Iroquois culture

20th century

Corn husks and hemp fiber, L. 27 cm x W. 7 cm x H. 30 cm

Mace collection #TM176

Iroquois culture

20th century

Corn husks and cotton twine, L. 31 cm x W. 13 cm x H. 39 cm

Mace collection #TM175

The Iroquois cornhusk mask, also known as the Husk Face mask or Bushy Head mask, represents a mythological, human-like people who grow enormous quantities of crops in their supernatural valley on the other side of the world, where the seasons are reversed. The Husk Face people taught the Iroquois how to cultivate crops and to live a thriving sedentary life, and the Iroquois therefore make these masks to honor and to thank the Husk Face people during the Iroquois Midwinter Festival dances; during this dance, the Iroquois also ask for help in ensuring a rich crop yield for the ensuing year. When they are not being worn in dances, the Husk Face masks are carefully stored away, so as not to instigate any further interactions with the spirits.

While the selling of Iroquois ritual objects can be controversial because of the uncontrolled power that the objects are believed to embody, Iroquois artists commonly make authentic, traditional versions of cornhusk masks for the tourist trade. However, as with the two masks in this exhibit, these cornhusk masks are not ritual objects, for they are not given a ritual blessing, and they have not been used in Iroquois rituals.

By Bill Bouchard

Tsimshian culture

20th century

Cedar wood, paint, and horsehair, L. 30 cm x W. 17 cm x H 35 cm

Mace collection #TM027

Among the cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast, masks are functional objects that are used in traditional theatrical performances and in dances, and they may portray spirits, ancestors, religious characters, or secular characters. Traditional masks are also symbols of prestige that are made for and exchanged by community leaders at potlatches, which are large communal gatherings for the sharing of wealth. In recent years, Pacific Northwest Coast artists have also carved and painted masks for the tourist trade that portray typical characters, as well as making their own new and creative interpretations of traditional forms.

This mask was carved from a thick piece of cedar wood, one of the most highly favored materials of Pacific Northwest Coast carvers. The red-painted nostrils and the drooping, teardrop-shaped eyes suggest that this mask was made in the typical style of the Tsimshian culture, and the signature confirms that the artist was Bill Bouchard. However, not only is this mask very heavy, but it has only a hanging wire, and no holes in the eyes or mouth areas. This work was therefore most likely made as a sculpture for display rather than to be a functional mask.

Txukahamei culture

20th century

Feathers and palm fiber, L. 12 cm x W. 7 cm x H. 33 cm

Zinn collection #2014.6

The Txukuhamei are one of many Amazonian subcultures of central Brazil that make and use beautifully constructed feather headdresses. The Men’s Feathered Headdress is typically worn for important traditional rites and ceremonies. This headdress is authentically made from bright feathers, but in a miniature form and with mostly short feathers, while full-size Txukahamei headdresses are large and surround the head in upright feathers. This headdress was therefore likely produced for the tourist trade.

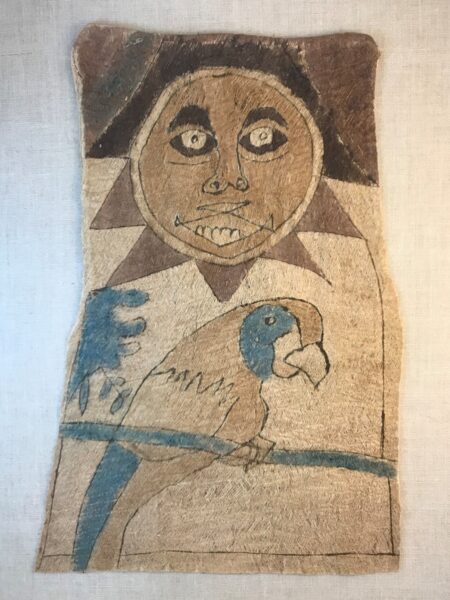

Tikuna culture

Early 21st century

Wood, acrylic pompoms, feathers, and pigment, L. 6 cm x W. 1 cm x H. 9.5 cm

BFPC collection #2003.21

This Tukuna mask consists of a thin, screen-like bark cloth hood that has been painted on the front side. Rather than being woven, the tururi cloth used for these masks is made from the bark of fig trees that has been beaten into a thin, screen-like layer. Once finished, this cloth may be used as the basis for paintings and to make hood masks that are transparent enough for the wearer to see through. Masks made from tururi may be hoods, like this mask, or they may be full-body masks, and they usually have an additional carved wooden face mask on the front; these masks are typically used in dances during coming-of-age rituals. The masks are also commonly embellished with paintings of animals or anthropomorphic figures, which represent bad spirits that should be avoided after the rituals.

This tururi mask takes the traditional form of a screen-cloth hood and is painted with a human-like face and a blue macaw bird. Because the cloth hood does not include a wooden mask, however, it was likely either made to be sold, or it was purchased before it was equipped to be used in ritual.

Navajo/Diné culture

Early 21st century

Wood, feathers, and pigment, L. 7 cm x W. 2 mm x H. 7 cm

BFPC collection #2003.21

The Hopi culture’s Sun Kachina, also known as Tawa, represents the growth and warmth of the sun and its importance in growing crops. The red, gold, and turquoise colors on the mask of this figure represent the sequence of the sun rising, shining, and setting, and the mask is surrounded in feathers to represent the sun’s rays. While the making and selling of traditional Hopi kachina figures and kachina masks in the tourist trade is highly controversial, this figure and its mask is not a Hopi figure, but a portrayal of a Hopi dancer that was produced by a Navajo/Diné artist. The Navajo do not make these figures for ritual purposes, but only as representations of Pueblo culture.

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu