By Madeline Hayes, nursing

I saw lights on the east side where people are trying to get back to life. The west side, however, is completely dark.

I heard mortars for the first time that night, and thought “Oh, my word. I’ve never been in this situation before. Are they going to hit me?” But then after a while, you get used to that sound: A shrieking whistle that descends in pitch, followed by an explosion.

It’s normal. That sound is always there. That night, I slept on the roof, and only one thing went through my mind:

“All right, please don’t get hit by mortars.”

Hi. I’m Madeline Hayes and I’m a nursing student at Missouri State. This summer, I spent a month in Mosul, Iraq.

Why I took the trip

I volunteered as a nurse at a casualty collection point (CCP) off the front line. My dad, Tim Hayes, inspired me to go. He’s an attorney in Springfield, was in the Army and got his EMT license in combat first aid. He took six trips in the last two years to Mosul.

I went during all the craziness with the refugee ban, and I saw how upset everyone was. They posted things on social media. I thought, “What good is this doing,” you know? I wanted to do more than that.

However, I just didn’t know when I could leave, because it’s hard to get over there. During finals week, I learned that I could go the following Wednesday. I took my last test in my junior year of nursing school and about four hours later, hopped on a plane to Iraq.

On the way there, I felt scared. What if this would be the last time I saw my family? I knew there was a chance that I wouldn’t make it back, but I prayed and asked God to help me, to not be afraid of suffering.

Early obstacle turns into inspiration

Three days before I left for Iraq, the interpreter for the organization that I was working with, Free Burma Rangers, died. A week before he passed away, an ISIS sniper shot him when he was rescuing a little girl.

It looked like he was going to make it, and we all thought he was going to be fine. His name was Shaheen. He was a Yazidi, a Kurdish religious minority. He died three days before I left. My dad actually ended up going with me to Iraq to go to his mourning ceremony.

I arrived in Kurdistan and we went to Dohuk where Shaheen’s family was staying, and we went to his mourning ceremony. Shaheen’s father talked about how Shaheen not only died for the Yazidis, but for all of Iraq.

He looked at my dad and said, “Just as I allowed my son to fight for Iraq, I think it’s really great that you’re allowing your daughter to do the same thing, and that’s an example for other people.” My dad is very passionate about the people of Iraq.

He offered several times to pay the way for doctors in Springfield to go help. At first, those doctors say they’d love to but then they back off when they realize what they’re getting themselves into. So, I thought, “Maybe if I go, a 21-year-old nursing student from Missouri State, maybe that will inspire other people to do the same.”

Discover more about Free Burma Rangers

The first week and an alarming discovery

We left for Mosul the next day with a group from Free Burma Rangers. On the way there, we stopped through several checkpoints in Erbil, which the Iraqi military has kept really safe. The Peshmerga Army in Kurdistan has done a great job pushing back ISIS. It’s really hard to get from Erbil to Mosul because they want to let people go to help, but they don’t want ISIS to get back into Erbil.

It’s supposed to be about a three-hour trip, but it took probably seven hours to get to Mosul. About 30 minutes outside of Mosul, we looked to the side of the road and there were three ISIS guys on the side of the road, dead, who had been shot. Many of the refugee camps take all the refugees in, but they don’t really know who’s good and bad, so they interview the men and when they find out their story doesn’t line up right, they either take the ISIS guys for trial or they just shoot them.

That’s what I assume happened with the guys on the side of the road. I thought, “Oh, my word. I’m not even to Mosul yet and there’s ISIS dead bodies on the side of the road.”

The first week I was there, we stayed in an abandoned IDP’s home. IDP stands for Internally Displayed Person. The difference between an IDP and a refugee is a refugee is someone that has left their home and gone to another place where it’s safe. IDPs can’t leave their homes, so they just go to a refugee camp.

There’s not a lot of options for them. We stayed in one home where it was hard to see the broken glass on the floors. The rooms were destroyed because ISIS members stayed in that house before we got there. You see little shoes and kids’ toys, pictures, a Quran.

You just wonder, who are these people? Are they still alive? Where are they?

We stayed in that house for about almost a week and we set up a clinic outside. We had basic medical supplies. Antibiotics. Allergy medication.

IDPs who were fleeing their houses would come by, see our car and know Americans were there. We gave them medical care, food and water. It was just hard to see all that these people had gone through and so we stayed there for a week.

Living under ISIS’s shadow

My dad left after four days. We were still at this house and we were still doing the clinic outside of the house and giving the IDPs food, water and medicine. But one day, a man was looking at our house and just this angry expression on his face.

Most of the IDPs were so happy to see us, so there was just something off about this guy. Iraqi Army members lived in the houses next to us, and they saw he was acting suspiciously, too. They asked the IDPs who were hanging out over there, “Hey, do you know this guy?”

As it turns out, he was an ISIS sympathizer, so the Army detained and questioned him. They made him bring them to his house where he was staying. Inside, they found a suicide vest and bombs, He was planning to blow us up.

After that, I realized that I don’t know who’s an ISIS sympathizer. You just assume that people need help, but some of them would leave and go tell ISIS, “There’s Westerners here in Mosul” and give away them our location.

So, right after the Iraqi Army detained that one guy that was planning to blow us up, they made me go inside because another suicide bomber was on the way to our clinic, planning to blow us up.

I heard gunshots outside. It was scary, but I felt OK, because I was like, “OK, these guys know what they’re doing and it’s only a couple ISIS guys versus everyone else, and the Iraqi Army.” When you’re staying in an IDP’s house, as Westerners, we have to leave that house every couple of days because ISIS very quickly finds out our location.

But we stayed in that house just a little bit too long. That night we moved just about a mile away, which felt a little bit safer. We were staying in an IDP’s home, but there was more Iraqi Army, and we were a little bit further from the front line. We set up our clinic outside of the house for a couple days there, and continued to hand out food and water.

Shocking scenes from the front line

The first week that I was in Iraq, the Iraqi Army wasn’t really making a huge push against ISIS at that time. But after we moved to the second house, that’s when they really made an attack against ISIS. I started working at the casualty collection point which was about a mile off the front line. There, I worked with an Iraqi doctor named Major Mohamed and Iraqi medics. They typically spent 10 or 11 days at the casualty collection point, then go home to see their families.

It was amazing to see Major Mohamed’s sacrifice. He didn’t take any time off. Not one day to go home and visit his family. He showed me pictures of his family and how much he loved them, but he just felt like since he was a leader, he needed to stay there and guide the medics in their training and medical work.

I worked there every day for about two weeks, and seeing the death and blood really wears on you. He didn’t have any time off for about four months, which was amazing.

While I was there, I treated refugees and civilians who were fleeing from ISIS, and also Iraqi Army members who were wounded by ISIS. They had gunshot wounds, mortar wounds and burns. I also treated chemical weapon patients. That was one of the hardest things to see.

It was almost like a horror movie, you know?

We had 15 chemical weapon patients come in one day, and they were just pouring sweat. Their mouths were foaming, they were gasping for breath, and their eyes rolled back in their heads. Five of them lived.

There’s not a ton you can do for that at the CCP. We gave them hydro-cortisone and oxygen, and just did everything we could. It’s really hard because you wonder, “What else can I do?” You almost feel helpless. I questioned if this was this too much and too big for me.

“She’s already gone. What do I do?”

One day I was at the casualty collection point and that was a really hard day. They were pushing against ISIS and civilians were fleeing, and I remember a 13-year-old girl came in. She’d been shot in the femoral artery and she was bleeding out. I thought, “She’s already gone. What do I do?” I did compressions on her for about five minutes, and just saw no life. Felt no pulse. I put my stethoscope on her chest and listened. Silence.

She was beautiful. This girl had a dress on. She had earrings in. It was crazy to look at her and think that she had been living under ISIS for about three years. She was so close to making it. She just wanted to live and if she could have just made it to us before she died, she might have been OK. There was nothing we could do. We heard no pulse, so we got a body bag and she left.

Some days it seemed like there was just so much blood on the floors, and we didn’t have enough beds. People laid on the floor, so you’re working on one patient and someone’s dying on the floor, and it’s like you can’t do everything at once. So, we just had to do our best.

Bringing happiness to Mosul

I worked with a smaller non-governmental organization (NGO) called Free Burma Rangers. A former Green Beret started it. He was in the U.S. Army for 10 years and then he went to seminary school because he felt like God was calling him to do something different.

After seminary, he went to help the people in Burma because there’s been a civil war going on there for what seems like forever. Groups there persecute Christians. He helped in Burma, and then when the fight against ISIS started, they asked him, “Hey, can you help us?” He worked in Kurdistan when Kurdistan was fighting ISIS and later worked in Mosul.

I wanted to go somewhere where we could be there to hug the mom who just lost her children or the wife who lost her husband, and mourn with them.

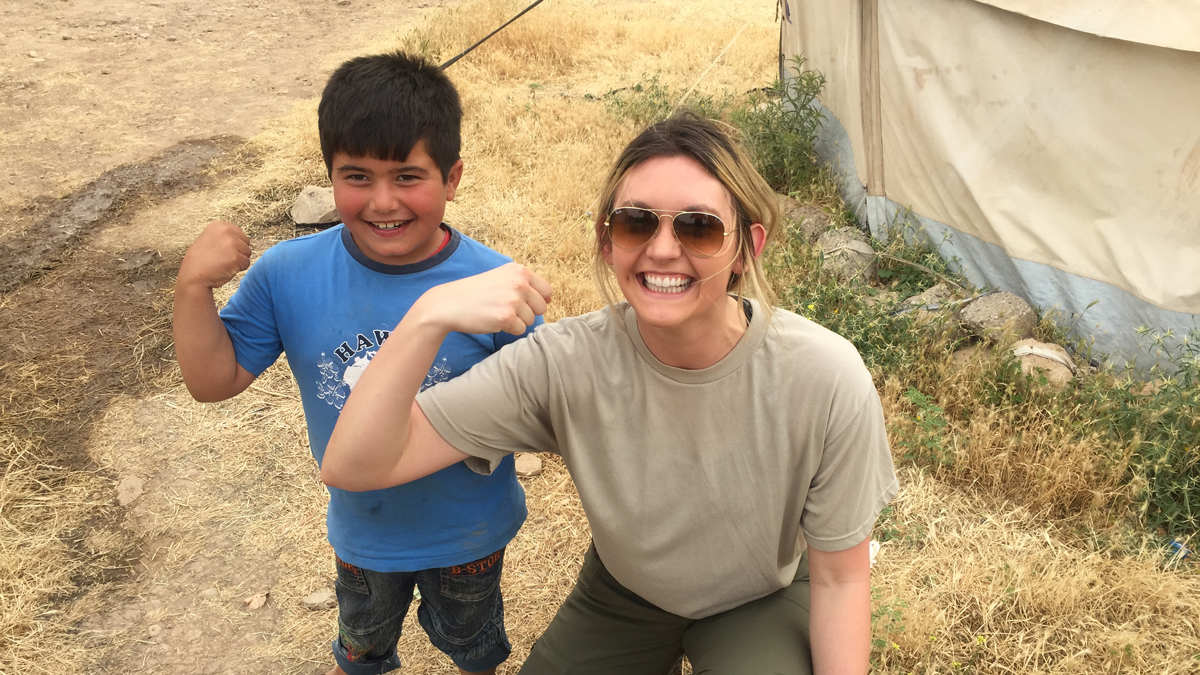

So, that’s the reason I chose to work with Free Burma Rangers. I just tried to just be a happy, joyful person, and bring life to not only the people I was working with, but also the civilians and just everyone I was around. All they had seen was darkness for so long.

We did yoga on the roof. That’s a little dangerous since mortars could hit you. We tried to have routine and work out, do exercise every day. I just tried to bring life and happiness into the CCP because they were just working there day after day, and it becomes really hard when you can just see people dying every single day.

I can’t imagine working there for as long as they did, so I tried to be funny and joyful. We actually had a lot of fun in the casualty collection point when we weren’t treating patients. You think, “Oh, Iraq is dangerous everywhere” but there’s beautiful parts of Iraq, and I even went on a date in Kurdistan.

Why’d I go? Because I love them

Before I went to Iraq, I didn’t have a bad view of Muslims, but you only get the Springfield version of the Muslim culture here. You hear a lot of the bad stuff, but I worked with a Muslim translator. He was working with Christians, so two different religions joined to help people.

This man was the most amazing, kindhearted person who had a lot of the Christ-like character that I strive for. He always encouraged people. He chose to work with Christians, and that was amazing. My view of the Muslim culture is so different now that I’ve been to Iraq.

The civilians there were so happy to see us. Some sympathized with ISIS, but a lot of them asked us, “Why did you come here? Why did you come halfway across the world? You live in America, they’re the best place. Why did you come here?” We went because we love them and we think that’s what God wants us to do. We’re no better. They were just born in a different place.

Because if I was in that situation, I’d want someone to come here and tell me this:

“Listen, I’m here for you. I love you and I’m going to stick with you no matter what happens.”