The colorful textiles featured in this exhibit are known as molas, which are artworks designed and produced by female artists of the Guna culture (also known as the Cuna or Kuna culture) of Panama. A mola is a rectangular panel of cloth that is decorated using a reverse appliqué technique: Two to six layers of different-colored fabric are stacked one on top of the other, and the designs are created by cutting through the layers and then turning under the edges of each layer and sewing it down, so that the different colors of cloth form concentric outlines around the shapes of the images that are portrayed as well as backgrounds of colorful shapes.

Molas are created as a pair of panels that will form the front and back of a traditional Guna woman’s blouse. While these two panels tend to have very similar motifs, they are intentionally made with differences and are never made to be exactly the same. Smaller versions of molas, known as molitas, have been developed to sell in the tourist trade, and they are sometimes used to embellish articles of clothing for children; today, reverse appliqué details also embellish the collars, belts, and other clothing for all members of a Guna family.

Guna textile artists began making molas in the 19th century, when contact with and colonization by Europeans encouraged Guna women to wear blouses rather than their traditional garb, which consisted simply of painted loincloths and body paint. While early molas had geometric designs reminiscent of the loincloth painting, the importation of colorful cotton textiles into Panama inspired Guna women’s creativity and the development of the reverse appliqué technique. In 1908, however, the Panamanian government tried to assimilate the Guna into European-Panamanian culture by prohibiting traditional native dress, including a ban on molas. Guna women rebelled against this prohibition and wore their molas in public to show their resistance, and in return they were beaten and jailed. Finally, in 1925, the Guna negotiated a treaty with the Panamanian government to become a sovereign nation, and Guna women today continue to wear molas as a symbol of national pride and identity.

Later in the 20th century, molas became popular in the tourist trade, and today the traditional making of molas has become the most important commodity of the Guna economy. Most often the women artists sell molas directly to tourists, but the opportunity to sell molas abroad has led some artists to sell their works to middlemen; in response, some Guna have formed cooperatives to promote molas on the international market and to ensure that artists receive fair prices for their work. Today the production of molas for the tourist trade serves both as a strong means of financial support for the Guna and as a way to ensure endurance of their cultural artforms and traditions.

Guna culture

21st century

Cotton and pigment, L. 31.9 cm x W. 1 mm x H. 17 cm

BFPC collection #2011.4

Panama is a country with a strong culture of coastal fishing, and fishing often serves as the main source of subsistence for most indigenous groups. As Guna artists often draw inspiration from the native flora and fauna of Panama, fish and other sea life are common imagery in mola art. The Black Mola with Green Fish on Multicolored Stripes is unusual, however, in its interesting portrayal of a fish that is turning its head back toward the viewer. Researched by Kylei Giles

Guna culture

21st century

Cotton and pigment, L. 44 cm x W. 3 mm x H. 41 cm

BFPC collection #2014.32

As turtles are native to Panama, they are often selected as motifs for molas. Perhaps more interesting about the Maroon Mola with Four Small Turtles is that, unlike most molas sold in the tourist trade, this mola had clearly served as decoration on a woman’s traditional Guna blouse before it was sold. This is evident in the scraps of floral blue fabric that are still attached to the top, bottom, and sides of the mola, along with the strip of black fabric with orange rickrack that is still attached to the top. Researched by Kylei Giles

Guna culture

Early 21st century

Cotton and pigment, L. 21.3 cm x W. 3 mm x H. 19.5 cm

BFPC collection #2014.29

Guna culture

Early 21st century

Cotton pigment, L. 20 cm x W. 3 mm x H. 19 cm

BFPC collection #2014.30

The Blue-Outlined Black Frog on Red Molita and the Black Molita with Two Chickens are good examples of small molas, also known as molitas or mola squares, which are often made specifically for the tourist trade and sold as souvenirs. Molitas typically have fewer layers than molas, and the designs tend to be simplified. They also tend to use methods other than reverse appliqué for details and decoration, as illustrated in these two molitas; most of their colorful imagery is formed with embroidery and with the appliqué of small patches of cloth on top of the main motifs. Researched by Kylei Giles and Brianna Shatto

Guna culture

21st century

Cotton and pigment, L. 19.3 cm x W. 1 mm x H. 17 cm

BFPC collection #2016.38

In addition to being produced as souvenirs for the tourist trade, molitas are also often made by Guna girls, who are typically trained from a young age in how to create molas. The simplified, stylized cat motif, the limited number of colored lozenges within the body, and the simple pink and yellow embroidered stitches on the head of the cat in this mola suggest that this was the work of a child; however, the clear, even outline of yellow around the cat indicate that this young artist was quickly learning the complexities of the artform. Researched by Kylei Giles

Guna culture

20th century

Cotton, polyester, and pigment,

L. 46.5 cm x W. 2 mm x H. 37.5 cm

BFPC collection #2016.7

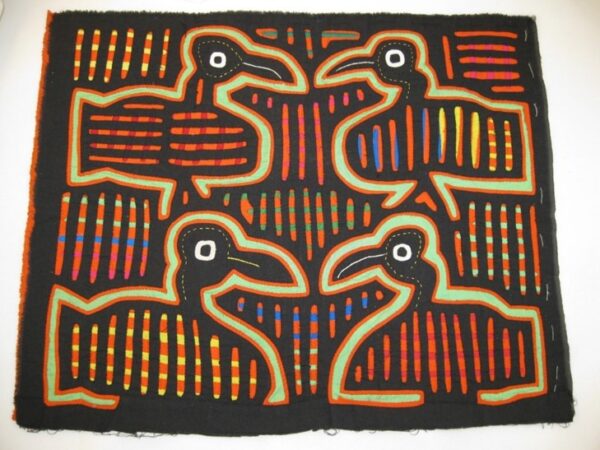

Although molas are made with imported cloth and thread, and their imagery is sometimes inspired by foreign influences, their artistic production of molas is a Guna culture creation. The Large Black Mola with Four Birds is a particularly intricate work that actually consists of two molas: On the top is a depiction of four birds with lozenges of color both inside their bodies and filling the background, but underneath this layer is another mola consisting of a pattern colorful, elongated lozenges, most of which have been turned perpendicular to the top layer. Together, these two layers create a dazzling complexity of color on the black background.

Beautifully made molas like this are especially meaningful, as they are used to mark nearly every major point in a Guna woman’s life. A mola is made for a young girl when she is born, and she starts making molas for herself during her grade school years. The adolescent girl is given a beautiful mola for her “coming out” celebration, as a rite of passage into adulthood, and another is gifted to her when she marries. A special mola is also made upon the death of a Guna woman; if she dies young, the mola is given to her daughters, but if she lives to old age, the mola is buried with her. Researched by Melissa Payte

For more information, you may contact the researcher(s) noted in the title of this exhibit entry, or Dr. Billie Follensbee, the professor of the course, at BillieFollensbee@MissouriState.edu