Alchemy. The ancient desire to exchange the commonplace for the extraordinary — an impulse as understandable as it is unreachable.

But art and design professor Sarah Perkins has mastered a process that turns plain material into a shimmering work of art.

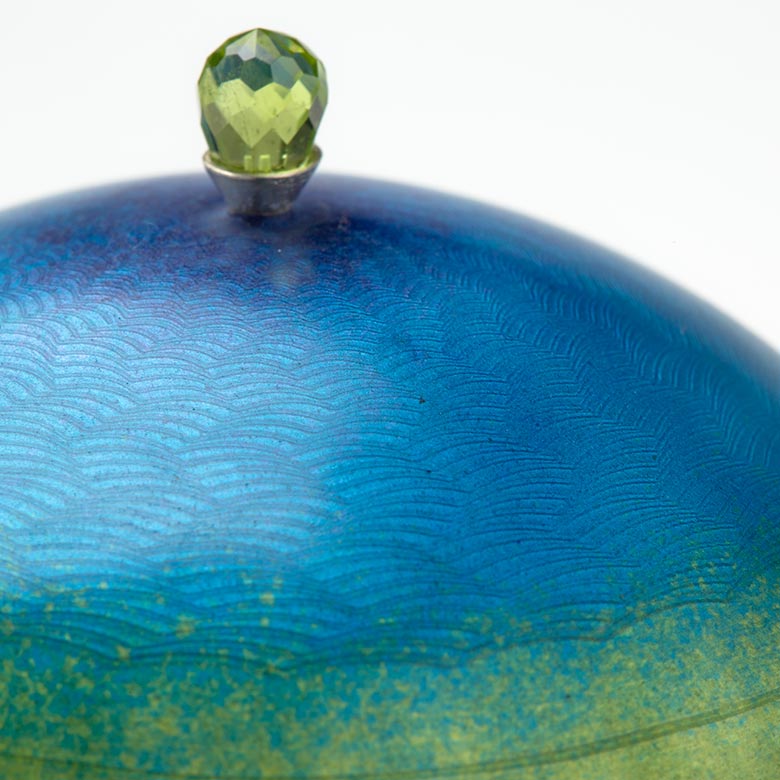

She begins with a thin sheet of metal, which she cuts and hammers into three-dimensionality. She uses fire to enhance the metal’s malleability. After many rounds of hammering, the sheet of metal has become a completed vessel.

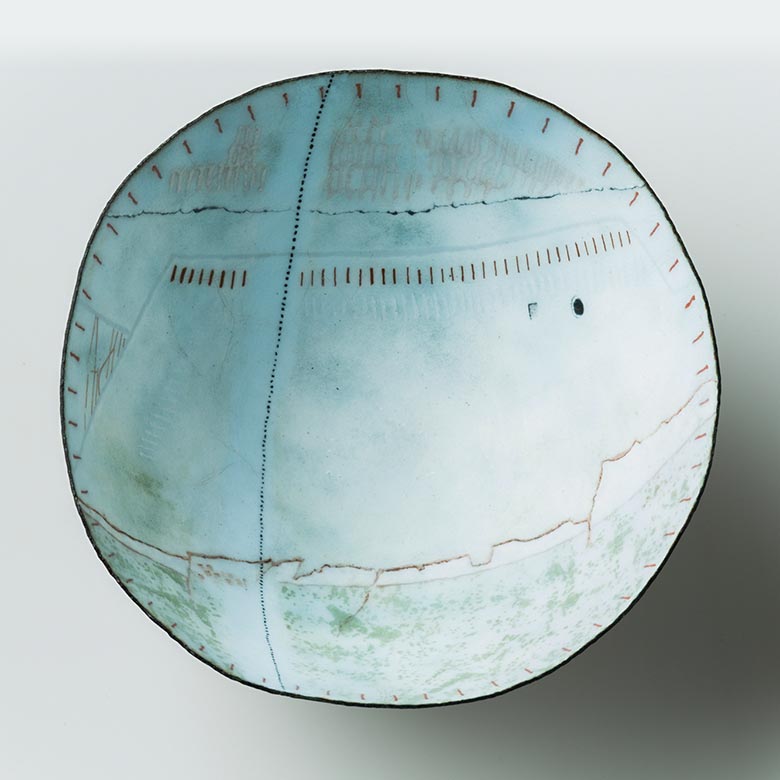

Next, Perkins showers the vessel with powdered enamel glass before firing it in a kiln as many as 30 times. The glass melts and fuses to the metal, creating an art piece with Perkins’ creative vision.

I look at a lot of historical work and reference it. Sarah Perkins

This process, which combines metalsmithing and enameling, distinguishes her art.

“I’m unique among metalsmiths because I enamel, and unusual among enamelers because I have a background in metals,” she says.

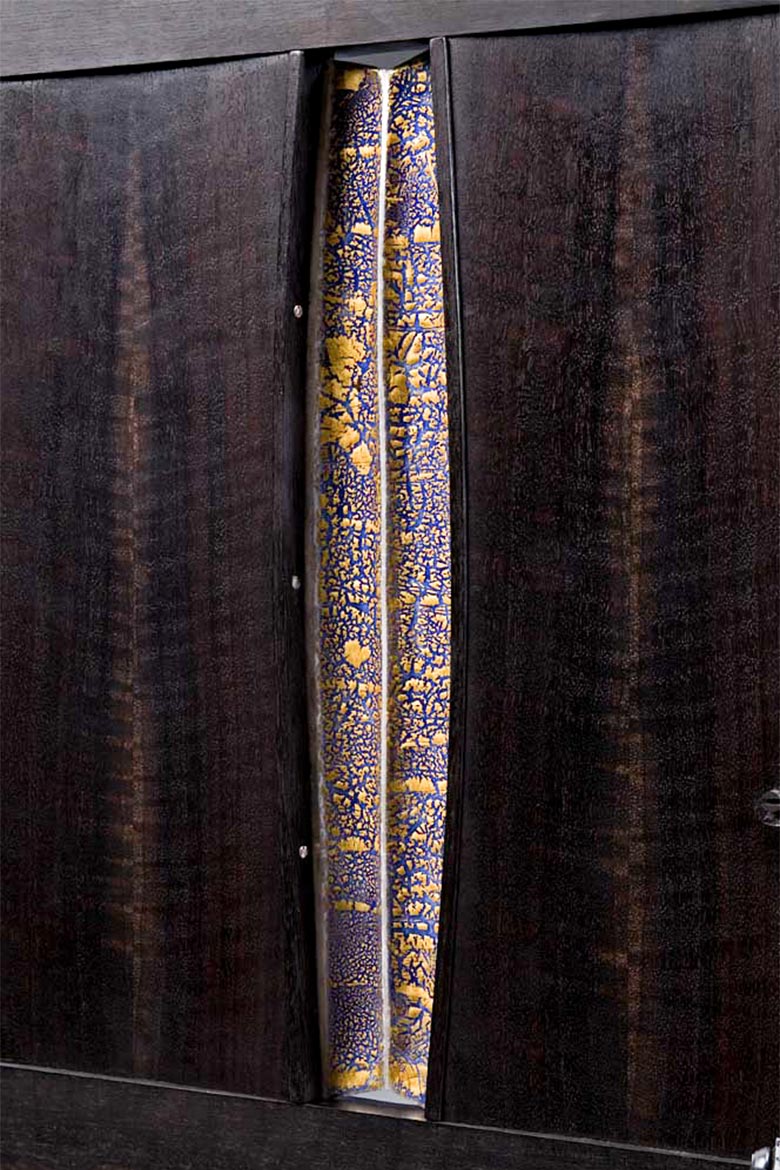

Cabinet maker Charles Radtke, who first met Perkins in the early ’90s before going on to collaborate with her, recalls being struck by her creativity and technique.

“I was drawn to her work immediately,” he says, “most drawn to the vessels she was creating. They seemed like little mysteries to me, the movement of landscape, the subtle textures and color changes.”

Collaboration with furniture maker Charles Radtke

Neither of us sketch, so we convey ideas and a vision that, through much talking and laughing, we come to a sense of the object. Our minds spin wild with possibilities because we know, in the end, whatever we dream up, we can surely make.

Charles Radtke

Global recognition

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”

The risks paid off, and her art has gained global recognition. She’s been the subject of solo exhibitions in Boston, Memphis, Tucson, Taipei and many other cities, and she’s slated for a solo retrospective in 2019. Her work is part of several public collections, including the Boston Museum of Fine Art, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Long Beach Art Museum and the National Ornamental Metals Museum, as well as about a dozen private collections.

A number of organizations, including the Enamelist Society, the Richmond Art Center, the Springfield Art Museum and the Midland Museum of Art and Science have honored Perkins’ work. Her history of awards recognition began in 1979 and continues to this day, in part because she still leaves room for experimentation.

“I’ve started firing dirt into the enamel to give it an interesting surface,” Perkins says. During a hiking trip to Montana, she collected sand, which she later incorporated into her enameling. “One of the sands had a lot of obsidian, which is a natural kind of glass,” she remembers, “so it actually melted a little bit.”

Travel provides visual cues as well. In India, the vibrance of traditional handicrafts inspired new color combinations and applications, and the black and white stripes Perkins observed near roadsides in Delhi emerged as a pattern in an exultant series of bowls.

Delhi Stripes series

One day riding around Delhi, India, I was struck by the patterned walls, and I started taking pictures of them. Later, as I looked at the photos, I realized, ‘That’s it. That’s my key.’ I felt like I had an entry into being able to represent what I was seeing there, and it was a completely different entry than I was expecting. Sarah Perkins

Delhi street scene by Sarah Perkins • Bowl photos by Tom Davis

A rebirth of enameling

Perkins is pleased that over the course of her career, respect for enameling has grown. She says, “In America, enameling was somewhat lost as a medium until after World War II,” when it was popularized in kitschy items, particularly ashtrays. According to Perkins, “We’ve had to push past that history of crafty trinkets,” and her innovation and advocacy have played a role in this success. “I think I’ve played a part in raising the profile of enamel,” she says.

As enameling’s stature has grown, so has its reach, which provides Perkins with opportunities to spread her artform. Through her Missouri State colleague Keith Ekstam, she connected with the Tainan National University of the Arts in Taiwan and began teaching workshops there.

I’ll have an idea of the piece, so I know basically what colors I’m going to use. But sometimes I’ll put a color down and go, “You know, I was going to put that chartreuse green there, but it’s wrong.”Sarah Perkins

“I was one of the first people – maybe the first person – to teach enameling there,” she says. “Many of my students were people who taught at other universities in Taiwan.” These instructors then began teaching Perkins’ techniques to their own students. “When I went back last spring, it had been about 13 years since I’d first been there. I learned that the enamelers there call me ‘Granny’ because I’m considered the teacher of the teachers.”

Perkins may sometimes marvel at her own evolution into a grande dame of her artform. “From an early age, I knew I wanted to be an artist and professor,” she says, “but I never told anybody because I was afraid I wouldn’t be successful. I tried to do other things until I realized I needed to just go for what I wanted.”

From those long-ago doubts to today’s accomplishments, it’s been quite the transformation.

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”

Her work has grown and evolved thanks to decades of practice, something she says her professorship at Missouri State made possible. “It allowed me to take a lot of risks and make some mistakes.”