Volcanoes are mysterious. Many questions remain about how and why they erupt.

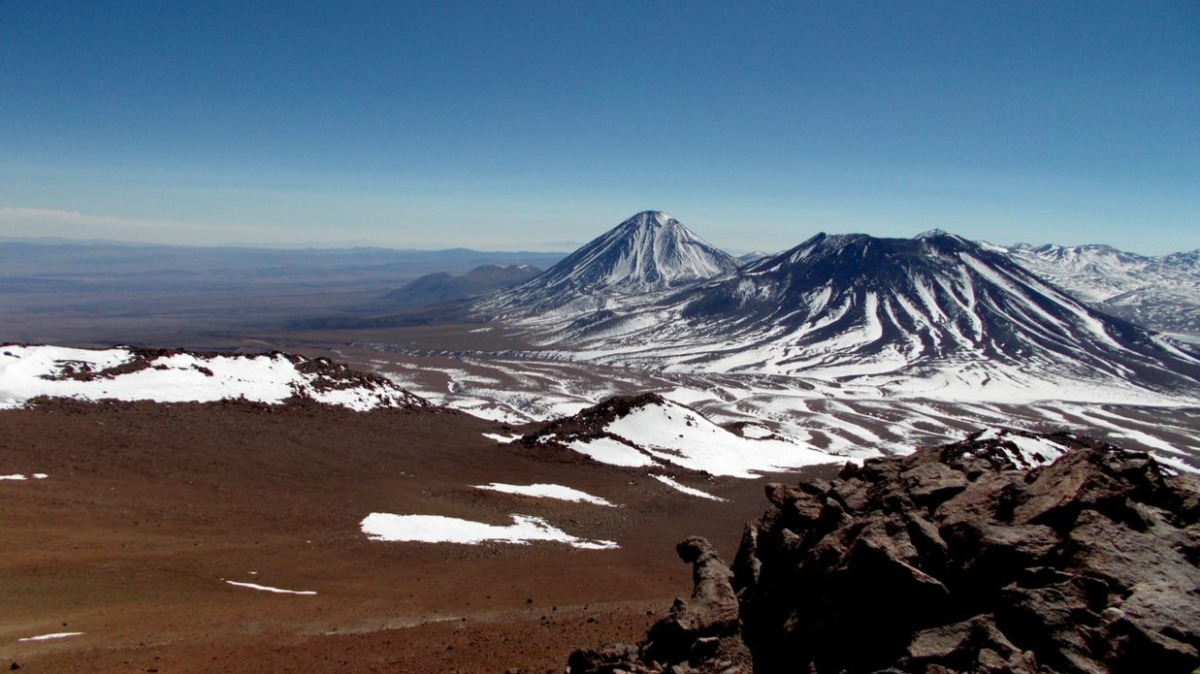

Dr. Gary Michelfelder, associate professor of geology, leads research at five active volcanoes in the Central Andes of Chile and Bolivia that just might provide some answers.

These volcanoes have one important thing in common: a large reservoir of magma, the molten rock material of Earth’s crust. Researchers believe this could be the source of some of the largest eruptions on Earth.

“Our research is the first attempt to connect a large magma reservoir definitively with volcanoes on its surface,” Michelfelder said. “We want to see if each volcano interacts with the reservoir differently.”

His team’s efforts could reveal more about how volcanoes work. This knowledge is key to keeping populations surrounding volcanoes safe.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) recently awarded a $240,000 grant toward Michelfelder’s research.

Making sense of magma

When magma comes out of the Earth’s surface, it becomes what we know as lava.

While magma is not dangerous, lava can be. The degree of danger it poses depends on the style of a volcano’s eruption.

“The style we are studying is very unpredictable,” Michelfelder said. “The volcanoes can erupt violently and affect a large area around them and potentially around the world.”

Michelfelder and other researchers know that magma can feed volcanoes’ eruptions. But they don’t know where magma comes from or how volcanoes accumulate and store it between eruptions.

Since many of the volcanoes they study are in the desert, Michelfelder hopes they can investigate the landscape to see the preserved history of eruptions.

Digging into the science

Michelfelder’s team believes that the volcanoes fed by the magma reservoir could store magma longer.

“This is significant, as the more magma a reservoir stores, the greater the eruption it can feed,” Michelfelder said.

The Central Andes have at least 15 volcanoes the size of Yellowstone National Park and hundreds the size of Mount St. Helens.

The magma reservoir believed to source them all is roughly the geographic size of the states of Missouri, Oklahoma, Iowa and Kansas combined.

Michelfelder’s team questions how much of the reservoir’s magma might erupt at one time.

“If a magma reservoir grows quickly, then more magma is capable of erupting,” Michelfelder said. “If it grows slowly, regardless of how, the volcanoes are less likely to have a large or violent eruption.”

Bringing better safety to the surface

Volcanoes’ eruptions can put a lot of people at risk.

By learning more about how the volcanoes in the Central Andes work, Michelfelder hopes to reduce the danger of volcanic hazards around the world.

“If we can understand these volcanoes, we may be able to apply our findings to similar volcanoes elsewhere,” Michelfelder said. “Populations surrounding them often rely on such understanding.”

The flow of lava or very hot ash and avalanches of debris are common volcanic hazards surrounding populations encounter. Protecting people from these hazards later can start with a better understanding of the past.

“If we can determine the rates of magma accumulation in the past,” Michelfelder said, “we can better understand how volcanoes will behave in the future.”

The tools of discovery

Michelfelder has conducted research in the Central Andes for over a decade now.

But only recent advances in technology have allowed him to seek the answers to how magma reservoirs influence volcanic eruptions there.

“The technological instruments themselves we use have been around for decades. But we’ve learned to apply them in new ways,” Michelfelder said. “This allows us to have more focused questions, which we can then apply to new geographic areas.”

His team’s studies also in part involve unique use of the mineral zircon, which helps them determine the precise ages of rocks.

Unlike other studies that use this mineral to date rocks, they work on very young volcanoes.

“We push the boundaries of what we can do with the mineral,” Michelfelder said. “This work has never been done in the Central Andes.”

About the NSF grant

NSF will distribute the grant over three years.

It will fund the thesis of at least three graduate students and the research experience of two undergraduates.