Archive for 2019

Unveiling the mysteries of the Catholic Church

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman, associate professor of sociology, studies organizational leadership. For much of her career, she has focused on religious organizations, but she doesn’t want to be typecast. She wants to branch out to research nonprofit organizations and leadership more broadly.

But the controversies and the questions brought forth by the church bring her back.

She is a Catholic nun. One of the ways she gives back to the church is to add to the knowledge base of Catholicism. She’s partnered on six publications with several more in progress. She’s presented more than 40 times on topics like the intersection of moral issues and political mobilization in a congregation, and leadership in nonprofit and religious organizations.

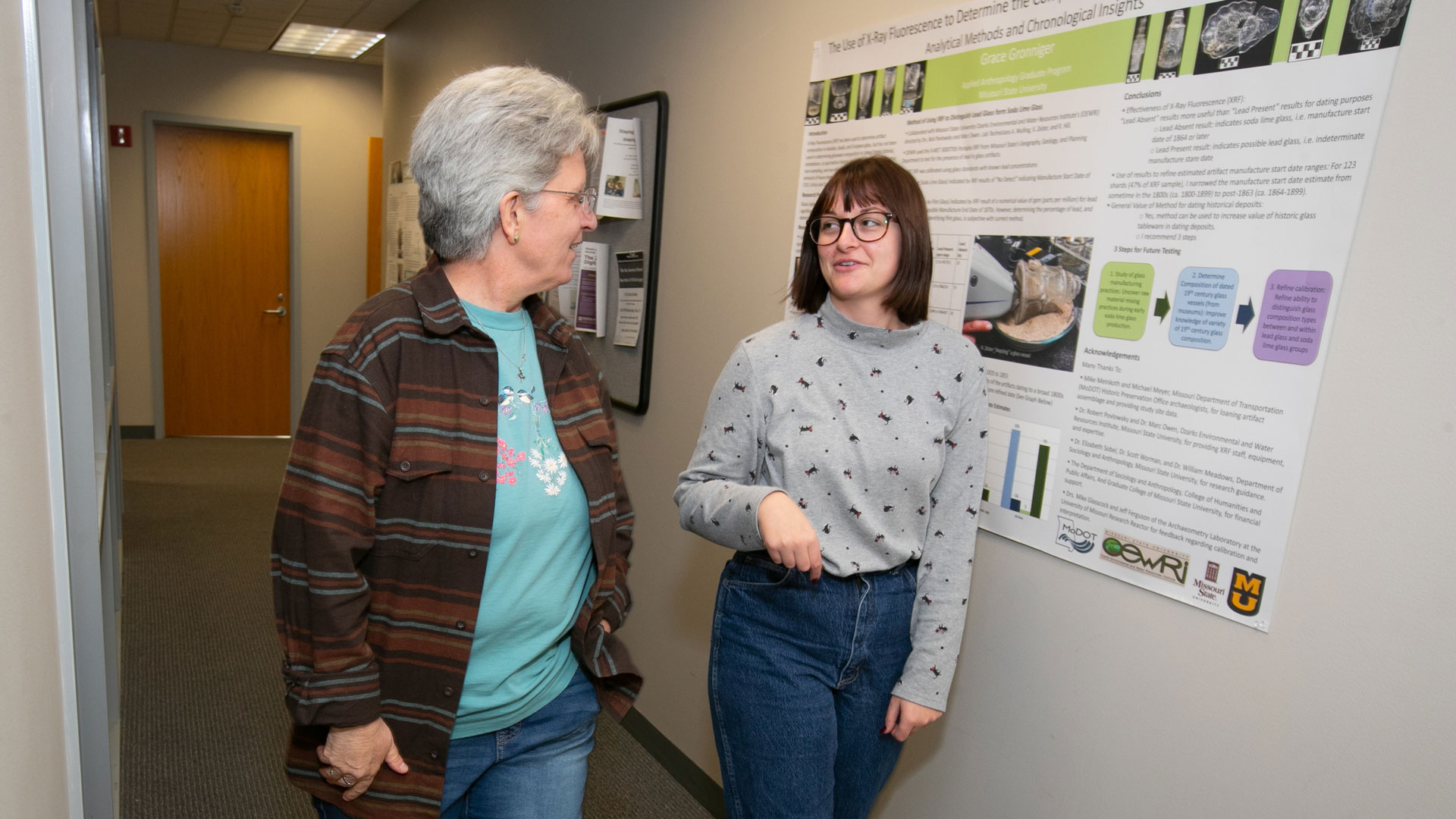

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman meets with student Erica Houston in her office in Strong Hall.

In January 2019, “Catholic Bishops in the United States: Church Leadership in the Third Millennium,” was published. This book was a collaboration between Hoegeman and Drs. Stephen Fichter, Thomas Gaunt and Paul Perl from the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate.

I sort through the data and see what emerges and what’s interesting.

The team reached out to survey more than 400 bishops in the U.S. They were pleased by a 70% response rate.

Being a bishop

With this robust survey response, they developed a narrative. This book serves as a unique and comprehensive view of life as a bishop.

It addresses the demographic makeup of bishops. It also answers questions about daily routines, job satisfaction, leadership style and opinions on hot topics.

In her previous research, Hoegeman explored whether bishops’ liberal or conservative theological orientation influenced decision making. For example, would the bishop use lay people to lead parishes in the absences of priests? Hoegeman found that liberal bishops were more lenient on issues like this. However, the terms conservative and liberal don’t follow traditional political party lines.

“You can’t vote Catholic along party lines,” Hoegeman said. “Catholic teachings are morally conservative and socially progressive.” She ticks off the hot button issues and sympathetic causes for Catholics. “It’s very complex.”

Dissecting the diocese

Her next project, a book unveiling the intricacies of the diocese, will have similarly rich data. And Dr. Gary Adler, a colleague from Pennsylvania State University, appreciates her commitment to diving deep into the data to tell the story.

“Katie connects theoretical ideas and sophisticated methods to her research,” Adler said. “This willingness of hers to fully embody the profession, no matter the circumstance, is a gift.”

She’s mined information that was collected regularly during the last 40 years. One of the primary concerns for her is whether the Catholic Church can be dynamic enough to meet the changing needs of its followers.

Katie’s research on numerous dimensions of congregations — from gender, to social activism, to vitality — has significantly contributed to the field. – Dr. Gary Adler

The greatest concentration of Catholics in the U.S. has historically been split between the Northeast and Midwest. Each area accounted for about 35% of the Catholic population. In the last five to 10 years, greater numbers are showing up in the South and West.

In a religion with less organizational hierarchy, churches would begin popping up. But the Catholic Church, notes Hoegeman, has less agility because of the structure and personnel involved.

You can say, ‘I have my own religion.’ But from a sociological perspective, it’s a group phenomenon.

“What you get are these small, empty parishes in the Northeast and places like Las Vegas – with a booming population – with relatively few, huge parishes,” she said.

Upon closer examination, some of the diocese within New York are still growing exponentially. Why?

“I’m going from the ground up to look at this shift. Part of the story is about immigration and part is related to organizational decline,’” like the closings of Catholic parishes, hospitals and schools, she said.

It will come down to organizational leadership, something Hoegeman knows a lot about, to weather these changes.

A nun’s mission

As she delves into her research or heads into work, the mission of her community of Sisters is never far from her mind.

“My order’s particular emphasis is uniting people, looking for people at the margins,” she said.

To this end, she spends hours with struggling students, making herself available.

Dr. Catherine Hoegeman strolls the office corridor with student Veronica Jacobs.

“My purpose is to bring unity and to level the field. I believe through mentorship, I’m making myself and education accessible.”

And with her research, she is bringing greater understanding to the church she is committed to.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Empowerment through performance

Dr. Jason Hausback, associate professor of music at Missouri State University, was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder in high school. But after learning to manage it, he finds performance empowering.

“I’d rather play a trombone recital for 1,000 people than speak in front of three,” Hausback said.

He was introduced to the trombone in the fourth grade. He liked the kinesthetic feel of the slide and has stuck with it ever since.

“I play melodies by ear in all 12 keys,” Hausback said. “The focus of attention is crucial in performance – both in terms of being a better artist, but also in terms of managing anxiety.”

Dr. Jason Hausback practices in Ellis Hall alongside Dr. Justin Cook.

He has performed in many high-stakes situations. He’s performed with a group on a Grammy-nominated album. He’s been selected to play alongside living legends in the International Trombone Festival.

And since coming to Missouri State, he’s performed 35 recitals around the country with pianists and other musicians.

“Performance is like creating a sculpture,” Hausback said. “Once it’s there, you can’t take it back or improve it.”

He likens it to Olympians training for the games: Despite intense preparation, perfection isn’t guaranteed.

“You spend hundreds or thousands of hours trying to be precise,” he said.

But every time you are on stage, there’s an element of uncertainty. On top of that, you never know how the audience will react.

Talent on tour

One of the most enjoyable parts of his career is the ability to play with other talented musicians. In February 2019, he completed a tour of recitals along the Missouri River with Dr. Nataliya Sukhina, a pianist from Texas Tech. It was the second time he and Sukhina toured with the recital, Darkness and Light.

“The musical selections were all about characterizing how music depicts darkness and light in the western world over time,” he said.

Dr. Justin Cook, a colleague from University of Central Arkansas, also invited Hausback to perform on his new album, “Connections.” They toured the southeast U.S. in September 2019, performing several recitals.

Dr. Jason Hausback practices for an upcoming performance with Dr. Justin Cook (left) and Dr. Michael Schneider (right).

“One thing that sets Jason apart is his background in jazz combined with his interest in classical music,” Cook said. “The result is jazz that’s maybe more lyrical than some other artists and classical that has a bit more of a groove.”

Hausback says his recitals are often like a buffet. Instead of playing the entirety of each song, he may play single movements from multiple songs. This gives the audience more variety and appeals to the casual classical listener, he adds.

Recitals give him an opportunity to teach as a guest artist on other campuses, Hausback noted. His students also benefit from being taught new methods by visiting artists who perform at Missouri State.

Teaching and inspiring

He loves the balance between teaching and performing – he pursued academia since he wanted to do both. He teaches individual trombone lessons to students who plan to one day become teachers themselves.

Often I play with people I went to college with. We have that experience of performing together before we got our college professorship gigs.

“It’s more than being a technically proficient trombone player. It’s about becoming a better musician and expanding that to being a better teacher,” Hausback said.

He uses recitals to introduce students to new or influential music, and hopefully inspire the audience. But sometimes, it can have the opposite effect, Hausback notes.

“In a world of curated, beautiful, aesthetically perfect content on social media, people are becoming more perfectionistic,” he said. “When my students hear a musician who plays a ‘perfect’ performance, some think ‘I can’t do that, so I might as well give up.’”

But Hausback encourages them, “facing your insecurities and encountering failure is how you learn.”

-

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

On broadway

This happened eight times a week at New York City’s Music Box Theatre as Brescia prepared to take the stage in the Broadway smash “Dear Evan Hansen.”

It was the seventh Broadway production for Brescia, assistant professor in the department of theatre and dance. Before joining Missouri State in 2016, she wowed audiences as Donna in “Mamma Mia!” and Elphaba in “Wicked.”

“My job is to tell this story, which is very emotionally loaded, in a way that reaches the audience.”

Brescia took an artistic leave from Missouri State, which allowed her to accept the contract with “Dear Evan Hansen.” She played Heidi, the title character’s mom.

Brescia described Heidi as “very flawed. She’s not killing it as a mom at all, but there are reasons for that. There’s a whole history that led her to the very moment the play begins.”

How she found her character

Exploring and inhabiting such history is a cornerstone of Brescia’s acting technique, which she teaches to her advanced acting students.

She requires them to get very specific about the given circumstances of their characters’ lives. Brescia’s students create extensive autobiographies for their characters, thoroughly defining the world in which the characters live. Such specificity, Brescia said, leads to the truthful behavior that’s central to good acting.

“So for instance, if I have a line about a childhood pet, say a dog named ‘Fox,’ I create a whole history for that,” she said. “Then when I’m on stage and I mention Fox, I’m actually experiencing a fully-realized memory, which enlivens the work.”

“Lisa sets professional expectations for her students, and she does it in a caring way. It’s leadership by example, and they rise to her example.” — Dr. Kurt Gerard Heinlein

As Brescia prepared for “Dear Evan Hansen,” she dug deep into the world of Heidi, a single mom trying to provide for her 17-year-old son. In addition to working full time at a nursing home, Heidi is attending night school to become a paralegal. She hopes this effort will improve her career trajectory and by extension, her sense of self-worth.

“She’s trying to juggle it all, and she’s flailing,” Brescia said.

And even though Heidi is a devoted mother, Brescia saw her “sometimes needing her son more than he needs her — or at least asking more from him. In some ways, she’s dependent on him.”

Crowds begin to form outside New York City’s Music Box Theatre, which houses “Dear Evan Hansen.”

Each of these circumstances, Brescia said, contributed to her understanding of Heidi as “a very shame-based person.” The character seems hounded by the sense that she’s falling short; as Brescia put it, “she’s kind of embarrassed to be her. But she’s working so hard.”

And despite — or perhaps because of — this insight, Brescia developed deep affection for her character.

“I see her as someone who’s constantly willing to show up for everything and do her best,” Brescia said. “As imperfectly as she does, she still shows up.”

Emotional accessibility

“Dear Evan Hansen” tackles complicated issues, such as mental illness and suicide. It approaches these hot buttons with openness and honesty, and audiences typically respond with enthusiasm.

Brescia knew this show called for emotional accessibility, but even amid highly charged moments, she kept her focus on telling the story.

“As I’ve gotten more experienced, I’ve been able to become more vulnerable. I’m also not afraid to get it wrong.”

“When actors are swimming in feelings, it can make us think the scene must be great,” she said. “But our job is to be full of those feelings and then put our attention on our scene partner. We have to make it about fighting for something.” She often reminds her students to ask, “What am I doing?” rather than “What am I feeling?”

And for Brescia, the chance to tell high-stakes stories like “Dear Evan Hansen” is a benefit of her work.

“I believe we all walk around with complexity and pain and grief inside,” she said. “I get to let it all out and leave it on the stage.”

Physical stamina

Performing in a Tony Award-winning show like “Dear Evan Hansen” required Brescia to deliver a consistently excellent experience — eight times each week.

This took physical stamina, particularly because she was performing on a raked stage, which means the stage platform itself was built on an angle with a downward slope toward the audience.

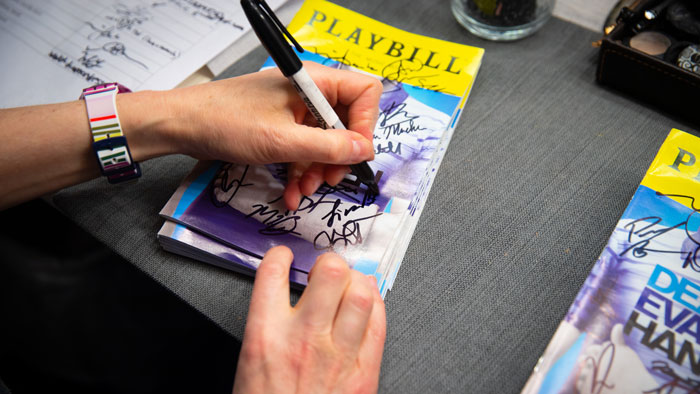

Lisa Brescia sits backstage autographing playbills for her Broadway show.

“It’s prettier from the audience’s point of the view,” Brescia said. “Because of the angle, they can see all the beautiful stage pictures.”

As an actor working onstage, however, she had to be cognizant of the effects.

She explained, “Cumulatively, for the skeletal structure it’s as though you’re working in really high heels all the time. The leg muscles and the IT bands tighten, and the knees can get pulled to the side. For me, this causes knee, leg and back pain.”

To combat these issues, Brescia took advantage of physical therapy sessions provided for the “Dear Evan Hansen” cast by its producers. She took additional steps to maintain her strength and alignment by scheduling regular massage and chiropractic treatments and by properly warming up for each performance.

“Our students can go see Lisa on Broadway and say, ‘I have the potential to do that if I put the work in.'” — Dr. Kurt Gerard Heinlein

And it helped that her character was costumed in “regular people clothes,” including medical scrubs.

She laughed remembering how this contrasted with a previous experience. “When I played Elphaba in ‘Wicked,’ I spent Act 2 performing in a 50-pound dress!”

Backstage life

When asked what people might find surprising about her experience in “Dear Evan Hansen,” Brescia described the contrast between the “pretty, glossy pictures” onstage and the constant motion occurring backstage.

“There were so many people involved in making what happened on stage look good and run smoothly: the stage managers, the company managers, the stage crew, the wardrobe crew, the hair crew, automation technicians, the spotlight operators, the house staff and box office personnel who serve patrons.”

And with such a large group collaborating to make the show happen, the backstage choreography was just as intricate as what was happening out front.

She recalled, “I knew exactly where I needed to be so I would not be in someone else’s way. At the same time, it’s really fun back there. We’re all pros, which means we’re focused, but certainly not glum.”

Daniel Mortensen, former hair supervisor for “Dear Evan Hansen,” secures Lisa Brescia’s wig backstage as she transforms into Heidi Hansen.

And the relationships, she said, grew very close. For example, “Most days, I spent more time with my dresser and hair person than I did with my husband. My dresser was with me as I changed clothes. It’s an intimate profession, and dressers must have sensitivity and intuition. When I walked off stage drenched in tears from an emotional scene, my dresser was there.”

Now, Brescia is happy to be back in the classroom with her students. She looks forward to what the future will bring — certainly more acting work and possibly some new paths as well, such as directing.

“I believe in sort of universal forces, like a warm hand on my back, pushing me through my fears and saying, ‘You are supposed to do this. Keep walking; just keep walking.’”

- Story by Lucie Amberg

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Singing between the lines

The message came from an 87-year-old woman in Missouri. Days earlier, Payne, a professor of music and professional opera singer, performed with the Springfield Symphony for a special Black History Month concert in February 2018.

There, Payne’s baritone delivered soaring solos and narrated the second half of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The woman wanted to attend the performance at Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts. Unfortunately, she had to wait to hear the show on the radio.

“You gave me my soul back with your songs and your wonderful voice and the things you said today,” she said. “You gave me my life back.”

And she went on.

“I have to tell you that I’m losing my eyesight to degeneration,” she said, “but I once was blind, but now I see. Thank you. Bless you.”

Dr. Todd Payne demonstrates technique to his vocal students.

Payne turns off the recording. He sits back in his chair as a state of contentment washes over his face.

“It made me realize that I am exactly where I am supposed to be, doing what I am supposed to be doing,” he said, tapping his index finger on his desk with each beat.

“If I never get to the Metropolitan Opera, it’s OK, because I know I was put on this Earth to touch the lives of others through the power of music.”

In April 2018, one dream came true when he sang at Alice Tully Hall, a concert hall at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in Manhattan.

A lifetime performer

Payne estimates that his career includes hundreds of performances. The list includes more than 30 recitals and major performances in the last five years. And that doesn’t include the hundreds of times he sang at church and other family events.

What I tell my students, and I instilled this in myself, is that practice prepares you for the persistent pursuit of your predestined purpose.

He also teaches voice at Missouri State, in courses that range from the 100 to 600 levels.

Payne shared that voicemail with his students to drive home a central point: He’s here to teach them so much more than singing.

“My research is going underneath the surface,” he said. “I look at music and ask, ‘What is it saying? How does it apply to me, and how can I give that back to the audience?’”

When he walks out on stage, the audience sees or hears him as Dr. Todd Payne. But Payne himself said he experiences an out-of-body sensation.

Student Emily McFadden practices with Dr. Todd Payne.

“Every time when I walk on that stage, I leave Todd Payne in the wing outside and I walk on as whoever I am beginning to personify,” he said. “All of a sudden, I feel like I’m just floating when it comes to singing.”

The key to that, he says, is practice. Oh, and legendary basketball player Michael Jordan, who Payne has admired for decades.

Payne read Jordan’s autobiography, which made him realize what drove Jordan to win a half-dozen NBA championships. The principle applies to Payne’s performance career and how he teaches his students.

“Jordan said that he played in practice as if he was already in the NBA Finals,” Payne said. “That was his mentality.

“I practice and perform as if I’m getting ready to make my debut at the Metropolitan Opera. I teach my students as if they, tomorrow, are getting ready to change the world.”

Student Alex Smith and Dr. Todd Payne perform a duet in class.

One of Payne’s former students, Chris Boemler, echoed that statement. Boemler spent parts of nine semesters under Payne’s wing, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in music education in 2012.

He now teaches choir, guitar and music theory at Festus High School in Festus, Missouri. Payne inspired him to never give up on his students, and to teach them that true music lies in the intent with which notes are performed.

“He really helped me on my sense of drive with my voice and finding my true voice,” Boemler said.

Payne also helped senior music major Emily McFadden find her voice in and outside of music. McFadden took private lessons from Payne and said the professor’s wisdom assisted her quest to succeed in college.

“He’s adamant about taking care of yourself,” she said. “He helped me understand how to draw boundaries and say ‘no’ when I need to. College requires a personal drive, and he taught me how to be my own motivator.”

Teaching inclusion through music

About two years ago, Springfield Symphony music director Kyle Wiley Pickett approached Payne with an idea.

The director wanted to do something special for Black History Month in February 2018. Payne said he’d love to put together a group of selections.

When you find the meaning of music, I believe you give an audience more than just a beautiful voice or entertainment. You’re being vulnerable to share part of who you are with them through your singing.

On several occasions, Payne had recited the second half of King’s famous speech and was familiar with gospel music and hymns. A concert was born.

“It was magical. That was the first time that, to my knowledge, the symphony had ever performed ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand’ and ‘We Shall Overcome’ with narration of Dr. King’s words,” Payne said.

“Truthfully, this show was born out of love.”

Students from one of Dr. Todd Payne’s classes. Submitted by Payne

Payne said he’s a storyteller, and that he tells his students that their job is to touch the lives of those who are in the audience.

“You’re advocating for the continuous fact that music is a universal language that washes away from the soul the everyday dust of life,” he said.

“That’s what you have to be an advocate for. Music sees no color. It sees people for who we are. We’re stronger together as one.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Carter Williams and Chris Gawat

Further reading

Sinking suspicions: Predicting future disasters

“When a house falls into a sinkhole, neighbors clamor for information. They ask if their house is next,” said Dr. Doug Gouzie, geology professor at Missouri State University. “It’s unimaginable and devastating, but I think they might not really want the answer to that question.”

Gouzie studies land formations, like sinkholes, and how water forms them.

“Your house being built on a plot of land doesn’t create a sinkhole. It’s not the weight of a structure,” he said. “The right conditions must already exist underneath the ground.”

He’s one of about 100 doctoral-level people in the country studying these structures. His goal: predict the next sinkhole site.

If you have a new sinkhole, people always want to know where did all the dirt underneath go?

Common themes

By investigating sinkholes, Gouzie finds similarities. Each finding moves him toward that major end goal – one he’s not sure will be reached in his lifetime.

His studies have revealed a variety of contributing factors. In a residential neighborhood where a sinkhole swallowed a house, he found a correlation between sinkholes and mature trees.

“Mature trees are very, very good at finding water,” Gouzie said.

Dr. Doug Gouzie and graduate student Jordan Vega explore Smallin Civil War Cave.

Roots often spread out to gather water. If roots fight their way through cracks in the underground rocks to find a reliable source, there might be a problem.

“If a tree happens to find a crack that leads them to a cave passage with a stream, that makes them happy. Then they grow better,” he said.

In this particular case, the owner had cut down a tree, but the stump remained. Gouzie said it’s unclear whether grinding out the stump, yanking it out or leaving it would lower the risk of a sinkhole.

Because the tree was now dormant, the roots shriveled up, leaving significant cracks in the rock. Anything like this, which funnels water underground, can make the ground vulnerable to caving in.

Once water finds a path, it will keep seeping through. You’re not going to create Fantastic Caverns in 50 years, but you can in a couple of million years.

How it works

About 20% of the United States is built upon limestone or other carbonate rocks, which are called karst lands. When rain falls, the acidity in the rain slowly dissolves that rock.

Gouzie likens it to a marshmallow in a glass of water. First the marshmallow gets goopier, then becomes marshmallow fluff and finally dissolves.

Dr. Doug Gouzie’s graduate students get hands-on experience collecting water and sediment from local caves to trace the paths of waterways.

When rain water hits the soil, the small soil particles can wash out through the dissolved holes quickly, he noted.

The appearance of the soil in your yard can tell a story, too. If you see areas with lighter soil while other areas stay a richer brown, something may be amiss. The lighter area may indicate the water has dissolved lime. Instead, the water is moving somewhere deeper.

“If I know where the landscape is draining into – where it’s going underground,” he said, “then I know where it’s washing the soil away. That’s where I’m going to find the next sinkhole.”

Dye tracing

Along with his graduate students, Gouzie spends many hours in caves across Missouri and on stream banks collecting water and sediment.

Jordan Vega, graduate student, works with Dr. Doug Gouzie to identify which waterways lead to which caverns.

“Nature gives us the results that will help us predict what sinkholes or drainage areas are connected with which cave or spring underground,” he said.

One way they determine this is by placing dye in the streams – detectable by black light but not the human eye. Using an instrument with a very sensitive electric eye, the team can trace the dye’s path, even when the spring meanders underground.

As a kid, I just found water fascinating.

Director of the Missouri Geological Survey Joe Gillman appreciates how Gouzie’s work also seeps into other areas, such as water quality and public health.

“He’s addressing real geoscience challenges affecting people’s daily lives,” Gillman said. “His research routinely focuses on finding solutions for … not only his community, but also the citizens of Missouri.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Traveling scientist: Finding a home in the lab and field

Instead, it’s the work of the Japanese beetle. But it’s never just one. The beetles arrive in multitudes out of the earth. From white grubs chewing on the roots of your plants, they grow into a swarm that blankets your plants. They eat the tissue, damaging the plants beyond survival.

For farmers, the beetles’ attack is an even greater concern. It’s devastating to a crop, yet it’s just one example of the pests that plague the agricultural industry.

I tend to work with very simple materials, but I’m asking very important questions.

Tipping point

Dr. Maciej Pszczolkowski walks through the vineyard at the Mountain Grove campus. He points out leaf after leaf heavy with Japanese beetles. Staff spray the vines every five days, yet nothing is deterring them today.

It’s a double-edged sword, according to Pszczolkowski, agriculture professor hailing from Poland. Pesticides are necessary, but they should be limited.

“The question is how to mitigate pesticides’ detrimental impact on the environment and humans,” he said.

In the orchard, Dr. Maciej Pszczolkowksi searches for signs of agricultural pests.

Much of his research now focuses on determining that tipping point. What is the least amount of pesticide to apply that allows for the minimal damage to crops but still allows for the necessary amount of pest control? He also looks at improving pesticide formulations, application procedures and the careful timing of application.

The plant and the pest

Pszczolkowski approaches these issues in a variety of ways. He studies the pests – both their biology and their habits. As a brain physiologist, he tries to answer questions about why pests behave the way they do.

He also studies the pest-resistance of different plant varieties.

In the lab, Pszczolkowski’s students look for alternatives to traditional synthetic pesticides. The team tests plant essential oils that could be used as natural insecticides. These bio-insecticides target specific insects.

Japanese Beetle found on a plant at the Mountain Grove campus of Missouri State.

Synthetic pesticides damage human health, water quality and wildlife. They also kill natural pollinators, according to Pszczolkowski’s graduate student, Michael Fenske.

“Synthetic pesticides, while effective, will eventually cause many serious problems that will not be reversible,” Fenske said. On the other hand, bio-insecticides are natural and don’t harm the environment.

Pszczolkowski, who has published more than 60 peer-reviewed articles in his career, loves the balance in his work. He enjoys working in the lab with his students to identify natural solutions to these agricultural problems.

Dr. Maciej’s work in this field of research is essential to everyone’s overall well-being. – Michael Fenske

But nothing compares to the outdoors, he says.

Evolution

Pszczolkowski points to evidence of codling moths plaguing the apple orchard as he ambles among the trees.

“Repetitive use of chemicals leads to insect populations resistant to those chemicals,” he said. “We simply kill sensitive individuals and let the naturally-resistant individuals reproduce.”

To overcome this in the apple orchard, the first three rows remain pesticide-free. This method builds a refuge for the fruit feeders.

Maciej’s work can help people use pesticides more effectively – thus working smarter to reduce waste and protect the environment while still meeting pest management needs. – Dr. Deirdre A. Prischmann-Voldseth, North Dakota State University

Years ago, he discussed this strategy of pest control with Dr. John Dunley, a colleague at Washington State University. Pszczolkowski remembers Dunley saying “insecticide resistance is simply the visible spectrum of evolution. To combat it, one must interact with evolutionary forces, such as natural selection.”

Sustainable future

Pszczolkowski has earned a reputation for understanding insects and manipulating their behavior. He serves as a reviewer for 18 journals in the field. He’s also received more than a quarter of a million dollars in grant funding for projects since coming to Missouri State.

When he looks to the future, he hopes to influence the United States Department of Agriculture’s recommendations on pest control.

Dr. Maciej Pszczolkowksi closely examines the vineyard and orchard at Missouri State’s Mountain Grove campus.

He’s an innovator. So a few years ago, he tempted the codling moths to feed on the foliage instead of boring into the fruit. It took many trials, building off research he had conducted while working in Taiwan, at Washington State University and Kansas State University. Ultimately, he patented a chemical that drives away codling moth larvae from the fruit causing them to feed on foliage and die of natural reasons.

He also designs species specific traps and tests their effectiveness. For a farmer, Pszczolkowski points out, these traps or pesticides have to make economic sense.

“I want to give something to the grower: an insecticide, a method, something,” he said. “Because there are times when one of these would benefit more than the others.”

His work matters: For the overall economy to succeed and for the health of the population, he said, we depend upon farmers’ success.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Securing natural resources for the Ozarks

The Ozarks region is known for its rich natural resources. Forests. Lakes. Rivers. Streams. And they’re all interconnected.

Proper management of these natural resources ensures that they’ll be available for people to enjoy for many years.

Dr. Robert Pavlowsky has worked on nearly 100 projects related to water quality in the Ozarks region of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. He is the director of the Ozarks Environmental and Water Resources Institute, also known as OEWRI, and a distinguished professor of geography.

“I’m a geographer. We view the world at different levels.”

The institute supports efforts to protect and restore water quality and supply in the Ozarks. Since it was created in 2004, the institute has administered 86 grants worth almost $5 million.

Dr. Robert Pavlowsky’s team uses this surveying and assessment equipment in their study of the Mark Twain National Forest.

“Our research is focused on helping managers understand the effects of their management programs on the landscape, stream behavior and floods,” said Pavlowsky. “We also give the managers third-party support so that their decisions have scientific backing.”

Impact of prescribed burning on water quality

One current project Pavlowsky leads is assessing the impact of prescribed burning in the Mark Twain National Forest.

The U.S. Forest Service contracted with the institute to see whether prescribed fires are increasing soil erosion and harming water quality in the area.

“When we focus on understanding a watershed, we also work with the uplands, hill slopes, floodplains, streams, and local communities.”

Pavlowsky and about a dozen students have been monitoring rainfall, soil conditions, runoff channels and water flow within the Big Barren River watershed in Mark Twain National Forest.

“So the question is,” said Pavlowsky, “does prescribed burning increase runoff from forest soils and cause more flooding and pollution downstream?”

Preliminary results indicate a small improvement in soil conditions one to two years after a burn, compared to unburned sites. This positive effect, in turn, leads to less runoff and soil erosion, and ultimately decreases water pollution in the watershed.

Research opportunities for graduate students

Interest has moved to other parts of the watershed.

“We’re also looking at stream channels because they connect the forest areas, and what washes off them, to larger creeks downstream with year-round water and aquatic life,” said Pavlowsky.

Joshua Hess and Annie McClanahan are working with Dr. Robert Pavlowsky, researching the effects of controlled burning on soil conditions and water quality in the Big Barren River watershed.

Graduate student Grace Roman is evaluating the headwater channels for her graduate thesis. The research is in a sub-specialty called fluvial geomorphology.

Fluvial geomorphology is the study of the form and function of streams and the interaction between streams and the landscape around them.

“One of his previous students studied how prescribed fires affect soils,” said Roman. “So we’ve gone from upland soils to the water in the stream. And then I’m sure he’ll have someone looking further downstream to see any effects from prescribed burning.”

Paying it forward

Pavlowsky involves students in most of his research. Since coming to Missouri State in 1997, he’s mentored well over 150 undergraduate and graduate students.

He sees student involvement as core to the university’s, and his own, mission.

(Left to right): Joshua Hess, Annie McClanahan, Dr. Robert Pavlowsky, Madeline Behlke and Grace Roman in the Mark Twain National Forest.

“MSU’s mission is more to educate students in research rather than to produce faculty that dominate in their fields — although some do,” he said.

“I love working on research problems with students. When I was in graduate school, one of the aspects that really affected my future career was noticing that faculty – who were busy, good teachers, and talented researchers – took time to work with me and to mentor me along.”

Larger implications

While most of Pavlowsky’s research is on a specific waterway or area, much of what’s learned has broader implications.

“Our research findings get shared among other scientists and environmental managers, so it adds to our understanding of how watersheds and streams work so that we can better protect them,” said Pavlowsky. “A lot of what we’re finding out can be applied to other streams in the Ozarks.”

- By Andrea Mostyn

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Living with a Lisp

“No one says, ‘I love having a lisp,'” Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz said.

A lisp is common in preschoolers and often recurs when a child loses teeth. In some cases, speech therapy can treat a lisp, but not always.

Lockenvitz, assistant professor of speech-language pathology, studies the life experiences of those with a persistent lisp.

“Something as minor as a childhood scar, acne or body odor can affect your self-confidence. A lisp can, too,” she said.

She started her career studying how to transcribe and articulate certain sounds. It was a very black and white, quantitative research project.

But reading a personal account of one author with a lisp led her to explore the softer side of research.

“I’m interested in storytelling,” she said, “and the reflections of a life with a lisp.”

Lockenvitz began recruiting subjects to interview. Quickly, she found that identifying subjects to participate was a major hurdle.

Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz creates a mold that will be used to form a SmartPalate.

As she advertised online, many initially responded that “they knew someone who would be perfect for the study,” she said. After more careful consideration, many bowed out. They reported that they couldn’t broach the subject with their friend or family member. It was too sensitive of a subject.

Coping mechanisms

Eventually she gathered a large enough sample size to proceed. Once she began collecting surveys and interviewing subjects, several themes appeared.

Some were predictable: feeling different and lacking confidence in social encounters. But other themes that surfaced surprised Lockenvitz.

Stuttering and lisping affect speech patterns differently, but they both have immense repercussions on communication.

Avoidance appeared as a common coping mechanism for those in her study.

A person with a lisp might avoid words with prominent “s” or “z” sounds. This avoidance interrupts the flow of conversation to reword a response. It not only slows conversation, but it adds to the feelings of isolation and being different.

“I had a participant who talked about only memorizing vocabulary words in his SAT preparation book that did not have s’s in them,” Lockenvitz said. “It blew me away.”

Avoidance had become so ingrained in his life. He automatically skipped over the difficult words – even in a scenario that wouldn’t require him to say them.

Social sensitivity

Lockenvitz also analyzed the responses and identified a lack of social sensitivity toward lisping. Previous studies on stuttering showed that people recognized it was socially unacceptable to tease someone for this speech disorder. Those with a lisp still felt victimized.

Student Allie Savich uses a SmartPalate in the Speech-Language and Hearing Clinic.

“Making fun of speech problems is apparently acceptable in our current state of society,” Lockenvitz said. “It’s sad.”

One speech language pathologist who participated in the study had a lisp herself. In addition to difficulty with the sounds, she had a visual lisp. Her tongue thrusted forward, protruding between her teeth.

She shared how her colleagues talked about her lisp behind her back. They put her on the spot, at times making her feel shame. But the worst critic was her daughter, the up-and-coming comedian.

“It was part of her bit,” Lockenvitz said, “the speech pathologist with a lisp. It really hurt her mother.”

One of the participants said, through her tears, ‘I want to tell this story. I want to contribute to your research because it’s so important. It really has affected me emotionally.’

Testing technology

Lockenvitz is collaborating with Dr. Alana Kozlowski, associate professor of communication sciences and disorders, on a project to retrain lisping tongues using biofeedback.

A SmartPalate used as a feedback device in Dr. Sarah Lockenvitz’s research on lisping.

Graduate students in the Speech-Language and Hearing Clinic take molds of the mouths of adults who have a persistent lisp to design a palate. The palate, with sensors inlaid throughout, can be placed in the roof of the mouth. Once connected with the software, it can show the contact points between the tongue and palate.

“The clients have a visual to show them where the tongue should be to make the sound correctly,” Lockenvitz said.

While the technology has been used in the field for many years, Lockenvitz and Kozlowski are using it in an innovative way. They are applying the principles of motor learning along with this technology.

When motor learning is used in an intervention strategy, clinicians offer feedback to work toward independence and consistent accuracy.

The treatment or interventions for persistent lisping requires more research, she added, but the possibilities excite her.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Carter Williams

Further reading

Making space for everyone

It is easy to forget that everyone has a different life experience.

So, what happens when cultures collide on college campuses? How are different life experiences blended or rejected? How can universities accommodate and appreciate everyone?

These questions drive Dr. Jake Simmons’ work. He researches the experiences of students of color on college campuses. His goal is to improve diversity and inclusion programs.

“It’s important to create safe spaces to share experiences,” Simmons said. “It’s important to students and to the fabric of a university.”

As the graduate studies director in the communication department, he uses his research to step into the shoes of others.

“Diversity and inclusion programs can be most effective when they are constructed through a relational partnership.”

It began in 2013

Simmons studied Black students’ experiences in predominantly white institutions, also known as PWIs. He researched through a relational dialectics lens.

Ashleigh Bobo talks during Dr. Jake Simmons’ auto-ethnography class. Photo by Jesse Scheve

Relational dialectics, to put it simply, is studying the competing tensions involved when we speak about an issue.

“We are always speaking twice,” Simmons said. It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it.

He and his collaborators conducted individual interviews and focus groups. In total, 67 African American students answered questions about their lives at PWIs.

The students felt conflicted. They wanted to participate in their own culture. To gain acceptance, though, the students felt they had to take part in dominant traditions.

“I always believe there is an amazing social justice fight.”

The study received national attention in prominent news outlets, like Inside Higher Education and The Huffington Post.

“It was surprising that it became national news,” Simmons said. To him, it seemed obvious.

What are institutions doing wrong?

According to Simmons, institutions make one primary mistake when they develop diversity and inclusion programs. In too many cases, student experiences are not considered.

Dr. Jake Simmons advises more than 60 graduate students in addition to his teaching load at Missouri State. Photo by Jesse Scheve

“Students of color need to be offered the opportunity to tell their institutions what they need. Administration needs to give them the space to do so,” he said. “This might not sound novel, but it’s very rare that it ever actually happens.”

If these programs are woven into the fabric of universities, Simmons believes institutions will retain more students. This is especially true with international students.

“You constantly have to ask the people you are serving what they need and figure out better ways to give that to them,” Simmons said.

Bringing inclusion home

At Missouri State, Simmons advises more than 60 graduate students and brings new information into the classroom.

“I think Missouri State is a model institution in regard to student inclusion, but there is always work to be done.”

He collaborates with Dr. Shawn Wahl, dean of the College of Arts and Letters. Together, they wrote a new textbook for the intercultural communication curriculum. They aim to improve students’ cultural competence at MSU and beyond.

“Our work together, on both journal articles as well as a book focused on intercultural communication, has made me a better person,” Wahl said. “It is an ideal situation to work with highly competent people who also exemplify kindness, humility and professionalism. Jake does all of it.”

It’s personal

Simmons’ passion for his work has developed outside of the classroom as well.

His four children are multicultural and multi-ethnic. This turns his work into a passion project out of love and protection for his kids.

Along with minority student experiences, Dr. Jake Simmons also studies posthumanities – or what it means to be human in a world obsessed with technology. Photo by Jesse Scheve

“I want to create a better future for them,” he said.

For everyone else, Simmons sees a future where we are more understanding and more accepting of each other.

That world starts with you.

“Trust yourself, your voice and your cultural voice,” Simmons said. “It matters to change institutions and the classroom. It matters in the world.”

- Story by Lauren Stockam

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Blending history, pubs and politics

That’s the reality today.

But in the 19th and early 20th centuries, public houses (nicknamed pubs) didn’t offer food.

You may think it changed in order to turn greater profits. Instead, Dr. David Gutzke argues that pubs evolved in Great Britain as a ripple from the Progressive movement. He believes his greatest scholarly contribution is that he established the Progressive movement as a transcontinental movement. Previously, it was considered as American as apple pie.

Gutzke, a distinguished professor of history at Missouri State University, set the stage in his book, “Pubs and Progressives.” He focused on the period between World War I and World War II. Historically, it is known as the interwar period.

I don’t want to write the same type of book that somebody else might do.

As a professor of British history, an international scholar on the topic of alcohol use and a historian looking at social change, he has published more than 20 books and articles on these subjects. “Pubs and Progressives” nicely knits these interests together.

If you build it, they will come

“The brewers were trying to change the type of people you expected to see in pubs. They wanted middle-class people as customers. Brewers wanted respectability,” he says, “both for themselves and public houses.”

This aligned with the Progressive movement’s values. Progressives wanted to right social ills. They desired efficiency, discipline and order. And they sought government intervention to improve society.

You have to understand the past on its own terms.

One brewer Gutzke studied, Sydney Neville, wrote in his memoir he felt personally responsible to the general public to discourage drunkenness.

“The slogan of the whole movement was, ‘We do not want people to drink more beer. We want more people to drink beer.’ I thought it was very clever,” Gutzke said.

One way to attract a different clientele: Brewers spent tens of thousands of pounds beautifying spaces, adding courtyards, gardens, linen tablecloths and fresh flowers.

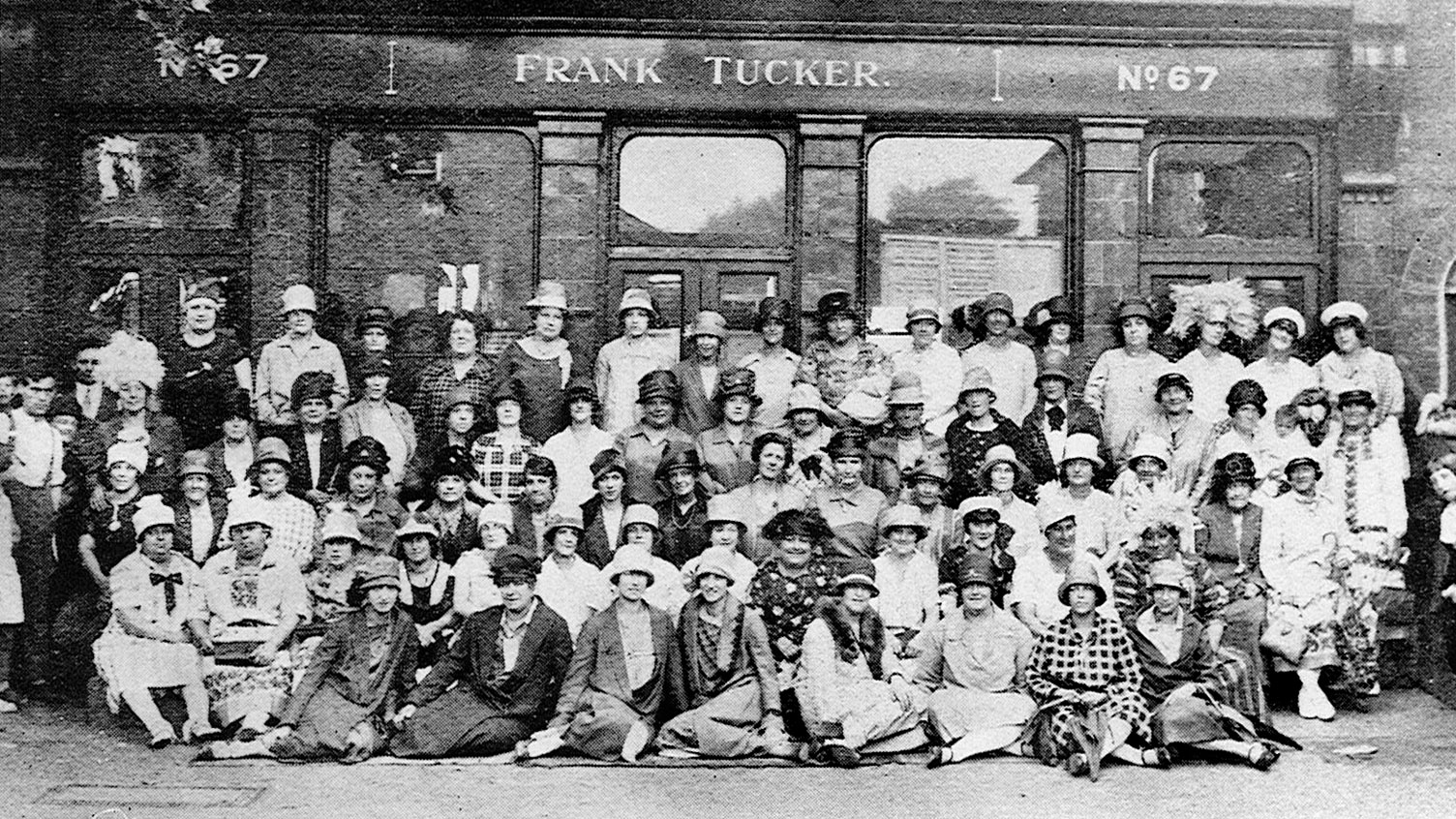

In an attempt to draw in more women or upscale clientele, brewers redecorated and expanded their offerings. Photo submitted by Dr. David Gutzke

“Before the first World War, the pub was a masculine republic. Progressive brewers were very keen to bring women in,” Gutzke said. “They believed women could act as a restraint on drunkenness.”

Money hungry?

Then brewers expanded into offering a full menu. Food made the pub seem like a respectable place to spend time and eat dinner as a family.

You must not allow present-minded concerns to be projected into the past.

Large Progressive brewers, like Neville, recognized building new, expensive pubs would likely eliminate smaller, “less scrupulous competitors,” who tolerated drunkeness to maximize profit. This statement alone says Progressive brewers desired profitability, but not at the expense of moderate drinking. More importantly, notes Gutzke, it reveals a desire for social change.

“Neville writes in the preface of his book, ‘I just hope that people come to understand what we were doing after I’m dead,’” Gutzke said.

Finding the evidence

Digging into publications from political scientists, anthropologists and sociologists, Gutzke drew a more robust world picture. This comparative history helped him identify the Progressive movement in Britain.

I like the way they frame questions differently. I like to think in those terms.

Gutzke also gathered photos, ledgers and legal documents to see the buildings before and after renovations, as well as changes in sales over time. For “Pubs and Progressives,” he gathered data from about 6,000 pubs.

“He is a master researcher who ferreted out all sorts of records that are difficult to locate,” said Dr. William Rorabaugh, a colleague from University of Washington. “He interviewed a significant number of leaders in the alcohol industry – an industry which is perhaps understandably ordinarily very tight-lipped.”

The proprietors of The Man of the World drew this large group of women to the pub in October 1928. Photo submitted by Dr. David Gutzke

British mystery novels from the interwar period also proved insightful.

“In a roundabout way, novels that aren’t trying to be historical documents can accurately depict the general public’s perception of life,” Gutzke said.

The general public, he says, thinks historians write history books to get everything factually correct for future generations.

“The truth is an abstract concept,” Gutzke added. “Historians engage in how to understand the past.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Kevin White

- Historical images provided by Dr. David Gutzke

Further reading

Looking for connections

Our lives are full of connections.

You see someone you know in the grocery store two aisles over. What’s the quickest way to get to them?

Your parents live 2,000 miles away. There are no direct flights. Which flight has fewer layovers?

Connections are rarely as easy as point A to point B. There are stops along the way, twists, turns and sometimes you may even get lost.

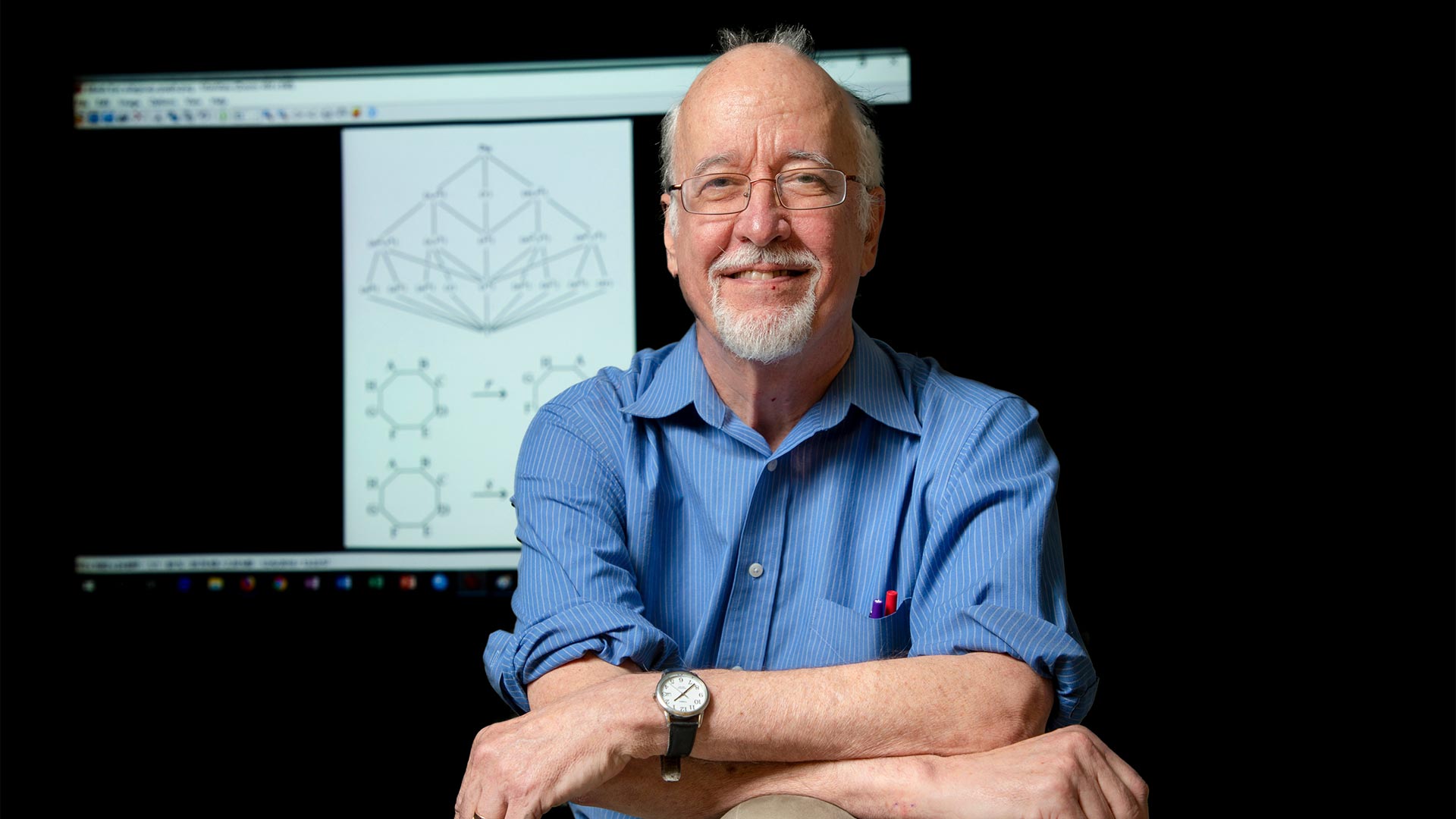

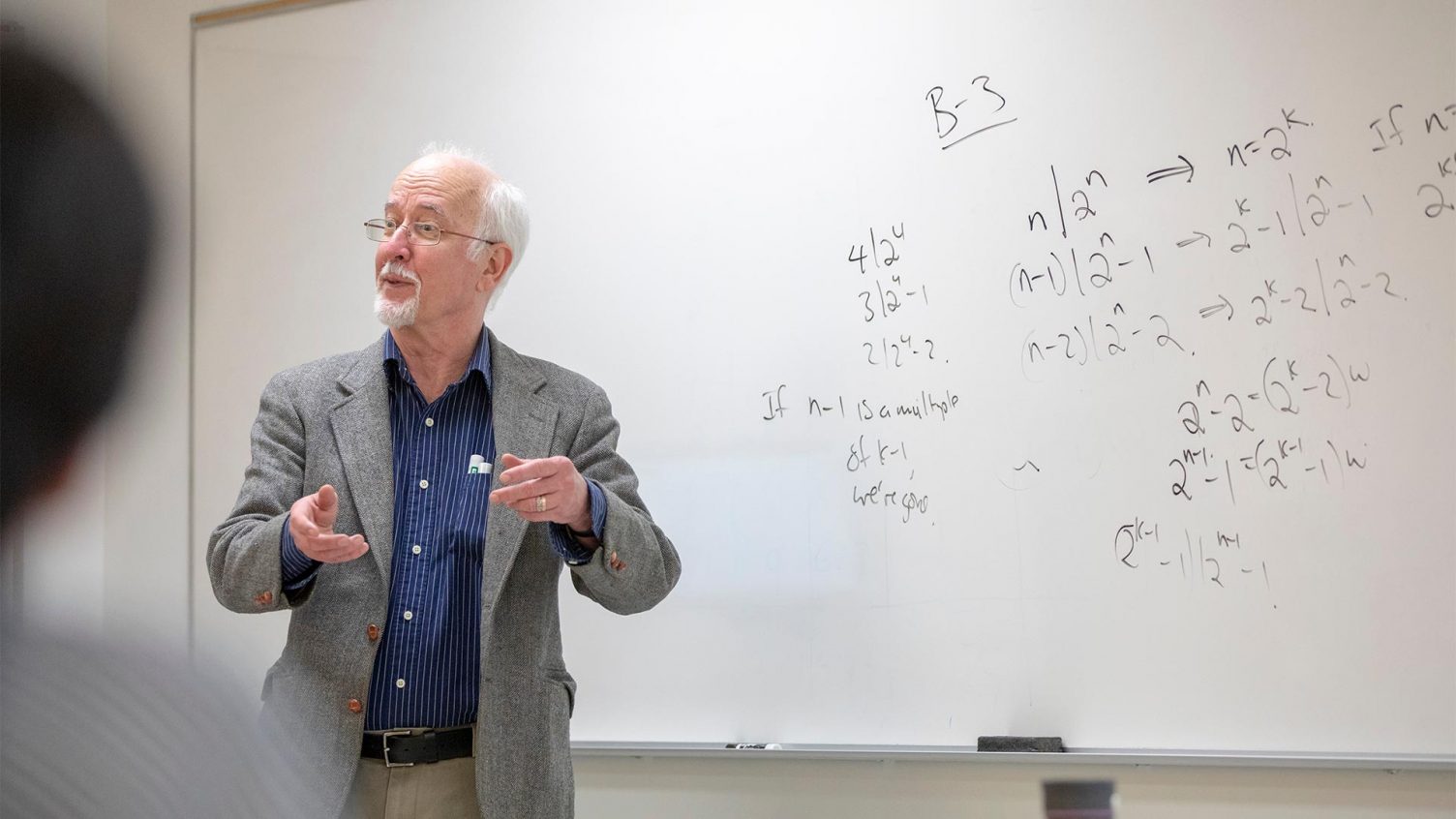

Dr. Les Reid, professor of mathematics, studies similar connections.

Finding that connection

“People don’t realize that there are questions in math that we can’t answer yet,” Reid said. “Geometry is 2,000 years old. Calculus is 400 years old. You might think there’s nothing new under the sun. But there’s a lot of stuff that we still don’t understand.”

For more than 10 years, Reid has looked at how to start one place and end up another.

You’ve got groups, an algebraic object. Then you have graphs which are these interconnections between. Groups show up throughout chemistry, physics, crystallography and more. — Dr. Les Reid

Take a triangle. It has three points: A, B, C.

Turn it in whatever direction. It still has those points; they are just in different places now.

Then, instead of turning it, flip it like a pancake. The points are still there, they have just changed again.

How do you get back to the original location? How have these points changed?

Reid looks at all of these data and maps them on a graph. He uses algebra and geometry to find his results.

“Dr. Reid is one of the most brilliant mathematicians in our department,” said Dr. Richard Belshoff, professor of mathematics at Missouri State. “He has an incredible breadth and depth of knowledge of virtually all areas of mathematics.”

Dr. Les Reid teaches students about mathematical problem solving. Photo by Bob Linder

A math textbook

It all started with a question by one of Reid’s students, Joseph Bohannon.

He saw a figure in a textbook that intrigued him. He and Reid set off to find an answer.

Reid said he was surprised by what they found. He figured that he and Bohannon would get partial results.

My main concern is to study. There are a few universities that have math in the humanities college because we’re more interested in this abstract system of mathematics. — Dr. Les Reid

It’s hard to get actual, full results in math. Instead, they ended up classifying a whole group of shapes.

“What was surprising was that a complete classification was achieved,” said Bohannon. “I expected that there might be stragglers all over the place.”

Looking forward

A lot of the time, mathematicians are leaving a legacy rather than practical solutions. Reid doesn’t know how his research will be utilized in the next 100 years.

Reid uses nineteenth century Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan as an example. Ramanujan loved that his mathematics were pure, with no immediate application.

“One hundred years later, some of the stuff that Ramanujan was doing is the basis for business on the Internet,” Reid said. “He thought his work was so pristine and beautifully abstract. Anything to do with the real world is messy and ugly.”

Though Reid doesn’t know what will come of his work, he does know why he does it.

“Most mathematicians study mathematics for the inherent beauty of it,” Reid said.

Reid’s studies have led to more than 25 published publications in prestigious journals with 10 in progress. He has also collaborated with many prominent mathematicians throughout the world.

“My main interest is to study basic questions in math,” Reid said. “We may not know what the future applications might be, but gaining a deeper understanding of the fundamental principles of mathematics is essential.”

In addition to problem solving, Dr. Les Reid teaches courses in geometry, algebra and calculus. Photo by Bob Linder

Creating the next generation of mathematics

Reid also works with Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). This National Science Foundation funded project allows top notch math students to come to Missouri State for the summer to work on mathematical problems.

Dr. Reid was endlessly patient with me and seemed to know something about every branch of math, which was exactly what I needed. — Joseph Bohannon

Bohannon’s problem led to three summers’ worth of REU projects. Some students looked at graphs. Some looked at groups of shapes. They intertwine algebra and geometry looking for connections.

Though Reid calls his work the most basic of research, it has endless possibilities.

- Story by Tori York

- Main photo by Bob Linder

Further reading

Getting your message across when systems fail

Although traditional communication systems may falter, data can still transfer from phone to phone until it reaches an area with service. This is called a wireless ad-hoc network – one of Dr. Hui “Anita” Liu’s research interests.

When there is no central server, how can we implement a network functionality?

According to Liu, devices must cooperate to form this network. Each phone shoulders a slice of the burden. Together, they have the strength and functionality to relay and process data.

In a computer lab, Dr. Hui Liu listens as a student poses a question. Photo by Bob Linder

Better together

I like change. I think computer science always give you an exhilarating feeling.

While humans might elect to cooperate in this manner – to work for the greater good – does a wireless system?

“Every device needs to contribute by spending its energy,” said Liu, computer science professor.

She’s published and presented more than 20 times internationally on the topic of networks without central infrastructure.

To study this, she and her collaborators model networks and use computation to mimic the real peer to peer network. Then they monitor how the devices work and learn.

“As you improve cooperation level, you improve the performance of the whole system,” she said.

Peer to peer networking is a burgeoning field, changing all the time. In previous research of these systems, researchers assumed devices would act as rational humans.

“There’s this assumption that the devices would be selfish – maximizing individual benefits,” she said.

However, Liu’s latest research projects assume that some will act as altruistic punishers rather than rational humans.

“Humans have a predisposition to punish those who violate group-beneficial norms,” Liu said. “This is true even when it comes at a cost to the punisher.”

This is altruistic punishment.

I think my work is important to you because I can provide you better user experience in the future using your smartphone.

Her research team designed an experiment based on this assumption. They wanted to see the effect on cooperation.

To do this, she simulated a group of devices. Ten percent would act cooperatively. The other 90 percent were programmed as noncooperative. She found some of the cooperative devices converted to altruistic punishers. Many of the noncooperative devices were eliminated. This allowed the new network to perform.

Dr. Hui Liu looks on as students work on developing smartphone applications. Photo by Bob Linder

Pioneer in the field

All of her research projects come down to this: How can smartphone user experiences improve?

Deng Li, a colleague from Central South University in China, has collaborated with Liu on many projects. Li noted that Liu is intelligent and diligent. With these qualities combined, Li believes Liu’s work will continue to influence this field.

“In her research, she creatively applies theories and statistics to solve computer science problems,” said Li.

As technology capabilities change, Liu feels confident developers will focus on networking in a decentralized environment. And she is excited to be part of this evolving field.

Because if you’re on the battlefield or trapped inside a flooding house, the service could save your life.

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Main photo by Bob Linder