Psychology study takes unique look at visual learning

You don’t have to pay conscious attention for minutes to identify each and every vehicle. This is because of past experiences: With repetition of events, such as observing types of automobiles you see frequently, there is an increase in familiarity. As a result, there is a decrease in neural activity regarding these automobiles and your conscious attention is directed elsewhere.

But wait — a DeLoreanwith a flux capacitor has moved next to you. It catches your attention … and in all likelihood, you take longer looks at the DeLorean and your heart rate decreases.

To psychologists, these looks and this change in heart rate are physiological signs that you are having a “response to novelty” and are actively encoding new information. If you saw the DeLorean regularly, it would be what they call a “habitual experience.” Your visual attention to the car would decrease, and changes in your heart rate would not occur.

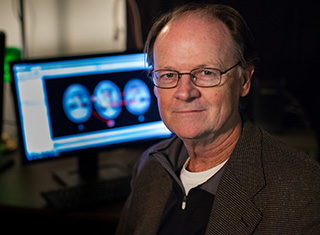

Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State, is in the first phases of a three-year study to examine visual scanning patterns, and associated heart-rate changes, in both infants and adults.

Psychology professor starting a study on visual scanning, changes in heart rate

How quickly a person habituates to experiences is tied to physical and mental development.

Babies who are 2 to 3 months old may look at a new object for as long as eight minutes, learning its visual characteristics. In just a few more months, if they develop normally, they scan the object more exhaustively and quickly.

As an infant pays visual attention to a new object, his or her heart rate tends to decrease. How much it decreases, it is argued, reflects how much information is learned about the new object.

At-risk populations — for example, individuals with mental retardation, attention deficit disorder or schizophrenia, and infants with developmental delays — tend to visually scan new objects differently than normal individuals. The at-risk individuals may continue to take longer looks and may never fully habituate to some experiences. Autistic children, for example, do not look at faces the way others do — they tend to avoid looking at emotion centers such as eyes, noses and mouths, which are the areas of the face most individuals scan first.

Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State, is in the first phases of a three-year study to examine visual scanning patterns, and associated heart-rate changes, in both infants and adults.

He hopes the research leads to new ways to detect developmental problems in infancy or early childhood, then to the creation of new intervention methods to improve visual learning. Hopefully, the findings will prevent developmental delays in at-risk infants and young children.

Eye-tracking technology leads to exceptional amounts of data

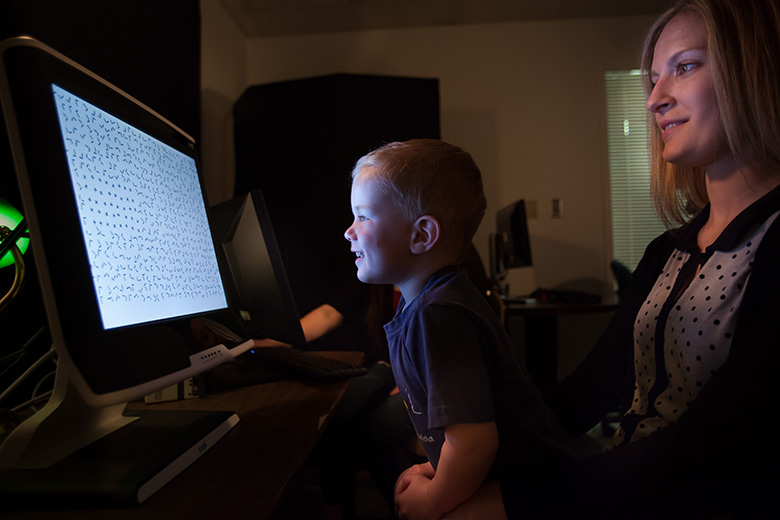

Mitchell and his students place research participants in front of an apparatus called a Tobii eye tracker. Tobii looks like a regular computer monitor, but it’s really collecting a gold mine of visual data. The participant is also attached to electrodes via a separate computer and laboratory system. These record and monitor heart rate.

Next, the participant is shown a series of black-and-white images on the Tobii screen.

“We try to develop stimuli that are something you’ve never seen before,” Mitchell said. He and his students design abstract shapes, make line drawings of animals and modify photos of faces.

“The more we can understand developmental and individual differences in visual learning and scanning, the better we can develop appropriate interventions to help those infants and young children with learning deficits.” — Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell

Tobii’s software compiles information about where the participant has looked, how many times they looked there, how long they looked and how rapidly they responded to different areas of the image. Researchers can then compare visual patterns created by those with and without developmental delays or disabilities.

“This gives us more data than we could even hope to get elsewhere,” said Bret Eschman, an experimental psychology graduate student. “It gathers so much information so quickly.”

This data is unique to Missouri State: Although the Tobii is increasing in popularity among researchers, it appears few are using it to study early visual development. Mitchell said he doesn’t know of any other infant researchers who are investigating both visual scanning and changes in heart-rate data at the same time.

Mitchell’s study started in January. He hopes to test at least 200 to 300 participants, ranging from ages 4 months to adult.

“The more we can understand developmental and individual differences in visual learning and scanning,” he said, “the better we can develop appropriate interventions to help those infants and young children with learning deficits.”

It’s fascinating to me that we’ve had the technology for tracking eye movements for decades but it hasn’t been adequately applied to research! How does one become a research participant, I’m also a student at MSU and am greatly interested in participating and possibly volunteering in order to learn more about how research studies are designed, proposed, and implemented.