Military health: Detecting and controlling disease

He got the job of an Environmental Science and Engineering Officer. A broad role, it covered areas such as industrial hygiene, environmental health, vector control and food service.

“After doing all these things, I realized I’m a public health person,” said Thompson, associate professor of public health at Missouri State University. “The Army is the reason I got into human health. It’s been quite the experience and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

The military and the spread of diseases

Thompson has completed several research projects related to the military. One of them explored the movement of military personnel and its impact on global health. It resulted in a published book chapter.

For the study, Thompson looked at how military operations – both past and more recent – have contributed to the spread of diseases. These include vector borne, infectious and emerging diseases worldwide.

“The Army Reserves became a secondary career and compliments what I do at Missouri State. Doing the Army stuff keeps me engaged in the game and my knowledge base current on public health issues, and I can pass that on to students.”

For example, the flu pandemic that swept the globe during World War I was due in large part to troops moving around.

“When you congregate people, ship them some place and mix them with others, you can get large-scale outbreaks,” Thompson said.

In more modern times, large-scale outbreaks are rare. But Thompson notes that military operations have:

- Expanded the geographic distribution of many diseases. These include those thought to have been eradicated in a region.

- Led to the emergence of novel diseases.

Examples include cholera, malaria, pertussis, and leishmaniasis, which is a parasite disease spread by sandflies.

“We see things like bacterial infections you don’t often see in western hospitals,” Thompson said. “Because of blast injuries, shootings, and exposure to bacteria in combat areas, those have entered hospital settings. Some of them are antibiotic resistant.”

As military forces continue to move about for combat and peacekeeping roles, they spread diseases. Reducing the risk is key.

“These militaries can improve surveillance,” Thompson said. “It involves partnering with local governments and officials to improve their capacity and capabilities.”

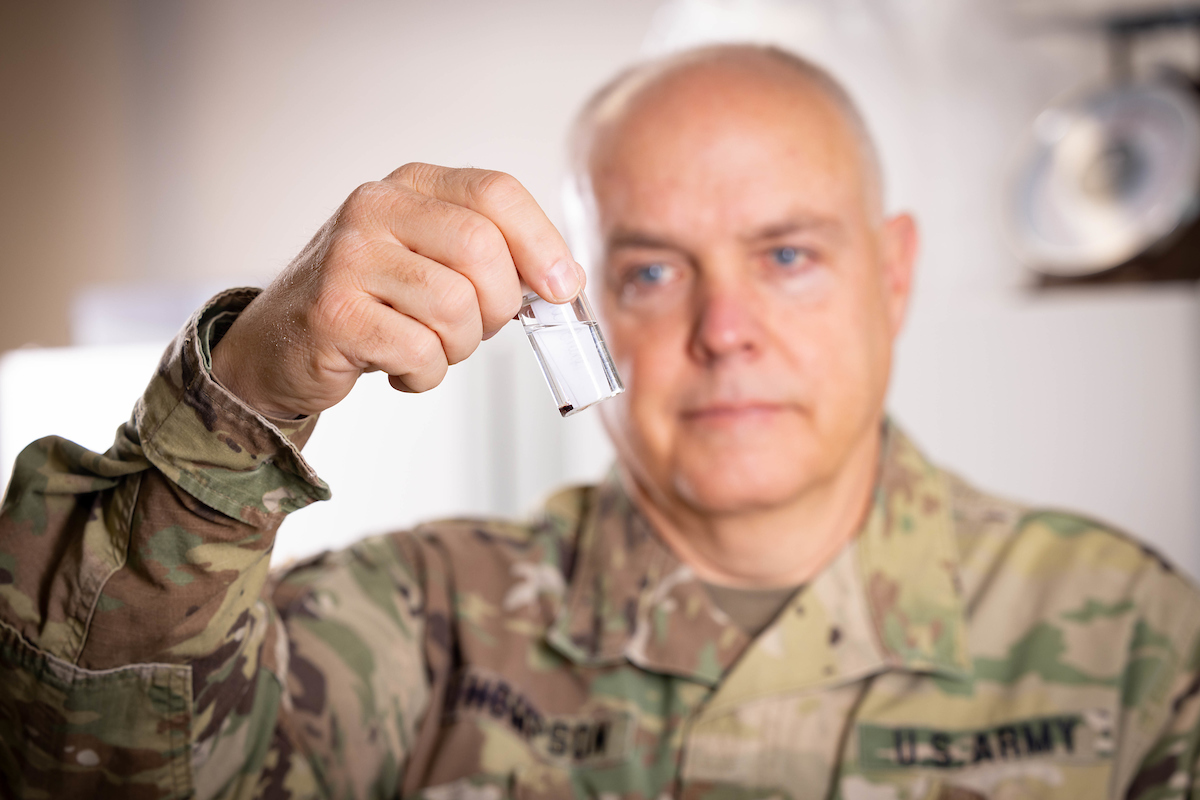

Dr. Kip Thompson values data to help predict and track possible outbreaks among military and civilian populations.

Studying data to predict an outbreak

When it comes to tracking and predicting diseases, data offers valuable clues.

Thompson points to the reports from each country’s local disease tracking system. During his deployments to Honduras in 2016-17 and 2018-19, Thompson received such reports weekly from the Honduras Ministry of Health.

“Public health in the U.S. tends to chase its tail. We’re not proactive, we’re reactive. I don’t know when we changed. We used to be more proactive and it’s probably a funding issue.”

He would track diseases of concern in his area and noticed a pattern. Each time he saw a gastrointestinal (GI) outbreak in the local population, an outbreak among service members soon followed.

“I tried to figure out, ‘was there a predictive component to that?’” Thompson said. “It turns out there was.”

As part of the medical unit, he was able to warn military personnel of the increased GI risk. He also shared reminders for preventive actions.

“You can’t always stop the spread of an illness, but we were able to at least reduce it,” Thompson said.

He’s completing a paper about the research for Military Medicine.

Public health expert Dr. Kip Thompson looks at how military operations – both past and more recent – have contributed to the spread of diseases.

Controlling an outbreak with technology

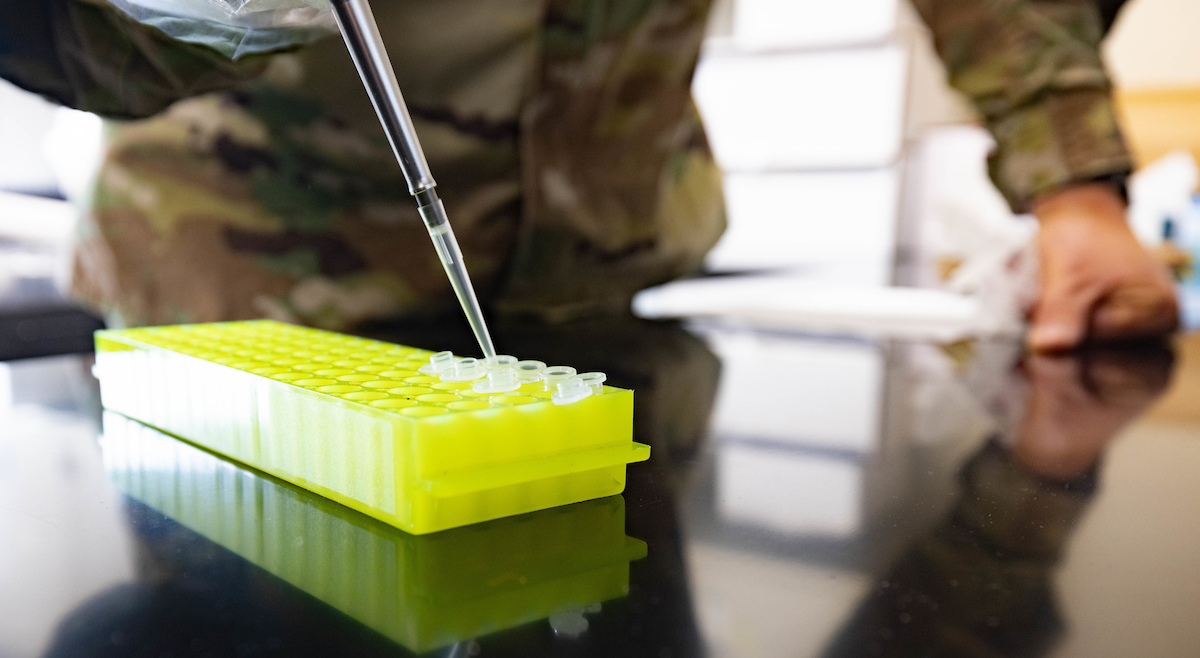

Thompson has also delved into using technology to speed up the identification of infectious agents.

Service members who live in close quarters on base are at risk for rapid outbreaks of diseases like GI. To control them, quick detection of the cause is critical.

When Thompson was in Kuwait, his Preventive Medicine unit had polymerase chain reaction (PCR) capabilities. PCR enabled RNA or DNA sequencing to detect the pathogen of an outbreak within hours.

Using the system, he and his team were able to quickly identify a GI outbreak caused by norovirus.

“Because of that, we were also able to reduce the disease burden,” Thompson said. “The incidence of disease was down 10 fold compared to locations with the same outbreak but without the system we had.”

He co-wrote an article about this study for the U.S. Army Medical Department Journal.

According to public health expert Dr. David Claborn, Thompson’s military health care expertise is crucial to the overall study of public health.

“The military can affect American citizens and international populations alike,” said Claborn, director of Missouri State’s Master of Public Health program. “The study of military health care is as applicable to the civilian population as it is to the military.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Kevin White