Posts Tagged With ‘College of Humanities and Public Affairs’

Uncovering the truth and the trauma

When Dr. Marnie Watson’s career as a novelist didn’t pan out, she sought a new path where she would unveil truth about humanity and culture.

As a cultural and medical anthropologist, Watson immerses herself in her research, where she draws close to people in extreme circumstances. She asks questions to better understand, “how they deal with life in difficult situations.”

Much of her work has dealt with illicit drug use, mental health, poverty, homelessness and involuntary migration.

In 2022, she finally realized her dream of publishing a book – this time, about one of her research projects.

A moving career

Watson, now an assistant professor of anthropology at Missouri State University, characterizes her jump into this field as naïve.

“I was completely out of my depth,” Watson said.

It was fortunate, though, that as a graduate student, her advisors saw potential in her. Immediately, her research led her to meet individuals with behavioral health issues.

Those early studies showed her how meaningful the work was but also how emotionally taxing it would be.

“There were days I went home and I would tell my partner, ‘I made every single person I talked to today cry.’”

She also found that trauma serves as a common breeding ground for substance abuse.

“One hundred percent of the people I studied had suffered horrific trauma in their backgrounds,” she said. “That shifted my perspective on mental health and substance abuse.”

These experiences prepared her for a study with Nepali/Bhutanese refugees who were resettling in Akron, Ohio. This research is chronicled in her 2022 book with Dr. Pritha Gopalan, director of research and learning at Newark Trust for Education.

The head of social services at a local refugee resettlement agency, Radha Adkihari, reached out to the University of Akron, where Watson was teaching at the time. Adkihari asked for assistance in understanding one primary question: Why are there so many cases of alcoholism or alcohol-related injuries in the Nepali/Bhutanese refugee population?

“They said, ‘We’ve never seen anything like this. This group is off the charts,’” Watson said. “They were seeing advanced alcoholism in little old ladies, a lot of domestic violence, terrible car accidents and a lot of DUIs.”

Looking into the refugee experience

To prepare for this anthropological study, Watson first had to soak in the history of the Nepali/Bhutanese refugee camps established in the 1990s. At that time, many fled Bhutan due to an oppressive government. They sought asylum in Nepal.

“These people were in refugee camps for 20 years before they were resettled to the United States,” she said.

It’s not as simple as relocating families in the U.S., Watson noted. The government resettlement program doles out funds and assigns groups to settle in these designated locations, at times breaking up extended families in the process.

Watson advocates for preserving extended families in the resettlement process. Through intact kinship systems, refugees coordinate elder- and childcare, transportation and employment. These relationships also provide financial, psychological and emotional support, which are crucial for community and social integration.

To address the question of substance abuse, Watson enlisted the help of an interpreter – Santa Gajmere, who Watson called “a cultural broker” – to better communicate with these individuals.

The more they spoke with the people and learned about their heritage and situations, the more they realized the incredible diversity among the Nepali/Bhutanese refugees. This included multiple languages and dialects, religious differences, as well as caste and class differences.

“The resettlement program is causing a lot of trauma. Refugees have their original trauma from the events that led them to being refugees, and this whole set of traumas that came from living in the refugee camps. Then they were traumatized again when they were resettled to the U.S.”

Within those categories, there were different relationships with alcohol, too – some of which distinctly prohibited drinking.

A voice for the voiceless

While offering a resettlement program seemed like a humanitarian effort, Watson found parts of the program itself and the dispersal policy in particular problematic. Many individuals were isolated from their support systems, had difficulties integrating in the community and struggled to find meaningful work.

Ultimately, Watson discovered the program was part of the cause of the trauma that led to substance abuse issues.

“There are layers of trauma that accrued over time,” Watson said. “While you’d think that resettlement might be a purely positive experience, the way it is often done causes additional trauma. That is what people more often would talk about.”

Gopalan applauds Watson’s fieldwork, empathy and commitment to equity. The flaws in the system exposed in this study could easily be avoided, she noted, if people with direct experiences as refugees were included in the development of solutions.

“Their perspective is rich, layered and steeped in their experiences,” Gopalan said. “By employing strengths-based perspectives and discourse, we benefit from the refugees’ experiences and ideas, rather than patronizing them or casting them as helpless victims.”

Happiness in a small community

In Springfield, Missouri, Watson works with the previously unhomed at a tiny house community, Eden Village.

“Eden Village is built on the housing-first principle, which means, ‘Come with all your problems. You don’t have to sort anything out ahead of time,’” she said. “Once you’re housed, everything is easier.”

Watson is assessing whether residence at Eden Village improves quality of life.

More than that, though, she’s getting the insider view to understand the worldview of community members, which is what all true anthropologists do. She participates, observes and asks questions to get a deeper and more well-rounded perspective.

Telling the stories of the people she studies has fulfilled Watson’s purpose of uncovering universal truths – something she once thought possible through a career as a novelist.

“A little bit of anthropology is good for you,” she said, “because it is the ultimate study of how you are not the center of the universe.”

Further reading

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Taxes in Latin America: More than dollars and cents

Perhaps a third item should be added to the list, Dr. Gabriel Ondetti says: People believing they pay too much in taxes … especially in the United States.

“When you tell them what the data says – that they’re very lightly taxed compared to people in other countries – they’re astounded,” Ondetti said.

An expert in Latin American politics and taxation, Ondetti has published two books, authored more than 30 conference papers and contributed eight articles in refereed journals. He is the Clif and Gail Smart professor of political science and director of the Master of International Affairs program at Missouri State University.

His central research question is: Why do some countries tax their citizens more heavily than others?

“A lot of people find taxation boring because it can be highly technical,” he said. “But it’s a political process. You can understand many other things about a country by studying taxation.”

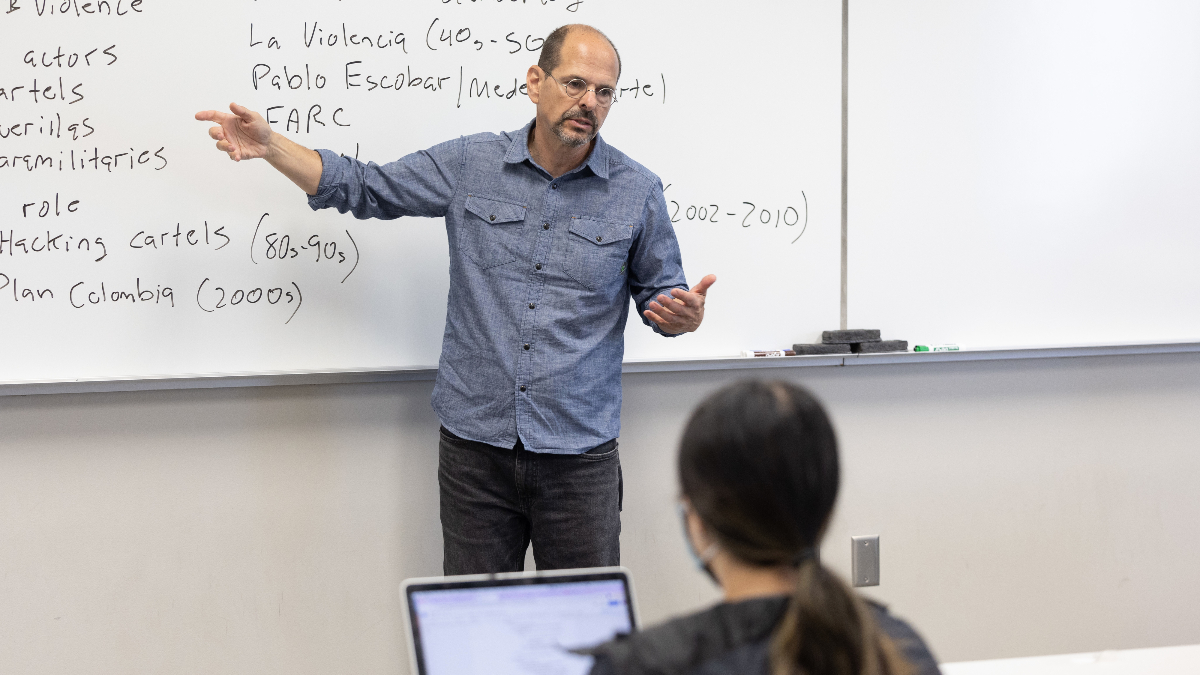

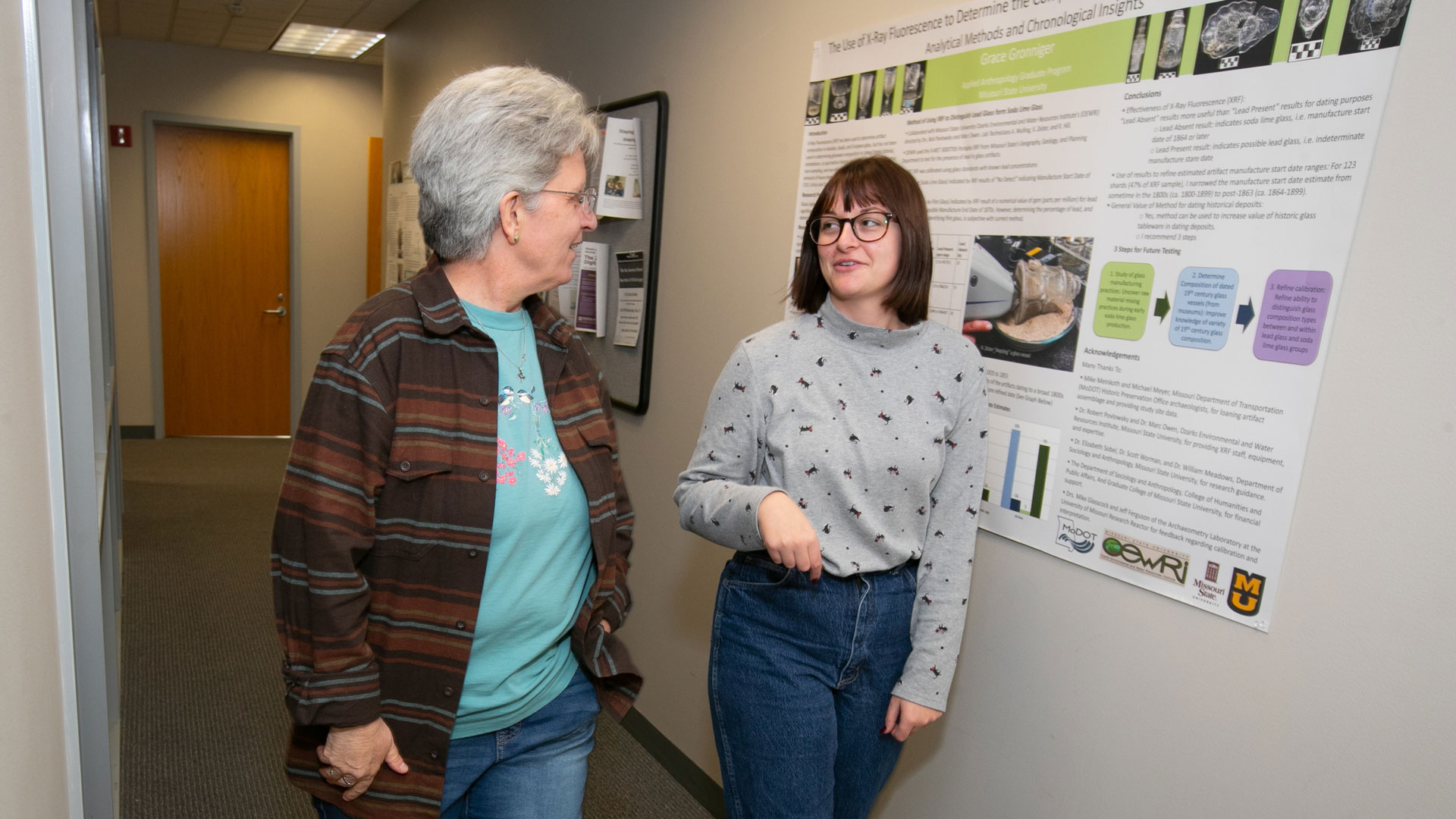

Student Tracy Ramirez poses a question to Dr. Gabriel Ondetti.

Uncovering the roots of taxation in Latin America

In 2021, Ondetti published “Property Threats and the Politics of Anti-Statism: The Historical Roots of Contemporary Tax Systems in Latin America.” The refereed work won an award from the Latin American Studies Association and delivered outcomes from Ondetti’s qualitative research, including more than 80 interviews with politicians, business leaders, and other decisionmakers.

Ondetti’s parents immigrated to the United States from Argentina in 1960. That sparked his interest. Some of the key questions came about during his 10 years of work on taxation in Latin-American countries. Why is taxation heavier in Brazil than Chile? Why is it heavier in Argentina than in Mexico?

“If you’re a political scientist, you can’t really ignore taxation. Whatever government does, they have to have money to do it.”

Using a qualitative and comparative historical method, Ondetti found that countries with lower tax rates tended to be countries that historically threatened private property by seizing land, oilfields, factories and other assets on a large scale.

A redistribution of property rights in favor of the poor, Ondetti says, resulted in a long-lasting political backlash from the wealthy.

“The very act of redistributing property through land reform and nationalization of private industries inspired strong anti-government ideologies, particularly among elite sectors of the population,” he said.

But lower taxes mean less public funding for items such as education, social programs and infrastructure, which creates something of a paradox, he said.

“It’s kind of ironic, you know? The places where people sought the most progressive change became the places that created the greatest obstacles to change.”

Ondetti’s work is special in many ways, according to Dr. Gustavo Flores-Macías, associate vice provost for international affairs and associate professor of government at Cornell University. Flores-Macías shares the same research interest and is familiar with Ondetti’s book.

An expert in Latin American politics and taxation, Dr. Gabriel Ondetti has published two books, authored more than 30 conference papers and contributed eight articles in refereed journals.

“I think research into taxation has been dominated by economists for the most part,” Flores-Macías said. “Two of the great things Gabriel does is explore how to make taxation politically palatable and focus on explaining differences within Latin America.

“Several people have written about Latin American taxation compared to European countries, but it’s a lot more complex to look within a region. He does careful, historical tracing of the reasons behind those differences.”

Taxes in the United States: Not as high as you may think

People from every country think their taxes are too high. That’s especially true in the United States, Ondetti said, where citizens have little idea how their taxes compare to other countries.

“The tax system for many countries is deeply intertwined with a whole series of other factors that shape their culture and politics.”

Taxation is essential for countries everywhere to provide services, but the questions governments must answer include: Who’s going to bear the burden? To what extent will those people rebel, and what consequences could that bring?

“That even includes Mexico, which has the lightest tax burden of all the countries that I studied. Everybody there thinks they have very high taxation,” he said.

As an example, Ondetti notes that the United States has one of the lowest tax burdens among all developed countries. It’s equal to about 24% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country during one year.

By comparison, Denmark’s tax burden compared to their GDP hovers around 45%.

“Yet, there are probably more people in the United States who feel they’re overtaxed than there are in Denmark,” he said. “That’s a subjective judgement, which they have a right to. But in comparative perspective, it just isn’t true.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Relating stories of the ancient world

So, it was only natural that Troche, an Egyptologist, chose to study history in college. She delved deep into the realm of ancient Egypt and Assyria in graduate school.

Over the years, she has visited the region several times to conduct research and field work. She has spent time in Abydos and Luxor in Egypt and Petra, Jordan.

Treating the dead like gods

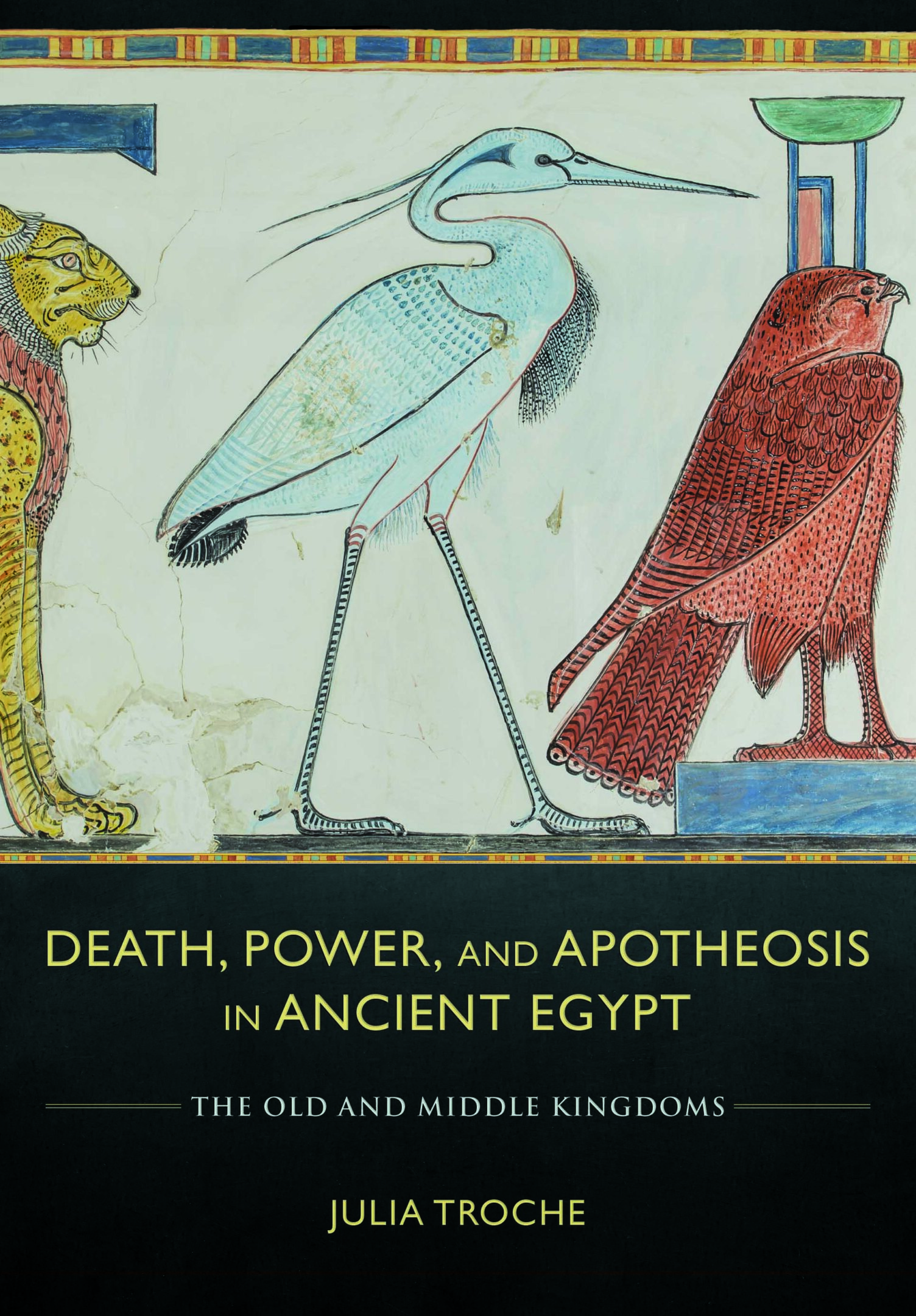

Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms by Julia Troche

One of her main research areas examines the intersection of religion and society in the ancient world.

“This involves thinking about how religious and social practices, norms and ideology confronted each other or worked together,” said Troche, an assistant professor of history at Missouri State University.

Her latest project is her first book titled, “Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms.” It builds on her dissertation research about glorifying the dead in ancient Egypt (around 2700-1650 BCE).

Drawing from resources like ancient inscriptions, artifacts and literary works, the book explores how ancient Egyptians created, kept and challenged power through:

- Mortuary culture – practicing specific rituals and giving offerings to the dead.

- Apotheosis – elevating the dead to god status.

Troche studied people during that era who treated their dead as gods – going beyond ancestor worship. She explored how they used their esteemed dead to negotiate social, religious and political capital.

“People were asking them to do things the normal dead weren’t asked to do such as ‘Can you get me into the afterlife?’”

She notes that was something only the king did before, and it challenged the king’s power and authority.

“These deified dead were now able to do things that were once reserved exclusive to the king,” she explained. “So, it’s this interesting power play.”

In Petra, Jordan, Dr. Julia Troche participates at an archaeology site.

Looking at power from both sides

A key goal of Troche’s research is to analyze and present information from a different angle than the way it has been taught or described in publications.

That’s why in addressing power in her book, Troche includes both top-down and bottom-up power. Instead of focusing only on the king’s actions, she also highlights what the elites and other Egyptians did.

“When we think about power, we don’t just look at the one in charge. We also have to think about all the other people – the subjugated others,” she said. “It doesn’t mean they don’t have agency and power because they’re subjugated.”

Exploring past and present pedagogy

Another focus area for Troche is on the practice of teaching. She researches “pedagogy both in and of the ancient world.”

“I want people to gain an appreciation for ancient Egypt and the ancient past, just for the sake of that ancient culture.”

Recently, Troche completed an article about virtual reality storytelling. It’s based on a collaborative project with writer and performer Eve Weston.

They created a proof-of-concept video game called “The Spirit of Egypt.” It uses virtual and augmented reality to teach about ancient Egypt through storytelling and humor. The game features the funeral of Hatshepsut, one of the most powerful female pharaohs.

In the article, which focused on using the game for instruction, Troche argues that modern historians can and should use nontraditional ways to teach and engage learners.

Dr. Julia Troche and Dr. Kathlyn Cooney, UCLA, pose with students at 2019 Nelson Atkins event.

“Humorous and quirky things may not be proper academic pedagogy. But they are useful teaching tools, especially for college students,” she said. “You help people learn better by engaging with the things they love.”

Another one of Troche’s recent collaborative efforts revolved around science fiction. This time, she worked with fellow Egyptologist Stacy Davidson from Johnson County Community College on a project about Star Wars’ Force ghosts. They compared the ghosts to the ancient Egyptian Akh – the effective spirit of the deceased.

“Since Julia’s an expert on the Akh, I wanted to know how similar or different it was to the ghosts,” Davidson said. “It was clear we could use concepts in popular culture to open up new avenues for research and teaching.”

They created a video of their research. This past summer, they presented it virtually at an international conference on sci-fi in ancient Egypt.

Troche notes using Star Wars as a teaching tool works because it’s accessible and popular.

“Many people are familiar with the series and feel strong emotions about it. You can activate and build on that knowledge and emotion,” she said. “Then, use that as a launching pad to talk about ancient Egyptian concepts like spirits, the afterlife and rebirth.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Code talking: Shining a light on war-time heroes

Meadows, professor of anthropology and Native American studies at Missouri State University, works with many Native American tribes and cultures. He also studies Japan.

From a military family, early in his career he became interested with the military experience of indigenous peoples.

As he unearthed more about the ceremonies, music and art associated with these veterans, he discovered a largely unstudied area of history: code talkers from many Native American tribes. While the Navajo were well-known, over 30 other groups were not.

“I stumbled upon it myself,” Meadows said.

He was interviewing a Comanche World War II veteran, then in his 70s, when the man mentioned he served as a code talker.

“With the reality of mortality, I knew they wouldn’t be around to share their stories much longer,” Meadows said. “I dug in immediately interviewing all of the guys.”

As part of an ethnographic field school, students interview Vanessa Jennings of the Kiowa tribe.

This tenacity to uncover more and the humility to pivot directions to preserve important cultural experiences earned Meadows respect from many tribes, according to Vanessa Jennings. She is a Kiowa U.S. National Heritage Fellow.

“It is amazing to watch him record and document ancient information from these elders,” Jennings said. “Each bit is more information for the unborn generations to learn of our beautiful Kiowa culture.”

Dr. Bill Meadows takes his students to museums and memorials that honor Native Americans.

Congressional recognition

Much of what the general public knows about the code talkers’ contributions to military action has only been exposed in the last 20 years. This coincides with Meadows’ publications and the production of the film “Wind Talkers.”

“A lot of them had blessing ceremonies done before they left. Some carried traditional medicines into combat. They’ve shared the songs that were sung for them.”

In fact, Meadows testified before Congress in 2004. This contributed to the passage of the 2008 Native American Code Talkers Act. This act awarded congressional medals for all code talkers of both world wars.

Lobbyists distributed Meadows’ books to senators and representatives to educate and persuade them to provide recognition for other tribes. After hearing sufficient evidence, Congress can honor other groups in the future under the same act.

“The code talkers never went looking for this recognition,” it was their tribes, relatives, scholars and others, Meadows said.

After recently completing a book on WW I code talkers, he is working on a WW II volume.

With his deep roots in these tribal communities, he continues to receive tips. He hopes to identify and facilitate recognition for all tribes that participated – to make sure they are not obscured from history.

Decoding code talking

“Code talking allowed you to provide commands and plans on the open airwaves,” Meadows said. “Anybody could listen to it. But it was pretty much unbreakable.”

The languages were largely unknown, not written down and non-European based, he added.

Code talking entailed sending military communications in native languages. Some tribes also developed extensive coded vocabularies of newly formed words for military subjects, like tanks and artillery. At other times, they translated native words as alphabets to spell out proper names.

No matter which process was used, it saved hours of encoding and decoding. And in war time, hours saved lives.

None of the Native American codes were ever broken.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The Native American experience

Meadows evaluates more than how the tribes communicated. He also explores the ceremonies, myths, stereotypes and racism they experienced.

One of the most common myths was that all code talkers were sworn to secrecy. While the Navajo were, Meadows says dozens of newspaper articles widely shared information about other groups.

“I’m a collector and facilitator of information.”

Many today believe the code talkers weren’t U.S. citizens when they volunteered or were drafted in WW I. However, Meadows discovered that about two-thirds were.

He’s also been able to dispel the myth that all Native Americans in the world wars served as code talkers. Instead, they filled many ranks. Unfortunately, many had to confront the stereotype of the “super scout.”

“They were put in very dangerous positions and often told to take the lead. It was assumed they could run without making a sound and see better at night,” he said.

Fighting stereotypes

In the Pacific Theater of World War II, code talkers were treated well and even admired in their units. However, some were mistaken as Japanese and captured by other U.S. troops when not with white soldiers.

“Without the internet, travel and cultural awareness we have today, American Indians, Chinese, Korean, Filipino and even some Hispanics were confused as Japanese.” In the Pacific during WW II, “almost anybody that didn’t look European was confused as Japanese,” Meadows said.

All were eventually identified and released. Some had bodyguards assigned to prevent misidentification.

Dr. Bill Meadows overlooks a student field trip learning about Native Americans.

Relationships and recognition

“Dr. Meadows has provided both the Indian and non-Indian worlds with a small piece of written history that was only known through oral stories,” Lanny Asepermy said.

Asepermy is Comanche, a retired Master-Sergeant of the U.S. Army and Vietnam veteran. He has known Meadows for 20 years.

Meadows feels gratified that his books, along with the Native American Code Talker Act, will ensure Native American veterans will be remembered.

For him, the relationships and the cultural recognition make the job as worthwhile as the day he started.

“The Comanches gave me a Pendleton (Grateful Nation) blanket, which has stripes of all the military campaigns,” he said. “They said, ‘We have never given one of these blankets to a non-veteran. You’re the first and you’ll probably be the only one.’”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Finding faith in college

He believes that perspective ignores the attention to the sacred and spiritual on campuses. It also doesn’t account for the intersectionality of religious studies. It overlaps with many other disciplines – from social work to politics.

The role of religion in higher education is a dynamic topic right now, he noted. But as a sociologist, he’s always been intrigued by how religion fits into the context of human society.

Attention on religion

In 2001, he and Dr. Kathleen Mahoney ventured into an extensive research project.

“We wanted to test our hypothesis that there is more attention to religion now than at any time since the post-World War II era,” he said.

They began collecting data and historical documents from all available sources. Then they conducted in-depth research to fill in the gaps.

Finally, in 2018, they published “The Resilience of Religion in American Higher Education.”

“It’s a sustained look at how religion has survived and persisted on college campuses despite a multitude of changes,” Schmalzbauer said.

It is Schmalzbauer’s second book in a career that has produced more than 60 articles, book chapters and reviews – all in the same “intellectual neighborhood.”

“John is so creative. He does not take what he’s experiencing for granted,” Dr. Elaine Howard Ecklund said. She is the director of the Religion and Public Life Program at Rice University. “He’s able to step aside from the institution of higher education, even though he’s part of it, and shine a scholarly light on the way religion shows up in unconventional ways in higher education.”

Moving mountains

For the book, Schmalzbauer and Mahoney, formerly of Boston College, researched the history of religiously-affiliated institutions. They performed surveys, interviews and site visits. One primary question kept popping up: Are these institutions less committed and connected to their religious identities than in the past?

“There’s more religion than meets the eye on any campus.”

Schmalzbauer said the answer was a resounding no. In fact, many administrators reported feeling more invested in this identity. Others described trying to find new ways to stress this mission, even if there were fewer figureheads, such as priests and nuns.

“We realized this story is so much bigger than religious colleges. It involved schools that have no ties to a church,” he said. “We underestimated the Herculean task of pulling this together.”

One part of Dr. John Schmalzbauer’s research is looking at the changing landscape of religion over time – especially on college campuses.

They investigated nonreligious public and private institutions. By reviewing curricula and research in many areas of study, they found overlap throughout the humanities, social sciences, health care and law. The intersection of these subjects further proved that religion provides context in diverse discussions.

“Religion has always been in dialogue with other ways of seeing the world on American campuses,” he said.

The increased presence of religion at universities, he noted, is due to the combination of those who see it as an object of study and people of faith.

“Education doesn’t erode your commitment to organized religion or to a spiritual quest; it may heighten it.”

Documenting the student faith groups and ministries, he gathered the number of groups as well as the membership. He tracked the numbers over many years, trying to be inclusive of not only the most well-established groups, but also the newer ones with more regional or local affiliations.

As time passed during data collection for the book, the numbers continued to change. Organizations changed names. Some vanished. New ones appeared.

With the arrival of new religious groups or as students begin identifying as spiritual or skeptical, the landscape shifted.

“John works through the history of religion in higher education and talks about the ways in which it waxes and wanes,” Ecklund said. “It’s the best of history, religion and sociology. And he reveals that religion is experiencing a real resurgence.”

But Schmalzbauer says, it’s also a snapshot in time.

“It’s too easy for people to say, ‘higher education destroys religion,’” he said. “The real story is much more complex.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Examining the Kurdish question from a historical lens

The late scientist Dr. Carl Sagan said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.”

This is especially true when it comes to understanding tensions in the Middle East.

Historian Dr. Djene Bajalan offers insights into the Middle East by exploring the region’s history. He focuses on issues related to nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

An assistant professor of history at Missouri State University, Bajalan’s main research area is on the region’s Kurdish community. In particular, he studies how Kurdish political activism developed within the Ottoman Empire before World War I.

To date, Bajalan, who has taught in Iraq and Turkey, has published more than 20 journal articles and book chapters, and a book about Kurdish history.

To people trying to learn history in America, it’s important to understand dynamics around the world so we can draw lessons from other places and make comparisons.

Why are the Kurds stateless?

The Kurds are the world’s largest stateless nation. They live across four countries – Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. They are the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East.

One of Bajalan’s latest articles is on the question of Kurdish statehood. It examines why the Kurds failed to secure a nation state after the Ottoman Empire collapsed post-World War I. The piece argues that while it seemed like the Kurds had a good opportunity for independence at the time, in reality, they did not.

One of the points I try to make is often what we see is the people who become nationalist it’s because of their experience; it’s not necessarily because they have a separate ethnic identity.

Bajalan claims the main reason was that the Russian Revolution in 1917 changed the geopolitical situation in the Middle East. The Russians’ withdrawal from the area where the Kurds lived allowed the Ottomans to reoccupy much of the Kurdish homeland in 1918.

“The loss of Russian patronage and protection was a major blow to the Kurdish independence movement,” he said.

Turning a thesis into a book

Bajalan is now working on his monograph. He hopes to complete it in 2020. The monograph is an extension of his PhD thesis on Ottoman history from 1839-1914.

The thesis covered the beginning of Tanzimat, a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire. It continued until the outbreak of World War I. Bajalan wants to add a final chapter. It will feature the rest of Ottoman history from 1914-1923, including the empire’s breakup.

Dr. Djene Bajalan has published more than 20 journal articles and book chapters, and a book about Kurdish history.

“This monograph is a broader study examining the rise of the Kurdish question. More specifically, it explores the rise of the Kurdish movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire,” he said.

Middle East political scientist Dr. David Romano says Bajalan’s historical work is vital.

“When we look at something as complex as human choices within a political system, there’s an important element conditioned by people’s historical memory and culture. These things develop over time,” said Romano, the Thomas G. Strong professor of Middle East politics at Missouri State. “Professor Bajalan’s critical research helps us understand the context people are coming from better.”

Adding to the body of knowledge

For Bajalan, his interest to study the Kurds stems from two things. First, his father is Kurdish. Second, he wants to address the lack of research about the Kurds.

I challenge the simplistic way that nationalism and the growth of nationalist movements are often looked at.

Before the 1990s, there were very few books on Kurdish history in the English language. There were even fewer books on the Kurds and Ottoman Empire.

“For a long time, this has been a neglected area of study in the Middle Eastern studies field,” Bajalan said.

He attributes the neglect to the political nature of the Kurdish question in the Middle East and the limited access to information. It is also because the Kurds do not have their own nation state.

Historian Dr. Djene Bajalan offers insights into the Middle East by exploring the region’s history.

“I’m part of a new wave of scholars studying various areas of Kurdish history,” Bajalan said. “One of the most exciting things about my research is every single document I come across is something no one’s written about. Even if people have seen it, they’ve not included it in their work.”

Through his research, Bajalan aims to highlight how and why identity and politics intersect.

“I want people to understand the complexities of identity and politics, and why some groups orient toward politics based around identity,” he said. “It’s not an arbitrary thing – it’s for historical reasons.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Unveiling the mysteries of the Catholic Church

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman, associate professor of sociology, studies organizational leadership. For much of her career, she has focused on religious organizations, but she doesn’t want to be typecast. She wants to branch out to research nonprofit organizations and leadership more broadly.

But the controversies and the questions brought forth by the church bring her back.

She is a Catholic nun. One of the ways she gives back to the church is to add to the knowledge base of Catholicism. She’s partnered on six publications with several more in progress. She’s presented more than 40 times on topics like the intersection of moral issues and political mobilization in a congregation, and leadership in nonprofit and religious organizations.

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman meets with student Erica Houston in her office in Strong Hall.

In January 2019, “Catholic Bishops in the United States: Church Leadership in the Third Millennium,” was published. This book was a collaboration between Hoegeman and Drs. Stephen Fichter, Thomas Gaunt and Paul Perl from the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate.

I sort through the data and see what emerges and what’s interesting.

The team reached out to survey more than 400 bishops in the U.S. They were pleased by a 70% response rate.

Being a bishop

With this robust survey response, they developed a narrative. This book serves as a unique and comprehensive view of life as a bishop.

It addresses the demographic makeup of bishops. It also answers questions about daily routines, job satisfaction, leadership style and opinions on hot topics.

In her previous research, Hoegeman explored whether bishops’ liberal or conservative theological orientation influenced decision making. For example, would the bishop use lay people to lead parishes in the absences of priests? Hoegeman found that liberal bishops were more lenient on issues like this. However, the terms conservative and liberal don’t follow traditional political party lines.

“You can’t vote Catholic along party lines,” Hoegeman said. “Catholic teachings are morally conservative and socially progressive.” She ticks off the hot button issues and sympathetic causes for Catholics. “It’s very complex.”

Dissecting the diocese

Her next project, a book unveiling the intricacies of the diocese, will have similarly rich data. And Dr. Gary Adler, a colleague from Pennsylvania State University, appreciates her commitment to diving deep into the data to tell the story.

“Katie connects theoretical ideas and sophisticated methods to her research,” Adler said. “This willingness of hers to fully embody the profession, no matter the circumstance, is a gift.”

She’s mined information that was collected regularly during the last 40 years. One of the primary concerns for her is whether the Catholic Church can be dynamic enough to meet the changing needs of its followers.

Katie’s research on numerous dimensions of congregations — from gender, to social activism, to vitality — has significantly contributed to the field. – Dr. Gary Adler

The greatest concentration of Catholics in the U.S. has historically been split between the Northeast and Midwest. Each area accounted for about 35% of the Catholic population. In the last five to 10 years, greater numbers are showing up in the South and West.

In a religion with less organizational hierarchy, churches would begin popping up. But the Catholic Church, notes Hoegeman, has less agility because of the structure and personnel involved.

You can say, ‘I have my own religion.’ But from a sociological perspective, it’s a group phenomenon.

“What you get are these small, empty parishes in the Northeast and places like Las Vegas – with a booming population – with relatively few, huge parishes,” she said.

Upon closer examination, some of the diocese within New York are still growing exponentially. Why?

“I’m going from the ground up to look at this shift. Part of the story is about immigration and part is related to organizational decline,’” like the closings of Catholic parishes, hospitals and schools, she said.

It will come down to organizational leadership, something Hoegeman knows a lot about, to weather these changes.

A nun’s mission

As she delves into her research or heads into work, the mission of her community of Sisters is never far from her mind.

“My order’s particular emphasis is uniting people, looking for people at the margins,” she said.

To this end, she spends hours with struggling students, making herself available.

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman strolls the office corridor with student Veronica Jacobs.

“My purpose is to bring unity and to level the field. I believe through mentorship, I’m making myself and education accessible.”

And with her research, she is bringing greater understanding to the church she is committed to.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Blending history, pubs and politics

That’s the reality today.

But in the 19th and early 20th centuries, public houses (nicknamed pubs) didn’t offer food.

You may think it changed in order to turn greater profits. Instead, Dr. David Gutzke argues that pubs evolved in Great Britain as a ripple from the Progressive movement. He believes his greatest scholarly contribution is that he established the Progressive movement as a transcontinental movement. Previously, it was considered as American as apple pie.

Gutzke, a distinguished professor of history at Missouri State University, set the stage in his book, “Pubs and Progressives.” He focused on the period between World War I and World War II. Historically, it is known as the interwar period.

I don’t want to write the same type of book that somebody else might do.

As a professor of British history, an international scholar on the topic of alcohol use and a historian looking at social change, he has published more than 20 books and articles on these subjects. “Pubs and Progressives” nicely knits these interests together.

If you build it, they will come

“The brewers were trying to change the type of people you expected to see in pubs. They wanted middle-class people as customers. Brewers wanted respectability,” he says, “both for themselves and public houses.”

This aligned with the Progressive movement’s values. Progressives wanted to right social ills. They desired efficiency, discipline and order. And they sought government intervention to improve society.

You have to understand the past on its own terms.

One brewer Gutzke studied, Sydney Neville, wrote in his memoir he felt personally responsible to the general public to discourage drunkenness.

“The slogan of the whole movement was, ‘We do not want people to drink more beer. We want more people to drink beer.’ I thought it was very clever,” Gutzke said.

One way to attract a different clientele: Brewers spent tens of thousands of pounds beautifying spaces, adding courtyards, gardens, linen tablecloths and fresh flowers.

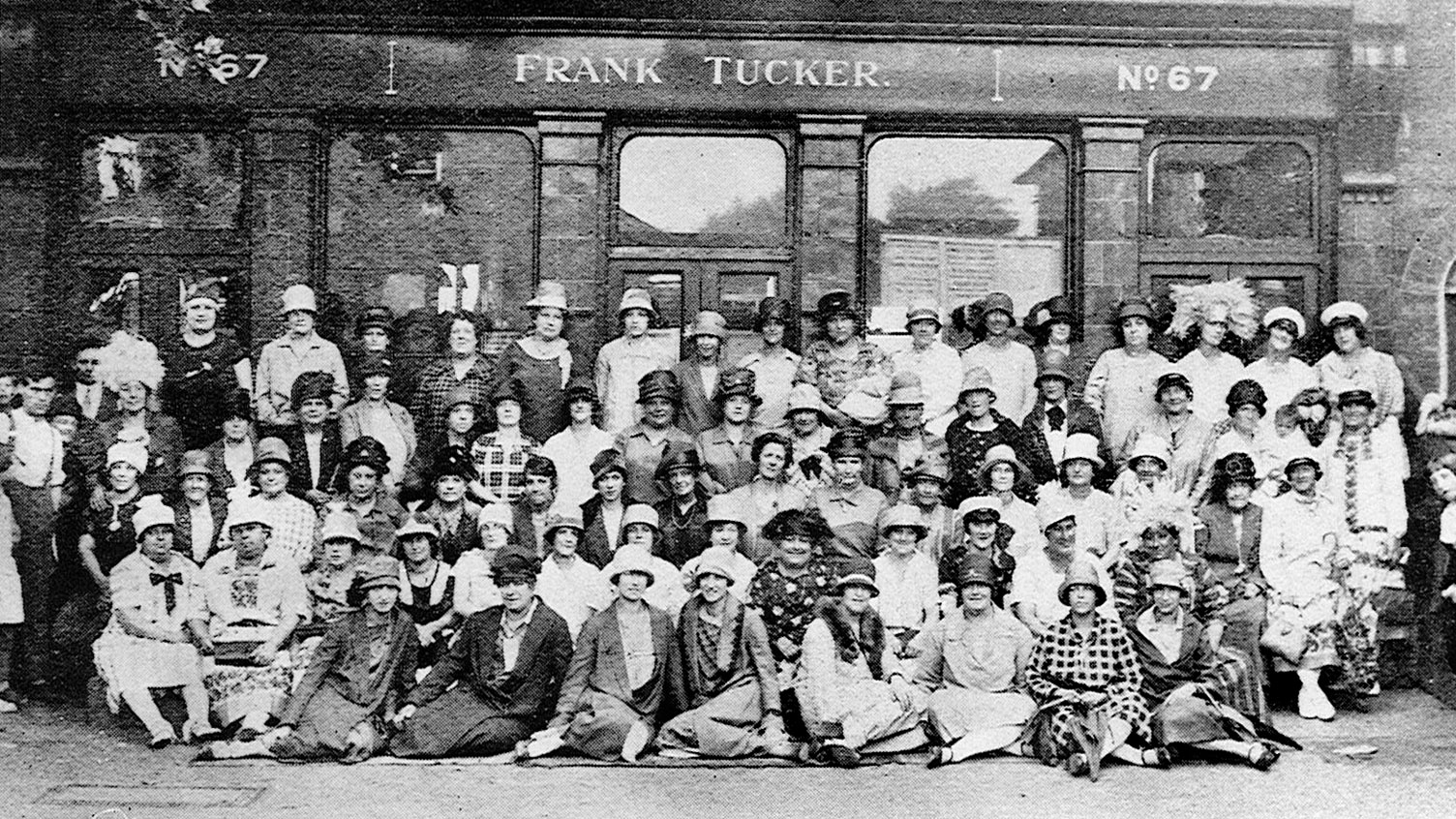

In an attempt to draw in more women or upscale clientele, brewers redecorated and expanded their offerings. Photo submitted by Dr. David Gutzke

“Before the first World War, the pub was a masculine republic. Progressive brewers were very keen to bring women in,” Gutzke said. “They believed women could act as a restraint on drunkenness.”

Money hungry?

Then brewers expanded into offering a full menu. Food made the pub seem like a respectable place to spend time and eat dinner as a family.

You must not allow present-minded concerns to be projected into the past.

Large Progressive brewers, like Neville, recognized building new, expensive pubs would likely eliminate smaller, “less scrupulous competitors,” who tolerated drunkeness to maximize profit. This statement alone says Progressive brewers desired profitability, but not at the expense of moderate drinking. More importantly, notes Gutzke, it reveals a desire for social change.

“Neville writes in the preface of his book, ‘I just hope that people come to understand what we were doing after I’m dead,’” Gutzke said.

Finding the evidence

Digging into publications from political scientists, anthropologists and sociologists, Gutzke drew a more robust world picture. This comparative history helped him identify the Progressive movement in Britain.

I like the way they frame questions differently. I like to think in those terms.

Gutzke also gathered photos, ledgers and legal documents to see the buildings before and after renovations, as well as changes in sales over time. For “Pubs and Progressives,” he gathered data from about 6,000 pubs.

“He is a master researcher who ferreted out all sorts of records that are difficult to locate,” said Dr. William Rorabaugh, a colleague from University of Washington. “He interviewed a significant number of leaders in the alcohol industry – an industry which is perhaps understandably ordinarily very tight-lipped.”

The proprietors of The Man of the World drew this large group of women to the pub in October 1928. Photo submitted by Dr. David Gutzke

British mystery novels from the interwar period also proved insightful.

“In a roundabout way, novels that aren’t trying to be historical documents can accurately depict the general public’s perception of life,” Gutzke said.

The general public, he says, thinks historians write history books to get everything factually correct for future generations.

“The truth is an abstract concept,” Gutzke added. “Historians engage in how to understand the past.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Historical images provided by Dr. David Gutzke

Further reading

Ozarks history through a realistic lens

But Dr. Brooks Blevins, the Noel Boyd professor of Ozarks studies, works to change these misconceptions through his research. He pores over countless materials about the Ozarks and conducts oral histories to provide a truer picture of the area and the people who live here.

A lifelong Ozarker, Blevins grew up on his family farm in rural Arkansas. He always loved history. When he got interested in the Ozarks as a college student, he chose to study both and devote himself to research.

“Since I lived here, this topic was much more personal to me,” Blevins said. “I noticed there wasn’t much good history of this region. A lot of the writings were influenced by folklore and travel writers. They tended to be romantic and unrealistic.”

Map of the Ozarks. Map by Emilie Burke, maps and GIS student assistant, Missouri State University

What is the Ozarks?

The physical Ozarks is roughly 40,000-45,000 square miles. It covers much of the southern half of Missouri and a large part of northern Arkansas. It also extends into northeast Oklahoma and southeast Kansas.

While the physical Ozarks is well defined, its cultural boundaries are less so, Blevins notes. This is because people may live in the region, but do not identify as Ozarkers.

The first in a trilogy

Blevins has spent more than two decades discovering the Ozarks’ rich history. He has authored eight books, two of which are award winners.

His latest book – “A History of the Ozarks, Volume 1: The Old Ozarks” – came out in summer 2018. It’s the first volume in a trilogy that offers a comprehensive history of the region. No other book like this exists.

“I noticed there wasn’t much good history of this region. A lot of the writings were influenced by folklore and travel writers. They tended to be romantic and unrealistic.”

Volume one highlights the early days of the Ozarks before the Civil War. It chronicles the area’s formation and the lives of Native Americans. It also documents European colonialism and the mass migration of settlers.

Blevins writes about people as they hunted, fished, founded schools and churches, and developed communities. He tells colorful human stories within the context of what was going on in American history at the time.

Blevins says the most surprising discovery during his research was the central role “immigrant Indians” played in the old Ozarks. These displaced natives from east of the Mississippi River came from different tribes.

“For about two generations, thousands of them lived in the region. In the 1820s, they even attempted to establish a sort of autonomous Indian nation in the Ozarks,” Blevins said.

Gary Kremer, executive director of The State Historical Society of Missouri, has read Blevins’ book. He says the breadth and depth of his research is outstanding.

“This book will enhance people’s understanding of the Ozarks because he brilliantly narrates the many ways in which the land and the people of the Ozarks interacted to shape each other,” Kremer added.

The Jacob Wolf House in Norfolk, Arkansas, served as the first permanent courthouse in Izard County. Photo by Bob Linder

A sneak peek

Blevins is working on volumes two and three of his trilogy. The target publication dates are summer 2019 and 2021, respectively.

Volume two will focus on the long Civil War and Reconstruction era. Its main topics include slavery in the Ozarks, the secession crisis, the resulting war and the region’s reconstruction. It will also introduce the idea of the cultural Ozarks.

The third volume will pick up the story at the end of the 19th century into the 21st century. It will include a wide array of topics, from farming and industry to music and tourism.

“Underlying almost all the books’ subjects is an ongoing exploration of the perpetuation of cultural stereotypes and the role that the region’s image has played on its history and development,” Blevins said.

A large crowd gathered as Dr. Brooks Blevins shared about Ozarks history and explorer Henry Schoolcraft in September 2018. Photo by Bob Linder

Relating to the masses

While Blevins is an academic, he tries to write history books that connect with common folks. He wants people in the Ozarks to know they have a valuable regional history of their own and take pride in it.

“It’s often a warts-and-all story like the American experience in general,” Blevins said. “But there are many interesting and iconic people and things that had their origins right here in the Ozarks.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Main photo by Bob Linder

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Risky business: The future of football in the United States

If you said yes, Dr. Pam Sailors encourages you to reconsider.

“Kids start playing football as soon as their little necks can support the helmets on top of their heads,” Sailors said. “By the time they are old enough to make the choice to play, a lot of the damage has already been done.”

Professional and college football is one of the most-watched dramas in the U.S., but it’s become known as a risky activity.

“I’m torn about this. It’s kind of like ignorance is bliss in many ways. It’s hard for me not to watch football, but I feel kind of scuzzy about it if I do because it’s like watching people in a fight club or something. Because you know they’re hurting one another and you’re taking some sort of pleasure in it.” — Dr. Pam Sailors

Sailors, associate dean of the College of Humanities and Public Affairs, focuses her research on philosophy of sport. She reviews previously published pieces, then adds her own ideas to the discussion.

She’s written more than 60 papers, presented at about 50 conferences and appeared as an expert source in more than a dozen media publications.

Sailors published Personal Foul: An Evaluation of the Moral Status of Football in 2015. The paper was the first to use philosophical argument to challenge the ethical acceptability of football, both amateur and professional.

“Pam’s research is novel and makes not only an important contribution to the literature, but is also applicable to real-life scenarios,” said Dr. Charlene Weaving, an associate professor at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia. “She has an ability to make ethics come alive.”

Players pay the price later in life

Dr. Pamela Sailors contributed a chapter, entitled Borderline Cases: Crossfit, Tough Mudder and Spartan Race, to this 2016 book, “Defining Sport: Conceptions and Borderlines.”

Playing football is ethically problematic for three reasons, Sailors said: the likelihood of brain damage, objectification of players and a culture that entitles players to free passes for some social offenses.

When it comes to the likelihood of suffering brain damage, Sailors specifically referenced chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, or brain deformation caused by repeated subconcussive blows to the head.

“We know now that smoking causes health problems. We don’t let kids do it,” she said. “We don’t even say, ‘We’ll just let them smoke a little bit until they’re 18, and then they can choose.’”

Sailors cited one National Football League, or NFL, survey that showed almost half of retirees said they suffered from severe pain as a result of playing. The game’s head injury risk could affect its popularity.

“We still have boxing, but it’s not as popular as it once was,” she said. “I think football may be on a similar track unless there are some radical changes. The changes might be so radical that we wouldn’t even think it was football anymore.”

Why make millions when others make billions?

Football players should be paid appropriately for taking on those health risks, Sailors said, but that isn’t happening in the NFL or university teams. She cited a 2013 report which stated the top 10 NCAA football programs banked more than million and did not pay their athletes.

“I know professional football players make what seems like a lot of money, but compared to what the owners make, and the number of years they make it, they don’t,” Sailors said.

“College players are not supposed to make money. I think there’s just a huge profit being made on the backs of people who are the ones who are having the bad health consequences, but they’re not getting their fair share of the profits.”

A culture of acceptance, no matter the offense

Finally, there’s the issue of players seemingly getting free passes for bad behavior off the field. Sailors described it as a problem with football culture, exemplified most recently by Oklahoma running back Joe Mixon.

He was a first-round draft talent whose stock fell after video surfaced of him hitting a woman in a restaurant. The Cincinnati Bengals still drafted Mixon in the second round and will give him an opportunity anyway.

Sailors noted in “Personal Foul” that a culture of violence and “idealized masculinity” contributes to such behavior, especially against women.

These issues are not unique to football, she said. But here’s what is.

“Other sports have brain injury trauma problems, take advantage of players for profit and have a culture of entitlement,” Sailors said. “But what makes football unique is it’s got all three.”

The next step in Sailors’ project is determining what this means for spectators and fans of the game.

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Main photo by Bob Linder

Further reading

Keeping parolees out of jail

Dr. Brett Garland, head of the department of criminology and criminal justice at Missouri State University, has been studying the criminal justice system for over a dozen years. He’s published more than 40 journal articles, book chapters and other scholarly works, mostly on topics pertaining to correctional issues.

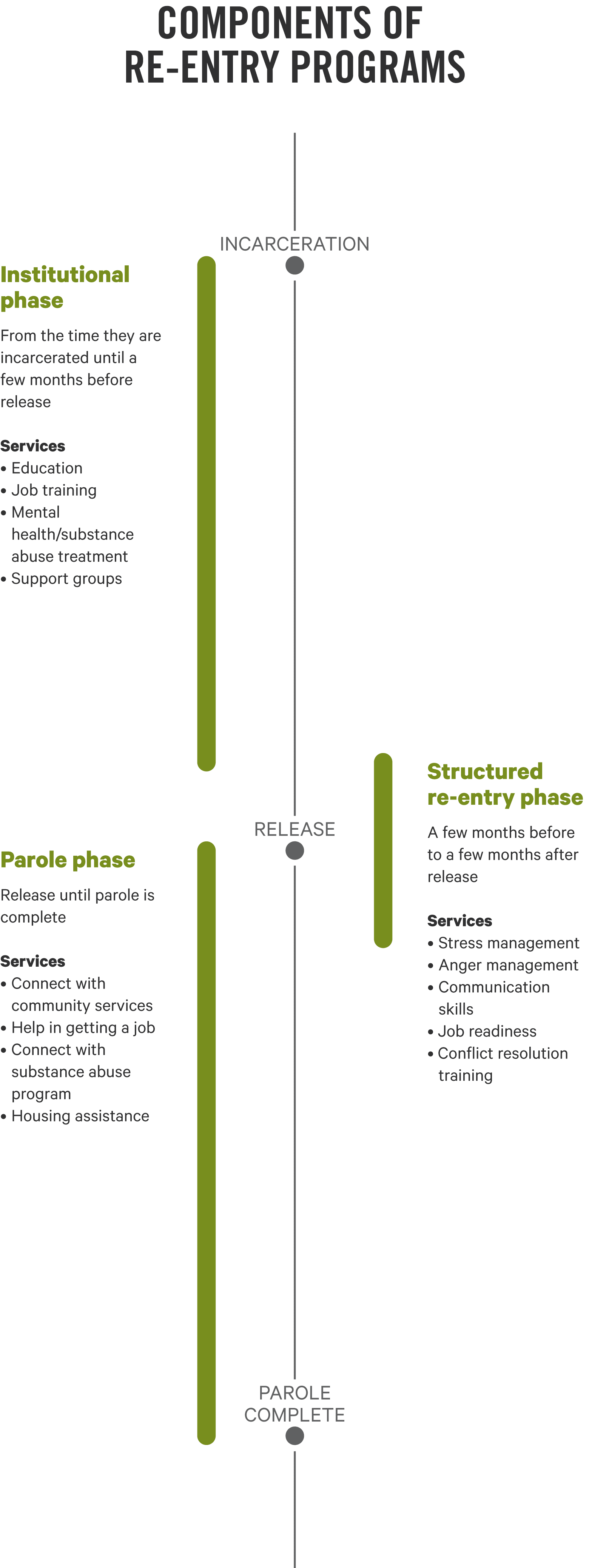

One primary area of research for Garland is prisoner re-entry. That’s the phase from a few months before a prisoner is released to a few months after release.

“That’s the time period where offenders are really starting to transition mentally; they’re getting themselves ready for the release,” he said.

Which is better? The carrot or the stick?

A study Garland did with co-authors Dr. Eric Wodahl and Dr. Scott Culhane from the University of Wyoming and Dr. William McCarty from the University of Illinois at Chicago found that offenders are most successful in following the terms of their parole when a combination of sanctions and rewards are used.

“We know from psychology and from behavioral learning theory that rewarding people for things they do right is even more important than punishing people for something they do wrong. Our study confirmed that this principle holds true for criminal offenders,” said Garland. “In the last decade or so, there’s been renewed attention to incorporating incentives and using a true behavioral model when monitoring people who are on probation and parole.”

Garland has collaborated with Wodahl on a number of projects. Wodahl is a former probation and parole officer and said he thinks this research can help supervision officers do their jobs more effectively.

“I believe this research has the capacity to help lessen our reliance on prison in this country,” he said. “A large portion of prison inmates are incarcerated for violating the conditions of their probation or parole supervision. The use of sanctions and incentives has been shown to lead to fewer revocations and fewer people being sentenced to prison.”

Garland said to gain maximum compliance from a probationer or a parolee, officers must be committed to utilizing reinforcements whenever suitable opportunities arise.

Time off is best incentive

Another study by Garland and Wodahl, in Colorado, examined the value that offenders ascribe to various types of incentives relevant to probation.

The researchers interviewed 200 offenders and presented 16 options, including monetary incentives, reductions in supervision time and travel opportunities, among others.

“The perceived effect from the offender’s standpoint was that getting time off of a sentence was more important to them and therefore more valuable than all other options,” said Garland. “The policy implication here is that you don’t necessarily have to spend a lot of money to provide good incentives for offenders.”

As the cost to incarcerate a person continues to increase, finding ways to keep people out of prison may be the best solution. Garland hopes his work will help do just that.

- Story by Andrea Mostyn

- Photo by Kevin White

Further reading

Developing cultural competence in tomorrow’s leaders

“Post-millennial generations are going to be incredibly visually oriented,” he said. “If we don’t captivate their interest with this type of a digital humanities project, the humanities are going to fade away into being insignificant in the public’s mindset.”

“Post-millennial generations are going to be incredibly visually oriented,” he said. “If we don’t captivate their interest with this type of a digital humanities project, the humanities are going to fade away into being insignificant in the public’s mindset.”

That’s why Chuchiak, professor of history and director of the Honors College, and Missouri State alumnus Justin Duncan are creating the Digital Auto-de-Fé, a 3-D simulated recreation of the 1601 Public General Auto-de-Fé of the Mexican Inquisition.

The project will attempt to visually and interactively portray the human experiences, pains, shame and public punishments related to these acts of religious intolerance that occurred hundreds of years ago in multiple places around the globe.

The project uses video game technology for a greater purpose: cultivating cultural competence in middle school, high school and college students in the modern age.

“We created a virtual reality simulation of the inquisition’s auto-de-fé, through the story of a young Jewish woman who was persecuted by the Mexican Inquisition, to teach empathy and religious tolerance,” Chuchiak said. “Using an avatar as either a viewer or participant in the event, you’ll feel the terror of being persecuted.”

“You’re going to see what it’s like to be a member of a restricted caste or class. That’s part of our goal: to teach empathy and racial and religious tolerance.”

The inquisition in Mexico is among Chuchiak’s main areas of study, which also include research into the Spanish military conquests against the Maya, and the study of the role of the Maya in Spanish colonial defense against European piracy.

Chuchiak’s accomplishments include four published books, two published translations of primary sources in translation, 50 published book chapters or journal articles and more than 100 international and national conference paper presentations and keynote invited lectures.

What’s an auto-de-fé?

The public “act of faith,” or auto-de-fé, was a costly public spectacle mandatorily attended by all residents of a major city. The Inquisition intended these spectacles to serve as major educational tools and deterrents to religious dissent.

The people of Mexico were required to fall in line with the teachings of the Catholic church. If they didn’t, they’d be fortunate to bear the public shame of appearing in a public auto-de-fé. The other options were far more grisly punishments for those convicted of false belief, up to and including a death sentence.

You’re going to feel it

“It’s easy to read about points in history, but when people begin to see and feel an event, history and humanities in general come alive,” said Duncan, a special education teacher at Springfield Public Schools.

The idea for this digital humanities project came to Duncan while writing his graduate thesis – under Chuchiak’s direction – of the Spanish Inquisition’s autos-de-fé of that time period. He had a difficult time explaining what the space and concepts of power involved in these events looked like in words.

Users can live the story of a young Jewish woman, Mariana Núñez de Carvajal, who watched her parents get burned alive for practicing Judaism after being forcibly converted to Catholicism. She was later burned at the stake by order of the Mexican Inquisition for the same transgression.

It’s the chance to live in a virtual world as a member of an oppressed class, a middle class, and even those in positions of power – tens of thousands more characters will be developed as options for future viewers – that will drive the point home to students.

Users will experience the sights and sounds of the terrifying event of an Inquisitorial auto-de-fé with sensory vibrations. Scornful public observers throw items at the oppressed characters, who walk dressed in the ceremonial garments of shame, known as the Sanbenitos, that the inquisitors forced them to wear.

What lies ahead

The project team includes 15 members, featuring top subject area experts from universities from the U.S. and Mexico. The group includes Missouri State faculty Vonda Yarberry and Colby Jennings, who serve as electronic arts consultants and advisers.

Digital Auto-de-Fé has expanded to the grants stage, which includes applying for funding through the National Endowment of the Humanities, National Endowment of the Arts and private foundations in the U.S. and Mexico. Just to get started, Chuchiak said, the cost will be about $300,000.

Still, the payoff could be huge.

“Students are going to see how ugly it was when religious intolerance is in play,” Chuchiak said. “We’re at the cusp of a change in the way humanities are going to be taught, and this is part of it. People should know that everyone’s views, religions and cultures are worthy of respect.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

History and memory: Making peace after religious conflict

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Throughout the better part of the next three decades, Protestants engaged in iconoclasm, or the destruction of religious images and relics, as they believed their reverence was a form of idolatry. In the process, they demolished a multitude of sites and artifacts sacred to Catholics.

But what happens after the dust settles?

“My real interest isn’t in the smashing of the relics. I think that story is pretty straightforward,” said Dr. Eric Nelson, professor of history at Missouri State University. “It’s what you do after something like that happens. I think that’s where the story can unlock a whole new set of ideas.”

History and memory, according to Nelson, are two very different ways of remembering the past. While the history of these battles illuminates the divide between Catholics and Protestants, the memory of what happened has the ability to reconcile differences between the two sides.

How does this happen? This is Nelson’s primary research question and has been at the root of his recently published monograph “The Legacy of Iconoclasm: Religious War and the Relic Landscape of Tours, Blois and Vendôme 1550-1750.”

“Once blood is shed over religious ideas, it’s very difficult to make peace,” said Nelson. “I’m interested in peacemaking after violent religious conflicts.”

Pillaged and plundered

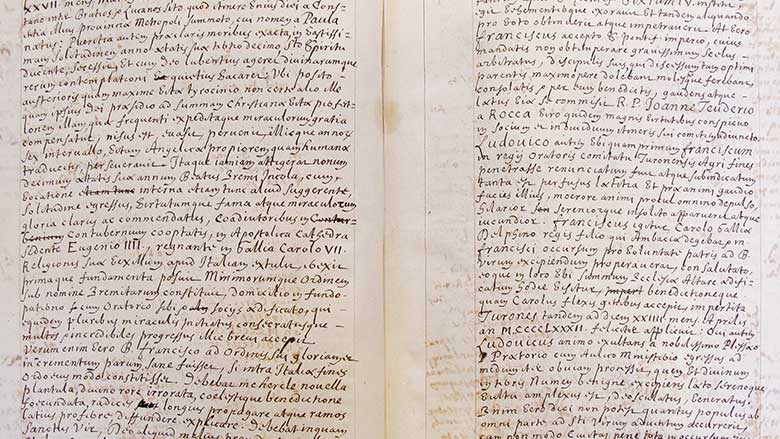

Saint Francis of Paola, born around 1416, was the founder of the Minims, a Roman Catholic order of friars.

Francis, a renowned healer and miracle worker, spent much of his later life in Tours, France, where a Minim monastery would eventually be built. Francis died in 1507 and was later canonized by Leo X in 1519.

On April 2, 1562, Protestant forces captured the city of Tours, and on April 7, they seized the Minim monastery. During the looting, troops forced open Francis’ tomb and cremated his remains, destroying the precious relics of the order’s founder.

While this account of the events of the day is truthful and factual, it is very different from the story that Nelson had come to know.

Submitted by Dr. Eric Nelson

A saint and a martyr

Nelson, who has studied European religious history for over a decade, discovered stark differences between what he thought happened and what actually happened by visiting sites of iconoclasm in Europe and diving deep into the archives of Tours and the Vatican.

“After going back to the documents in the actual archive, I realized almost nothing about the Minim version of the story is actually true,” said Nelson. “But the story they came up with was much better than what actually happened.”

In their account of the burning of Francis’ remains, Minim historians assert that Protestants failed in their effort to weaken devotions to the saint. Instead of a victory for the forces of evil, the burning of his body represented God’s good will and favor toward the saint, allowing him to rise to the title of “martyr.”

Evil men, as one Minim historian concluded, became “the instruments for the honor and glory of our Saint.”

Peace through memory

Submitted by Dr. Eric Nelson

As Nelson compared notes between the two accounts, he discovered a profound intersection between history, memory and peacemaking.

“Francis’ grave was desecrated — his bones were burnt and spread to the winds,” said Nelson. “If the Minim had to stick to what actually happened, it’d be much harder to make peace. Instead, they focus on a much more positive point of view.”

As a member of the international Sixteenth Century Studies Society, Nelson’s discoveries are helping reshape the narrative of early modern French and European history, according to Dr. Amanda Eurich, professor of history at Western Washington University.

“His imaginative insights allow us to recapture the spiritual worlds of the past,” said Eurich. “It reminds us that the religious violence and iconoclasm wars not only marked the physical landscape of France, but also cultural memory for generations.”

“People think of history as a series of events that happens that you memorize and then there’s a test and you’re done. In reality, history’s a living thing. It’s always evolving. Every generation writes its own history.” – Dr. Eric Nelson

According to Nelson, this reimagining of history is powerful: “What people think happened is sometimes far more important than what actually happened. The real reality is the story they constructed — that’s the power of memory in peace making.”

Knowing how history evolves and is shaped by memory is paramount to today’s society, because religious violence is with us for the foreseeable future.

“We know how to get into religious wars just fine — we can start them really easily,” said Nelson. “It’s how you get out and make peace afterwards — that’s where the real lesson is learned.”

- Story by Zachary Riel

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

An everyday life of Biblical proportions

“The house I grew up in and every school I went to was destroyed,” said Matthews. “Much of me went away in the sky, and yet I was able to go back down there and identify what was remaining of the structure that was my childhood home.”

Matthews took a picture of the ruins and uses it in class as a way of talking about how space is still present in our memories. This speaks to his area of expertise: the history and culture of the Biblical era. Though physical remains may be few, the everyday lives of the people from this time can be better understood by studying the stories and artifacts that they left behind.

‘What the devil are they doing?’

How do we learn more about the ancient world? This is one of Matthews’ research questions. He says it’s important to understand that we tend to filter everything through our modern scope.

“We are trying to find out what the devil they were doing. Unfortunately, this often means applying our modern viewpoint and totally skewing the whole thing.”

Biblical narratives, like most stories, assume that the audience shares a defined set of social understandings or customs. When we don’t know what these customs are, we must use several different methods to try to discover them.

“I have made good use of modern research and analytical methods in the social sciences —sociology, anthropology, psychology, communications — to evaluate the ‘human moments’ in the narratives,” said Matthews. “For example, when I examined the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38, I looked for the social cues in the story: clothing, marriage status, power relationships, gender, speech patterns and the physical placement of the characters.”

Matthews applied these methods when writing and researching his most recent publication, the fourth edition of “The Cultural World of the Bible: An Illustrated Guide to Manners and Customs.” It is one of 17 books he has authored, and he has published numerous articles on the subject as well.

Putting together a large puzzle

“When we say cultural world, what it basically says to people is that we’re going to talk about everyday life. What did they eat? What did they wear? How did they celebrate? What were their burial practices? What kind of weapons did they use?” he said. “All kinds of topics like that.”

There are several ways we can learn the answers to questions like these: written records, including the Biblical text and extrabiblical documents; physical remains such as tomb paintings and grave goods, garbage heaps, and the ruins of buildings, which are studied by archaeologists; and the study of both modern and ancient cultures via analogy.

“Reconstruction of the world of ancient Israel is like putting together a large puzzle,” said Matthews. “Some of what I included in the book came from my own travels in the Middle East, some from basic research and discussion with colleagues, and some from studying how other authors shaped their treatment of the subject.”

Talking about talking: analyzing conversations

Matthews, who has been a Biblical scholar for more than 30 years, has also recently focused on the conversations that occur in these Biblical narratives and what they can tell us about the characters and their daily lives.

“There is a lot of conversational analysis in communications, sociology, anthropology and psychology,” said Matthews. “I got interested in seeing how the different disciplines analyzed conversation, but, of course, what I’m working with is text. I have narratives with embedded dialogue.”

“It allowed me to develop a richer understanding about the setting of the story, the human drama associated with a childless widow, the importance of clothing as a social marker and the role that place—physical location—holds in determining how humans interact.” (Matthews on studying the human moments in narratives.)

Matthews studied the way these disciplines researched conversations, which mostly consisted of analyzing live conversations. He applied many of the techniques and concepts they used to the narratives he was studying and was able to discover previously unknown contexts. His book, “More Than Meets the Ear: Discovering the Hidden Contexts of Old Testament Conversations,” was published in 2008 and led to a journal article in 2014, “Choreographing Embedded Dialogue in Biblical Narratives.”

Matthews graduated from Missouri State in 1972 with a bachelor of arts degree in history, and received his masters and doctorate in Near Eastern and Judaic studies from Brandeis University in 1973 and 1977 respectively. He has spent most of his career focused on the historical aspects of religious studies, and looks forward to continuing his studies on ancient Biblical culture and writing about what daily life was like thousands of years ago.

- Story by Shay Stowell

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Eye to eye or eye for an eye

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

“The definition is always what others do to us. It’s always going to be a guy or group on the other side of the street,” he said.

Although approximately 50 such agitators or groups exist in West Africa, Oyeniyi has written and presented extensively on Boko Haram, which has garnered much attention from the media since it was assembled in the early 2000s. According to Oyeniyi, this group is easier to study than most since the founder Muhammed Yusuf recorded sermons and distributed them widely in the form of CDs, DVDs and leaflets in the early 2000s.

“There are people who will come out boldly to address the public in the form of open air preaching. What are they agitating for? Their belief system,” Oyeniyi stated.

The initial sermons are contraband now, but founding members of Boko Haram can serve as a lead for Oyeniyi. These ex-members offer insights into what drives the agitators to don the suicide vest. Moreover, these former members also could bridge the gap to begin peaceful negotiations.

As a social historian, Oyeniyi looks for patterns within the movements of specific groups and traces the roots of the conflict. Tracing the trends, he is able to build a profile of what an agitator group looks like and what the likely outcomes could be. He begins to postulate: What are they really fighting for? How are they getting their training? Who are their allies? Who funds them? Then, he and his collaborators create suggestions and form conclusions that the government can work with to address the root of the issue.

As much as possible, I want to see a world where we are all free. Free to express our anger against established institutions and individuals and also free to be corrected. So I long to see a Nigeria that is peaceful. I consider this my own way of contributing to it by exposing what is going on.

Greed versus grievance

Greed versus grievance

What he has to say might shock you. He understands Boko Haram’s complaints.

“They are requesting something, part of which includes the fact that the nation-state is, as it is, not properly governed,” said Oyeniyi. “So they have social grievances, and they have also what I call greed.”

Their grievances are at least, in part, related to a religious struggle as old as time. Two categories of Muslims abound in Nigeria: those who believe the Quran is not open to interpretation and want to see Sharia law enforced as the indisputable law of Nigeria; and those who see the Quran as open for interpretation and therefore welcome innovations, like Western education. In Nigeria, the second category is the majority.

If you eliminate Boko Haram today, you still have 49 other groups to deal with. It should not be about eliminating a group or set of groups, but looking at the causes.

One of the primary reasons behind the formation of the Boko Haram – which means Western education is a taboo – was the removal of innovations from Islam. Since the colonial period, there is no dearth of groups crusading against this, and these groups unite in their belief that other Muslims, especially those in power, are corrupt. Since 2000, Boko Haram has engaged in heated ideological and doctrinal debates with other Muslims, who found the group’s teachings unwelcoming to progress and sought state intervention to rein the group in.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

“The state itself needs to understand at what point human rights kick in. Boko Haram may be a terrorist group, but they also have fundamental rights that must be respected. We must recognize this if we’re going to fight and win against Boko Haram,” said Oyeniyi. “As things are, the government has failed to realize that dissatisfaction in the eyes of man will almost always force him to take radical actions.”

In summer 2015, Oyeniyi traveled to his homeland of Nigeria to collect documents Boko Haram released before they decided to go underground. Now, he will translate and make them available in the form of a book. By doing so, he hopes to gain further insight into what genuine concerns stand behind the rhetoric.