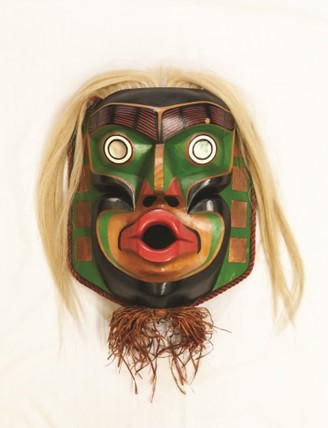

by Joe Peters, Jr.

Kwakiutl culture

20th century

Cedar wood, abalone shell, horse hair, pigments, and cordage,

L. 35 cm x W. 15 mm x H. 55 cm

Mace collection #TM148

The Dzonokwa Spirit Mask portrays a character Kwakiutl mythology that is known as “the wild woman of the woods,” a spirit that is believed to bring great power to chiefs. These masks are identifiable by several features, the most distinctive being its large, puckered lips; the Kwakiutl believe that the mouth is a link to one’s soul, and this spirit is believed to make an “oooh” calling sound. The masks are also made of cedar wood, which symbolizes the ritual transformation of the wearer into the identify of the spirit.

Dzonokwa masks are worn during summer celebrations and rituals known as Baxus, when potlatches are held, and also during the winter celebrations and rituals known as Tsetsequa, when supernatural energy that resides in Kwakiutl communities renders the Winter Ceremonials to be sacred. Researched by Rylee Williams

Iroquois culture

20th century

Cornhusks and raffia, L. 25 cm x W. 5 cm x H. 28 cm

Mace collection #TM176

Husk Face masks are created and worn by the men who are members of Iroquois masking societies known as the Society of Faces. The masks are one type of the False Face masks that are worn for ritual performances during the Midwinter Festival. During this festival, animal spirits and ancestral spirits are celebrated; because certain illnesses and physical problems are associated with the displeasure of these spirits, rituals are conducted to pacify and placate these spirits. The chief members of the Husk Faces act as the medical professionals, and they ritually sprinkle water on patients and conduct other rituals to cure their illnesses. This Husk Face mask is one of two False Face masks made of cornhusk cordage that act as door openers and that accompany the other False Face maskers during the Midwinter Festival. Researched by Rylee Williams

Desana culture (?)

20th century

Macaw feathers, basketry, and cordage,

L. 20 cm x W. 20 cm x H. 30 cm

Zinn collection #2014.5

This headdress is most likely the work of the Desana culture of Colombia, as its form and materials reflect the Desana creation myth. This myth states that, at the beginning of time, there were only two beings, the Sun Father and his younger brother, the Moon. Both of these beings wore crowns made up of the feathers of tropical birds that lit up the sky with color; the macaw is believed to be the bird of the Sun Father because its bright feathers shine like the rays of the sun through the rainforest canopy.

Although Desani women wear feathers as ear and body decorations, the macaw feather headdresses are almost always reserved for men, and they are worn during important social events and religious ceremonies. These headdresses do not indicate status or power, however, but stages of life. Young Desani boys typically wear intricate headdresses made of the colorful feathers of smaller birds such as parakeets; only when they are initiated into adulthood may they wear the elaborate headdresses of blue macaw feathers. Researched by Rylee Williams

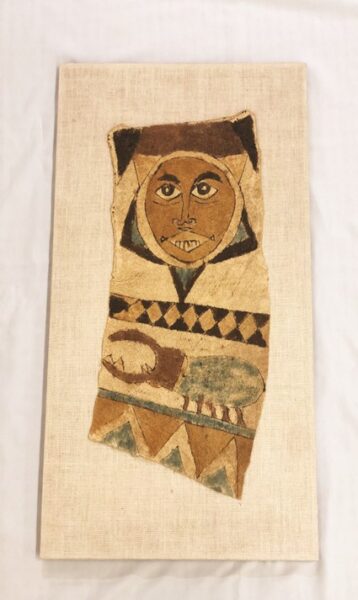

Tukuna culture

20th century

Bark cloth and pigments, L. 22 cm x W. .3 cm x H. 46 cm

BFPC collection #2017.5

Bark cloth hood masks are worn during the culmination of a Tukuna girl’s coming-of-age ritual, which is known as a Pelazón ceremony. In this ritual, the Tukuna girl spends a year in near-total isolation after her first menstruation; the only person with whom she may have contact is her grandmother, who teaches her important skills such as weaving. At the end of the year, the girl is welcomed back into the community as a woman during the Pelazón ceremony.

The symbolism of a sun-like face and a stag beetle on this bark cloth hood likely derives from a myth of the neighboring Yuparí culture, which features a heroic solar character as well as forest demons who create insects and reptiles. During the Pelazón ceremony, the members of the community dress up as these demonic figures, carrying musical instruments and phallic objects to represent temptations that will be presented to the girl throughout her life. Researched by Rylee Williams

Navajo/Dine culture

20th century

Wood, feathers, cloth, and pigments, L. 9 cm x W. 9 cm x H. 18 cm

BFPC collection #2012.44

This is a Navajo/Dine culture kachina dancer figure that wears a Kokopelli helmet mask.

The Navajo/Dine peoples adopted some of the Pueblo religious practices after they moved into the American Southwest, but they adopted the making of kachina figures primarily to create art objects for sale in the tourist trade. This figure accurately reproduces the Kokopelli helmet mask that is worn by kachina dancers during Pueblo kachina season rituals.

While the Kokopelli character is depicted in petroglyphs and pictographs as a flute player with a hunched back, Kokopelli dance masks are identifiable by their phallic cornhusk snout. Both the flute and the cornhusk snout suggest the lascivious nature of this character, who is associated with male seduction and fertility. Researched by Rylee Williams

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu