Here is the CODERS Directory for 2023! Find names, photos, emails, and phone numbers of CODERS administration and all of the project participants. Directory Link … [Read more...] about CODERS Directory for 2023

Congratulations on your selection to participate in the CODERS Summer Launch Experience. Tammi, Razib, Andrew, Diana, Judith, and I are excited to see you Monday-Thursday, June 5-8 on the campus of Missouri State University in Cheek 151. This is a change from four to five days. We hope you are okay with this! We will meet from 8:30-4:30. Coffee, conversation, and supply pick-up … [Read more...] about Welcome 2023 CODERS Colleagues

Spring Reflection Reminder for March 1 ★ Teach & complete at least 1 lesson and complete a reflection. For the lesson, choose from the following lesson plan options: Careers Writing and reflecting with the students on their learning using research-based Writing Strategies Computational Thinking Block Coding Cutebot … [Read more...] about Lesson Reflections are due March 1

Coding Olympiad or Student-Teacher Showcase Please bring a team of 4-5 students. A team should consist of fourth through sixth graders OR a team of seventh and/or eighth graders. A school team will be presented a problem to solve related to coding. Points will be determined and awards presented at the end of the day. If you would like to participate in planning, please … [Read more...] about Coding Olympiad on February 27

Thanks for your feedback on the last newsletter! Here is the next one with new information, reminders, and lots of opportunities. Feel free to send any feedback. I really appreciate it. This will also be posted on the blog each week in case you need to find it. … [Read more...] about CODERS Update, Issue 2

Tell you and your students CODERS story. Tell a Pixar Story. Try out this form and share a draft of your story. Use this link with your students as well. Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, [the students, the teacher, whoever the story is about]. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___. After you write your story, take a few … [Read more...] about Tell your “Pixar” Story

All CODERS current and past participants are invited to view and share stories through our newsletter. Please take a moment to read about upcoming opportunities. View the CODERS Newsletter. … [Read more...] about CODERS Newsletter is Out!

The first lesson(s) should be focused on: STEAM or advanced topics (robot dog or drone) Lesson Reflection Talk to Dr. Iqbal for any questions! … [Read more...] about Fourth Lesson Reflection Due on November 30th

PSU Ballroom 8:30-4 … [Read more...] about ReGroup Date Reminder: November 7th

The second lesson should be focused on either: Microbit or Cutebot Lesson Reflection Please try and complete by October 30th! Talk to Dr. Iqbal for any questions! … [Read more...] about Third Lesson Reflection Due on October 30th

Here are the resources that Jennifer Jackson put together for her Makecode Classroom. Set up your Microbit Classroom Microbit Website Microbit PowerPoint Microbit Scavenger Hunt … [Read more...] about Resources to set up your Makecode Classroom

PSU ballroom 8:30-4 … [Read more...] about ReGroup Date Reminder: October 17th

XGO Robot Dog Kit is an AI dog micro robot with 12 DOFs (Degree Of Freedom: facilitates bionic movement) designed for artificial intelligence education for teenagers. It supports Omni-movement and is able to perform as a real pet dog. In this session, Dr. Iqbal introduces the participants to the XGO Robot Dog and its components. The participants also learn to teach the Robot … [Read more...] about XGO Robot Dog

The first lesson(s) should be focused on either: Career Connections and Computational Thinking https://blogs.missouristate.edu/cwccc/2023/06/06/careers-in-cs-and-stem-representation-matters/ https://blogs.missouristate.edu/cwccc/2023/06/05/introduction-to-computational-thinking/ Here's who to talk to for questions: Contact Dr. Franklin … [Read more...] about First Lesson Reflection Due on September 30

We will be in the Plaster Student Union Ballroom from 8:30-4:00 pm. Please bring your laptops/chromebooks with power sources. We look forward to seeing you all soon! … [Read more...] about ReGroup Date Reminder: September 21

The window for completing the student surveys is ..... August 29-September 15! Link … [Read more...] about Complete the Student Surveys

The CoDrone Mini is a tiny and zippy mini drone that can be programmed with blocks using Blockly or with Python. It uses radio frequency to connect the remote and drone, so the range and connection is stronger. Embark on a flying journey with Dr. Iqbal, where he introduces you to CoDrone Mini and how to use Blockly to program the drone and develop computational thinking. The … [Read more...] about CoDrone Mini

Get to know the arts standards and how to apply them in the classroom, and how to add music to your coding lessons. Dr. Homburg walks you through all the important steps of integrating art into STEM projects. Link to Presentation … [Read more...] about STEAM Up Your Lessons: Integrating Art in Coding

DJI Drone CoDrone Robot Dog Smart Home Kit I found these club packs (as of now, it is showing 12 available) on Amazon. Each of these packs has 10 microbits and the price of the pack is showing $285. BBC MICRO:BIT Micro:bit v2 Go Club 10-Pack - Batteries and USB Cables Included https://a.co/d/bPvjYHL Cutebot (ASIN B081ZSCZTV) Vilros BBC Micro/Bit v@ Basic … [Read more...] about CODERS Kit Ordering Information Year 1-3

To be a part of an Institutional Review Board-approved study, researchers have to gain consent from participants. You gave your consent during the Launch. When school starts, we will need you to send home the Passive Consent Form home to students. You will need to read this form aloud to students and explain the cool things you will be doing. There are no real risks that we … [Read more...] about Permission for Students to Participate in the Survey

A smart home is a home equipped with lighting, heating, and electronic devices that can be controlled by a computer. Sensors and actuators are a very integral part of smart home. In this session, Dr. Iqbal introduces the participants to a basic smart home kit and teaches about light sensor, noise sensor and moisture sensor. The participants learn to build a sound-activated … [Read more...] about Smart Home Kit

Below are links to the teacher-tested and approved websites mentioned during the CODERS Launch. Youtube Tutorials for Scratch CS First Flappy Bird Using Scratch Scratch Wiki Getting Unstuck Occupational Outlook Handbook … [Read more...] about Teacher Tested Online Resources

Micro:bit is a small programmable pocket-size computer designed for educational purposes for students. With a built-in LED display, buttons, and sensors, this is the perfect tool for developing computational thinking and learning to design and program. In this session, Dr. Iqbal introduces 'Makecode for Micro:bit' and guides the participants to understand conditions, loops, … [Read more...] about Introduction to Micro:bit

Micro:bit cutebot is a small programmable Bot designed for educational purposes for teaching programming. Go on the wonderful learning session with Dr. Iqbal where he covers hands-on Cutebots activities to teach programming, logic, and computational thinking. Teach your cutebot to stop its motion when an obstacle is in its way. Then build on the radio lessons from the Micro:bit … [Read more...] about Cutebots

Freewriting.pptx is non-stop writing. can move from topic to topic. is writing more than you think you can. is not censored; that means don’t worrying about spelling, grammar, and mechanics. is not worrying about how good the writing is. is keeping your pen on the paper and writing even if you do not know what to say. is writing that is not judged … [Read more...] about Freewriting is . . .

The Missouri Learning Standards define the knowledge and skills students need in each grade level and course for success in college, other post-secondary training and careers." These standards provide insurance that your students learn basic and higher-order skills, like critical thinking and problem-solving. The standards give real-world expectations that allow reflection of … [Read more...] about Missouri Computer Science Standards K-12

Name:____________________________Date:______________Block:___________ Ms. Franklin English IV Revision occurs after you have a complete piece, although revisions occurs at all stages. Match what you have already written with what you now wish to say. Create out of the two a new piece that suits their present purpose Revision never stops The First … [Read more...] about Bones, Muscles & Skin: Purpose and Revision in All Kinds of Writing

The IF/THEN® Collection is the largest free resource of its kind dedicated to increasing access to authentic and relatable images of real women in STEM. The Educator Hub helps you align standards and choose videos for your classroom. Show two videos as week as a bellringer or an exit pass for six weeks. Here in this digital library, you will find thousands of photos, videos … [Read more...] about Careers in CS and STEM: Representation Matters

https://blogs.missouristate.edu/discounts/archives/2780 … [Read more...] about Silver Dollar City Teacher Appreciation Days June 4-30

Scratch is the world’s largest coding community for children and a coding language with a simple visual interface that allows young people to create digital stories, games, and animations. Scratch promotes computational thinking and problem-solving skills; creative teaching and learning; self-expression and collaboration; and equity in computing. The concepts of block … [Read more...] about Introduction to Scratch

Computational thinking is the step that comes before programming. It’s the process of breaking down a problem into simple enough steps that even a computer would understand. Dr. Iqbal explains the analogy between design and computer programming. Have a journey with him where he explains binaries, bits, coding, and many more things related to computers and teaches how to think … [Read more...] about Introduction to Computational Thinking

Here are writing strategies that are evidence-based. We hope that you integrate some of these writing strategies in your lessons. Write to Learn Strategies Daily writing, from freewriting to KWLS to creative forms like Haiku, is a thinking tool for learning in all disciplines. Below is a list of research-based writing strategies that we would like you to try writing to learn … [Read more...] about Writing to Learn

After completing a CODERS lesson, you will reflect on those lessons. We collected reflections last year. Some of you may remember Dr. Davis asking for those. Take a moment to review the lesson reflections. Click through and view the reflections for each of the lessons/concepts. This link will be available through June 16. If you would like access after that, please email Keri … [Read more...] about Lesson Reflections: What Stories Do They Tell?

Interesting article on the increasing demand for degrees in Computer Science. While UC-Berkeley has over 2,000, Missouri State University has nearly 300. Talk with Dr. Iqbal for any questions. Demand for computer science classes has overwhelmed many US campuses in recent years, with growth in student numbers not matched by similar expansions in faculty or facilities. UC … [Read more...] about Career CX: Computer Science Demand Grows Exponentially

Here are the CODER regroup dates for Fall 2023 and Spring 2024. September 21 October 17 November 7 February 27: CODERS Competition Day. Bring your students. These meetings will all be held in the PSU Ballroom from 8:30-4:00. We plan on these meetings to be from 8:30-4:00. We know the student day will require some adjustments in time which we will figure … [Read more...] about 2023-2024 CODERS Regroup Dates

New STEM-specific scholarships ignite students’ ability to attend college. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded Missouri State University $1.5 million to provide scholarships to students interested in science, technology, engineering and math over the next six years. Submit your scholarship applications today. … [Read more...] about STEM Scholarships

About the Conference This year, the Write to Learn conference will be 100% virtual to better fit the needs of these ever-changing times. There will be national-level keynote speakers, bringing you some of the best language arts teaching strategies for these challenging times. Whether your school is going face to face, 100% virtual, or using a hybrid model, these mini-series … [Read more...] about Write to Learn Virtual Speaker Series

We want to encourage students to submit their writing, for publication as well as for scholarships. To that end, every session at this year’s Middle School Writing Conference – held on Friday, May 8 – will align with one or more writing competition categories outlined by the Language Arts Department of Southwest Missouri. LAD Fair, an annual competition hosted by the … [Read more...] about Middle School Writing Conference Meets LAD Fair

Last year's Middle School Writing Conference proved inspiring to say the least. On the morning of Friday, May 10, 2019, the buzz of voices subsided with the house lights in the Plaster Student Union Theater. Illuminated by the soft glow of the stage, hundreds of students leaned forward in their seats, eyes wide, several mouths agape, all submerged in a state of … [Read more...] about Writing. Community. Power.

Due to illness in our office, we had to cancel the Anna Julia Cooper transcribe-a-thon scheduled for February 14. However, we still encourage you to take a moment to celebrate Douglass Day in-between exchanging valentines this Friday. … [Read more...] about Douglass Day 2020

Did you know February 14 isn’t just for valentines? This Friday, join us anytime between 11 AM and 2 PM in Meyer Library 010B to help digitize the works of visionary Black feminist Anna Julia Cooper in honor of Douglass Day. Help preserve Black history and enjoy music and free food from Big Momma’s. … [Read more...] about Fall in Love with Cultural Competence

The photos from Write Now showcase the joy of writing and community in the Ozarks. We want to thank our inspiring keynote speaker, Shaun Tomson, and dedicated presenters, as well as the amazing teachers and students in attendance. We could not have done it without each and every one of you and we look forward to doing it all again at the Middle School Writing Conference on … [Read more...] about You ask. We deliver.

As you may have noticed, our High School Writing Conference has a new name – Write Now: A One-Day Conference to Engage and Motivate All Writers. This year, we not only invite high school students but those in University to share in the experience of a lifetime. We are thrilled to bring Shaun Tomson, best-selling author and world champion surfer, to campus again. Check out … [Read more...] about Not Just Rebranding, We’re Expanding

Nancy Allen, New York Times bestselling author and Missouri State faculty, will be presenting at the opening session of the 2018 High School Writing Conference held on the Missouri State University Campus. Allen’s latest book, Juror #3, co-authored with James Patterson, is a #1 New York Times best seller. Nancy Allen is the author of the Ozarks Mystery Series, published … [Read more...] about New York Times Bestselling Author at 2018 High School Writing Conference

About The goal of the College-Ready Writers Program (CRWP) is to assure teachers have the ability to teach college- and career-ready writing—with emphasis on writing arguments based on nonfiction texts. CRWP consists of school-embedded institutes; classroom demonstrations, co-teaching, and coaching; and study of effective practices in academic writing instruction, current … [Read more...] about College-Ready Writers Program; What is it?

By Colleen Appel In December, 165 high school students and their teachers from 18 school districts across southern Missouri converged on the Missouri State University campus for “Make Your Statement, Write Your Story,” a day-long conference sponsored by the Ozarks Writing Project (OWP), a project of MSU’s Center for Writing in College, Career, and Community (CWCCC). … [Read more...] about OWP Hosts Writing Conference for High School Students

Open Institute on Teacher Leadership Spring 2017 Study Away: Write Across Missouri Summer 2017 … [Read more...] about Unique Graduate Credit Opportunities to be Offered in 2017

At the first-ever High School Writing Conference on Friday, December 9, some of the most talented teacher-writers in southwest Missouri will conduct sessions designed to inspire students in grades 9-12 to Make Your Statement, Write Your Story. Session topics include script writing, parody, slam poetry, comic books and graphic novels, making money from writing, flash … [Read more...] about Make Your Statement. Write Your Story.

Congratulations to Heather Payne, co-director of Ozarks Writing Project (OWP), and Laurie Buffington, OWP teacher consultant and English teacher at Laquey High School, for being invited to share their experiences as teacher leaders during a webinar hosted by the U.S. Department of Education’s Investing in Innovation (i3) Community. The webinar, which took place on September … [Read more...] about Perspectives on Teacher Leadership from i3 Teacher Leaders

Julie Morris, English teacher at Macks Creek High School, has been named MSTA Southwest Region Rookie Teacher of the Year for 2015-2016. This prestigious award is designed to recognize the contributions of a classroom teacher of 5 years or less who is exceptionally dedicated, knowledgeable and skilled, and has the ability to inspire students of all backgrounds and abilities to … [Read more...] about Morris Named Rookie Teacher of the Year

Missouri State Poetry Society (MSPS) Youth Contest: The contest is free and open to students in grades 6-12. There will be three winners with cash prizes and seven honorable mentions awarded in each category. First place winners will be published in the MSPS Anthology, Grist. Winning poems and honorable mentions will be submitted to the Manningham Student Poetry Award … [Read more...] about Two Upcoming Opportunities for Youth Writers

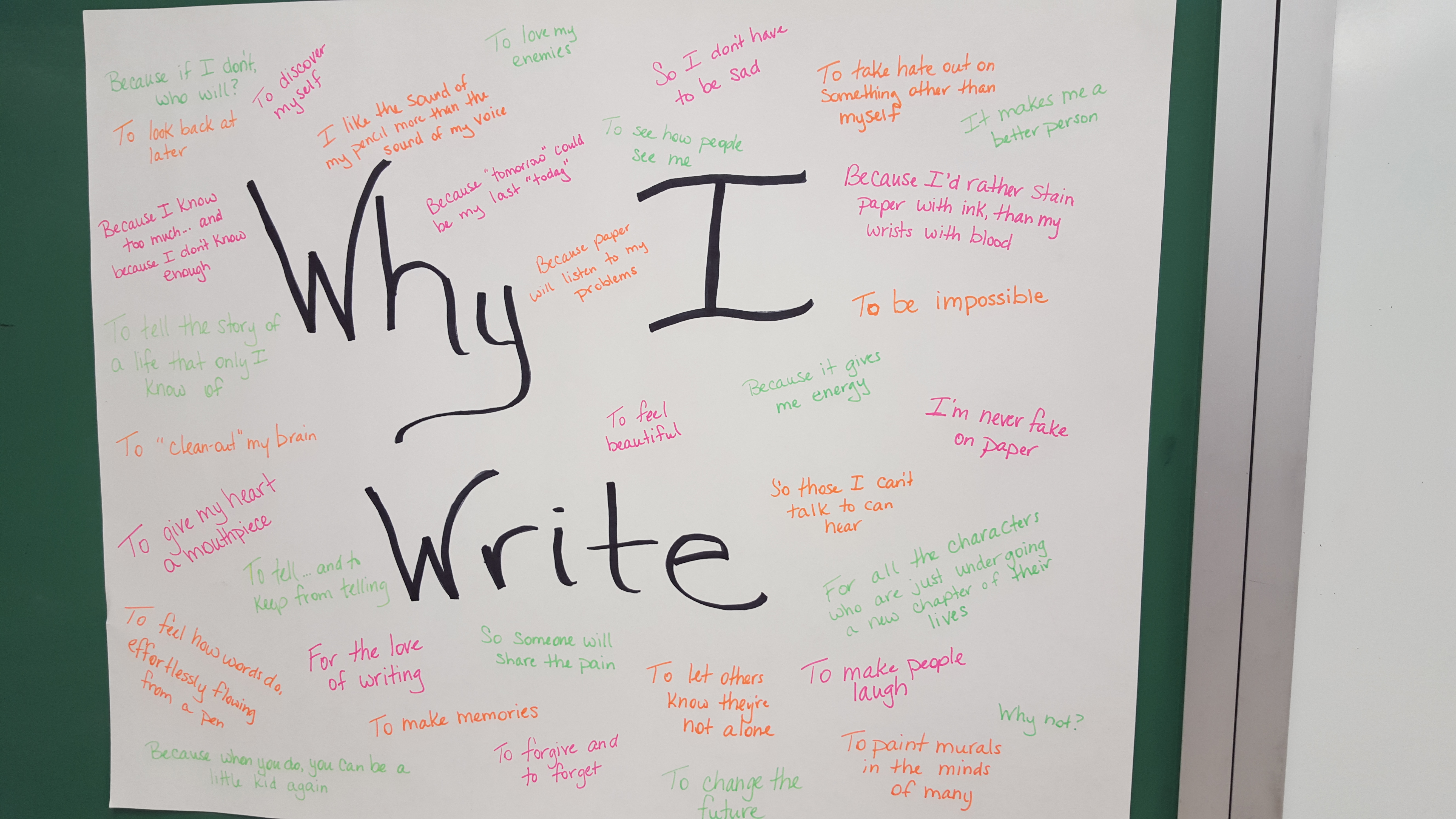

When Macks Creek teacher, Julie Morris, formed a plan to kick off her dual credit Creative Writing class with a “Why I Write” assignment, she was not anticipating an enthusiastic response from her students—they’re high schoolers, after all. But they surprised her. Looking back, Morris realizes she should have known the group of kids were capable of more than she—and often many … [Read more...] about “Why I Write” Assignment Results in Inspiring Poster

1. Summer Institute Nominations Teacher Consultants: Do you know an exemplary teacher (K-16, any content area) who should become part of the Ozarks Writing Project community? Does he or she desire to grow personally as a writer and deliver quality writing instruction in the classroom? Send names of nominees for the 2016 Summer Institute to Graduate Assistant Emily Duncan … [Read more...] about Four Ways to Get Connected with OWP

This is an excerpt of writing from the writing marathon that took place at Bennett Springs State Park on September 19. 2:37 p.m., along the stream between spring and river Families come to Bennett Spring, the one next to us a mother, father, and an eight-year-old son. Norman Rockwell, were he painting in Missouri this day, could do no better. The gnats, though, might tax … [Read more...] about Writing Marathon Writing by Terry Bond

This reflection was written in response to our OWP Fall Writing Retreat and Renewal at Bennett Springs State Park on Sept. 18-20. Reflection For the short time that I was there it was like coming home and being with my own kind. All of the teachers that I have been involved with have exhibited true professionalism and dedication. In the twenty years that I have been a … [Read more...] about Fall Writing Retreat Reflection by Karen Leonard

The following reflection was written by Dr. Gretchen Teague about the First Annual Ozarks Writing Project Fall Writing Retreat held at Bennett Springs State Park on Sept. 18-20, 2015. September 29, 2015 7:45 A.M. Back Home in Springfield, MO Remembering Fire and Water Thinking back, it is hard to imagine the first annual OWP Writer’s Retreat at Bennett Springs was … [Read more...] about Remebering Fire And Water by Dr. Gretchen Teague

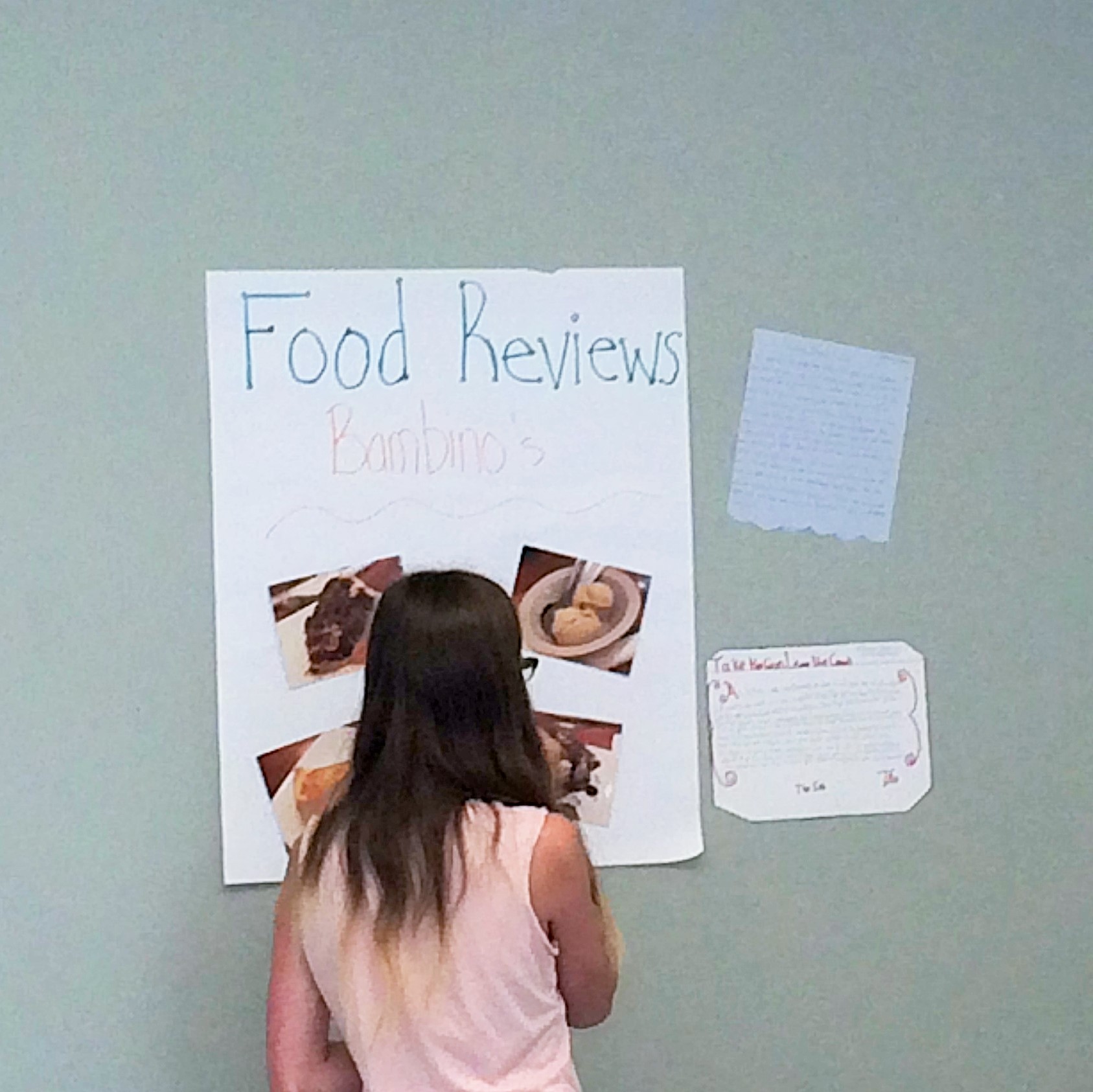

It's hard to believe the middle school camp is already over! The second week flew by with a flurry of field trips and Writing Workshops. From writing inspired by works at the Springfield Art Museum to food reviews of desserts at Bambino's Cafe to a Writing Marathon around downtown Springfield, the campers were out writing all over central Springfield this past week. For our … [Read more...] about Middle School Camp – Final Week and Author’s Chair

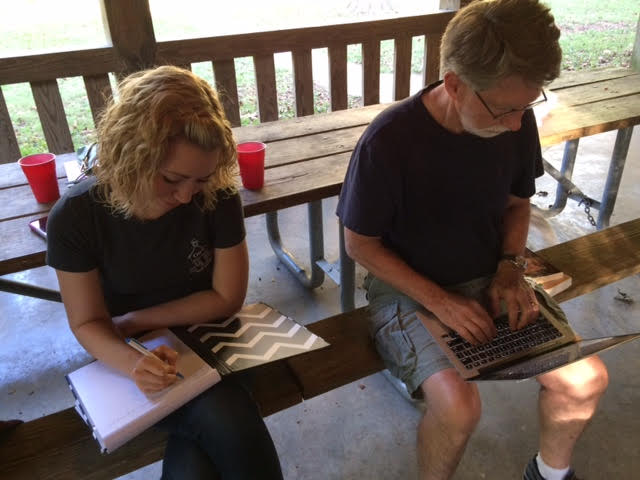

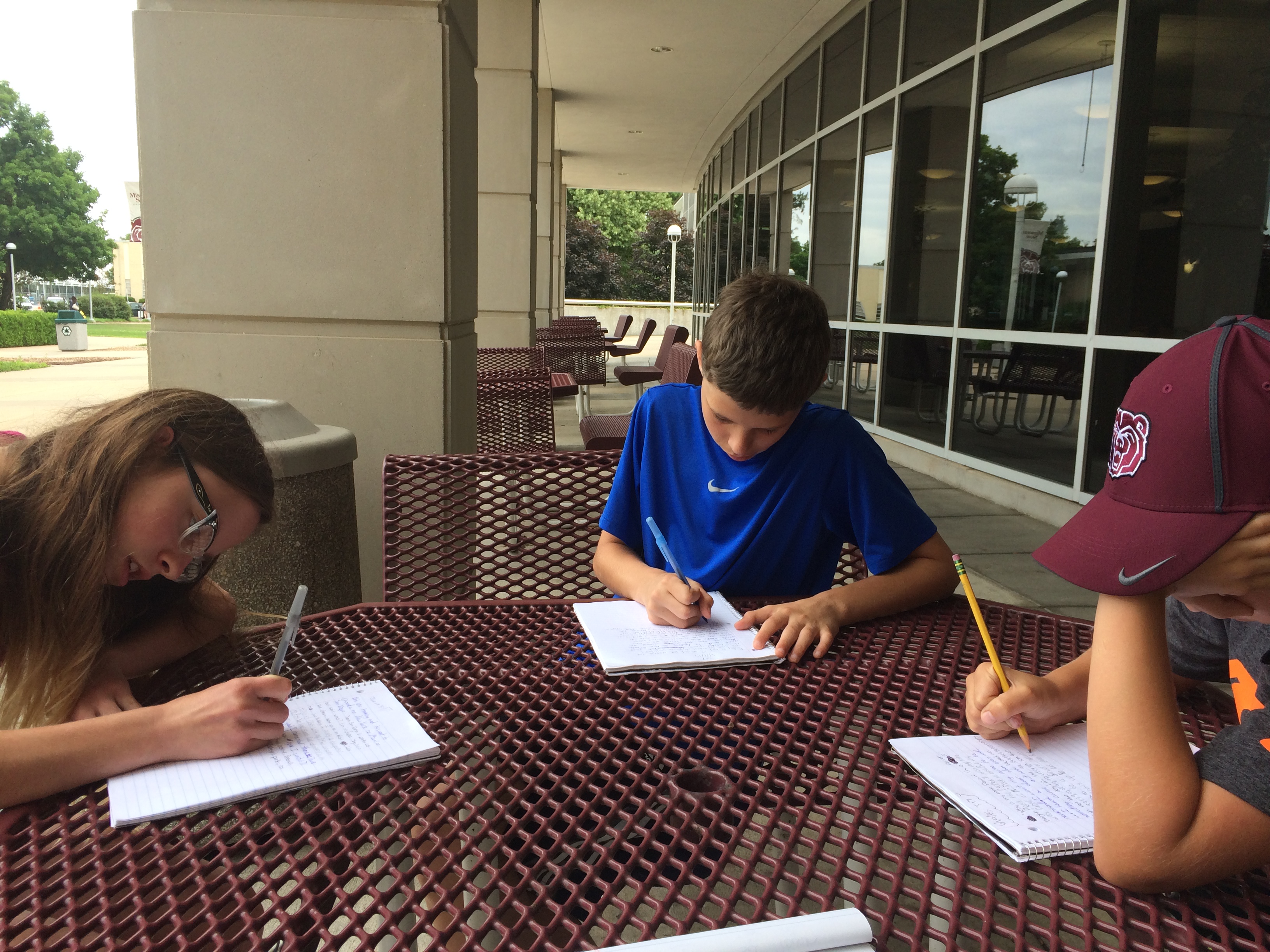

Our Middle School Youth Writing Camp is entering into it's second week! Last week, we tried our hand at poetry, short stories, altered books and more. We even braved the rain to do a nature photography scavenger hunt and place-writing! Friday, we did a brief Author’s Chair at the Park Central Library, where we shared a couple of original pieces … [Read more...] about Middle School Writing Camp – Week 1

Every day, like an annoying alarm, Jimmy walked by my room, stood in the doorway, and asked, “Do I have speech today?”. He had no sense of time, no idea of yesterday and tomorrow. Jimmy came to my classroom twice a week for thirty minutes at a time, and we worked on speech sounds and language concepts. Sometimes, when I felt he’d had enough of those, we worked on his … [Read more...] about Jimmy by Jana Parrigon, 2015 SI Teacher Consultant

The Ozarks Writing Project 2015 Summer Institute is just around the corner, i.e. June 8-July 1, 2015. With that in mind, I wanted to write to first remind local educators (in all content areas and grade levels) that we are accepting applications to the institute due on March 23. The instructions for the institute are posted on this website. I experienced my first summer … [Read more...] about Living Well: The Value of Teaching Place

Twelve teacher leaders are participating in a Teacher Leadership Workshop course throughout this spring semester. We are focused upon understanding more deeply what it means to be a teacher leader in our own classrooms, within our school district (or university) and within our local community. We are investigating what it means to become an advocate for our profession by the … [Read more...] about Planting Seeds: How Do We Grow as Teacher Leaders?

Today we met to prepare presentations for the Youth Writing Conference on May 8. Teacher-consultants Laurie Sullivan from Hillcrest High School and Tanya Hannaford from Mt. Vernon High School facilitated. The morning started with an excerpt from Terry Tempest Williams called "Why I Write." After listening to the reading, the 25 teachers from areas schools shared why they … [Read more...] about Why I Write: A Presenter Workshop for the Youth Writing Conference

Colleen Appel, Teacher-Consultant of the Ozarks Writing Project, describes professional development and student writing activities to teach on demand writing. Teachers across the disciplines are increasingly seeing themselves as teachers of literacy and understand the literacy practices in the content areas are distinct but overlap in a student’s daily literacy learning … [Read more...] about Writing on Demand: A Plan for Professional Development