History and memory: Making peace after religious conflict

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Throughout the better part of the next three decades, Protestants engaged in iconoclasm, or the destruction of religious images and relics, as they believed their reverence was a form of idolatry. In the process, they demolished a multitude of sites and artifacts sacred to Catholics.

But what happens after the dust settles?

“My real interest isn’t in the smashing of the relics. I think that story is pretty straightforward,” said Dr. Eric Nelson, professor of history at Missouri State University. “It’s what you do after something like that happens. I think that’s where the story can unlock a whole new set of ideas.”

History and memory, according to Nelson, are two very different ways of remembering the past. While the history of these battles illuminates the divide between Catholics and Protestants, the memory of what happened has the ability to reconcile differences between the two sides.

How does this happen? This is Nelson’s primary research question and has been at the root of his recently published monograph “The Legacy of Iconoclasm: Religious War and the Relic Landscape of Tours, Blois and Vendôme 1550-1750.”

“Once blood is shed over religious ideas, it’s very difficult to make peace,” said Nelson. “I’m interested in peacemaking after violent religious conflicts.”

Pillaged and plundered

Saint Francis of Paola, born around 1416, was the founder of the Minims, a Roman Catholic order of friars.

Francis, a renowned healer and miracle worker, spent much of his later life in Tours, France, where a Minim monastery would eventually be built. Francis died in 1507 and was later canonized by Leo X in 1519.

On April 2, 1562, Protestant forces captured the city of Tours, and on April 7, they seized the Minim monastery. During the looting, troops forced open Francis’ tomb and cremated his remains, destroying the precious relics of the order’s founder.

While this account of the events of the day is truthful and factual, it is very different from the story that Nelson had come to know.

Submitted by Dr. Eric Nelson

A saint and a martyr

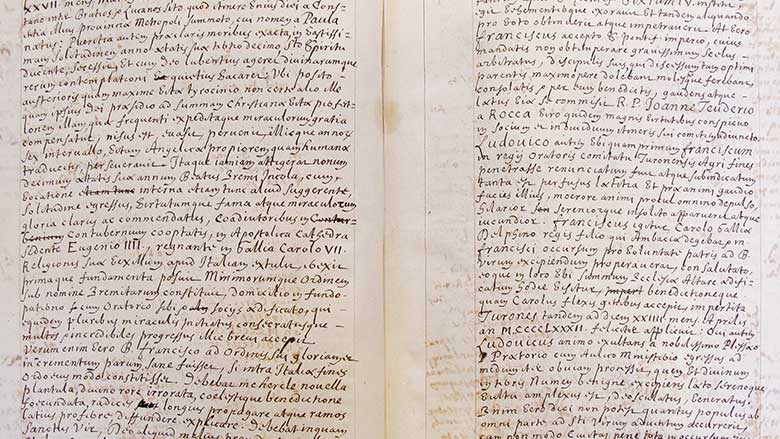

Nelson, who has studied European religious history for over a decade, discovered stark differences between what he thought happened and what actually happened by visiting sites of iconoclasm in Europe and diving deep into the archives of Tours and the Vatican.

“After going back to the documents in the actual archive, I realized almost nothing about the Minim version of the story is actually true,” said Nelson. “But the story they came up with was much better than what actually happened.”

In their account of the burning of Francis’ remains, Minim historians assert that Protestants failed in their effort to weaken devotions to the saint. Instead of a victory for the forces of evil, the burning of his body represented God’s good will and favor toward the saint, allowing him to rise to the title of “martyr.”

Evil men, as one Minim historian concluded, became “the instruments for the honor and glory of our Saint.”

Peace through memory

Submitted by Dr. Eric Nelson

As Nelson compared notes between the two accounts, he discovered a profound intersection between history, memory and peacemaking.

“Francis’ grave was desecrated — his bones were burnt and spread to the winds,” said Nelson. “If the Minim had to stick to what actually happened, it’d be much harder to make peace. Instead, they focus on a much more positive point of view.”

As a member of the international Sixteenth Century Studies Society, Nelson’s discoveries are helping reshape the narrative of early modern French and European history, according to Dr. Amanda Eurich, professor of history at Western Washington University.

“His imaginative insights allow us to recapture the spiritual worlds of the past,” said Eurich. “It reminds us that the religious violence and iconoclasm wars not only marked the physical landscape of France, but also cultural memory for generations.”

“People think of history as a series of events that happens that you memorize and then there’s a test and you’re done. In reality, history’s a living thing. It’s always evolving. Every generation writes its own history.” – Dr. Eric Nelson

According to Nelson, this reimagining of history is powerful: “What people think happened is sometimes far more important than what actually happened. The real reality is the story they constructed — that’s the power of memory in peace making.”

Knowing how history evolves and is shaped by memory is paramount to today’s society, because religious violence is with us for the foreseeable future.

“We know how to get into religious wars just fine — we can start them really easily,” said Nelson. “It’s how you get out and make peace afterwards — that’s where the real lesson is learned.”

- Story by Zachary Riel

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

2 Responses