The indigenous peoples of the Andean region of South America are master textile makers, with an ancient history of creating textiles that spans millennia. The Andeans developed an ingeniously simple but highly flexible, portable type of loom known as the backstrap loom, which allowed weavers to bring their work with them and to practice their techniques virtually anywhere.

In recent years, Andeans have adopted imported threads and dyes, and more efficient types of weaving and decoration have developed for the tourist-trade, as these are more financially lucrative. Nevertheless, Andean weavers continue to value and to pass down their traditional tools and techniques from mother to daughter, preserving and taking pride in their cultural traditions.

Otavalo culture

20th century

Cotton, wool, and pigment, L. 34 cm x W. 4 mm x H. 39.2 cm

BFPC collection #2016.24

This 20th-century pillowcase incorporates panels that use a traditional method of decoration known as ikat. Ikat involves intricately bundling and tightly tying individual groups of threads, and then dying the threads in different colors. When the threads are untied, some areas retain the original color of the thread. Skilled ikat dyers use this technique to create geometric patterns as well as images of animals, plants, and humans; when the threads are woven into cloth, they create softened but identifiable designs. The ikat panels on this pillow illustrate profile images of snails with spiral shells as well as a birds-eye view of swimming turtles.

Otavalo culture

20th century

Wool and pigment, L. 51.8 cm x W. 1.7 mm x H. 50.5 cm

BFPC collection #2012.38

This heavy, woolen bag is strong and sturdy, and it was therefore likely made for everyday practical purposes such as carrying goods. Although bags were made and used in the Andes since ancient times, traditionally indigenous women wore shawls that were used to carry everything from goods to children; however, in the 20th century both men women began using shawls and carrying cloths less and less, instead making and using bags of many different types.

On the front of this bag is an image of a Catholic church with a central chapel and two bell towers, each topped with crosses. As the majority of Ecuadorians, including the indigenous cultures, practice Roman Catholicism, and church architecture is often a point of pride in communities, this would not have been an unusual motif for an everyday item. Interestingly, however, when the opening of this bag is on the top, the church rests upon its side.

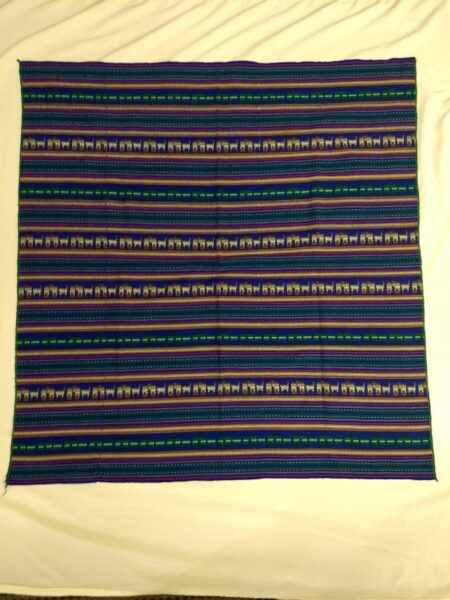

Bolivian Mestizo culture

Late 20th century (ca. 1980’s)

Cotton and pigment, L. 1.16 m x W. 2 mm x H. 1.20 m

BFPC collection #2014.41

Awayos, also known as llikillas, are brightly colored panels of cloth that traditionally have been used as practical carry-all devices for everything from children to firewood. In Bolivia where this was produced, awayos are part of indigenous women’s traditional attire, but they are also used in rituals involving rites of passage.

The designs on awayos typically are rendered in a rainbow of colors with a variety of different patterns and motifs, and these textiles literally symbolize the rainbow, which is a symbol of good fortune. Today, like many shawl-like textiles, awayos are being replaced by bags as practical carrying devices, but their bright, colorful designs ensure that they remain popular as part of traditional costume and as items made for the tourist trade.

Peruvian Mestizo culture

20th century

Cotton, wool, embroidery thread, and pigment, L. 49 cm x W. 5 mm x H. 83.4 cm

BFPC collection #2012.54

This decorative, tourist-trade wall-hanging takes the form of a tapestry illustrated with a Sicán-style tumi knife motif. The tumi knife is a highly symbolic implement that was developed among the earliest cultures of the Andes; it was used for ritual sacrifice, and it is identifiable by its sharp, half-circle blade. Later Andean cultures each created their own version of the tumi knife. The Sicán cultures of northern Peru developed one of the most celebrated and highly recognizable versions of the knife: They topped the semicircular blade with the face or the full figure of the Sicán deity, a supernatural character identified by its teardrop-shaped eyes and its huge, half-circle headdress.

Quechua Mestizo culture

20th century

Wool and pigment, L. 45.8 cm x W. 2.5 cm x H. 72 cm

Hernandez collection #2012.18

The Andean bag known as a chuspa is a handmade carrying bag that traditionally was used to store coca leaves. In its leaf form, coca is a relatively mild stimulant that ancient Andean peoples chewed to stave off hunger and to provide stamina, especially while traveling in the thin oxygen if the high Andean Mountains. The coca leaves are gathered three or four times each year and stored in chuspa bags made of alpaca or llama wool.

The condition and form of this bag indicates that it was made in the 20th century, but the style resembles the textiles of the ancient Chancay culture (1000-1460 CE), who often incorporated decorative strips of images into their textiles. Along two of the decorative reinforcement strips on this bag are images of running animals that resemble horses, which were introduced after contact with the Spanish, and these strips flank a central strip with standing images of large and small birds, which are well-known motifs in ancient Andean art. The Quechua Mestizo (mixed Hispanic and indigenous cultures) artisan who created this bag therefore may have been paying homage both to her Spanish and her native heritage.

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu