Archive for August, 2018

Hope in the fight against HIV

In the 1980s and 1990s, an HIV diagnosis was a death sentence.

With the development of a cocktail of prescriptions, survival rates skyrocketed.

Still, about 50,000 people in the United States are infected with the virus each year. And one out of every eight people who is HIV positive doesn’t know it.

Dr. Amy Hulme, assistant professor of biomedical sciences, studies the inner workings of the virus and how it replicates. She hopes her work will lead to the development of a vaccine or better drugs to prevent transmission.

In the last 10 years, she published 11 articles on this research in publications like the Journal of Virology. She also served as a peer reviewer for this journal.

Hulme is fascinated by HIV because it does a few things that really should not work. It is unique among viruses because it mutates, making it difficult to predict the usefulness of medication.

It is also unique because it is one of only two human viruses classified as a retrovirus. HIV gained this classification based on how it copies itself inside a cell. First it transfers the RNA genetic material of the virus into DNA – a process called reverse transcription. That DNA then gets inserted into the cellular DNA.

Reverse transcription, explains Hulme, hardwires the virus into the cell. But in order for the reverse transcription to occur, the coating of the virus has to be shed.

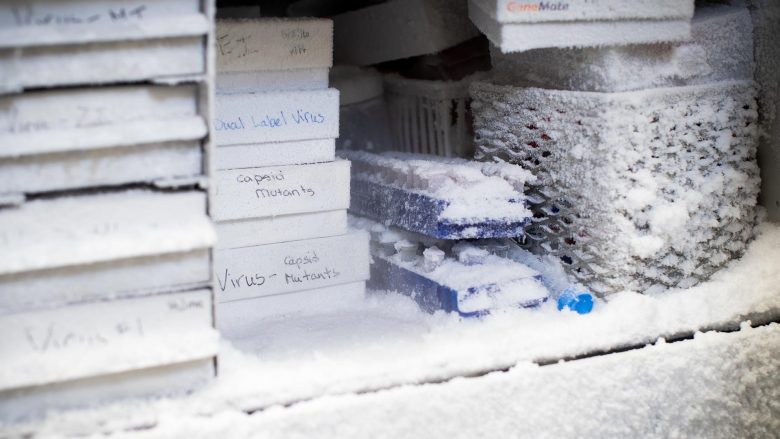

In Dr. Amy Hulme’s lab, she studies how HIV replicates itself in cells. Specifically, she looks at the how and when the capsid (or coating) comes off. Photo by Kevin White

Shift in thinking

Or at least that’s what the scientific community originally thought – that it was a linear progression from the uncoating to reverse transcription. No one truly knew how and when this uncoating occurred – or the significance.

Her post-doc adviser, Dr. Thomas Hope from Northwestern University, believed that the virus entered a cell and the coating fell off immediately. Many others in the field thought uncoating happened before reverse transcription.

During her post-doc work, Hulme discovered something different. She observed the virus copying DNA in cells while it was still coated.

“It was my ‘a ha’ moment,” Hulme said. “It made me think, ‘maybe the steps kind of happen at the same time.’”

If the coating stayed on, would the DNA ever become one with the host cell? Hulme knew that the biological community would benefit greatly from further studies on this step. After all, blocking the uncoating step might mean a medicine or vaccine could be developed to prevent HIV.

Hulme established an experimental technique using an instrument called a flow cytometry. This device analyzes particles in a fluid as they pass through a laser. Since she developed this new technique, it has been included in numerous studies – by her and others in the field – to dissect the how and when of the uncoating process.

Dr. Amy Hulme created two experimental techniques to help study HIV. Photo by Kevin White

Medical mysteries

Owl monkeys have a protein that blocks HIV replication, so they have been key to this research.

Hulme delivered a drug to cultured owl monkey kidney cells, which affected how that immunity protein stuck to the coating. Then she removed the drug at different intervals and used a flow cytometry to determine how much of the virus was coated and uncoated at each stage.

If the virus was uncoated, she noted, it could no longer be protected by this restriction protein.

The other method Hulme’s lab uses for HIV research incorporates fluorescent microscopy.

In this method, she and her students label the virus with fluorescent proteins. Then, the proteins will glow under the microscope and can be monitored to detect the coating at different times.

“If you get the same answer with both techniques,” she said, “you can be much more confident that result is a real result, and not due to some weird experimental artifact.”

Uncoating seems to impact a lot of other steps that happen kind of at the same time, and immediately after it. It’s an important step to understand, it’s just very difficult to study. — Dr. Amy Hulme

Her studies determined that the majority of uncoating happened within the first hour.

“When we delay reverse transcription using a drug, we also delay the process of uncoating,” said Hulme, which leads her to the conclusion that there is some interplay between the steps. “It’s becoming very clear that it is a very central step that affects a lot of different steps in HIV replication.”

Hope is proud of the impact Hulme has had on the field.

“She had great success tackling a major research mystery in the HIV life cycle,” said Hope. “Because her approach was unique, it was controversial in the field at first. But ultimately, she was correct.”

Now that there is more understanding on the process, Hulme is beginning to look at how untreated AIDS makes its way to the brain and causes neuro-cognitive disorders.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Past, present and power

Dr. Billie Follensbee, an art historian and archaeologist who specializes in ancient Mesoamerica, has spent years illuminating a fundamental aspect of humanity in artifacts from the Olmec civilization, which once thrived along the Gulf Coast of present-day Mexico.

Olmec civilization is famous for dramatic, blocky sculptures that often appear androgynous.

Follensbee says, “The faces are often very naturalistic, but the bodies tend to be very stylized. Because of that, it’s difficult to tell whether a figure is male or female.”

She set out to catalog Olmec sculptures by sex and gender, but she struggled to find consistent guideposts in the existing scholarship.

“The only pattern was that if it was large and important-looking, it had been classified as male. And if it was small and unimportant-looking, it was assumed to be female. Basically, indications of power were automatically considered male.”

Dr. Billie Follensbee studies and teaches about art and artifacts from non-Western cultures including Africa, Oceania and the Americas. These African masks are from the Mace collections donation to Missouri State. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Patterns

This paradigm, Follensbee believes, reveals more about those who first chronicled the Olmec than about the Olmec themselves.

“There was a great deal of gender fluidity in Native American cultures, which was originally left out of history books because the people who recorded it were from Western cultures, where gender roles are traditionally rigid,” she says. “They were uncomfortable with this fluidity, or they just didn’t understand it.”

To avoid making similar assumptions, Follensbee needed a Rosetta stone, a way of decoding the sculptures that wouldn’t perpetuate biases of pre-existing research.

She turned to Olmec ceramic figurines, which she says, “are much more clearly sexed than the sculptures.” By carefully cataloging body forms, jewelry and clothing associations, she created a lexicon of male and female characteristics. Since these associations remained roughly consistent over several centuries, they could reasonably be assumed to appear in Olmec sculptures, too.

And, Follensbee found, they did. Many were subtle, but straightforward. For example, identifiers included: pinched waists and wide hips for women; straight-sided waists for men; high-waisted, wide belts and skirts for males; low-slung skirts and thin, beaded hip-hugger belts for females.

Follensbee’s lexicon provides a clear methodology for identifying gender in Olmec sculptures, one that isn’t influenced by an artifact’s size or apparent importance. She published these findings in a series of articles, the latest as a chapter in the volume “Dressing the Part: Power, Dress, Gender, and Representation in the Pre-Columbian Americas,” which she co-edited with Dr. Sarahh E. M. Scher.

Of course, it sometimes gets complicated. A figure with anatomically female features might wear clothing associated with males, or a figure might have male features and female paraphernalia.

“The conclusion I came to,” she says, “was that they were appropriating the power of the other gender. A man might be appropriating the idea of motherhood, or a woman might be assuming hereditary power from her father. Or she could be fulfilling a role that may have traditionally been male — such as a ruler — but was in this instance taken on by a woman.”

And sometimes gendered characteristics were intended to convey a completely different meaning. “For example,” she says, “one male figure wore a weaving tool that is typically associated with females. But this was a man outside of the Olmec area, and he was likely adopting this to show that he was associating himself with the Olmec, rather than as a feminine symbol.”

Altogether, it points to a complex understanding of men and women within Olmec society, one that resonates today.

Dr. Billie Follensbee’s latest research explores art and artifacts from ancient Native North American cultures. Follensbee and her two student grant assistants, Sarah Teel and Leslie Dunaway, created these birdstone reproductions. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Perspective

Follensbee’s research provokes discussion in the archaeological community.

She says, “Some people become upset because they say that this is ‘revisionist history.’ But it’s just correcting misrepresented history. In the past, if a scholar found the grave of a man wearing a gold headdress and expensive garments, the tendency has been to say, ‘This must be a king.’ But for the grave of a woman who had the same precious ornaments, the conclusion was, ‘In this culture, it must have been prestigious to decorate the grave of your wife.’”

These assumptions have had the effect of obscuring women within the historical record. Follensbee says, “If a figure wasn’t absolutely, obviously female, it was assumed to be male.”

And, she contends, determining the true gender of an important sculpture is far more than an academic puzzle. It has real implications for how we think about our world now.

“People sometimes characterize the concept of women in leadership as a new idea — as if women have never held positions of power before. When we look at the archaeological record from all over the world, however, we find powerful women throughout history,” she says.

“This research not only tells us about these objects. It tells us about ourselves.”

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Main photo by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams