Search results for "durham"

Seeking treatment for brain’s ‘perfect storm’

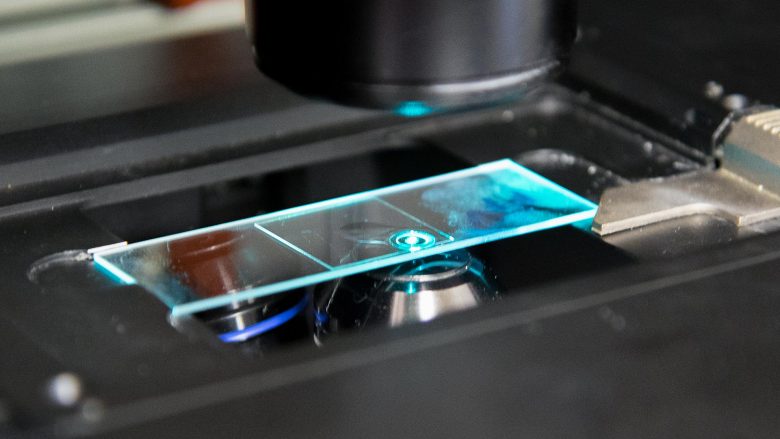

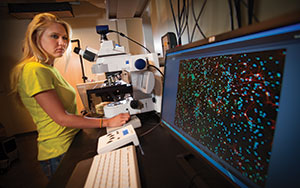

Brittany Thurman, a biology major, uses a fluorescent microscopy to study how new drugs being developed to treat neurological diseases control cellular activity.

A perfect storm: It can erupt at any time if a variety of factors interact just right. Maybe it all starts with a stressful day at work. Although you’re relieved to go home and get work off your mind, you can’t, leaving you with a fitful night of sleep. When you wake, you have a kink in your neck. The morning rolls on, and you juggle your schedule as well as the needs of your household. You step onto an elevator — part of your normal routine — and you take a whiff of strong perfume. Your sinuses are stimulated, and you undergo a migraine attack.

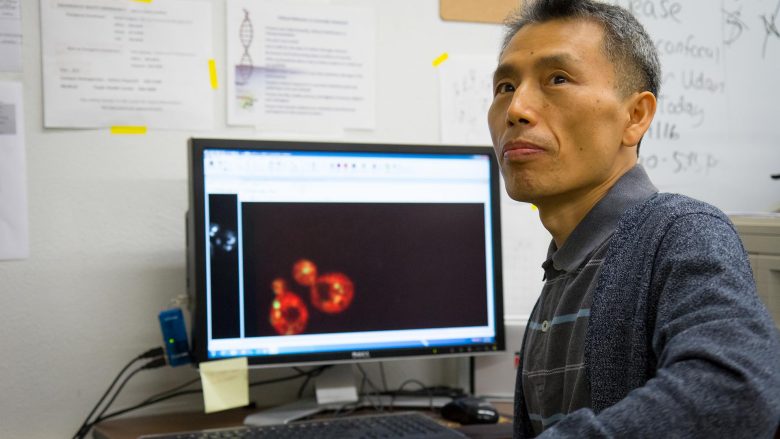

In the world of Dr. Paul Durham, professor of cell biology at Missouri State University and director of the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, that is the “perfect storm” model. In this model, each factor plays a role in making the nerves more hyperactive and sensitive, until one of them tips the balance.

“These nerves begin to do their job a little too well,” Durham said. “Instead of responding to a stimulus in a normal way and alerting you about it, the nervous system response becomes not physiological, but pathological.”

In the early 1990s, during his postdoctoral work at the University of Iowa, Durham became interested in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) — a protein made in nerve cells and known to promote inflammation. As a cell biologist, he was intrigued that increased CGRP levels were correlated with the pain intensity of a migraine attack. Twenty years later, he is an international expert on the study of the trigeminal nerve and orofacial pain.

The trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the head and face, so Durham studies the biological basis for migraines, headaches, temporomandibular joint (or TMJ) pain, jaw pain, toothaches, gum pain, sinus headaches and rhinosinusitis, among others.

His work could have tremendous impact, as studies have shown that approximately 36 million Americans suffer from migraines.

Studying causes of pain, ways to treat it

Graduate chemistry student Geoffrey Manani uses techniques called high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and gas

chromatography mass spectrometry to identify compounds in plant and animal material that suppress inflammation and promote healthy cell activity.

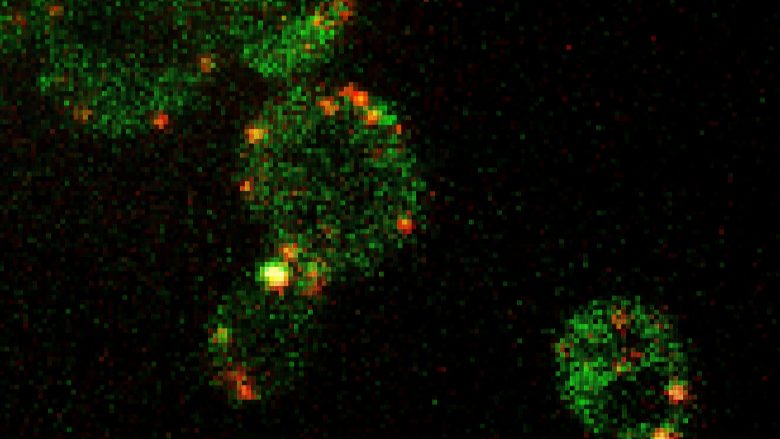

In his lab at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, known as JVIC, Durham researches why nerve cells become hyperactive and why they cause pain. Nerve cells are grown in culture dishes, allowing him and his fellow researchers to see how cells react with various drugs.

During the past couple of years, his research team took their quest for answers one step further: How and why does pain move from acute pain to chronic pain?

“What we’re finding with chronic pain patients is they get themselves in a vicious cycle,” Durham said. “Once they start having pain, they usually don’t sleep as well, which usually causes them more pain. Then they begin to stress about it, and then they get depressed about that. All of these things keep snowballing. Pretty soon you have a system that is out of balance.”

Partially due to his involvement with organizations such as the Society for Neuroscience, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Headache Society, Inflammation Research Association, American Academy of Orofacial Pain and the American Pain Society, pharmaceutical companies often enlist his help in determining the viability and effectiveness of their products. Since JVIC opened in 2007, Durham has been awarded more than $9 million in grants, including funding from pharmaceutical companies and government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health.

“The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results.” — Evan Clark, student

Students of all ages can assist in research

Durham’s laboratory is involved in the identification and characterization of bacteria obtained from medical tissues as well as food products.

As you tour the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences, or CBLS, at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, you may notice how young everyone appears. The approximately 20 researchers in the lab are a mix of full-time employees, undergraduate and graduate students — all homegrown from Missouri State University, Durham noted. Durham holds the only PhD degree in the lab.

“I’ve never looked at undergrads as being any different than grad students,” he said. “If someone is passionate about science and learning, and we put them in the right environment, then they just take off.”

Evan Clark, a senior who has worked in Durham’s lab since 2011, said the CBLS lab has taught him about the design and set-up of medical clinical trials, the importance of teamwork and organization, and the procedures and protocols of research.

Junior biology major Andrew Miller prepares samples for bacterial analysis.

Clark led a menstrual-related migraine study: “The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results,” Clark said. “I am truly appreciative of the opportunity Dr. Durham has given me. His support has made me a better student and person.”

In the last 10 years, Durham has supervised the research of more than 75 students in the CBLS, and says this is one of the best parts of his job: “The students have played a key role in everything we’ve been able to do.”

In the lab, at home, in the classroom or in his downtime, Durham lives to help people — especially youth. As an example, one of his current studies may help eliminate children’s fears of needles.

Instead of using blood as a diagnostic indicator, Durham has studied the effectiveness of using human saliva to look for protein levels, discern what each protein indicates and understand the progression of diseases. Now he’s researching the saliva of a group of neonatal babies and pediatric oncology patients in Utah, planning to develop a diagnostic tool to measure biomarkers in saliva that hospitals and doctors could use instead of drawing blood from children.

JVIC: great resources, collaborations

Jordan Valley Innovation Center, a former milling facility, is a seven-story state-of-the-art research and innovation accelerator. When it opened in 2007, it became the home of CBLS, staying true to its commitment to the development and support of advanced biotechnology industries in Missouri.

Human cancer cells, which can be stored for years in liquid nitrogen, are often used in Durham’s research since they mimic normal human cells.

JVIC is also home to corporate affiliates in the medical, technology and defense industries and the Center for Applied Science and Engineering of Missouri State.

“We have the full complement of all the techniques and equipment that we need in one building, which is really unique,” Durham said. “Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.”

In addition to equipment, Durham said the ability to collaborate with scientists with other expertise has been a huge advantage of being housed at JVIC. One prime example was the development of a “smart” bandage that delivers a drug to promote healthy wound healing.

Starting with a tent material that would decontaminate biological and chemical warfare agents — a product that was developed at JVIC as well — Durham and others at JVIC collaborated through several stages of development. And it was a success.

“It took electroactive polymer chemists to figure out how to put the matrix together, but then you had to have material science people working on how to make a bandage that didn’t stick to the wound. Then you needed electrical current going to the bandage, so you had to have someone who could build an electric device that delivered the right amount of current,” he said. “With the help of Crosslink, an affiliate of JVIC, we were actually able to work with their scientists to develop the product and have it release the drugs that we wanted into the wound to promote healing. We all worked together as a team to make it happen.”

“Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.” — Dr. Paul Durham

Empowering people to prevent disease

The worldwide scientific community collaborated to complete the Human Genome Project in 2003, sequencing the chemical base pairs of DNA to determine the significance of each gene. Since then, research has shown that the average person has 10 genes predisposing him or her to a major disease. Keeping that illness from becoming a reality is another area of research interest for Durham.

Joshua Haydon, junior research scientist, prepares cancer cells to study the effect of a nutraceutical product on inflammatory pathways known to promote disease progression.

“Why are they still healthy? What it comes down to is diet, exercise, good environment and healthy sleep patterns,” he said.

On top of the DNA structure (the genome) is another similar structure called the epigenome, Durham explained. The epigenome, which is responsible for how DNA is packaged and controlling what genes are turned on or off in a cell, can be manipulated through diet, exercise and sleep.

“For example, if you have a ‘bad’ gene that increases the likelihood for a disease, you could completely turn it off for most of your lifetime through epigenetic changes.”

It’s a powerful thing — empowering patients with the knowledge that they have control over a disease. Durham sees nutraceuticals, compounds found naturally in fruits, vegetables and plants, as an emerging field in the next 10 years. These nutraceuticals will be key in a lifestyle plan to keep the epigenome from manifesting certain illnesses.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

“Five or six years ago, we started looking at cocoa and wondered what would happen if you incorporated more dark chocolate in your diet. Would that actually protect you against certain pain pathways? When you incorporate dark chocolate into your diet, you are basically quieting pain-conducting nerve cells. The cocoa modulates a healthy response toward inflammatory and painful events. So the cocoa actually blunts the perfect storm that’s developing.”

Migraine sufferers take heart — clearer days are ahead. Durham and his team of researchers are working to find relief for this debilitating affliction.