Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ category

Selected works by Sarah Perkins

Walstrand Walls

This is from a series that I was doing with Gwen Walstrand, based on what we’ve seen in Cairo, Illinois. She takes pictures, and I respond to the photographs that she takes. I really like the idea of it sort of getting double translated, her interpretation of it and then my interpretation of her interpretation. I like that idea of people influencing each other. Sarah Perkins

Building photos by Gwen Walstrand • Bowl photos by Tom Davis

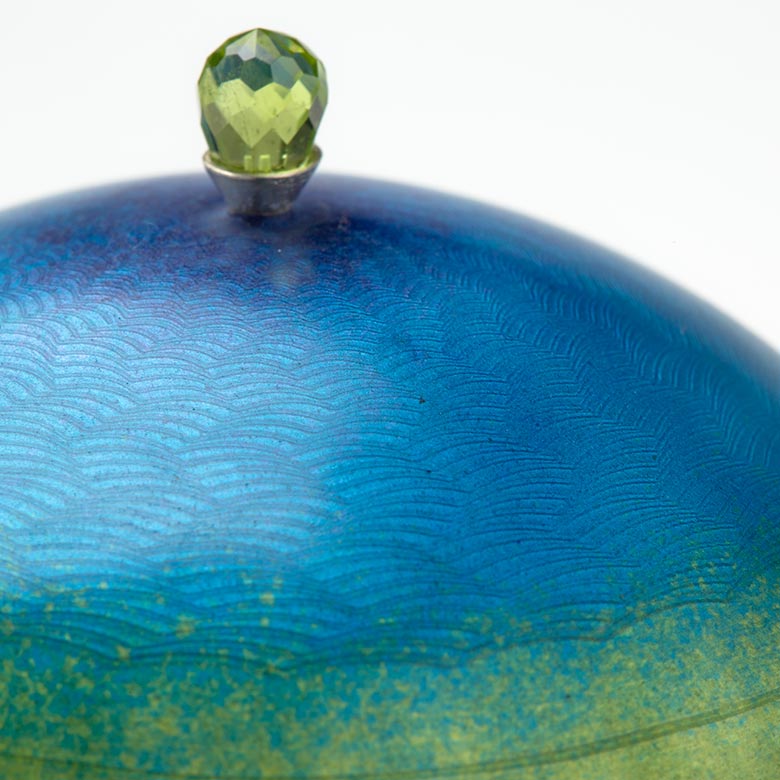

Perkins loves to play with texture and draws inspiration from a variety of sources. She says that for this vessel, called Gourd, she made the surface “smooth and satin like the skin of a vegetable so you’d want to touch it.”

Cactus required Perkins to hand-drill 300 holes in the body of the vessel. She then inserted wires at precise angles so they would stick out in proper proportions. She finished the piece by soldering the wires to the vessel and melting their ends.

Perkins says, “My work is changing right now, and I’m getting a much brighter color palette than I have before. I think having gone to India had a lot to do with it.”

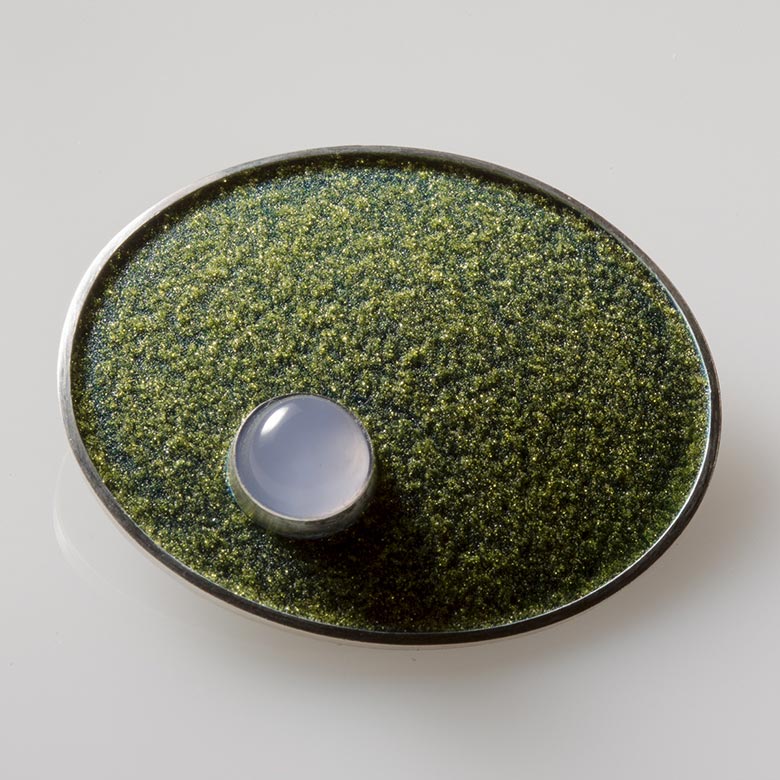

In Roe, Perkins employed an ancient technique called ‘granulation,’ which uses chemistry, evaporation and extremely high temperatures to fuse tiny balls of metal onto a larger piece without any solder. It took her days just to place the metal balls.

“I’m interested in getting down to the formal fundamentals,” Perkins says. “Shape, texture, color and nothing else.”

Perkins looks to the natural world for textural references and combinations. About this piece, Lichen, she says, “I like for the inside and outside to be different. So the inside may be smooth and shiny, but the outside is rough and tactile.”

Perkins’ jewelry often plays with graphic, minimalist combinations. Of this piece, she says, “I like the texture of the druzy stone, which I bought as a piece, next to the texture of the enamel.”

Historical art and fashion inspire some of Perkins’ pieces — like this one, which was crafted to look like the gores of a ball gown. “I thought it looked like Cinderella’s dress,” she says.

Perkins mixed red glass seed beads in with a range of red enamels. “The beads’ melting temperature is a little higher than enamel,” she says, “so it’s got that mottled quality like moss.”

Perkins says this group of jewelry is largely “about what’s perfect placement at the moment. Maybe an hour later, I would’ve put that stone in a different place. But right then, it was very deliberately exactly there.”

Photos by Tom Davis

Answering big questions through statistics

Resiliency testing is just one example of many research projects Dr. Erin Buchanan, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State University, has published in recent years. She collaborates with undergraduate and graduate students in her statistics lab as well as with a clinical psychologist at University of Mississippi, Dr. Stefan Schulenberg, on many projects regarding the meaning in life.

“How does meaning in life affect negative life outcomes? That’s the big, broad question. Then we narrow it down to, how does a scale work in predicting negative life outcomes? Does it work the same way for everyone?” said Buchanan. “By negative life outcomes, we mean depression, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, drinking – those sorts of things.”

Clinical people say this a lot, “The right therapy for the right patient at the right time,” or something to that effect. Computer-adaptive testing is built on that. “The right question for the right person at the right time.”

Adding technology to the equation

Buchanan’s role in research projects is to develop scales, test the scales to see if they measure what was intended, and to analyze the variance across demographics. Currently, she and her students are in the midst of testing 47 unique scales with students in introduction to psychology classes. She also collects results through MTURK, Amazon’s answer to incentivized testing.

As a daughter of two computer programmers, she said she felt like the black sheep entering the field of psychology, until she realized that as an experimental psychologist focusing on quantitative analysis, she spent much of her time programming, too – in approximately 12 different languages.

“I’ve always been good at math. I knew I never wanted to work directly in a helping profession. That was never my goal,” she said with a laugh.

Just the way you phrase things can change whether a respondent will say yes or no. Just because it’s culturally relevant.

One of the most prominent projects for Buchanan is to develop a computer-adaptive test. This test starts with an average score, but depending on how a respondent answers, the following questions may be more positive or negative, or might increase or decrease in difficulty.

“Social desirability can come into play, where people will go, ‘Oh, you want me to say positive things,’ or you end up with all happy or all negative answers, and you don’t get anything in the middle,” she explained. “We’re trying to statistically stretch the scale out so we might be able to better predict the negative-life outcomes that come with that.”

Answers divided by race

In the early 2000s, the south suffered two major disasters. After Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill, Schulenberg, director of the Clinical-Disaster Research Center at Ole Miss, contracted with Buchanan to test the resiliency of the people of the area.

“I hear this a lot from clinical students, ‘Why do I need statistics? I just want to help people.’ My answer is, ‘Because you have to be able to read these articles and understand the implications the variations in responses people make.'”

“We have a primary focus in disaster mental health and a secondary focus in positive psychology,” said Schulenberg. “Dr. Buchanan has been a tremendous asset to our team for a number of years incorporating sophisticated statistical analyses.”

The resiliency scales were found to be valid and effective, but analysis showed differences between white and black respondents.

“While we end up with the same overall score, white participants were much more likely to have a real short spread of scores. They would only pick the middle, while the black participants would pick the entire range,” she said. “If you’re black in Mississippi you’re much more likely to be one or two steps below socioeconomically. Obviously that’s going to matter for resiliency, right? We were trying to argue that the effects weren’t due to innate resiliency of people, but more due to circumstance.”

Previous research had shown that culture-fairness plays a part in standard and computer-adaptive testing, sometimes resulting in artificial differences because respondents inferred something into the question that might not have been intended. Similarly, Buchanan noted that black people from an early age learn a different dynamic of power and authority, causing differences in way they may perform on tests. So, word selection is key – whether it’s a test about your resiliency or a statewide mandated comprehension test, the testing agent desires representative results.

An everyday life of Biblical proportions

“The house I grew up in and every school I went to was destroyed,” said Matthews. “Much of me went away in the sky, and yet I was able to go back down there and identify what was remaining of the structure that was my childhood home.”

Matthews took a picture of the ruins and uses it in class as a way of talking about how space is still present in our memories. This speaks to his area of expertise: the history and culture of the Biblical era. Though physical remains may be few, the everyday lives of the people from this time can be better understood by studying the stories and artifacts that they left behind.

‘What the devil are they doing?’

How do we learn more about the ancient world? This is one of Matthews’ research questions. He says it’s important to understand that we tend to filter everything through our modern scope.

“We are trying to find out what the devil they were doing. Unfortunately, this often means applying our modern viewpoint and totally skewing the whole thing.”

Biblical narratives, like most stories, assume that the audience shares a defined set of social understandings or customs. When we don’t know what these customs are, we must use several different methods to try to discover them.

“I have made good use of modern research and analytical methods in the social sciences —sociology, anthropology, psychology, communications — to evaluate the ‘human moments’ in the narratives,” said Matthews. “For example, when I examined the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38, I looked for the social cues in the story: clothing, marriage status, power relationships, gender, speech patterns and the physical placement of the characters.”

Matthews applied these methods when writing and researching his most recent publication, the fourth edition of “The Cultural World of the Bible: An Illustrated Guide to Manners and Customs.” It is one of 17 books he has authored, and he has published numerous articles on the subject as well.

Putting together a large puzzle

“When we say cultural world, what it basically says to people is that we’re going to talk about everyday life. What did they eat? What did they wear? How did they celebrate? What were their burial practices? What kind of weapons did they use?” he said. “All kinds of topics like that.”

There are several ways we can learn the answers to questions like these: written records, including the Biblical text and extrabiblical documents; physical remains such as tomb paintings and grave goods, garbage heaps, and the ruins of buildings, which are studied by archaeologists; and the study of both modern and ancient cultures via analogy.

“Reconstruction of the world of ancient Israel is like putting together a large puzzle,” said Matthews. “Some of what I included in the book came from my own travels in the Middle East, some from basic research and discussion with colleagues, and some from studying how other authors shaped their treatment of the subject.”

Talking about talking: analyzing conversations

Matthews, who has been a Biblical scholar for more than 30 years, has also recently focused on the conversations that occur in these Biblical narratives and what they can tell us about the characters and their daily lives.

“There is a lot of conversational analysis in communications, sociology, anthropology and psychology,” said Matthews. “I got interested in seeing how the different disciplines analyzed conversation, but, of course, what I’m working with is text. I have narratives with embedded dialogue.”

“It allowed me to develop a richer understanding about the setting of the story, the human drama associated with a childless widow, the importance of clothing as a social marker and the role that place—physical location—holds in determining how humans interact.” (Matthews on studying the human moments in narratives.)

Matthews studied the way these disciplines researched conversations, which mostly consisted of analyzing live conversations. He applied many of the techniques and concepts they used to the narratives he was studying and was able to discover previously unknown contexts. His book, “More Than Meets the Ear: Discovering the Hidden Contexts of Old Testament Conversations,” was published in 2008 and led to a journal article in 2014, “Choreographing Embedded Dialogue in Biblical Narratives.”

Matthews graduated from Missouri State in 1972 with a bachelor of arts degree in history, and received his masters and doctorate in Near Eastern and Judaic studies from Brandeis University in 1973 and 1977 respectively. He has spent most of his career focused on the historical aspects of religious studies, and looks forward to continuing his studies on ancient Biblical culture and writing about what daily life was like thousands of years ago.

Further reading

Small particles, big impact? Exploring how nanomaterials decompose

Silver, known for antibacterial and anti-odor properties, may be in everything from athletic wear to cutting boards. Zinc oxide, which prevents sun damage, has been used in sunscreen and woven into fabric for clothing. Carpet may be treated with nanoscale materials that prevents it from absorbing spills. Carbon-based nanomaterials are found in cell phones and televisions.

One thing is sure: The trend of nanotechnology means we are all more likely to buy goods with these tiny particles, and, later, dispose of these products.

What’s less certain is the affect of these nanomaterials on the environment as these goods decompose in landfills.

“I wanted to do research with undergraduate students, not just students studying for a PhD. Here are Missouri State, some of my best research has been done by undergraduates.” — Dr. Adam Wanekaya

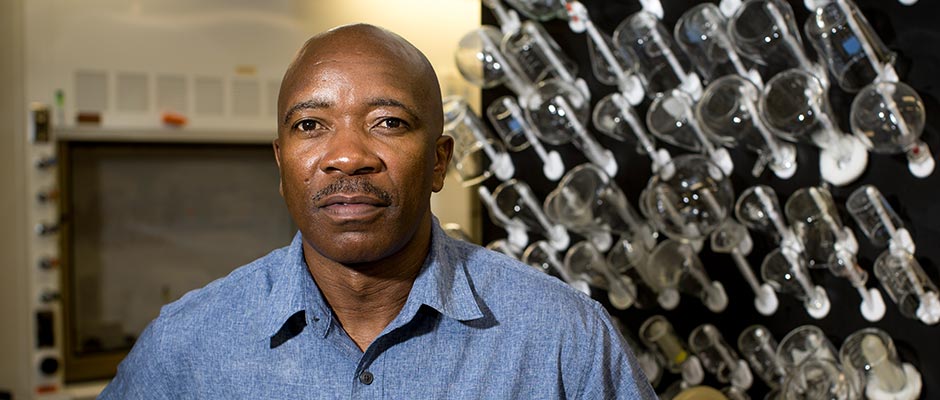

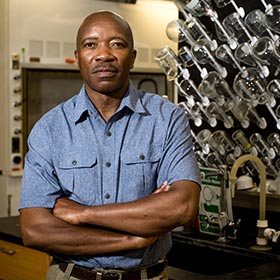

Dr. Adam Wanekaya, associate professor of chemistry, has researched nanomaterials since his days as a doctoral student in the early 2000s.

For the last three years, he has been leading a project with undergraduate and graduate students at Missouri State who are studying how nanomaterials age in an accelerated weathering chamber. The research shows how these particles will react in conditions similar to those they would experience outdoors.

“What is the fate of those particles after three, 10, 20 years? We want to make sure they don’t contribute to diseases such as leukemia, or cause harm to plants, animals or the environment,” Wanekaya said. “Some of us recall how asbestos was previously thought to be a wonder material, only to later realize it was the cause of many deadly diseases.”

African collaborations

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is originally from Kenya, and came to the U.S. for doctoral studies. He started working at Missouri State in 2006. He is currently part of the Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program, which encourages collaboration between scholars from Africa who now live in Canada or the U.S. and scholars who currently live in Africa.

Wanekaya traveled to a university in Nigeria for six weeks in 2015. One scientist he met there, who works with solar cells, came to Missouri State in January 2016 and planned to stay for six months to engage in research on campus.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Creating conditions that mimic the outdoors

At least once a week, senior Molly Duszynski heads into a chemistry lab at Temple Hall.

First, she attaches carbon nanotubes to glass slides.

Next, she takes the slides to an accelerated weathering tester, where they fit into holders designed for them.

“It has been really awesome to learn about carbon nanotubes and the overall process of real research.” — Molly Duszynski, biochemistry/microbiology double major

Now, the chamber is closed. It’s time for Duszynski to make decisions about what kind of conditions the slides will face. The chamber has UVA-340 bulbs, which provide the best possible simulation of sunlight. It is also attached to a tank that holds water free of minerals or impurities. She, Wanekaya or others on the project may adjust lighting, humidity, temperature and more to simulate sunlight, rain and dew. The chamber can create conditions for night, evening, afternoon or morning, or cycle through those.

In a few days or weeks, the machine can reproduce the decomposition that would occur in months or years outdoors.

Wanekaya’s team has chosen to mostly focus on conditions that are slightly hotter than normal, in order to see what the carbon nanotubes would do if they were in a landfill in a part of the country with high-intensity sunlight.

They chose carbon to study first.

“This is a good basic material because we can predict a bit about carbon’s behavior,” Wanekaya said. “We are starting with something more simple before we move on to something a bit more complex.”

Approximate conversion chart

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula for how many hours in a weathering chamber equals a time period in the outdoors, according to Q-Lab (the company that makes the QUV Weathering Tester used in MSU’s chemistry lab). That’s because the relationship between tester exposure and outdoor exposure has so many variables, such as geographic latitude of the exposure site, altitude, random variations in weather from year to year, etc. One recent graduate student in Wanekaya’s project, however, was using this approximate ratio: 2,100 hours of weathering tester exposure = About one year in the Florida sun

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Preliminary results, collaborative papers

Wanekaya says the research is yielding some preliminary results.

The team can see that the shapes of the carbon nanotubes change after treatment in the chamber. Before treatment, the nanotubes are more or less linear. After, they are coiled. Using various technologies, the team has shown there are other substantial differences between groups of control nanotubes, which are not subjected to tests, and nanotubes that have been aged.

“Now, we need to find out whether those changes are good, bad or neutral. That’s our next step,” Wanekaya said.

The team shared a tested group and a control group with colleagues in the Missouri State biology department. Those researchers exposed yeast, bacteria and other cells to both the control group and the aged group of nanotubes. They wanted to see if either group of nanotubes was potentially toxic to those materials.

One team found that treating yeast with either aged or control carbon nanotubes was significantly toxic to the yeast cells. Results of that study have been submitted for publication to the Journal of Nanoscience and Technology.

No significant differences were observed in bacteria and plants exposed to both the aged and control carbon nanotubes.

Wanekaya plans to keep working with these tiny particles.

“Nanomaterials are very exciting. They have novel properties that can be used for so many things.”

How small is nano?

In the International System of Units, the prefix “nano” means one-billionth. Therefore, one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. It’s difficult to imagine just how small that is, so here are some examples:

- A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick

- There are 25,400,000 nanometers in one inch

- A human hair is approximately 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide

- One nanometer is about as long as your fingernail grows in one second

Source: United States National Nanotechnology Initiative

Wanekaya’s other research interests

Dr. Adam Wanekaya is seeking many ways to use nanotechnology to benefit humans and the environment. He is involved in research regarding:

- Cancer treatment (part of a team that received a grant from the National Institutes of Health)

- Cancer detection

- Detecting and removing toxins from the environment

For more about his work regarding cancer, see a past Mind’s Eye story about one of Wanekaya’s collaborators.

Further reading

A working writer

The pitch was going well; the executive was laughing and taking notes. But then she asked an unexpected question. Could he change the gender of one of the lead characters? A female lead would be more inclusive of the network’s demographics and provide a vehicle for one of its rising stars.

Amberg remembers that it wasn’t as simple as saying ‘yes.’ He had to quickly run through the plot, scanning for the “ripples that come from tossing that rock in that pond. I knew the story so well that I was able to do that in the moment. The fact that I was able to answer authoritatively about the specifics of how I’d adjust the story gave her the confidence to buy the project in the room.”

With that sale, Amberg earned membership in the Writers Guild of America, a life-changing milestone that resulted in larger contracts and meaningful benefits. The experience also affirmed an essential principle: that flexibility is the foundation of life as a working screenwriter.

Now, as the coordinator of Missouri State’s screenwriting programs in the department of media, journalism and film, Amberg helps emerging writers develop their skills and learn to navigate the industry.

Amberg’s creative activities keep his knowledge sharp. Since joining Missouri State in 2013, he has completed contracts with Disney Channel and Cartoon Network. He makes regular trips to Los Angeles, where he meets with contacts at film, TV and Web entertainment companies, including Nickelodeon, Amazon and Awesomeness TV. His work has been recognized with a number of awards, including Best of Competition in Faculty Scriptwriting at the Broadcast Education Association Festival of Media Arts.

Lessons from the industry

Amberg is straightforward with students about the industry’s unpredictability. Companies’ mandates shift; executives get reshuffled; different personalities respond to different types of material. And these all affect whether a writer’s work gets produced.

But Amberg also focuses on the constants, like the importance of developing a strong work ethic, mastering the fundamentals of story and – most importantly – understanding the writing process.

“I don’t want anyone to be in a situation where they find themselves staring at a blank screen,” he says. “I want them to know how to tell a character-based story that is held together by the tools of writing, not dependent on one idea. And if they get some great, awesome idea, they will be able to execute it. And if they get hired onto a project, they’ll know how to deliver the best version of someone else’s idea.”

Amberg also encourages humility and perspective. “Everyone in this business is working hard, and no one came to Los Angeles with the goal of making someone else’s dream come true. It’s important to be kind to other people and assume that everyone’s doing their best. And when the planets align and a project works, it’s great.”

Amberg often shares with students that when he first started out, he believed compliments indicated a meeting was going well. As he gained experience, he learned that questions, not compliments, are the true sign of a project that’s resonating. “When people are really interested in something, they want you to make changes,” he says.

This dynamic can feel bruising to creatives, who are sometimes considered overly protective of their work, and Amberg empathizes. “Screenwriting is unlike many other kinds of writing, where the writer is king,” he says. “But it’s important to remember that the executives you work with are smart, creative people, too. They’re tasked with thinking strategically about multi-million dollar projects. And their changes aren’t arbitrary; they just have more information about what they need.”

According to Amberg, the ability to collaborate and create a production-ready script is essential, not only for career success but for the strength of the story.

“You love your script,” he explains. “So you change it and adapt it to survive in the market – the same way you’d raise a child to survive in the world.”

Fighting the past for a more active future

To Perkins, this wasn’t a surprise. She has spent much of her career analyzing underrepresented populations, such as African Americans and the elderly, in the areas of exercise and sports psychology.

“African American women are one of the least active segments of the population,” Perkins said. “In Springfield and on campus, we have a small African American population, so I want to know if they exercise, if they use the recreational facilities on campus and their perceptions about exercise and campus climate.”

Her experience at the Rec Center inspired her to begin researching exercise trends among female African American students at Missouri State with the ultimate goal of developing a new physical activity program designed to revolutionize exercise trends at Missouri State.

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Researching the underrepresented

Perkins’ research into minority groups indicates that a population’s overall trend of activity exists due to a complex variety of external factors – such as community, education and environment – as well as internal factors. Her research into these factors helps her to understand the best methods for improving exercise trends for different groups of people.

“In kinesiology, we prescribe exercise just like a doctor proscribes medicine.”

“In kinesiology, we prescribe exercise just like a doctor proscribes medicine. Not everyone should be doing the exact same workout. The same strategies don’t work for everyone,” she said.

In the past, Perkins has investigated several possibilities that may explain why African American women are less active.

For instance, her research has shown that African Americans in general may have less opportunity for participating in sports and other physical activities that are primarily offered in white communities. This lack of opportunity for activity early on in life can lead to lifelong habits that require extra help and effort to change.

“Everyone deserves help,” Perkins said. “Groups of people that are not represented in research are unlikely to be getting that help.”

Photo by Jesse Scheve

Encouraging exercise to prevent disease

As a researcher, Perkins’ goal is to understand these psychological and social factors about physical activity, but she doesn’t stop there – her goal is also to change the statistics by breaking through the barriers with targeted interventions to help these women get out and get active.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2011, African American women were 80% more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic white women.

According to Perkins, the importance of exercise can’t be overstated. She said a lack of physical activity can negatively affect a person’s health and lifespan in many ways, and it is troubling that an entire demographic group is at risk for insufficient physical activity.

“Exercise can prevent chronic disease, which is a fact a lot of people just aren’t aware of,” Perkins said. “I want to figure out what psychological factors influence sedentary behavior and what social or cultural factors lead to African Americans being less physically active and having a higher incidence of obesity and chronic diseases.”

Empowering a diverse campus to meet the needs of every individual

After collecting preliminary data about physical activities among female African American students, Perkins received a small cultural diversity grant from the Association of Applied Sport Psychology to further develop the study. She conducted focus groups to learn more about the perceived barriers to a workout regime, and most prominently she heard “lack of time” and “lack of motivation.” In her initial analysis of the responses, though, she also uncovered some findings more unique to the demographic, like difficulties with dealing with hair post workout and feeling socially isolated.

She hopes that by providing opportunities for some of the students most likely to have experienced obstacles to physical activity, she can contribute to a campus environment that is not just healthier, but also more inclusive of its diverse population so every individual can be empowered to meet his or her needs.

“I ask them: In a perfect world, what would an exercise program look like for you? Ultimately my goal is to help get students moving. I want to get them now in college so they’ll continue to be active as adults after they graduate,” she said. “If I can figure out what barriers prevent them from exercise, I can help them find a program they can stick with so that they can live healthier lives. It’s about finding what best fits the needs of the people you work with.”

Rethinking education: How to engage students who have special needs

“Research shows that 20 percent of students have these disorders throughout their childhood. A lot of those things that go untreated and unhelped get worse as students get older,” said Adamson, an assistant professor of counseling, leadership and special education at Missouri State University. “It tends to be a high need.”

So she wondered about the possibilities. What if teachers knew how to better identify and help such students? What if those students knew how to seek help for themselves? And how might that bring about a better future for tomorrow’s leaders?

Identifying the problem

Adamson is working with local public schools to help a small section of students who struggle with following through on classroom engagement and aren’t learning at the same rate as their peers. Specifically, she wants to know what systems, supports, and interventions can be placed in schools to support teacher training and student outcomes.

Such students may have educational behavioral disorders, which differs from medical behavioral disorders. The question is whether the disorder affects performance in the classroom.

“It isn’t because they aren’t capable,” Adamson said. “It’s because they aren’t able to sit in class and sustain until the class ends.”

What happens then, Adamson explained, is a cyclical issue in which entire classes fall behind as teachers reteach the same content to try to catch those students up.

Using a single case design, her research focuses on like groups of students to find direct relationships between interventions and how teachers’ and students’ behaviors change on days when data are collected.

Getting teachers to think like movie stars

However, the answer doesn’t lie in addressing behavioral concerns with the students alone, Adamson noted. Focus on adjusting the behavior of the teachers from an entertainment angle, and better engagement will follow.

“We know the key to students being successful is having dynamic teachers,” she said. “The biggest impact on students staying in school and having good outcomes is school engagement, which comes from making a connection with the school.

“As teachers, we’d better be the best actors there are. Every day that we’re teaching a class, we’re putting on a performance. We’re trying to draw students in as the crowd so they walk away, remember the lesson, and want to tell everybody about it.”

Behavior management is also the top reason teachers leave the profession, Adamson said, noting that training the teachers and getting students to become engaged could change a child’s trajectory.

“Kids who have emotional and behavioral disorders have worse post-secondary outcomes such as not going to college, not getting jobs and going to prison,” she said. “They’re starting out on this horrible track. It’s our job to find out what we can do to help improve this process for them.”

“I think as a nation, we need to support students who have mental illnesses and people who have mental health issues in general. Those kids who have behavioral disorders really struggle understanding the context of school because it’s so different from their lives and environments they’ve been in.” — Reesha Adamson

The long-term benefits

Starting students on a better track also includes helping them manage their mental health care as adults. This is key as children reach 16 years of age and may think they don’t need help anymore.

“People stop receiving services because they look around the waiting room and say, ‘I don’t look like that person over there. I don’t need this help,’” she said. “So we have this falling out when they stop losing this care. Our goal is to get them to continue that care to give them strategies for success after high school.”

Further reading

Transforming student writing in the Ozarks

Those are the research questions Dr. Keri Franklin hopes to answer.

Those are the research questions Dr. Keri Franklin hopes to answer.

Franklin’s work has led to the establishment of the Center for Writing in College, Career and Community, an endeavor that seeks to support improving student writing for all students, and especially those teachers and students working in rural schools. This new center is the home to the Ozarks Writing Project.

OWP is supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Education, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the Missouri Department of Higher Education.

Franklin, Missouri State University’s director of assessment and associate professor of English, is the founding director of OWP, which provides professional development to thousands of area teachers across disciplines —such as science, math, social studies, and career technical educators.

“Teachers have expertise to share and few opportunities to share it outside of the classroom,” she said. “The OWP model focuses on bringing teachers together to teach each other and research their own work.”

Over the last decade, Franklin has secured $1.3 million in grants to carry out the organization’s mission: to impact student writing outcomes as well as teachers’ beliefs and practices.

“I love getting community partners together and seeing people achieve and grow. To create a network that could go on without me — that’s bigger than me — I’m really proud of that.”

Measuring student improvement

Franklin’s most recent research study was in partnership with National Writing Project and funded by the Investing in Innovation (i3) grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

Franklin’s most recent research study was in partnership with National Writing Project and funded by the Investing in Innovation (i3) grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

She was one of 12 site directors chosen for the grant, which resulted in more than $600,000 in funding for OWP’s College-Ready Writers Program, a partnership between Missouri State and the Monett, Laquey, Branson and Richland school districts.

The study focused on improving academic writing in grades 7 through 10, supporting rural educators in teaching academic writing, specifically argument writing, and working with school districts to sustain the work beyond the grant period.

The results are promising.

Ultimately, CRWP had a positive, statistically significant effect on the four attributes of student argument writing—content, structure, stance, and conventions—measured by the National Writing Project’s Analytic Writing Continuum for Source-Based Argument. In particular, CRWP students demonstrated greater proficiency in the quality of reasoning and use of evidence in their writing.

Students of a Laquey, Missouri, teacher who participated in that program saw a 17 percent jump in scores on the state test in one year.

“These kinds of gains and partnerships are years in the making, and they are the result of a cadre of teacher-consultants in school districts around southern Missouri who are committed to the teaching of writing,” Franklin said.

Leading the way

OWP began as a satellite site in 2005 with 10 teachers from elementary, middle, high school and community colleges, including Franklin who was pursuing a PhD in English education. In 2008, with multiple support letters from teachers and school districts, OWP became a full National Writing Project site — one of nearly 200 located at universities across the United States.

Since starting at Missouri State, Franklin’s research areas have grown to include the impact of professional development on writing outcomes, digital writing and writing assessment.

While she continues that research, she faces her next challenge head-on: to bring the transformational experience of professional development to teachers in rural and high-needs schools for free.

It is a feat that looks likely for OWP, an organization on the forefront of shaping what the future of writing education will look like in the U.S.

Further reading

Eye to eye or eye for an eye

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

Oyeniyi has spent the last 10 years researching the roots of terrorism in West Africa. Looking at the Latin root “terrorem,” which means to instill great fear or dread, and “terrere,” which means to fill with fear or to frighten, he defined terrorism to include individual, group and state activities.

“The definition is always what others do to us. It’s always going to be a guy or group on the other side of the street,” he said.

Although approximately 50 such agitators or groups exist in West Africa, Oyeniyi has written and presented extensively on Boko Haram, which has garnered much attention from the media since it was assembled in the early 2000s. According to Oyeniyi, this group is easier to study than most since the founder Muhammed Yusuf recorded sermons and distributed them widely in the form of CDs, DVDs and leaflets in the early 2000s.

“There are people who will come out boldly to address the public in the form of open air preaching. What are they agitating for? Their belief system,” Oyeniyi stated.

The initial sermons are contraband now, but founding members of Boko Haram can serve as a lead for Oyeniyi. These ex-members offer insights into what drives the agitators to don the suicide vest. Moreover, these former members also could bridge the gap to begin peaceful negotiations.

As a social historian, Oyeniyi looks for patterns within the movements of specific groups and traces the roots of the conflict. Tracing the trends, he is able to build a profile of what an agitator group looks like and what the likely outcomes could be. He begins to postulate: What are they really fighting for? How are they getting their training? Who are their allies? Who funds them? Then, he and his collaborators create suggestions and form conclusions that the government can work with to address the root of the issue.

As much as possible, I want to see a world where we are all free. Free to express our anger against established institutions and individuals and also free to be corrected. So I long to see a Nigeria that is peaceful. I consider this my own way of contributing to it by exposing what is going on.

Greed versus grievance

Greed versus grievance

What he has to say might shock you. He understands Boko Haram’s complaints.

“They are requesting something, part of which includes the fact that the nation-state is, as it is, not properly governed,” said Oyeniyi. “So they have social grievances, and they have also what I call greed.”

Their grievances are at least, in part, related to a religious struggle as old as time. Two categories of Muslims abound in Nigeria: those who believe the Quran is not open to interpretation and want to see Sharia law enforced as the indisputable law of Nigeria; and those who see the Quran as open for interpretation and therefore welcome innovations, like Western education. In Nigeria, the second category is the majority.

If you eliminate Boko Haram today, you still have 49 other groups to deal with. It should not be about eliminating a group or set of groups, but looking at the causes.

One of the primary reasons behind the formation of the Boko Haram – which means Western education is a taboo – was the removal of innovations from Islam. Since the colonial period, there is no dearth of groups crusading against this, and these groups unite in their belief that other Muslims, especially those in power, are corrupt. Since 2000, Boko Haram has engaged in heated ideological and doctrinal debates with other Muslims, who found the group’s teachings unwelcoming to progress and sought state intervention to rein the group in.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

In addition to ideological disparity, socioeconomic issues like abject poverty, endemic corruption and unemployment are driving Nigerians to desperately rise up against the state. Police brutality and excessive and misuse of military force also contribute to these social grievances, as evidenced by the fact that the initial targets of Boko Haram was the police, not civilians.

“The state itself needs to understand at what point human rights kick in. Boko Haram may be a terrorist group, but they also have fundamental rights that must be respected. We must recognize this if we’re going to fight and win against Boko Haram,” said Oyeniyi. “As things are, the government has failed to realize that dissatisfaction in the eyes of man will almost always force him to take radical actions.”

In summer 2015, Oyeniyi traveled to his homeland of Nigeria to collect documents Boko Haram released before they decided to go underground. Now, he will translate and make them available in the form of a book. By doing so, he hopes to gain further insight into what genuine concerns stand behind the rhetoric.

Taiwan: Where politics, history and geography collide

According to Dr. Dennis Hickey, distinguished professor of political science and director of the graduate program in global studies at Missouri State University, that’s essentially what happened between China and Taiwan in 1949. For decades, Taiwan was recognized as the sole government for all of China, wherein they even held the UN seat for China, until 1971.

The People’s Republic of China (mainland China) and the Republic of China (Taiwan) don’t agree on how this all transpired, and Hickey said this remains the biggest hurdle in Sino-American relations to this day. It’s fascinating and frustrating, and it’s what has driven his research for the past 30 years.

“Taiwan is no longer a dictatorship; it’s a multi-party democracy, which is great for American interests because we support democracy,” said Hickey. “It’s also a potential problem because not everyone agrees that Taiwan should remain as the Republic of China. There are some people who never want to unify with the mainland, which could reignite the Chinese civil war and involve the United States.”

If he could devise a perfect solution for the situation, he’d have them “agree to disagree” and postpone any decision for 50 years.

As an adolescent, Hickey became interested in East Asia: His father, as well as many of his friends’ fathers, had fought the Japanese in World War II, and he watched the Vietnam War unfold on the nightly news.

Policy relevance

Because China is so important– home to more than 1.3 billion people and the world’s second largest economy – Hickey strives for policy relevance in his research to give U.S. officials options to prevent a conflict with China.

He has advised heads of state in Taiwan and in the United States, even testifying before a U.S. Congressional Commission created to monitor America’s relationship with China. His credibility with other academics, the media and government officials rests on the fact that he looks at each issue objectively.

For example, recently he was asked to conduct research on a dispute over several small, uninhabited islands in the East China Sea. He searched documents, interviewed officials, presented his findings and published an article in a top tier journal.

“In the East China Sea, these islands have three different names depending on where you are. They’re really little specks, but there’s oil and gas underneath them. They’re claimed by China, Taiwan and Japan. China and Taiwan both believe that Japan stole these islands during the first Sino-Japanese war in 1895, and they want them back,” said Hickey. The Japanese government formally nationalized the islands in 2012, “sparking the largest anti-Japanese riots in that realm of the world since WWII,” he added.

“Now when I visit Taiwan, I can change planes in Beijing. Why is that a big deal? Well, until recently, you couldn’t get from one side to the other directly because of the political problems. Now, there are millions of tourists from the mainland. They go and take pictures at the presidential palace and the flag. They can’t fly that flag in the mainland.”

Recent improvements

Within Taiwan, there are disagreements about whether Taiwan should be an independent country or remain as the Republic of China. Chen Shui-bian, who served as president from 2000-08, tried to promote independence, and Hickey noted that this movement eventually served to improve relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China.

“I think Chen scared the mainland. That’s when they got a little bit more reasonable instead of just bullying Taiwan,” he said. “They’re talking now, they’ve got direct trade and travel, and they’ve signed 21 major agreements in the last seven years.”

Many times, he collaborates on publications with current and former students who continually offer fresh perspective. In fact, it’s the thought-provoking questions from his graduate students that occasionally inspire his research in the first place.

Agree to disagree

Traveling to and from Asia to be part of this policy discussion for more than three decades, Hickey has established trusting relationships with people on both sides, though he jokes that a little suspicion arises from some mainland Chinese contacts. But are they against his work?

“Not at all. They know I do not support Taiwan independence. There is a Chinese government in Taipei and a Chinese government in Beijing. They are okay with that,” he said.

When he began this research in graduate school, the economic and political systems in both China and Taiwan were quite different.

“The two sides have moved closer economically, but not politically,” he observed. This is the primary reason he thinks the dispute should be shelved for 50 years.

“They should sign a peace agreement and agree to disagree what it means to be China and ratchet down any potential problems,” he said. “It’s their own internal affair. We shouldn’t be pushing them to unify or separate – just don’t let them start World War III.”

Further reading

Broaden your horizons: Consider a master’s in global studies

That rings a bell: Professor studies stars’ vibrations using space telescope

“I remember those very clearly, mostly for how boring they were,” said Reed, professor of astronomy at Missouri State University. “You waited forever for them to have a two-minute video, which was horribly fuzzy.”

Despite the lack of entertainment he seemed to get from watching the landings, they were one of the first things he thought of when deciding what to study in college. The rest, as they say, is history.

The “sounds” of sweet harmony

“Imagine you’re listening to an orchestra. Every instrument has its own set of sounds, and stars are just like that.” — Dr. Michael Reed

With help from funding through NASA and the National Science Foundation (NSF), Reed is currently studying how stars vibrate with help from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft. This space telescope orbits the sun, and in its original mission, observed one set of stars, taking a picture every minute, for four years. Now in its extended mission, it looks at a different set of stars every 90 days, providing the most accurate data ever obtained with accuracies down to one part in a million.

Reed and his team analyze these images to see the stars’ vibrations and discover what is going on inside.

“Imagine you’re listening to an orchestra,” said Reed. “Every instrument has its own set of sounds, and stars are just like that. They have a whole bunch of variations within them, and each of those variations tells you something about a different region inside of the star.”

Reed then classifies the different vibrations, or instruments, coming from the star. But how does learning about these vibrations help us here on Earth?

“These are stars that our sun will be like in another five billion years,” said Reed. “By understanding these stars, we can understand what’s going to happen to our solar system and the environment of our solar neighborhood in the far future.”

Getting good vibrations from Kepler

Kepler was launched in March 2009 with a mission to discover new planets over a four year time frame. The telescope was able to discover these planets when they passed in front of stars, causing a light blockage known as the transit. Unfortunately, researchers cannot tell how big a planet is unless they know how big the star is. That’s where Reed’s research comes in.

“Only in the cases that the star is pulsating, known as a variable star, do they know the size of the star because asteroseismology tells you that based on its vibrations,” said Reed. “That, in turn, gives you the size of the planet.”

Researchers, such as Reed, who are outside of NASA, are able to apply for observations during Kepler’s extended mission. In other words, an astronomer can ask NASA, “Could you focus on this star for a while?” So far, Reed’s observing programs have been approved during each extended campaign.

A game changer

“In the big picture, nothing has advanced asteroseismology as much as Kepler….” — Dr. Michael Reed

Over the last 10 years, Reed has received more than $1.2 million in funding to advance his research. His collaborative team has published more than 15 papers where they have unveiled differences in the chemical stratification within these stars, discovered stars with close companions, and even one which spins more slowly in the center than at the surface.

“In the big picture, nothing has advanced asteroseismology as much as Kepler, quite frankly,” said Reed. “Our knowledge of the insides of stars has really gained huge ground from this spacecraft. Observing in that way has profoundly changed our view of the universe.”

Reed’s collaborative team, which consists of fellow professors, graduate and undergraduate students, received their most recent transmission of data in July 2015. The team will process and analyze these data, possibly helping the science community learn more about helium fusion, planets outside our solar system and our solar neighborhood as a whole.

Further reading

Recording history to save it

A famous wreck is the steamboat Arabia that sank in 1856.

“They had everything from shoes and boots – there were 4,000 of them – all sorts of sets of dishes, kegs of different size nails, picks, any kind of tool,” said Dr. Neal Lopinot. “Really it was a steamboat full of merchandise that was going out to the frontier. Some of it was nice stuff, too, but most of it was utilitarian.”

Lopinot is a research archaeologist and director of Missouri State University’s Center for Archaeological Research, or CAR. Ensuring that such remains are not destroyed is one of the many projects that keep the doors open at CAR.

The center is a research institute that conducts archaeological field work and other cultural resource management projects on a contractual basis, primarily for government agencies.

The excavation team makes progress at the Oklahoma dig site. They planned to go down to about 3.1 meters, and stand about 1.6 meters deep.

Preserving steamboat wrecks

Since 2012, CAR has been employed to survey several former islands along the Missouri River where the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and Army Corps of Engineers wanted to dig trenches to recreate spawning grounds for the endangered pallid sturgeon.

“They’ve lost their primary spawning grounds so the population’s diminished; they’re trying to recreate that,” said Lopinot. “Not just for the pallid sturgeon, but that was the main focus of it; but there are lots of other fish that also spawn in those kinds of situations. Also it increases wildlife habitat, wetlands.”

Before the trenches were dug, Lopinot and a team of researchers from CAR used magnetometry to see if there were any steamboat wrecks in those areas. They found the remains of at least one boat.

Dr. Neal Lopinot and Jack ray examine an artifact

“They decided to move the trench to avoid impacting the buried steamboat wreck,” he said. “Just about every steamboat wreck is considered to be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, which means they’d probably have to mitigate it, which in turn means a major and very costly excavation.”

Lopinot is the primary person writing proposals and responding to requests from agencies that want to hire a group to undertake archaeological surveys and excavations. The center raises an average of about $250,000-300,000 a year in grants and contracts.

Many of CAR’s projects are work that is required by the National Historic Preservation Act. The search for steamboat remains was based on Section 106 – it involves finding out if there are any significant archaeological remains in a specific area before any work is done that might disturb the remains.

Another type of research is based on Section 110 – documenting and preserving archaeological sites. CAR has recently been involved in Section 110 research at the Three Finger Bay site on the Gibson Reservoir in northeast Oklahoma. Prior studies have found archaeological remains on a finger of land extending into the reservoir. CAR researchers have been excavating a section to determine the significance of the site.

The center has been involved in a number of prominent archaeological studies including Big Eddy, Delaware Town and the Trail of Tears.

Dr. Lopinot and his team digging at the excavation site in Oklahoma

Digging in the dirt

On a beautiful fall day in the Ozarks, Lopinot spent the day digging in the dirt – one of his favorite parts of his job. Along with CAR Project Supervisor Dustin Thompson and three other archaeologists (including two MSU alums), the team methodically skimmed dirt from an excavation area and then sifted through the dirt to find any artifacts.

On that day, the main part of the excavations was down about 1.6 meters deep and they planned to go down to 3.1 meters.

“It looks like the site was intensively occupied during what we call the Middle Woodland Period – about 100 BC to AD 400. There are other periods represented as well,” said Lopinot. “We’re going to dig a lot deeper, and we’re hoping that we find much earlier deposits that are relatively un-mixed. Hopefully there’ll be a little charcoal that we can radiocarbon date.”

“It looks like the site was intensively occupied during what we call the Middle Woodland Period – about 100 BC to AD 400. There are other periods represented as well,” said Lopinot. “We’re going to dig a lot deeper, and we’re hoping that we find much earlier deposits that are relatively un-mixed. Hopefully there’ll be a little charcoal that we can radiocarbon date.”

Stone artifacts cannot be dated because the method requires carbon from formerly living plants and animals. At this site, they have been looking for plant remains such as hickory nutshell fragments or wood that has been carbonized. Bones and shells can also be dated because they are also from once-living animals. In dating stone artifacts, for example, an archaeologist tries to find dateable materials as close vertically and horizontally to those artifacts, documenting the precise location of each.

Lopinot and Jack Ray, CAR assistant director and research archaeologist, recently had some of their research from the Big Eddy site near Stockton, Missouri, published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” and Lopinot was the principal author of an article published on the construction of Monks Mound, the largest mound at the largest site in North America, in the “Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology.”

Lopinot and Jack Ray, CAR assistant director and research archaeologist, recently had some of their research from the Big Eddy site near Stockton, Missouri, published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” and Lopinot was the principal author of an article published on the construction of Monks Mound, the largest mound at the largest site in North America, in the “Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology.”

Hands-on guy wants to re-democratize society

“It had a tremendous impact on the way that I viewed things, like differences in educational opportunities and outcomes,” said Stout. “It taught me a lot how just by virtue of the family I was born into and the community and neighborhood that I lived in, how I had certain advantages and opportunities growing up that a large number of people didn’t have.”

“In terms of my background, I really became interested in the progress of education and how we have a systemic issue that reproduces class and racial inequalities in our society.” — Dr. Mike Stout

Stout’s parents, a pharmacist and a nurse, inspired him to go into a career helping others. Instead of entering a health field as he originally intended, though, he has become an instrument for change by helping groups of people have a voice that ordinarily feel isolated or underrepresented.

He’s a pioneer in the research of social capital – the concept that some resources are accessed more readily through connections and trust with other individuals. Throughout his career, he has repeatedly seen that a more diverse group of social connections – including friends, neighbors and colleagues from a variety of backgrounds – opens up more opportunities and encourages feelings of efficacy for all involved.

He’s a pioneer in the research of social capital – the concept that some resources are accessed more readily through connections and trust with other individuals. Throughout his career, he has repeatedly seen that a more diverse group of social connections – including friends, neighbors and colleagues from a variety of backgrounds – opens up more opportunities and encourages feelings of efficacy for all involved.

“College made me realize I was much more interested in political, social and economic forces in society and how those limit opportunities,” he said. “To be honest, if I would have gone to another undergraduate university that wasn’t located in a major city in the middle of kind of a big ghetto, I probably would have ended up continuing on with my med studies or getting into finance. Something that pays a little bit better than what I’m doing right now.”

Checking out Missourians’ civic health

Since 2010, a primary focus of research for Stout has been the production of the statewide Civic Health Index (the second was released in 2013, with another scheduled in 2015). This study looked at levels of participation in public forums, volunteer opportunities, neighborhood collaboration, voter registration, voter turnout and involvement in non-electoral political activities. These factors reveal a picture of how engaged citizens are in their communities and how much they invest in making their communities better.

“My work involves taking the expertise of faculty members, including myself, on campus and using it to provide information for local leaders, citizens and other stakeholders in the community to make better decisions about how we can collectively self-govern and increase democratic practice in community problem solving.” — Dr. Stout

To fulfill Stout’s goal of building a network of scholars and decision makers who advocate for collectively addressing community problems, he collaborated with scholars and practitioners from five other Missouri universities and Missouri Campus Compact for the 2013 report.

“What the Civic Health Index is examining is the health of the nonprofit sector – sometimes called civil society – and it shows us that the private, public and nonprofit sectors don’t operate in isolation. How our community is doing influences how representative our politics are. How our economic institutions are functioning determines how stable our communities are. How our economic sector influences our political sector determines the resources that flow through civil society, versus flowing through the private sector, and so on.”

Stout, working along with the National Conference on Citizenship, has served as the main facilitator on this massive undertaking. It’s no big deal – he’s been busy his whole life, he laughed.

Stout, working along with the National Conference on Citizenship, has served as the main facilitator on this massive undertaking. It’s no big deal – he’s been busy his whole life, he laughed.

But one of the weaknesses of the report (scheduled to be released in September 2015 with analysis being conducted by the Center for Information on Civic Learning and Education (CIRCLE) at Tufts University) is that the data is collected at a national level and then filtered down to the state level.

“You really can’t – other than at the state level – dig down into what’s actually happening in different parts of the state, which limits the practical application of using this to inform policy.”

To make it more representative of what is occurring in individual communities, Stout designed a strategy to have the 19 local councils of governments in Missouri administer a version of the survey to its constituents. He’s certain that the results will be more meaningful to economic development specialists and policy makers in some of the less populated, more rural areas of the state.

‘I want to re-democratize our society’

He’s a hands-on type of guy, and he works hard to empower people often through grass roots efforts. In fact, one of his first jobs was as a phonics tutor to underrepresented minority children in Philadelphia.

Now, he teaches statistics and craves data that will back up his hypotheses. He knows it’s one of the ways that he can gather support across party lines on potential policy changes.

“The idea here is to really use data as a basis for beginning discussions in communities so that people are starting with the same assumptions,” he said. “Partisanship has become pretty bad in our society. But one area where liberals, conservatives, Republicans and Democrats do agree is that people should be empowered and have a voice in the direction of their own lives.”

In 2010, Dr. Stout and several collaborators initiated the Ozarks Regional Social Capital Study to examine social capital and citizen participation in southwest Missouri. They found that people in the region tend to have many interpersonal connections, high levels of participation in voluntary groups (especially faith-based organizations) and high levels of trust in others. However, they also found that in the Ozarks there are relatively lower levels of civic engagement compared to the national average. “It’s influenced the way people talk about issues in the local community, has led – indirectly and directly – to new positions and resources in city government, and has highlighted civic engagement as a one of the four themes tying the 13 chapters of the city’s long range strategic plan together.”

‘No safe place for kids to play? Not a place to stay’

Feeling safe and valued starts at home, and in 2011, the Community Partnership of the Ozarks in Springfield, Missouri, joined a network of four other communities nationwide in establishing the Neighbor for Neighbor project. This initiative, supported by the Kettering Foundation and Everyday Democracy, is a community effort to minimize economic challenges by letting individual citizens voice concerns about a neighborhood and making positive changes. Currently, approximately 25 local community partners are involved to facilitate dialogues and find resources that these two poverty stricken neighborhoods can tap into to address issues like safety.

“We’re setting up opportunities for underrepresented groups to be involved in the community dialogue – it’s part of the Dialogue to Change program – about the best ways to frame and address problems. That is something everyone can get behind because it’s about empowering communities. It’s about empowering people. It’s about democratizing the community problem-solving process.”

At its core, Neighbor for Neighbor, which Stout now helps to facilitate, brings people together to learn more about their neighbors and build trust – something Stout found through surveys of Springfield residents that is disproportionately low among the individuals in these particular neighborhoods. The neighbors who participate in the program talk about the issues plaguing their neighborhoods and are shown the resources at their disposal in order to make their neighborhoods feel safer – whether it be adding street lighting, building community gardens or cultivating green space for a park.

At its core, Neighbor for Neighbor, which Stout now helps to facilitate, brings people together to learn more about their neighbors and build trust – something Stout found through surveys of Springfield residents that is disproportionately low among the individuals in these particular neighborhoods. The neighbors who participate in the program talk about the issues plaguing their neighborhoods and are shown the resources at their disposal in order to make their neighborhoods feel safer – whether it be adding street lighting, building community gardens or cultivating green space for a park.

Although Neighbor for Neighbor has gained some footing, it’s a tough sell, noted Stout. The individuals in the neighborhoods are transient, so they typically don’t stay involved long. They also feel quite alienated from community leaders and socially isolated.

“Even if they wanted to get involved, they often don’t see the point because they don’t think it would make a difference. They also have the least diverse connections to social economic organizations and individuals,” he said. “It turns out, that those are significant obstacles to getting people involved in initiatives where we want to empower people.”

Mapping conflict

One of Stout’s earliest studies in the field of sociology further influenced his career path. Stout, an undergraduate student at the time, collaborated with a graduate student at Temple University to study 10 years of data on reported hate crimes in Philadelphia. They then geo-coded each incident to see how the crimes were dispersed geographically.

“What we found is the areas with the highest amount of racial and ethnic conflict were happening on these border lines where white neighborhoods meet black neighborhoods and where Jewish neighborhoods meet working class white neighborhoods,” he said. “That got me really interested in kind of the social structure of conflict and how this related to housing, segregation and all of these other things.”

The data was originally collected by the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, and his report was later distributed to elected officials and other civic leaders in Philadelphia, which pleased a young Stout. It also helped to solidify in him that one goal in sociological study should be to influence policy changes.

Another outcome of this study still creeps up and interferes with the momentum he tries to make with the Neighbor for Neighbor initiative to this day.

“People who try to get ahead and move out of those bad situations or into better situations are often faced with prejudice and discrimination and all of these things that are kind of beyond their control,” he said.

‘It’s very serendipitous the way that it worked out for me’

When Stout was looking for a position in the academic world, he wanted to find a place where he could make a difference. At the same time, Missouri State’s sociology department was shifting from a more traditional, academic sociology program to what is termed a public sociology program, where students take the classroom theories out into the community and get involved in issues they care about. The first step to that transition was incorporating community based research and engaged scholarship into the tenure promotion guidelines, which allowed Stout to teach and get involved.

He got so involved, that in fall 2014, Missouri State University’s Center for Community Engagement was established and Stout was named its first director. In a short time, he has made huge strides on building partnerships for the Center, securing funding and gaining momentum behind projects and studies that will be done – all for the greater good.

He got so involved, that in fall 2014, Missouri State University’s Center for Community Engagement was established and Stout was named its first director. In a short time, he has made huge strides on building partnerships for the Center, securing funding and gaining momentum behind projects and studies that will be done – all for the greater good.

“The Center for Community Engagement here at Missouri State is the first such partner of the National Conference on Citizenship in the country. What I’m really trying to do is – locally, regionally, statewide and nationally – weave Missouri State as one of the central nodes for research and practice on social capital and civic engagement in the country. That’s kind of the bigger goal.”

After Dr. Stout completed his dissertation, Racial and Social Economic Inequality and Political Participation, he decided to expand beyond electoral politics. He realized that so many decisions and agents of change happen outside of the scope of elections.

After Dr. Stout completed his dissertation, Racial and Social Economic Inequality and Political Participation, he decided to expand beyond electoral politics. He realized that so many decisions and agents of change happen outside of the scope of elections.

The big questions: Life and death in the Middle East

The opportunity to examine such questions drew his attention to the Middle East and ultimately to Kurdish communities in the region.

Romano, who holds the Thomas G. Strong Chair for Middle Eastern Studies in the political science department, has written two books tackling life-and-death questions that affect Kurds in Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey. He also dissects everything from Iranian nuclear negotiations to American influence on the Iraqi constitution in his column for the Kurdish newspaper “Rudaw.”

“It doesn’t even occur to me not to be impassioned about it.…I may have met the people in question.” — Dr. David Romano

When asked how he musters fresh concern for a region whose complexity and violence drive many to bitter resignation, Romano said, “It doesn’t even occur to me not to be impassioned about it.” On reading about 200 Assyrians captured by the Islamic State, he reflected, “Their village is on the banks of the Khabur River. I’ve swum in that river. I know exactly where it is. I may have met the people in question.”

Interrupting radicalization

Romano’s tactile understanding of the Middle East and network of connections – both products of his extensive travel – are great assets to his current research, a global comparison of the factors that contribute to extremism.

The cross-case study of radical groups in Europe, Latin America and Asia seeks answers to one of today’s most anxiety-inducing questions: Why would someone be willing to take up arms for a cause?

“In the research, that person could be anyone,” Romano said, “depending on the context and the socialization that occurs.” However, he noted, “I don’t subscribe to this idea that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter.” Accordingly, the study focuses on groups that use radical tactics rather than assessing whether their goals are radical.

“In the research, that person could be anyone,” Romano said, “depending on the context and the socialization that occurs.” However, he noted, “I don’t subscribe to this idea that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter.” Accordingly, the study focuses on groups that use radical tactics rather than assessing whether their goals are radical.

“For the purposes of this analysis, it’s the means they are willing to resort to that define whether someone’s a terrorist. Someone struggling for a clean environment for poor people will be a terrorist if they set bombs against civilians in order to accomplish it. ”

Over the course of the project, an international team of collaborators will examine some of radicalism’s most commonly cited factors, including the insertion of religious interpretations into politics, a lack of democracy, a history of colonialism and extreme poverty.

Across radical groups, youth appears to offer a critical window. “That’s when people become politically aware,” Romano said. In addition, young people are strongly influenced by peer groups, and the rise of social media has created new platforms for dangerous ideologies. According to Romano, “We’re seeing this remarkable phenomenon of the Islamic State recruiting people via Facebook.”

Engaging students at Missouri State

Yet while youth can make someone vulnerable to destructive ideas, it also marks a time of openness and growth. Romano’s scholarship has roots in his own undergraduate days, when he tagged along on a friend’s trip to Turkey. There – in the midst of a Kurdish insurgency – he found that “half the people were telling me Kurds didn’t exist in the country, and others were telling me they were fighting for their rights. Others said they were terrorists. I got really curious as to what the situation was.” A lack of Western scholarship on the issue prompted his first investigation into Kurdish identity, ideals and culture.

“Engaging students to approach issues objectively and ethically goes a long way toward fulfilling the public affairs mission [of Missouri State].” — Dr. David Romano

Now, Romano provides similarly enriching experiences for his students, including study abroad courses and multicultural interactions – such as a celebration of the Kurdish holiday Newroz that he hosts each spring.

Now, Romano provides similarly enriching experiences for his students, including study abroad courses and multicultural interactions – such as a celebration of the Kurdish holiday Newroz that he hosts each spring.

“Engaging students to approach issues objectively and ethically goes a long way toward fulfilling the public affairs mission [of Missouri State],” he said. “When they walk out of here, they may not remember the details of dates or events, but hopefully I’ve instilled in them a way of approaching these questions… to make them better citizens. So that if someone from another ethnic or religious group moves next door to them, they will have the curiosity and background knowledge to understand them, which makes for a better society.”

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.

Although you identify yourself as the head of a household, now you are the recipient of care. Your spouse or child has assumed the role of care-provider, which may be a new role as well. The relationships in your family are feeling unbalanced because the power status has changed.