Archive for April, 2020

Connections: Data and real life

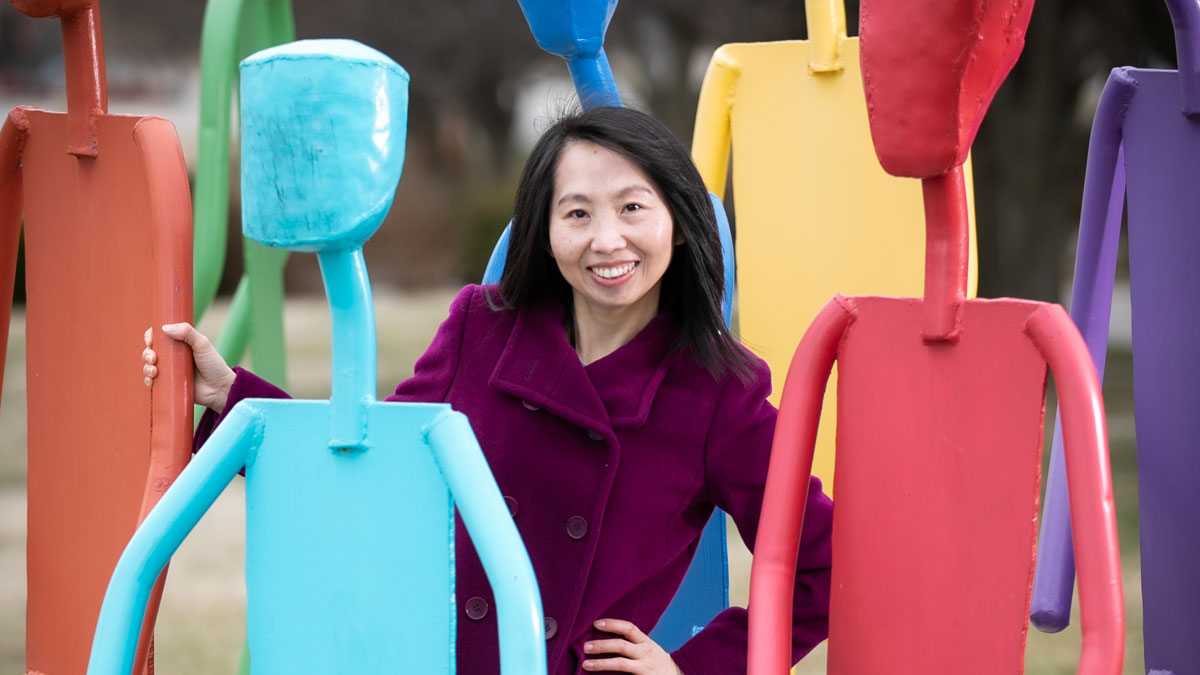

Qiu, associate dean of the College of Natural and Applied Sciences and a geospatial sciences faculty member, asked a logical question: Why don’t people spread out more evenly?

She imagined streets with less congestion. It felt like the perfect solution.

But it’s never quite that simple, she learned. You have to consider infrastructure, landscape, natural resources and other factors. Variables like these can influence how people interact with their environment and where they choose to live.

“Two scientists can look at the same set of data and have different insights.”

Now Qiu gathers and analyzes data to better understand the connections between variables and outcomes. Recently, this work resulted in several publications about determining potential sinkhole sites based on the collection of new elevation data.

“We’re trying to understand this world in a fully contextualized way, based on all the data and the methods,” she said.

In addition to studies on hazard vulnerabilities, she’s also interested in land use, health and population estimation.

What thread connects her varied research interests? They each have a personal and societal impact.

Predicting MAP success

As a mother with an interest in math, Qiu proposed another research question: What was the greatest contributing factor to successful math scores on the Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP, test throughout Missouri?

You might wonder how this relates to geospatial sciences. She explains that the first law of geography says everything is related. Things that are near to each other are more closely related.

Since students within a school district are physically close together, they are affected by many of the same variables.

“Seeing trends can help us more efficiently use our resources,” Qiu said.

After obtaining scores from 516 public school districts, she identified variables that she suspected might play a role in MAP test scores. She surveyed teacher credentials and explored census data.

The work of Dr. Xiaomin Qiu has practical applications. She answers questions that can inform policy. Her research can also influence resource allocation – to make the biggest difference to the communities that need it the most.

Would teachers who held master’s degrees be correlated with the highest achieving students? If a teacher had a math teacher certification, would the students reach peak performance?

Or did the family demographics have a greater influence? Would average household income play a role? How would the frequency of single parent households play into the score?

What’s the biggest factor?

Unsurprisingly, previous related studies showed a student’s attendance, participation and homework completion correlated with better test scores.

“Success is strongly determined by personal characteristics, like educational values, confidence and participation in extracurricular activities,” Qiu said.

But analyzing the data made one thing clear: School districts with the greatest household income had the greatest scores.

“When the area has more wealth, public schools receive more taxes, making them a more attractive school to land quality teachers,” Qiu said.

Due to the relationship between higher pay and higher levels of education themselves, Qiu says parents in these areas are more likely to pay closer attention to their children’s academic performance.

“Right now we have so much data. We can take full advantage of the data and produce some meaningful results for people to use. I think this is very important in this field.”

Across the region, though, the significance of individual variables changed.

In the southwest Missouri area, for example, the greatest relationship to student proficiency was parental education level.

In contrast, the greatest influence on math scores for northwest Missouri students was the number of parents in the household, with two-parent households being associated with higher scores.

This proved that one solution wouldn’t improve scores statewide.

“In the end, this study can give policy makers and administrators a new way to think about what they need in different schools,” she said. “We know income, or other influencing factors, are going to be at play, but how big is the role right here? This way you can customize a solution – one that is effective and efficient for your needs.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

A tale of two bats: One lives, one dies

It’s not as simple as falling asleep and waking up in six months. Bats go into torpor, which is a physiological state, unlike sleeping, where almost everything is shut down. Bats live off their body fat during that time.

Dr. Tom Tomasi, professor of biology, studies hibernating animals in torpor, especially bats.

Some species of bats develop white nose syndrome. It sounds cute, but it is decimating the bat population. More than a million bats have died each year since it was introduced in the United States in 2006.

White nose syndrome isn’t directly lethal. Tomasi compares it to when people get a rash. However, the bats die during or shortly after hibernation from this fungal infection. This is because it causes them to use too many calories in the winter.

Many bats reside in a cave at Sequiota Park. Dr. Tom Tomasi participates in an event there in fall 2019 and uses it as an opportunity to educate the community on white nose syndrome and bats.

Two reactions

Tomasi attributes the declining bat population to two things: white nose syndrome and torpor.

Bats can’t be in torpor all of hibernation. Every so often, a bat arouses out of torpor. The heartbeat speeds up. The body temperature rises. The bat may find a better spot in the cave.

“Bat females generally produce one pup a year. If that pup survives, it’s going to take a long time to get back up where it needs to be.”

Some bat species that get white nose syndrome, like the tricolored bat and northern long-eared bats, arouse more often than healthy bats. The more they come out of torpor, the more body fat they burn. The bats that arouse more often run out of fuel and die.

Other species of bats, like grey bats and big brown bats, seem to ignore the infection and arouse at the normal rate. They fight off white nose syndrome in the spring when they end hibernation.

Drs. Tom Tomasi and Christopher Lupfer examine a bat at Sequiota Park.

Down to the genes

Why are some bats triumphing over white nose syndrome and others are dying at alarming rates?

Tomasi brought in Dr. Chris Lupfer, assistant professor of biology, to look at the immune system.

“We’ve been looking at whether or not the immune system will explain why some species are 75-95% gone,” Tomasi said. “Other species, their numbers don’t change.”

Together with students who work in their research lab, they found six immune-function genes that are expressed more in species affected by white nose syndrome.

Bats, like this one, are susceptible to white nose syndrome. Drs. Tom Tomasi and Christopher Lupfer are identifying the genes that allow some to survive.

The bats who are dying turn on those genes before or during torpor. The bat species who are surviving wait until spring to turn on the genes to fight the syndrome.

“The immune system of the susceptible species tries to turn on and protect the animal, which doesn’t work,” Tomasi said.

Lupfer has enjoyed combining his interests: immune systems and going outdoors.

“And the bats that seem to say, ‘all right, it’s grown on me, but my immune system is not going to turn on and try to defend myself until spring’ are the ones that survive.”

“Bats are cool,” Lupfer exclaims. “It’s been exciting to work with bats and get out of the research lab and into the fields and caves.”

Lupfer has partnered with Tomasi for the past three years. With more than 30 grants and 35 publications, Lupfer wryly observes that Tomasi has groupies.

“Everywhere we go, someone wants to pick Dr. Tomasi’s brain,” Lupfer said.

Volunteers work alongside the team from Environmental Solutions and Innovations to record data on the bats living in Sequiota Park.

What it means for the Ozarks

“We used to have 500-600 bats in a cave I looked at with the Missouri Department of Conservation,” Tomasi said. “When we were there a couple years ago, we found 45.”

Tomasi and Lupfer have traveled to Oklahoma, Utah, Arizona and other states to find and protect bats.

“So that same bat that survived the wintertime and repaired the wing damage, got rid of the fungus during the summer, the next winter when it’s going to hibernate, it could get it again.”

Lupfer adds that this research can prevent other areas from being as harmed by white nose syndrome.

“In the western United States, white nose is just starting to pop up,” Lupfer said. “If we can use our research to predict which bats are more likely to die, then wildlife managers can take steps to protect those bats now.”

- Story by Tori York

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Gawat