “I appreciate her openness to learning about new concepts from different experts on the team to strengthen the overall research.”

Giving hope

For physicians, diagnosing and giving accurate prognoses are challenging due to the number of symptoms, demographics and other variables. In disorders like autism, the heterogeneous nature of these variables caused the medical community to classify it as a spectrum disorder.

“For the biomedical applications I work with, we’re not trying to replace the doctors. We’re helping to enhance.”

The nuances of autism drew Obafemi-Ajayi’s interest. From her perspective, a study of autism’s effects would be an ideal place to apply machine learning.

“We were looking for any meaningful patterns that could shed light on what we know,” she said.

Her research team wanted to break up the symptoms into more homogeneous clusters and patterns, so doctors and families could be more informed.

“Parents could have more hope. They could see, ‘These are the types of symptoms my child has, and this is how others in a similar state have developed.’”

And that’s what Obafemi-Ajayi’s team was able to do, resulting in multiple papers on the subject.

Seeing the signs

Similarly, traumatic brain injuries, or TBI, are quite heterogeneous, noted Obafemi-Ajayi.

Her research team discovered that in addition to symptoms and outcomes varying widely, there were even more data sets in TBI. This included clinical labs, imaging data, genetic and demographic information, and blood biomarkers.

While the study focused on TBI, they tackled it with the same goals and similar tactics in mind. They worked to identify subgroups of TBI sufferers, predict outcomes and test the validity and ability of the machine to apply its learning accurately.

For this, they used data from the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research, which the National Institutes of Health maintains. On the initial study, they successfully broke out seven subgroups, driven by the cause of injury and recovery trajectory.

“We’re trying to really see, ‘Can we design stuff and produce meaningful results that have a clinical significance and make sense?’”

Obafemi-Ajayi was surprised by some of the correlations that showed up, though, including how education, age and marital status related to outcome. This spurred on more study in this area.

“From the computational aspect, I didn’t believe these were meaningful data points that could help with prediction,” she said. “But it’s actually surfacing.”

In a related TBI study, her team analyzed blood-based biomarkers of college athletes suffering from concussion. The study revealed some connections, but it was made more challenging because many concussed athletes didn’t have blood drawn immediately after the injury.

“With the biomarkers, some of it turned out differently than what we thought it would show, but it’s helpful to know that. Going forward, there’s no need to spend money on this aspect,” she said.

Influencing where funding should go and advocating for innovative research is important to Obafemi-Ajayi.

“At the end of the day, what you’re trying to do is design a model that can learn to do things intelligently based on observing the patterns of how somebody who knows this has done it,” Obafemi-Ajayi said. “Hopefully, some of our work eventually trickles out of the lab to the bedside.”

Further reading

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Office of Video Marketing

Forced migration and the glorification of cartel culture

These forms of literature reflect unnerving realities of violence and crime, forcing many to migrate to the United States to escape the dangers they face. Some never make it.

Dr. Judith Martínez is an assistant professor for the department of world languages and cultures at Missouri State University. Her dialectical research focuses on the coexistence of neoliberal violence and Latinx literature, film, music, telenovelas and series.

A personal experience escaping violence

Martínez grew up in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico, in an area she describes as privileged as far as safety.

“There wasn’t a lot of violence when I grew up. I could go on the streets and ride my bike,” Martínez said. “But then things changed drastically.”

After earning her bachelor’s degree there, she came to the United States to earn her Master of Arts in Teaching. Then she returned to Mexico to be closer to family and continue her teaching career.

That’s when tragedy struck. She was picking up her son from school and the sound of screams filled the hallways. There was an attempted kidnapping by a local cartel that left four people dead.

Dr. Judith Martinez studies the neoliberal violence that started in Central America and Mexico in the 1990s.

Using personal trauma to guide her research

The experience left Martínez traumatized. She and her family moved back to the U.S., and she earned her PhD at the University of Arkansas.

Since then, Martínez has seen parts of her country overtaken by crime. This elevated her interest in social justice, politics, current events and literature.

“Everything I was reading really appealed to me and why I came here,” she said. “It wasn’t really my choice [to leave Mexico]. I was escaping violence. It was relevant to me because I had lived it.”

This interest led to her research agenda. She studies the neoliberal violence that started in Central America and Mexico in the 1990s.

In 2022, she was awarded the Foundation Award for Research from Missouri State University. Her article, “The Central American Migrant: Mexico, the never-ending border,” focuses on forced migration.

Teaching an understanding of forced migration

“When we talk about immigration, we talk about the border a lot. But I see the whole Mexican country as a never-ending border,” Martínez said.

“We only think about the [physical] border between Mexico and the United States: when they crossed the river, when they crossed the wall or when they jumped the wall. We rarely think about when they cross through Mexico, and what they experience as they travel, which is a never-ending border.”

Martínez shares stories and books and reflects with her students. Now that society is more globalized, it’s easier now than before to understand that what happens in Mexico affects what happens in the U.S. and vice versa.

“In Spanish we have a saying; ‘Cuando los Estados Unidos tiene gripa, México estorduna,’” she said. Or, when the U.S. has a cold, Mexico starts sneezing.

As society becomes more globalized, Dr. Judith Martínez has found students are more understanding of the ways that experiences in one country cause ripples in another.

She explains that literature exposes us to realities that no one talks about, and that ultimately the goal is to want to change that reality and to seek justice and dignity for all.

“These books and cultural texts are windows to seeing a different side of the story. They’re going to hopefully make you want to move to action,” Martínez said.

She teaches several courses on border literature. Ryan Mitchem, a Spanish and psychology student, took Martínez’s Latin American Literature class.

“We talked a lot about forced migration,” Mitchem said. “Martínez really emphasized how immigration [from Mexico and Central America] isn’t a slight decision. A lot of times it’s a life-or-death situation.”

He also learned the phrase “pensar es servir” or, to think is to serve. He said Martínez encourages her students to have a global view when making decisions or dealing with other people.

“You never know what someone’s past is like, and you never know what their situation is,” he said.

Students learn not to contribute to these social problems with stereotypical or negative thinking, but instead to approach them by taking other perspectives into account.

Martínez is motivated to bring to light the reality about migration.

“Everybody talks about how beautiful Mexico is; the Day of the Dead, the Cinco de Mayo dances, the margarita nights, taco Tuesday, Cozumel, Cancun … but why are people coming over in caravans every day? Why are people willing to risk their lives completely to cross into situations that are unbearable just so they can survive?”

Her mission to make visible what was once invisible is what drives her research every day.

Further reading

- Story by Sofia Perez

- Photos by Jesse Scheve