Search results for "Goerndt"

From the ground up: Nutrition starts with soil

Soils can be enriched with nutrients to grow strong, healthy grass for livestock to consume. Many of the nutrients transfer to your plate when you eat meat, or the fruits, vegetables and grains harvested.

Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, associate professor in the Darr College of Agriculture at Missouri State University, has conducted many research projects focused on the chemistry and nutrition in soil.

“I’ve always loved plants. My father worked for John Deere, so agriculture was part of our family.”

In recent years, the agriculture community has emphasized the importance of testing soil composition then improving the chemistry. Farmers may do this by adding nutrients to the soil or to the solution that waters the field.

“Not only can you grow more food, but it’ll be healthier. And in turn, you might not have to add supplements to your cattle’s food,” Bledsoe, a plant physiologist, said. “By investing a little bit more in your soil, you can get a better benefit.”

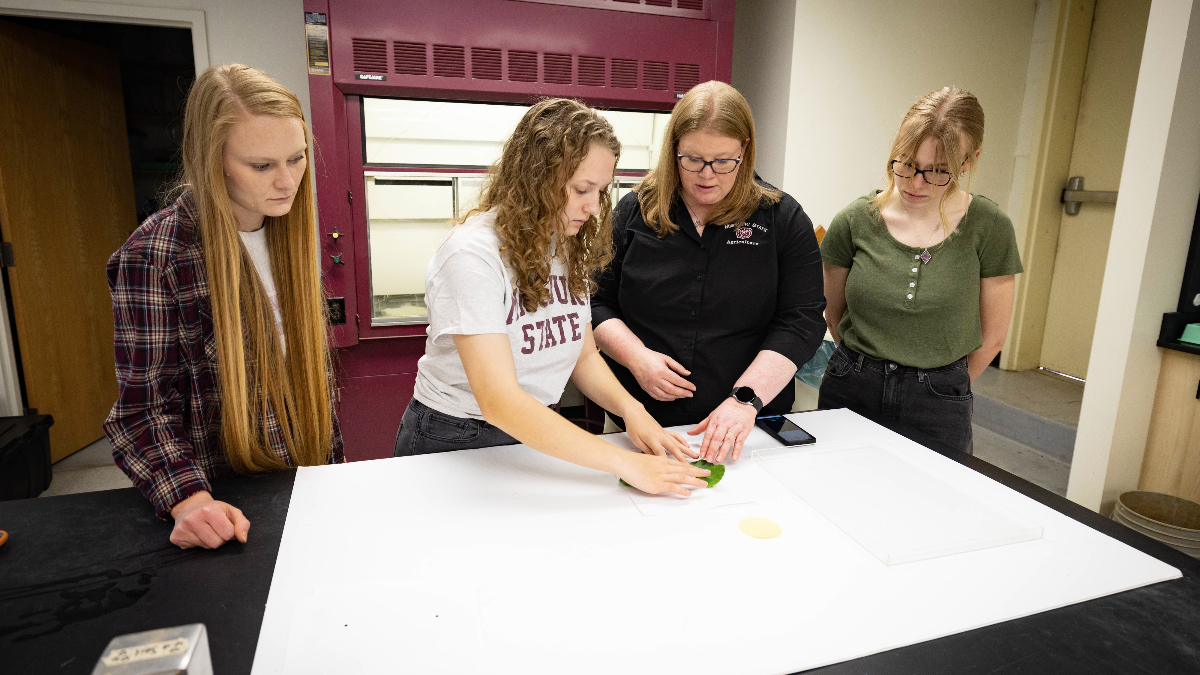

Horticulture student Gwenyth McClain works under Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, learning to test soils and plant tissue.

In Karls Hall at MSU, Bledsoe teaches her students to test soils and plant tissue. These tests can show how soils need to be adapted to meet the goals for the crop.

Bledsoe integrates research into her teaching, and she values building projects around her students’ interests and questions.

She relates this back to her own experience as a graduate student studying under Provost Dr. Frank Einhellig. He inspired her to dig deeper into research and ultimately pursue her doctoral degree.

A finding about phosphorus

Grass tetany, a fatal disorder in cattle, is related to low magnesium in a cow’s diet.

In previous work, Bledsoe and colleagues found soil must have adequate phosphorus levels for magnesium to reach the leaves of tall fescue.

“The Ozarks has acidic soils, which means our phosphorus levels are low,” she explained. “Grass tetany is more of an issue in our tall fescue pastures than in many other places.”

This led to another study, and another publication in 2019. This time, the team focused on other common crops, such as winter wheat, oats and cereal rye.

Students are an integral part of Dr. Melissa Bledsoe’s lab.

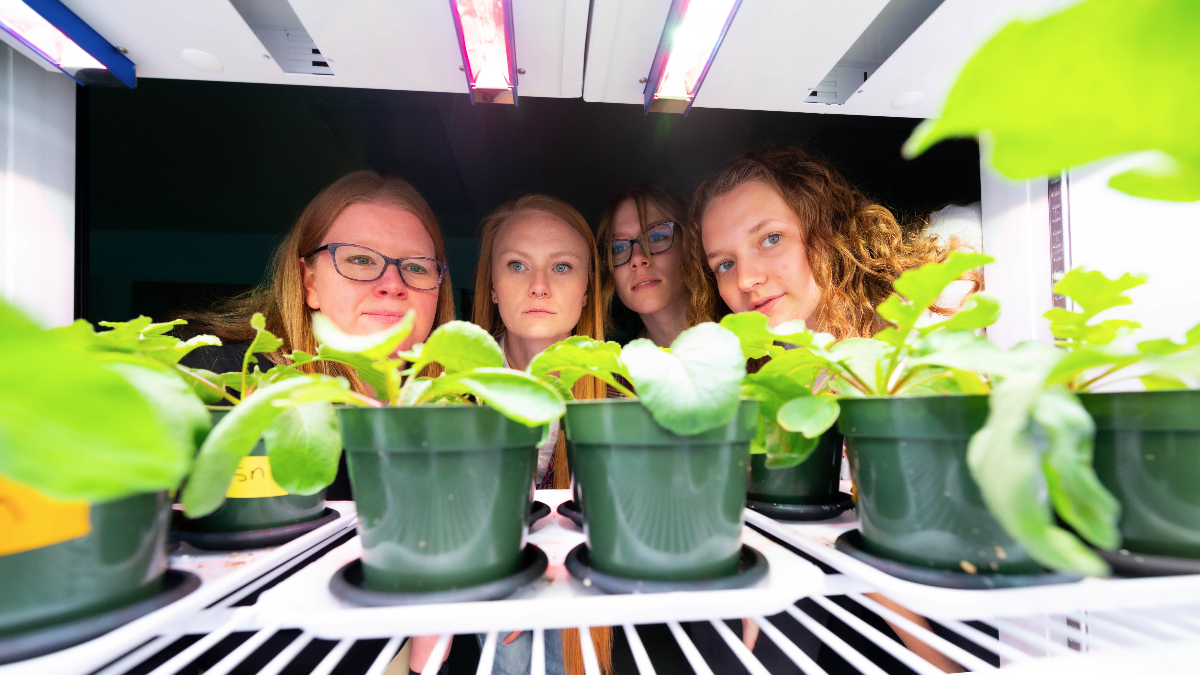

Starting small, her students set up the experiment in hydroponics. This allowed them “to manipulate the mineral nutrition very specifically to see how the plant responds.”

Then, they expanded the study to the field, hoping to zero in on how adding phosphorus to the soil affected the magnesium in the winter plants.

“Our abilities are flexible. So when a student says, ‘I’m really interested in growing vegetables,’ we think about a way we can solve a question about that.”

While winter wheat was responsive to the addition, the other winter annuals were not.

Though the study didn’t indicate that there were benefits for the other winter annuals, Bledsoe spins it positively.

“Even finding that some plants don’t respond is still an answer,” she said, noting that it’s a learning opportunity for students. “It gives them a reason to continue testing the techniques with other variables, too.”

Students Mary Books, Sarah Overbeck and Gwenyth McClain work to gain greater understanding of how to improve crop production.

Establishing a silvopasture

At Journagan Ranch, a Missouri State property in Mountain Grove, Missouri, Bledsoe has worked alongside Drs. Michael Goerndt, William McClain and Toby Dogwiler on a major U.S. Department of Agriculture grant project since 2018.

Here they have established a silvopasture to study.

In simpler terms, a silvopasture means you’re optimizing land to grow trees and grass together in a way that benefits both to get higher yields.

“We want to grow forages for grazing cattle in this area. If we can grow forages under trees, we can get a second crop with trees,” Bledsoe said. “Meanwhile, we’re providing shade and cooler temperatures for the cattle.”

It takes a long time to establish these plots before they are producing at full capacity, Bledsoe stressed. All along the way, the team monitors and measures tree health, soil nutrition and forage growth for baseline data.

“We can map the area but also monitor how those trees are growing, how the grasses are growing and see what stresses they’re under. Ultimately, over time, we can also monitor production and growth with drone flights, and we’ll have on the ground measurements to compare that to.”

In Dr. Melissa Bledsoe’s lab, she uses growth chambers to ensure stability of variables.

As the roots deepen and the trees thrust upward, the team will continue to track at periodic tipping points throughout the year:

- At the end of winter, before the plants bud and leaf again.

- After stress from a drought.

- Before the leaves wither and fall.

Learn more about the silvopasture project

“We want to prove how a silvopasture system can benefit a producer and how these systems might help the trees and forages be healthier,” she said.

Helping farmers

In her role, Bledsoe mentors students in agronomy and horticulture. Her interest in soil health and nutrition serves as a springboard for a broad range of students to jump into research, she noted.

“We have students that range from horticulture to agronomy and we want to have all those students be interested in research.”

Her projects dig in many different directions – garlic, microgreens, and fescue to name a few. At the root of each, she sees a commonality.

“We’re trying to help local producers have healthier soils and healthier forage production, so they can have fewer issues with their cattle,” Bledsoe said. “For me, I love working on real world problems that can alleviate the pressure on these producers.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Further reading

Seeing the forest and the trees

This reduces the amount of sunlight hitting the ground.

If left in such a condition for too long without disturbance, important tree species cannot regenerate. Invasive or shade tolerant species creep in and animals leave the area, in search of better food.

Or maybe the trees simply age, produce less fruit and continue to weaken. These scenarios drive the forestry field and forest management decisions.

“Forest management is intentional, planned disturbance,” said Dr. Michael Goerndt, assistant professor in the Darr College of Agriculture at Missouri State University. “When forestland is managed for multiple objectives, we can effectively grow better trees and companion crops and maintain diverse habitats.”

He explains that it comes down to planning for ecological succession. This entails designing the future of the forest and predicting what it will be under specific conditions.

With a father and brother both in forestry, Goerndt learned about forestry since he was a young boy. He’s a self-proclaimed “math goon.” This led him to specialize in forest biometrics focusing on measurements and data analysis for forests.

“Everyone should have a better understanding of statistics. We use it constantly. Most people are using it daily and don’t even think about it. They talk about how many miles per gallon their car gets. That’s stats.” – Dr. William McClain

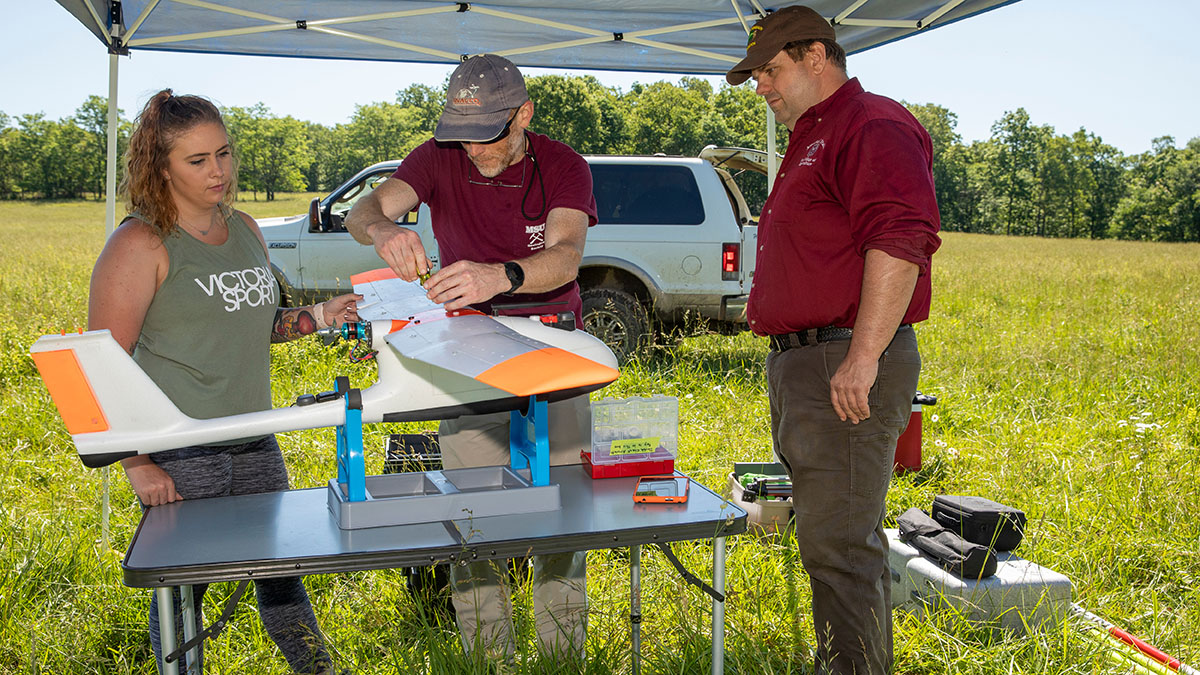

This now incorporates the latest technology, such as remote sensing, satellites, drones and spectral imagery. Using these tools, he collects data from forest landscapes with help from geospatial science experts, like Dr. Toby Dogwiler.

A drone hovering over the tree canopy may reveal beautiful aerial imagery of the forest. But it also puts into focus the challenges that lay beneath.

“Technology gives us the opportunity to get data for very large areas more efficiently than we ever could with boots on the ground,” Goerndt said. “That’s where the science of forestry is headed. As our ecological challenges mount, we must look to the trees as a critical component for addressing landscape degradation, pollution, climate change and alternative fuels.”

Left to right: Austin Livingston, Stewart McCollum, Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, Dr. Michael Goerndt, Dr. Toby Dogwiler and Bailey Wolf at Missouri State’s Journagan Ranch.

Productivity of land

Goerndt has grown the curriculum for forestry at Missouri State, and published more than 15 articles in the last 10 years. Many of these publications have come from his research assessing potential biomass availability in forestlands.

Now he’s working on a collaborative study, funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture with Dogwiler, Dr. William McClain, Dr. Melissa Bledsoe and two graduate students. The study will showcase exactly how much more productive an area of land can be if managed for multiple crops and products.

“I’m proud of the fact that we made it work that two students are going to get their degrees out of the project.” – Dr.William McClain

In the initial phase, Goerndt and his collaborators identified three study sites at Missouri State’s Journagan Ranch.

“We’re creating the capacity here to do years and years of long-term research,” he said.

Dr. Michael Goerndt talks with graduate student Stewart McCollum.

There’s a control site of about five acres comprised of tall fescue. A second five-acre site of natural mixed hardwood forest has been thinned down to simulate a savannah. The third plot, about five acres, will be a site of a walnut plantation for research and future collaboration with Hammons Black Walnuts.

Using these sites, the team will compare cool-season and warm-season forage growth. They will investigate the synergistic relationships between trees and forage. They will also assess the economic and ecological benefits of intentionally converting either fields or forests into silvopasture land, which means managing land to integrate trees with livestock grazing.

“The silvopasture project is right for in the Ozarks because we’ve got a vast amount of two things: trees and cows.” – Dr. Michael Goerndt

On all of his projects, though, Goerndt wants to bring it down to earth and show the practical application.

“In a nutshell, I always want the takeaway to answer one question: ‘How can the real stakeholders apply this in their lives?’” Goerndt said.

Dr. Toby Dogwiler (center) and graduate student Bailey Wolf (left) prepare a mapping drone with Dr. Michael Goerndt.

Growing biodiversity

Through a sustainability lens, Goerndt’s work is very valuable. In addition to identifying sites with the greatest potential for renewable energy sources, he advocates for greater biodiversity.

Rather than continuously simplifying the landscape and allowing one species to dominate a forest, his research brings to light how different species can coexist in a mutually beneficial relationship.

“Foresters know in most cases we are never going to see the full fruits of our labors within our lifetime. The rotation is too long.” – Dr. Michael Goerndt

Biodiversity also builds in safeguards for the agriculture industry.

“If you build a plantation with one cultivar of a crop, you open yourself up to potential devastation,” Goerndt said. “What happens if a fungal disease comes along and wipes out that particular variety? You’re done.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle