A turtle’s tale of survival

Submitted by Dr. Day Ligon

One such species is the alligator snapping turtle which, after decades of population declines, has been petitioned for federal listing as an endangered species three times. The most recent petition is currently under review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These large turtles are of particular interest to Dr. Day Ligon, associate professor of biology at Missouri State University, who has published prolifically about them.

His specialty is reintroduction biology – a subset of conservation biology – that works to increase populations of animals by reintroducing them in their historic range to re-establish populations that can sustain themselves without human intervention.

Who’s to blame for this depressed number of alligator snapping turtles? According to Ligon, channelization of rivers and construction of dams have had huge impacts.

So, too, has people’s affinity for turtle meat. As other large species, such as sea turtles, were granted protection from commercial harvesting, pressure on alligator snapping turtles to fill this niche market increased. As a result, alligator snapping turtles were harvested at much higher rates than populations could sustain.

In practice, these and many other turtles are sensitive to even low harvest rates because they take so long to mature and begin reproducing. It can take decades for a population to recover from the removal of even a few large adults.

Photo by Kevin White

Below the surface

Alligator snapping turtles, which are endemic to the southeastern United States, can solely be found in the rivers that flow into the Gulf of Mexico.

“They’re big, impressive, ugly-but-charismatic turtles that almost nobody ever sees, because they’re so highly aquatic. They probably spend less time on land or basking on logs than any other freshwater turtle species in the United States,” said Ligon.

Due to this aquatic nature, these turtles don’t move around dams easily. In the rivers that feed into the Gulf of Mexico, many dams exist, making it next to impossible for a population to become reestablished after it’s been cleared out. However, if the habitat is otherwise in good condition, animals reintroduced into these isolated river segments often can thrive.

Unfortunately, restoration ecology is becoming a more and more important discipline because habitats are not being preserved at an adequate rate.

Submitted by Dr. Day Ligon

Ligon, along with his graduate students, spend the summers at the Caney River on the Kansas and Oklahoma border and at Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery in southeastern Oklahoma – run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – studying the secret underwater lives of alligator snapping turtles. This progression of research projects, funded by more than half a million dollars since Ligon joined Missouri State’s faculty, continues to fill in gaps of knowledge, allowing for more informed conservation management decisions.

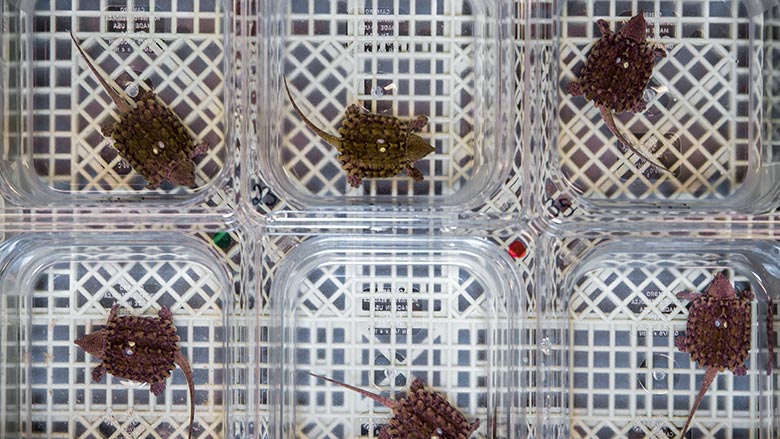

In 2002, Ligon joined forces with this fish hatchery, which at that time had 16 adult alligator snapping turtle in its captive breeding program. In 2008, they began releasing animals back into their natural environments. Now, they produce 500-600 hatchlings each year, keep them in captivity until they have grown and are less prone to predation, then release them into areas where the species has disappeared.

When the animals are released, Ligon and his team continue to gain information on critical research questions.

“We learn a lot about how many of them survive, how fast they grow and when they start reproducing,” said Ligon. “Once we start seeing reproduction, and then ultimately recruitment of new animals into the population that we didn’t put there, that will be the point at which we can really start saying with some confidence that it seems to be working.”

“If you see a snapping turtle crossing the road, it’s not an alligator snapping turtle — ever.” — Dr. Day Ligon

Submitted by Dr. Day Ligon

According to Daren Riedle, Ligon’s collaborator and ecologist at the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism, “Ligon’s research program is unique as it is one of the few that takes experimental approaches to addressing questions of physiological ecology, particularly reproductive biology, and makes it applicable to applied management of the species in the wild.”

Kerry Graves, manager of Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery, also notes Ligon’s unique approach to work.

“I don’t think Day wore shoes any of the first 10 or 12 years of our partnership. He was barefoot in all types of weather and on all types of terrain – including wading in the alligator snapper ponds. I was concerned about his brain and his toes until I got to know him,” said Graves.

Photo by Kevin White

Reintroduction success

Scientists can determine the age of a tree by the rings in the trunk. Human age can be estimated by wrinkles, size, life experience, or, from a biologist’s perspective, by analyzing the telomeres of chromosomes. But determining the age of a turtle is complex. Their shells show growth rings (similar to those of trees) until they reach the age of sexual maturation, but after that initial growth period, their age is a mystery.

Photo by Kevin White

“For young alligator snapping turtles, we can tell how old they are pretty precisely – within a year,” he said. “Growth just drops off precipitously as they start re-allocating energy to reproduction.”

The first hatchlings Ligon assisted with in 2002 are just now old enough to become reproductively active. Because of this, major impacts to populations may not be evident for another generation. In fact, noted Riedle, studying one population is a lifetime endeavor on the part of the researcher.

“The most gratifying portion of the research has been seeing these turtles reintegrated back into systems where they historically occurred, but from which they’ve been absent for decades,” he said. “To see them become reestablished and become a part of the overall aquatic community again is very, very rewarding to me.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Carter Williams