Living with a Lisp

“No one says, ‘I love having a lisp,'” Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz said.

A lisp is common in preschoolers and often recurs when a child loses teeth. In some cases, speech therapy can treat a lisp, but not always.

Lockenvitz, assistant professor of speech-language pathology, studies the life experiences of those with a persistent lisp.

“Something as minor as a childhood scar, acne or body odor can affect your self-confidence. A lisp can, too,” she said.

She started her career studying how to transcribe and articulate certain sounds. It was a very black and white, quantitative research project.

But reading a personal account of one author with a lisp led her to explore the softer side of research.

“I’m interested in storytelling,” she said, “and the reflections of a life with a lisp.”

Lockenvitz began recruiting subjects to interview. Quickly, she found that identifying subjects to participate was a major hurdle.

Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz creates a mold that will be used to form a SmartPalate.

As she advertised online, many initially responded that “they knew someone who would be perfect for the study,” she said. After more careful consideration, many bowed out. They reported that they couldn’t broach the subject with their friend or family member. It was too sensitive of a subject.

Coping mechanisms

Eventually she gathered a large enough sample size to proceed. Once she began collecting surveys and interviewing subjects, several themes appeared.

Some were predictable: feeling different and lacking confidence in social encounters. But other themes that surfaced surprised Lockenvitz.

Stuttering and lisping affect speech patterns differently, but they both have immense repercussions on communication.

Avoidance appeared as a common coping mechanism for those in her study.

A person with a lisp might avoid words with prominent “s” or “z” sounds. This avoidance interrupts the flow of conversation to reword a response. It not only slows conversation, but it adds to the feelings of isolation and being different.

“I had a participant who talked about only memorizing vocabulary words in his SAT preparation book that did not have s’s in them,” Lockenvitz said. “It blew me away.”

Avoidance had become so ingrained in his life. He automatically skipped over the difficult words – even in a scenario that wouldn’t require him to say them.

Social sensitivity

Lockenvitz also analyzed the responses and identified a lack of social sensitivity toward lisping. Previous studies on stuttering showed that people recognized it was socially unacceptable to tease someone for this speech disorder. Those with a lisp still felt victimized.

Student Allie Savich uses a SmartPalate in the Speech-Language and Hearing Clinic.

“Making fun of speech problems is apparently acceptable in our current state of society,” Lockenvitz said. “It’s sad.”

One speech language pathologist who participated in the study had a lisp herself. In addition to difficulty with the sounds, she had a visual lisp. Her tongue thrusted forward, protruding between her teeth.

She shared how her colleagues talked about her lisp behind her back. They put her on the spot, at times making her feel shame. But the worst critic was her daughter, the up-and-coming comedian.

“It was part of her bit,” Lockenvitz said, “the speech pathologist with a lisp. It really hurt her mother.”

One of the participants said, through her tears, ‘I want to tell this story. I want to contribute to your research because it’s so important. It really has affected me emotionally.’

Testing technology

Lockenvitz is collaborating with Dr. Alana Kozlowski, associate professor of communication sciences and disorders, on a project to retrain lisping tongues using biofeedback.

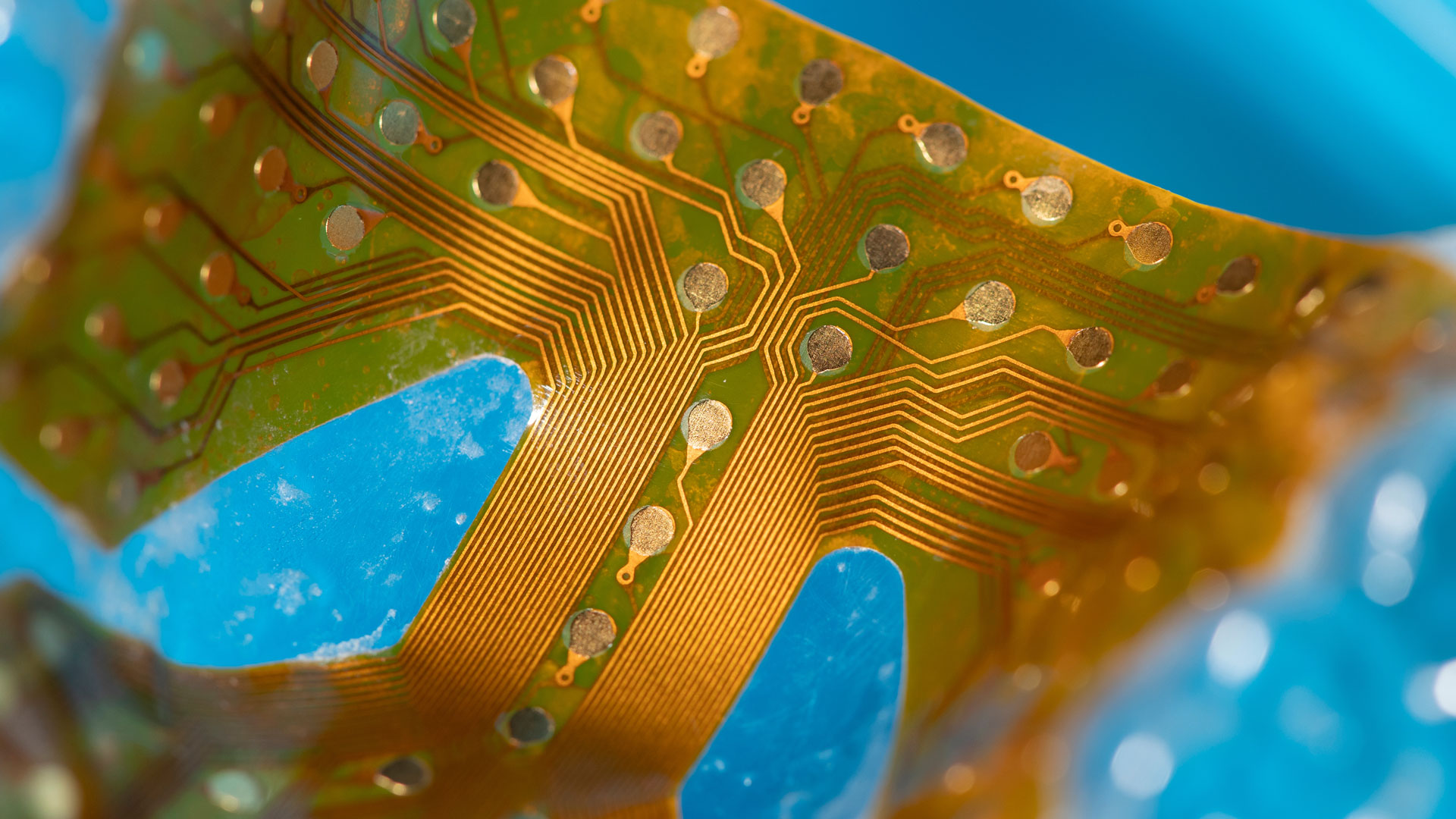

A SmartPalate used as a feedback device in Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz’s research on lisping.

Graduate students in the Speech-Language and Hearing Clinic take molds of the mouths of adults who have a persistent lisp to design a palate. The palate, with sensors inlaid throughout, can be placed in the roof of the mouth. Once connected with the software, it can show the contact points between the tongue and palate.

“The clients have a visual to show them where the tongue should be to make the sound correctly,” Lockenvitz said.

While the technology has been used in the field for many years, Lockenvitz and Kozlowski are using it in an innovative way. They are applying the principles of motor learning along with this technology.

When motor learning is used in an intervention strategy, clinicians offer feedback to work toward independence and consistent accuracy.

The treatment or interventions for persistent lisping requires more research, she added, but the possibilities excite her.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams