Archive for 2020

Humans as sensors: Making technology more intuitive

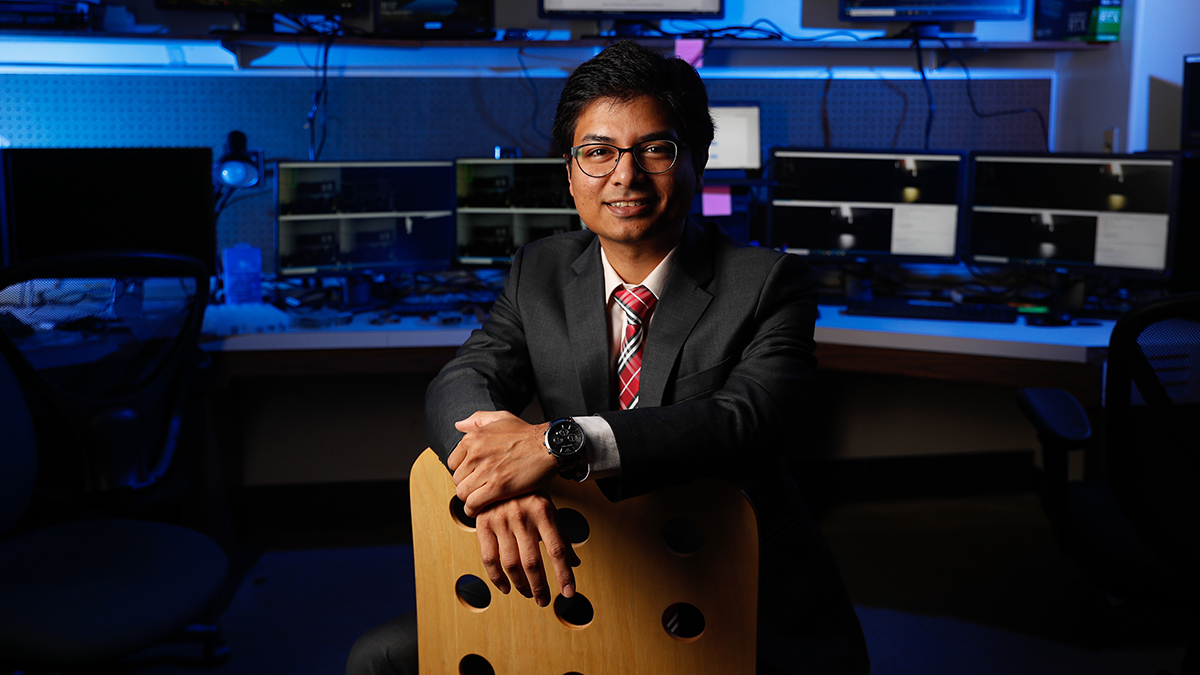

This question fuels the research of Dr. Razib Iqbal, associate professor of computer science at Missouri State University. Much of Iqbal’s research revolves around multimedia and the Internet of Things, or IoT.

What is IoT? It could be anything connected to the internet — from a smart meter and appliances to smart smoke detectors and wearables.

These things are capable of collecting information about the physical world around us for processing.

The multimedia-based branch of IoT, called Internet of Multimedia Things, includes content like images, audio and video. This newer branch of technology opened the door to Iqbal’s latest interest: sensing the smart home more accurately via multimedia.

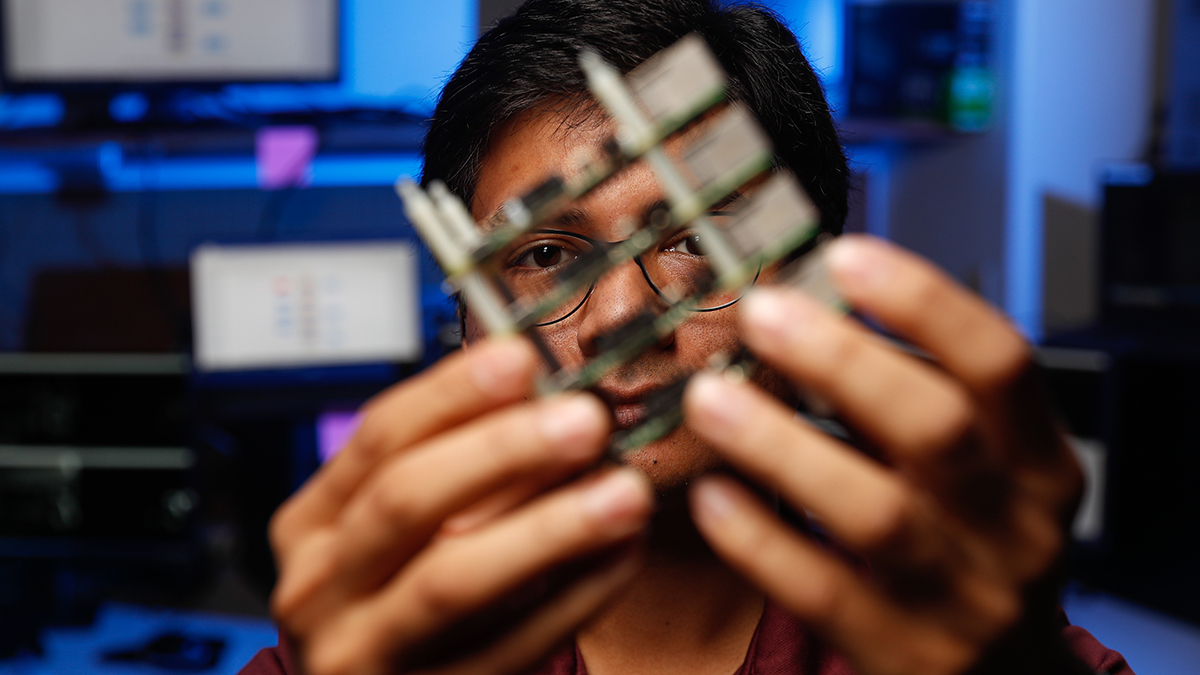

Cupped in his hands, Dr. Razib Iqbal holds several Raspberry Pi sensor modules. These tiny components are responsible for streaming data.

Humans as sensors

What does the future of the smart home look like from Iqbal’s perspective? Here’s a clue: Humans serve as sensors in the ecosystem of connected things.

“Using ordinary microphones and cameras, we can gather information about users’ states,” Iqbal said. “This content is key to improving the smart home experience.”

Imagine turning up the heat in a room by saying it was cold or using sign language to turn lights on or off. Picture a system that prompts you to play a specific song or adjust a room’s atmosphere to match your mood.

“This includes recognizing voice commands and gestures, detecting emotions and differentiating between humans and pets or other objects, among other forms of sensing.”

These uses could support users’ convenience and mental well-being. Others could contribute to their physical safety and security.

“If an intruder entered the smart home, the more intuitive system could detect fear in a homeowner’s voice,” Iqbal said. “Then it could automatically dial a number and stream the conversation occurring in the home.”

The system could especially benefit a more vulnerable population of loved ones: the elderly. They may experience memory impairment, which makes remembering device commands for Amazon Alexa and Google Home difficult.

Elderly individuals also often experience falls, which the smart home system could detect.

“Existing fall detection systems rely on physical sensors. Some people take them off before showering or going to bed, rendering them useless,” Iqbal said. “Being able to analyze video data of smart devices to detect falls could be life-saving.”

The work of Dr. Razib Iqbal will make smart homes and other IoT devices more intuitive.

Meeting in the middleware

Smart homes contain sensors and devices that allow homeowners to automate tasks remotely using a computer or phone.

These devices and sensors use set commands to control a limited range of functions – like turning things on or off. Their traditional IoT system can only process simple information with little data.

“Multimedia data is continuous and bulky. It demands more computer memory, bandwidth and processing power for real-time decision making,” Iqbal said. “Adding in a multimedia component to the IoT burdens the system further.”

Iqbal published research in the Elsevier Internet of Things journal. The article presents a novel framework for overcoming this challenge. Iqbal proposes that the high-processing software, called middleware, step in to help.

“He is one of the bright stars within our college and the greater university.” – Dr. Ridwan Sakidja

Middleware lies between the IoT operating system and the applications running on it. From there, it can intercept data from devices as they send it to the operating system.

Middleware converts multimedia content’s bulky data into a simpler form. Then, it sends the data back to the operating system to finish processing there.

Besides saving processing resources like battery power, middleware also saves users money.

“One smart device always leads to more. It would get very expensive if each had to process multimedia content itself,” Iqbal said. “Streaming the content to middleware is a much cheaper option — one that eliminates the need for expensive connecting devices.”

A cluster of Raspberry Pis, like this, can store and stream data, improving the smart home experience.

Building the foundation

Most of Iqbal’s research has centered on use of Internet of Multimedia Things in smart homes since joining Missouri State’s faculty in 2015. In his academic career, he has published more than 35 peer-reviewed articles in leading journals and conferences.

Iqbal is the founding director of the Multimedia Systems and Communications Laboratory at Missouri State. He collaborates with both undergraduate and graduate students on research there.

“I see it as an opportunity to instill in each student an understanding of and capacity for problem-solving, independent judgement and intellectual honesty.”

Iqbal’s research on multimedia content began as a graduate student, so he recognizes the importance of training his own students early on.

“Some might view it as an entryway into a research career,” Iqbal said. “I see it as an opportunity to instill in each student an understanding of and capacity for problem-solving, independent judgement and intellectual honesty.”

The work they produce will likely serve to make future technology more useful and user-friendly.

“Iqbal is always very open to exploring new ideas through collaboration,” Dr. Ridwan Sakidja, professor of physics and research collaborator of Iqbal, said. “He cares a great deal about his students’ success.”

- Story by Ashley Lenahan

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Making a name in wines and spirits

One man whose dedication and expertise have advanced the facility’s operations is Dr. Karl Wilker. He serves as manager, winemaker and distiller. He’s also a research professor in the Darr College of Agriculture. The college houses the winery and distillery, which is part of the Missouri State Fruit Experiment Station.

Creating commercial wines

During his horticulture PhD program in the 1980s, Wilker immersed himself in winemaking. It grew into a passion.

For more than a decade now, this passion has driven him to develop the best wines possible at MSU. He uses grapes grown at the Fruit Experiment Station.

“Before I took over the winemaking, we were making port only. So, I started taking all the varieties of grapes we grew and making different types of wine,” Wilker said.

Among the wines currently produced and sold include Chambourcin (a French-American hybrid), Cynthiana (dry red), Norton (Missouri’s state grape), Pink Catawba (sweet blush) and White Blend (crisp white).

“I like the challenge of doing things to a high-quality level, and continuously learning and advancing.”

Tasting and comparing batches: Dr. Karl Wilker and Jeremy Emery work to perfect these spirits in the distillery.

To make high-quality wines, Wilker applies the science of chemistry, fermentation, food processing and microbiology. But ultimately, it comes down to smell and taste. Wilker relies on his experience of tasting many types of wines, and his sensory skills, honed through the years.

“You have to try a lot of different products and emulate the best ones,” Wilker said. “The process is very sensory-guided. You have to get a feel for what quality is.”

Experimenting with rum

Besides winemaking, Wilker also focuses on distilling. In recent years, he has made rum in the distillery. He mixes molasses with water and leaves the mixture to ferment and distill. The resulting rum rests in oak barrels and ages for about two years.

How does Wilker know when the rum is ready?

“I taste and keep tasting. I have an idea of the average time it should take, but each barrel has a different fermentation and composition,” he explained. “The quality of the final product is the result of many decisions and actions during its production.”

Dr. Wenping Qiu is Wilker’s colleague in the college who researches grape genetics. He believes Wilker has taken the university’s winery and distillery to the next level.

“Dr. Wilker doesn’t hesitate to try new methods in producing new styles of wine or spirits,” Qiu said. “He adjusts every detail in winemaking to make high-quality wines and has revived the distillation operation for commercial production.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Racking up awards

In 2007, Wilker led efforts to enter Missouri State’s wines and spirits into competitions.

“I saw it as a way for us to show what was going on here and evaluate what we’re doing,” Wilker said.

Since then, he and his team have won 60-plus awards from competitions across the country. These include the Jefferson Invitational Wine Competition, Mid-American Wine Competition and New York World Wine & Spirits Competition.

“If you don’t have a feel for what quality is, it’s really hard to get anywhere because that guides everything we do here.”

Two of the top awards won are the Jefferson Cup Trophy (2019 and 2016) and Sweepstakes winner (2016 and 2014). Rum took home the first award for 2020 – a silver at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition.

Dr. Karl Wilker walks through the vineyard at the Mountain Grove campus.

Sharing his expertise

In his role, Wilker imparts his knowledge and skills to community members. Over the years, he has led or co-presented more than 30 workshops. They range from home winemaking to wine tasting and distillation.

Wilker also supports grapes genetics research – like Qiu’s. He takes the new varieties of grapes and turns them into commercial bottled wines.

“It’s a good test for the grapes to see if they survive the winemaking process,” Wilker said. “Dr. Qiu’s team can then evaluate the quality of the wine and show it to people in the industry.”

He added that so far, he has worked with two new varieties, a white grape since 2016 and a red one from 2019. The former looks promising.

“If we don’t have someone like Dr. Wilker who makes wines out of new grapes, we can’t release new grape varieties,” Qiu said.

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Aim for competent communication in collaboration

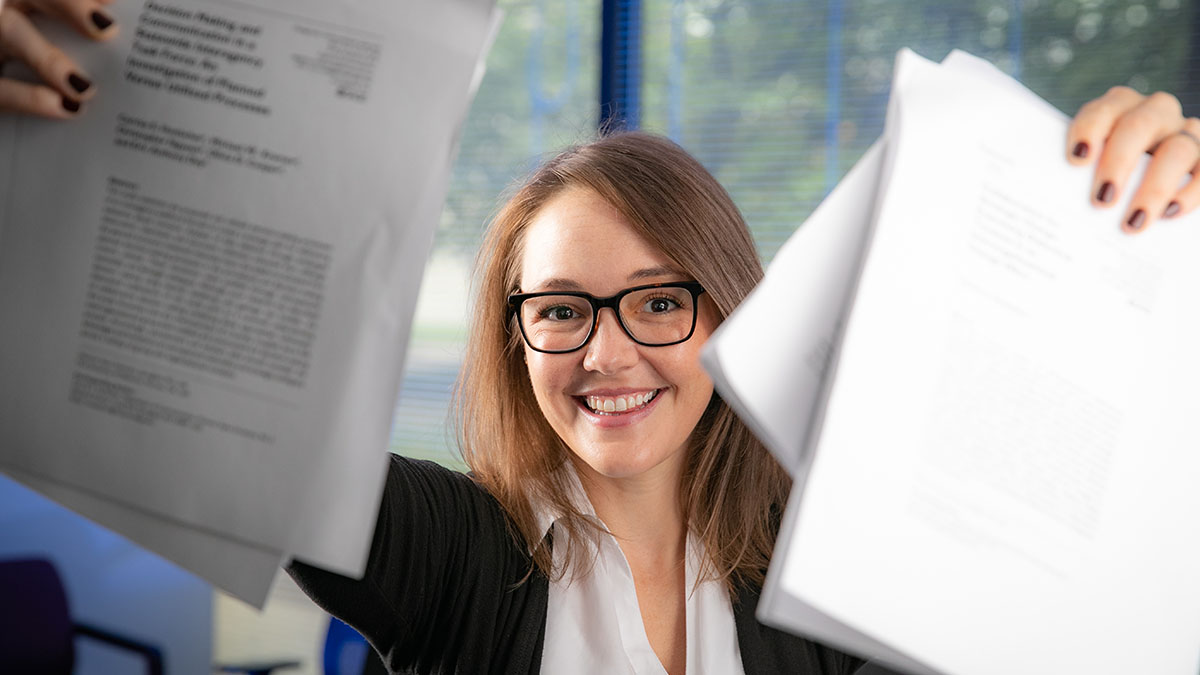

Dr. Carrisa Hoelscher, director of graduate communication studies at Missouri State University, sets her target on competent communication to help others improve their skills. This includes finding ways to improve both effectiveness and appropriateness.

Being effective and appropriate can feel like they are at odds sometimes. This creates tension — Hoelscher’s research area. She examines tensions in collaborative communication, like in committees within the nonprofit or governmental sector.

“Do we err on the side of appropriateness, or do we err on the side of effectiveness when communicating? That’s kind of the undercurrent of everything,” Hoelscher said. “When I’m studying small-group interaction, what I’m most interested in is the underlying tension people tend to feel but don’t have words for and what they can do to address those tensions.”

Hoelscher carved out a niche at the intersection of collaboration and tension to provide suggestions to improve communication in groups. So far, she’s co–authored a textbook, published many articles and contributed to several books. She’s always looking to produce practical lessons for application in real-life scenarios.

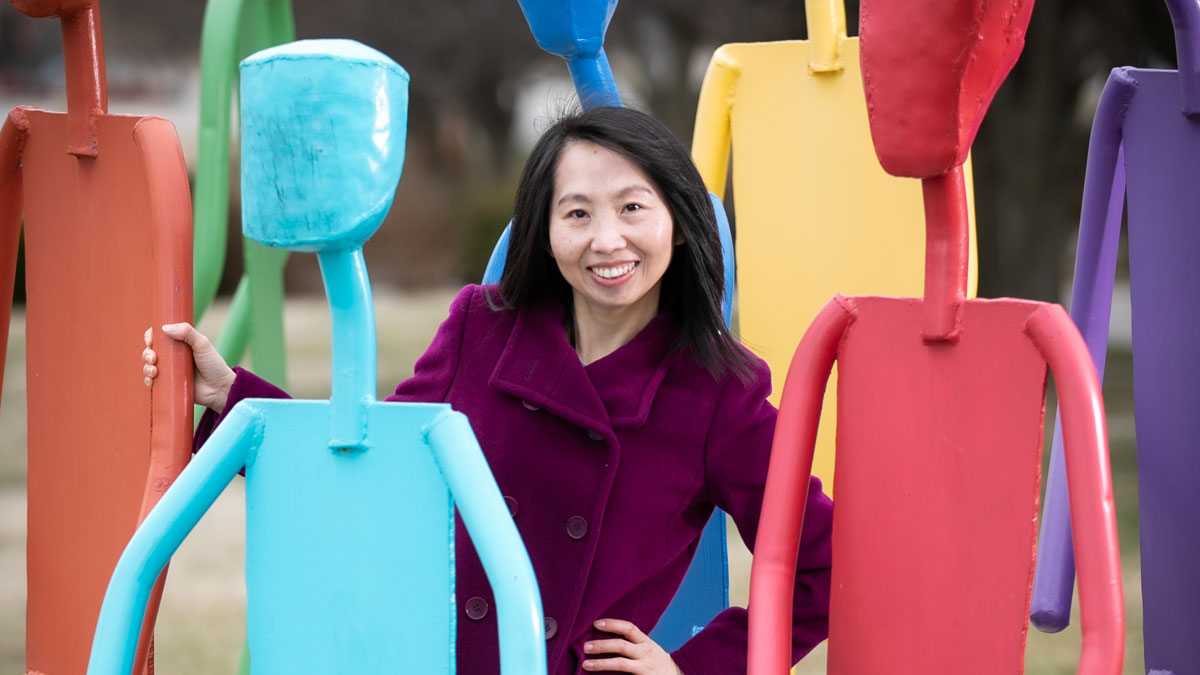

Collaboration comes with unique tensions. Dr. Carrisa Hoelscher studies these in hopes of improving the experience.

Working together

When grave community issues creep up, task forces with agency representatives often come together. Each offers a different perspective, set of resources and ability to address the needs.

“These agencies are trying to make the world a better place,” Hoelscher said. “We’re seeing agencies having to collaborate more — to do more with less.”

For one study, she followed an interagency group as it developed and implemented a strategic plan to address substance-abuse issues. She observed the meetings for more than three years, detecting and tracking tensions in the talk among collaborators. She also interviewed participants and collected documents to help categorize types of tensions and document the shifting meaning of these tensions for group members over time.

“We have the luxury of going for effectiveness in our own organizations. Meanwhile, almost always, in a collaboration, you have to err on the side of appropriateness, because the relationship is flat and fragile.”

As a result, she published a new article in 2019 on tensions in collaboration and is currently working on a follow-up project. This line of research outlines seven dialectical tensions collaborators may experience. It also provides a framework of best practices for managing those tensions.

“These are tensions, like autonomy and connectedness,” Hoelscher explained. “You want both. You can have both. But they feel like opposites.”

Other examples include skepticism and optimism, collaborative and competitive, creativity and parameters, necessary and palatable change, and impactful and viable change.

Hoelscher’s work helps practitioners identify the tensions in their own experiences. The work also provides practical suggestions like acknowledging the tension, delaying tension management and hedging for more appropriateness.

“The traditional tension everybody uses as an example is a romantic relationship. Almost everybody feels the tension between wanting to feel connected, but wanting to maintain autonomy and independence. We want both of those things at the same time, but they feel like opposites.”

These tactics can help people to successfully manage the uncomfortable moments and use the tension to lead to better outcomes.

Getting a seat at the table is very important. Equally important? Keeping communication open between all parties. If not, says Dr. Carrisa Hoelscher, the collaboration will fizzle.

“In collaboration, we have to care more about the end product than our own organization because we are giving up something to get there and these tensions aren’t going away,” she said.

Many times, she added, the thing being given up is time to complete other tasks.

“’Are we getting enough bang for our buck?’ so to speak. That’s a common tension in these situations,” she said. “You have to be able to answer that question for everyone at the table and give them the tools to address those commitment-based tensions.”

Tensions lead to teachable moments

Hoelscher began researching this interagency collaboration for her dissertation under Dr. Michael Kramer. He is chair of the communication department at the University of Oklahoma.

“Carrisa’s work is changing the field,” he said. “She examines the way people actually talk and work together instead of focusing on the financial and other benefits that most researchers examine.”

Hoelscher notes that collaborative tensions must be managed differently or else the partnership will fizzle.

“When it comes to the types of tensions I talk about, discomfort may be telling you to pay more attention to a part that you’ve put in the back of your mind,” she said. “I hope my research contributes to making us more comfortable with discomfort.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Seeing the forest and the trees

This reduces the amount of sunlight hitting the ground.

If left in such a condition for too long without disturbance, important tree species cannot regenerate. Invasive or shade tolerant species creep in and animals leave the area, in search of better food.

Or maybe the trees simply age, produce less fruit and continue to weaken. These scenarios drive the forestry field and forest management decisions.

“Forest management is intentional, planned disturbance,” said Dr. Michael Goerndt, assistant professor in the Darr College of Agriculture at Missouri State University. “When forestland is managed for multiple objectives, we can effectively grow better trees and companion crops and maintain diverse habitats.”

He explains that it comes down to planning for ecological succession. This entails designing the future of the forest and predicting what it will be under specific conditions.

With a father and brother both in forestry, Goerndt learned about forestry since he was a young boy. He’s a self-proclaimed “math goon.” This led him to specialize in forest biometrics focusing on measurements and data analysis for forests.

“Everyone should have a better understanding of statistics. We use it constantly. Most people are using it daily and don’t even think about it. They talk about how many miles per gallon their car gets. That’s stats.” – Dr. William McClain

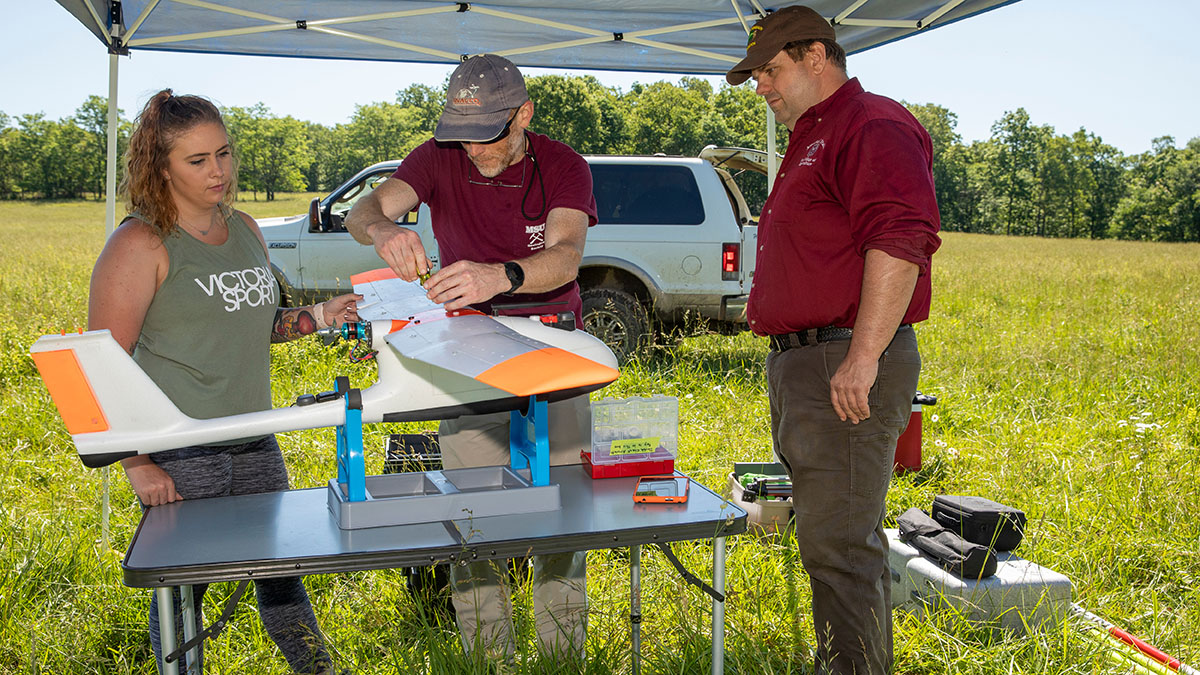

This now incorporates the latest technology, such as remote sensing, satellites, drones and spectral imagery. Using these tools, he collects data from forest landscapes with help from geospatial science experts, like Dr. Toby Dogwiler.

A drone hovering over the tree canopy may reveal beautiful aerial imagery of the forest. But it also puts into focus the challenges that lay beneath.

“Technology gives us the opportunity to get data for very large areas more efficiently than we ever could with boots on the ground,” Goerndt said. “That’s where the science of forestry is headed. As our ecological challenges mount, we must look to the trees as a critical component for addressing landscape degradation, pollution, climate change and alternative fuels.”

Left to right: Austin Livingston, Stewart McCollum, Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, Dr. Michael Goerndt, Dr. Toby Dogwiler and Bailey Wolf at Missouri State’s Journagan Ranch.

Productivity of land

Goerndt has grown the curriculum for forestry at Missouri State, and published more than 15 articles in the last 10 years. Many of these publications have come from his research assessing potential biomass availability in forestlands.

Now he’s working on a collaborative study, funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture with Dogwiler, Dr. William McClain, Dr. Melissa Bledsoe and two graduate students. The study will showcase exactly how much more productive an area of land can be if managed for multiple crops and products.

“I’m proud of the fact that we made it work that two students are going to get their degrees out of the project.” – Dr.William McClain

In the initial phase, Goerndt and his collaborators identified three study sites at Missouri State’s Journagan Ranch.

“We’re creating the capacity here to do years and years of long-term research,” he said.

Dr. Michael Goerndt talks with graduate student Stewart McCollum.

There’s a control site of about five acres comprised of tall fescue. A second five-acre site of natural mixed hardwood forest has been thinned down to simulate a savannah. The third plot, about five acres, will be a site of a walnut plantation for research and future collaboration with Hammons Black Walnuts.

Using these sites, the team will compare cool-season and warm-season forage growth. They will investigate the synergistic relationships between trees and forage. They will also assess the economic and ecological benefits of intentionally converting either fields or forests into silvopasture land, which means managing land to integrate trees with livestock grazing.

“The silvopasture project is right for in the Ozarks because we’ve got a vast amount of two things: trees and cows.” – Dr. Michael Goerndt

On all of his projects, though, Goerndt wants to bring it down to earth and show the practical application.

“In a nutshell, I always want the takeaway to answer one question: ‘How can the real stakeholders apply this in their lives?’” Goerndt said.

Dr. Toby Dogwiler (center) and graduate student Bailey Wolf (left) prepare a mapping drone with Dr. Michael Goerndt.

Growing biodiversity

Through a sustainability lens, Goerndt’s work is very valuable. In addition to identifying sites with the greatest potential for renewable energy sources, he advocates for greater biodiversity.

Rather than continuously simplifying the landscape and allowing one species to dominate a forest, his research brings to light how different species can coexist in a mutually beneficial relationship.

“Foresters know in most cases we are never going to see the full fruits of our labors within our lifetime. The rotation is too long.” – Dr. Michael Goerndt

Biodiversity also builds in safeguards for the agriculture industry.

“If you build a plantation with one cultivar of a crop, you open yourself up to potential devastation,” Goerndt said. “What happens if a fungal disease comes along and wipes out that particular variety? You’re done.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Root of the problem

But as the availability of cultivable land diminishes and as climates change, our ability to grow enough food is becoming limited, too.

This is the root of Dr. Laszlo Kovacs’ research. He’s a geneticist interested in the agricultural industry.

“For most of history, we didn’t have to worry about food,” said Kovacs, biology professor at Missouri State University. “Now, with a huge and rapidly increasing population size, we are faced with many challenges. We have to start using land that is not ideal. And, as a result of the climate emergency, we have to deal with more extreme weather conditions.”

All of this leads to an impending food shortage.

“Not just any food will do,” he said. “We desire quality food, right?”

His focus is on studying grapevine rootstocks to identify genes that will make plants hardier for the necessary conditions. He looks at the genetic makeup to identify traits for disease and pest resistance, drought tolerance and flood tolerance among many other characteristics.

Students take samples of grape hybrids at the Darr Agricultural Center.

Two wild grapes

Kovacs’ current research projects build upon his previous findings, like the identification of genes that make grapes more resistant to a fungal disease. He’s contributed more than 20 peer-reviewed journal articles in the past 10 years and serves as a reviewer for 10 industry journals.

“Laszlo Kovacs is a leader in the field of plant genetics and grapevine natural history, and an outstanding collaborator and mentor,” said Dr. Allison Miller from St. Louis University. “The breadth and depth of his knowledge provides novel insights into grapevine biology and beyond.”

More than anything, this Hungarian-American loves being in the beauty of the Ozarks collecting wild relatives of the cultivated grape.

He and his students have been collecting plants of two interesting North American grapes: the riverbank grape and the rock grape. These grapes have been the cornerstone of his studies during the last 10 years.

“Once I see that glitter in my students’ eyes, they hit the ground running on helping with research.”

The riverbank grape roots where the soil is always moist. Instead of rooting down, the riverbank grape spreads its roots horizontally. But why? It’s in the genes.

Graduate student Sujan Thapa (left) and Dr. Courtney Coleman (right) accompany Dr. Laszlo Kovacs on a trip to Swan Creek.

On the contrary, the rock grape grows in drought-stricken areas. Its roots grow straight down to find water. Again, this trait is encoded in its genes.

These two species have adapted to their respective habitats as a result of evolution.

“Evolution is ‘product development’ over millions of years,” Kovacs said.

In the wild, a plant dies if its genes don’t match the environmental conditions under which it grows. A plant that has the “right genes” will be healthier and develop into a stronger, larger individual, he noted.

This results in more seeds. Then, a greater percentage of the next generation of plants will have the “right genes” for that area and climate.

Kovacs is attempting to identify genes that allow vines to adapt to the dry or moist conditions.

“We are interested in those genes and can transfer them to cultivate grapes or possibly other plants,” he said.

Dr. Laszlo Kovacs walks along Swan Creek with graduate student Sujan Thapa and Dr. Courtney Coleman.

Survival

The rock grape is found in the riverbeds of intermittent rivers and creeks. For instance, Swan Creek, one of his study locales, fills and flows for a couple of days, then dries up for weeks.

To find the water and nourishment to survive in this nutrient-poor area, the roots dive deep. His team realized that this would be a valuable trait for drought-prone areas.

“Every organism is trying to find its niche,” Kovacs said. “The rock grape found its niche by eking out a living under very poor conditions where other plants cannot.”

This is very advantageous in agriculture, he said.

“If we can identify the genes that enable these grapes to grow there, we have extremely valuable resources,” he said. “If you go to a desert area, maybe grapes with these rootstocks can grow. That provides huge economic opportunities.”

“Laszlo’s students, some of whom have joined graduate programs at St. Louis University, are among the most talented and promising students with whom I have had the joy to work.” – Dr. Allison Miller, St. Louis University

He’s not going to become a grape breeder, though. And he isn’t interested in transplanting these specific grapes in the desert. He’s experimenting with grafting other grape shoots onto these roots.

Grafting technology has been around for more than two millennia. A rose bush or the apple tree that you purchase is often the result of grafting two separate plants together.

For the past 150 years, grafting has also been used in grape culture.

“What we’re doing has an impact both locally and globally.”

Up to this point, the driving force behind grafting has often been to enhance the ability of growth of fruit trees and ornamental plants.

For Kovacs, it’s for our survival.

In his lab at Missouri State, Dr. Laszlo Kovacs demonstrates research techniques to his students Basant Hens (far left), Anh My Ly (left) and Emily Heaton (right) in his phenotyping course.

Team effort

To better understand the role the rootstock can play in crops, Kovacs is collaborating on a study with Miller and other scientists throughout the U.S. The multimillion dollar study, which is funded by the National Science Foundation, will be completed in 2021. However, the study has already produced results.

“For years, Laszlo has contributed to the collection of data and tissues, always generously sharing his knowledge, jokes and making light conversations during the long and very hot days in the vineyard.” – Dr. Allison Miller, St. Louis University

Using the riverbed grape and rock grape rootstocks, Kovacs and his team made a cross. Then, they grafted each of these new plants with the same scion, that is, a different plant which is forced to live with the rootstock and form the entire shoot system of the resulting composite plant. The genes of that scion are exactly the same in 300 plants — only the genes of each root are different.

“By doing this, we can very precisely study how the rootstock influences the characteristics in the shoot,” Kovacs said.

His team is also grafting other scions on the rock grape rootstock to map and identify genes. With this knowledge, the team can learn how to subtly modify features to make grapes more appropriate for different climates and conditions.

“Even though we’re interested in the root system, once we make an experimental hybrid, it’s easy for us to find genes that are responsible for disease resistance,” he said. “It’s a long process, but it’s important work. We are experimenting with plant biodiversity to make a more sustainable crop.”

For example, Kovacs noted that there’s a wild Norton grape variety in Missouri that is too high in potassium. If there’s a rootstock that is known to pull very little potassium from the soil, the

two could be grafted together to improve the grape production.

Student Basant Hens reports on data on the grapevines at Darr Agricultural Center for Dr. Laszlo Kovacs’ phenotyping class.

Back to the wild

Our ancestors, Kovacs said, selected plants with the largest seed and tastiest fruit to propagate the next generation of crops. However, they didn’t select based on ability to grow in poor soil.

“They didn’t have to, and they didn’t know how,” he said.

This selection method caused many ancient plant varieties and wild relatives of crops to become extinct or depleted over the years.

“Many people think this type of research is kind of romantic – this idea of going to the wild. Oh, but it’s very practical.”

Much of Kovacs’ work involves wild grape species because, biologically, saving native plants provides great benefits. Those species may have critical genes for something in the future, which is worth preserving. In fact, that’s how his team discovered the downy mildew resistance gene.

“We found it just because we looked at a new plant,” he said. “If we look at maybe 10 more plants, we might find five more new genes.”

This study helps grape growers, but ultimately, the knowledge can be widely applicable to all agricultural products.

“The future of humanity, to a great extent, is based on how we can provide enough food,” Kovacs said. “We have to dip into the vast genetic diversity of wild plants to see what they can provide.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Celebrating multilingualism

Should you stop speaking Spanish at home, for example, to help them learn English more easily?

Dr. Luciane Maimone, assistant professor of modern and classical languages, says no.

“Being an immigrant myself, I can relate to the powerful connection between language, culture and one’s sense of self,” Maimone said. “Maintaining children’s home languages is key to their identities and for their social and academic development.”

That’s because learning two languages at the same time is possible. While the learning process for bilinguals is different, children who succeed in preserving their home language can also fully acquire English.

Research shows bilingualism is linked to cognitive advantages and higher achievements in literacy and content areas.

An expert in the fields of cross-linguistic influence and language assessment, Maimone has published seven articles and presented at more than 16 refereed conferences.

Helping heritage speakers succeed academically

One of Maimone’s research projects explored the role of formal instruction in furthering heritage language knowledge. Maimone and her colleagues compared the effects of grammar and culture-based approaches on language complexity, fluency and accuracy among heritage Spanish learners.

Results suggested that relearning a home language was facilitated by reclaiming cultural connections more than by mastering grammatical rules.

“Developing writing and reading skills requires training more often provided outside the home.”

In the language classroom, Spanish heritage speakers face unique challenges. Unlike typical foreign language learners, they may start with higher levels of communicative competence. However, they may lack knowledge of writing conventions, formal language, and specialized vocabulary and terminology. This can result in low self-confidence, feelings of inadequacy or cause them to get lower grades.

For example, Maimone said, think about your own childhood.

“How often did your mother ask you as a child to write something for her?” she said. “You don’t have as many opportunities to write at home as you have to speak. Developing writing and reading skills requires training more often provided outside the home.”

The biggest challenge, however, might be to help heritage speakers see value in their linguistic experience and motivate them to build proficiency in their heritage language.

A possible solution? Maimone suggests starting programs for heritage speakers at secondary and postsecondary levels. This could help more heritage speakers in the state of Missouri achieve academic and professional success and become more confident in pursuing a college education.

Scholar Dr. Luciane Maimone looks at the best way to acquire a second or third language.

Assessing language and crosslinguistic influence

Maimone made a good impression on Dr. Ronald Leow, director of the Spanish program at Georgetown. Leow served as Maimone’s mentor while she worked on her dissertation.

“I found she was willing to listen to me, but also provided her own insights,” Leow said. “That’s a hallmark of a very good scholar. That she’s not just going to take my word for it.”

Maimone’s project explored the role one language plays in affecting someone’s ability to learn another. More specifically, how Spanish and Portuguese interact crosslinguistically.

“The primary goal should be improving the learning process and maximizing outcomes.”

She hasn’t accepted the status quo in the assessment field, either.

“Language testing is an exciting area, given the social and scientific implications of test results,” she said.

However, estimating how proficient a person is in a foreign language can be a costly process in both time and resources. Maimone became interested measures of language proficiency that are more readily available to researchers and teachers of language.

Maimone worked with the Assessment and Evaluation Language Research Center in Washington, D.C., to develop the first Portuguese C-test and the first automated Spanish C-test, an alternative test based on the reduced redundancy principle.

If you’ve been able to solve the Jumble puzzle in a newspaper where letters in words are out of order, that’s the redundancy principle at work. In other words, it’s your ability to recover meaning in oral or written texts that are incomplete or distorted.

She also worked in the development of elicited imitation tests for Portuguese and Spanish. These are oral language assessments that can be easily administered by teachers, adapted for language practice, and used as self-assessment tools.

“The future of language assessment is in measures that capture linguistic variability and creativity,” she said. “It’s about developing assessments that foster learner autonomy and success. These are assessments designed for learning, not for grading.”

That stands in contrast to traditional testing, which compares test takers to one another.

“Assessing students’ progress and abilities allows educators to make a wide range of decisions, but assessments are easily reduced to ranking tools or credentials for passing a class.” Maimone said. “Ideally, the primary goal should be improving the learning process and maximizing outcomes. Assessments must first be designed for that purpose.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Bob Linder

Further reading

Passing notes: Sharing a universal message through performance

Inside her office sit two grand pianos, with a desk pushed up against the corner. The sounds of students practicing drift through the walls. She prepares for performances in between lessons with students.

A Juilliard-trained pianist, Choi Witte, assistant professor of piano at Missouri State University, blends her teaching with a passion for performance.

She calls music a universal language. It speaks to everyone.

“When I’m performing, I’m trying to communicate with the audience through my music. It’s then up to the audience to decide how they’re going to receive it and how they’re going to translate it,” she said.

Taking music beyond the bounds

Choi Witte revels in the idea that music can cross cultural barriers that written language often can’t.

“It’s the one language for which you don’t need a translator,” she said.

As Dr. Minju Choi Witte practices on this Steinway piano, her music floods C. Minor Recital Hall.

She notes that music achieves its universality because human emotions are similar in every area of the world. You know someone is happy when they smile.

“You can connect with people on an honest, sincere, very raw level with music,” she said.

Choi Witte honed this idea in her 2018 piano album, “Boundless.” The title comes from her hope to embrace every aspect of your culture, even if you have more than one.

“Performance is impermanent. Recording “Boundless” was one way to make music more permanent for me. It feels good to have a tangible work that I can say, ‘This is what I did, and this is mine.’”

“I have two heritages: Korean and American,” she said. “With ‘Boundless,’ I wanted to explain that you can’t pull yourself into two pieces. You are one body.”

The record, consisting of three pieces in 11 tracks, draws inspiration from all corners of the world. American composers with international heritage composed each piece.

“The three composers can’t help but be influenced by their heritages,” Choi Witte said. “But, there are no boundaries in music. You can walk back and forth between many different parts of yourself.”

“The word boundless is saying there are no boundaries if you allow yourself to be inspired by your surroundings.”

What sets Dr. Minju Choi Witte’s performances apart? Her mastery lies in connecting with the music on a deep level.

The makeup of “Boundless”

Choi Witte’s colleague and friend Dr. Ching-Chu Hu composed the first piece, “Pulse.” It has subtle hints of Asian influence. The cadence of the four-track piece resembles the human heart as it experiences a whirlwind of emotions.

“I’ve had cardiologists sit in the audience when I perform ‘Pulse.’ They tell me at times it sounds like actual heartbeats,” Choi Witte said.

The second piece, “Sonata Andina No. 1,” draws from Latin American influence. Dr. Gabriela Lena Frank, pianist, composer and Guggenheim Fellow, combined the western sonata form with Andean folk music traditions.

“Gabby’s work is very much about the juxtaposition of two cultures, and how one doesn’t have to overpower the other,” Choi Witte said.

“Sonata Andina No. 1” uses the piano as an imitator of other instruments, such as guitar, drums, flute and marimba.

Dr. Philip Lasser, Choi Witte’s former Juilliard professor, composed the final piece “Sonata for Piano Les Hiboux Blancs ‘The White Owls.’” It’s French-inspired music that has followed Choi Witte throughout her career.

“It was the first contemporary piece I fell in love with,” she said. “I’ve known it since college, and I’ve performed it numerous times in the 17 years it’s been with me.”

Bringing meaning to the stage

Choi Witte’s mastery lies in performing works. For every piece she plays, she searches for a deeper meaning, something that helps her and the audience connect to the music.

“Sometimes you are given pieces that you don’t have a choice about,” she said. “It’s up to you to find something in the music that is convincing and meaningful because people naturally understand sincerity.”

In Dr. Minju Choi Witte’s office, she provides guidance to her music students.

She shares this wisdom with her students at Missouri State.

“I tell them it doesn’t matter if you don’t like the piece, because part of being an artist is connecting to whatever you’re given and taking it to the sky,” she said.

“I think a lot of different types of personalities can enjoy contemporary music. It has no pillars or traditions that dictate how you are supposed to perceive it.”

Performing someone else’s music adds another layer of pressure, but Choi Witte’s collaborators on “Boundless” trusted her artistry with their compositions.

“With Minju on stage, I can relax and let her playing transport me to the emotions I wish to convey,” said Hu, composer of “Pulse.” “I know I’m in very safe hands with Minju. She commands the piano and creates such beautiful sounds that she brings the music to life.”

Choi Witte admits she still gets nervous before performances.

“It helps to think about my students,” she said. “I’m teaching them to be the best they can be. The more I challenge myself and invest in becoming the best musician I can be, I can pass that on to them.”

- Story by Lauren Stockam

- Photos by Bob Linder

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Finding faith in college

He believes that perspective ignores the attention to the sacred and spiritual on campuses. It also doesn’t account for the intersectionality of religious studies. It overlaps with many other disciplines – from social work to politics.

The role of religion in higher education is a dynamic topic right now, he noted. But as a sociologist, he’s always been intrigued by how religion fits into the context of human society.

Attention on religion

In 2001, he and Dr. Kathleen Mahoney ventured into an extensive research project.

“We wanted to test our hypothesis that there is more attention to religion now than at any time since the post-World War II era,” he said.

They began collecting data and historical documents from all available sources. Then they conducted in-depth research to fill in the gaps.

Finally, in 2018, they published “The Resilience of Religion in American Higher Education.”

“It’s a sustained look at how religion has survived and persisted on college campuses despite a multitude of changes,” Schmalzbauer said.

It is Schmalzbauer’s second book in a career that has produced more than 60 articles, book chapters and reviews – all in the same “intellectual neighborhood.”

“John is so creative. He does not take what he’s experiencing for granted,” Dr. Elaine Howard Ecklund said. She is the director of the Religion and Public Life Program at Rice University. “He’s able to step aside from the institution of higher education, even though he’s part of it, and shine a scholarly light on the way religion shows up in unconventional ways in higher education.”

Moving mountains

For the book, Schmalzbauer and Mahoney, formerly of Boston College, researched the history of religiously-affiliated institutions. They performed surveys, interviews and site visits. One primary question kept popping up: Are these institutions less committed and connected to their religious identities than in the past?

“There’s more religion than meets the eye on any campus.”

Schmalzbauer said the answer was a resounding no. In fact, many administrators reported feeling more invested in this identity. Others described trying to find new ways to stress this mission, even if there were fewer figureheads, such as priests and nuns.

“We realized this story is so much bigger than religious colleges. It involved schools that have no ties to a church,” he said. “We underestimated the Herculean task of pulling this together.”

One part of Dr. John Schmalzbauer’s research is looking at the changing landscape of religion over time – especially on college campuses.

They investigated nonreligious public and private institutions. By reviewing curricula and research in many areas of study, they found overlap throughout the humanities, social sciences, health care and law. The intersection of these subjects further proved that religion provides context in diverse discussions.

“Religion has always been in dialogue with other ways of seeing the world on American campuses,” he said.

The increased presence of religion at universities, he noted, is due to the combination of those who see it as an object of study and people of faith.

“Education doesn’t erode your commitment to organized religion or to a spiritual quest; it may heighten it.”

Documenting the student faith groups and ministries, he gathered the number of groups as well as the membership. He tracked the numbers over many years, trying to be inclusive of not only the most well-established groups, but also the newer ones with more regional or local affiliations.

As time passed during data collection for the book, the numbers continued to change. Organizations changed names. Some vanished. New ones appeared.

With the arrival of new religious groups or as students begin identifying as spiritual or skeptical, the landscape shifted.

“John works through the history of religion in higher education and talks about the ways in which it waxes and wanes,” Ecklund said. “It’s the best of history, religion and sociology. And he reveals that religion is experiencing a real resurgence.”

But Schmalzbauer says, it’s also a snapshot in time.

“It’s too easy for people to say, ‘higher education destroys religion,’” he said. “The real story is much more complex.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Building friendships and battling bullying

“Having friends, even one good one, can separate the well-adjusted child from the at-risk youth,” said Dr. Leslie Echols, assistant professor of psychology.

When a child reaches adolescence, the brain develops more and starts sorting qualities differently. Youth begin to worry more about status, Echols notes. This brings about a greater likelihood of bullying behavior, and closes the doors on some friendships.

“My two cents has always been: If you can see someone as a human, you’re much less likely to mistreat them.”

It’s not always ill-intentioned, she says: Adolescents may not realize they are hurting others as they scramble to the top.

Echols, along with her colleague Dr. Sandra Graham from University of California – Los Angeles, received a grant of approximately a half million dollars from the National Science Foundation to establish an antibullying program. They will create a positive peer-mentoring program and implement friend-building exercises, while also developing curriculum to improve the coping techniques for victims.

“Victims who end up on the worst trajectory are the ones who think, ‘It was my fault. It’s nothing I can change,’” Echols said. So part of the program will be retraining victims to attribute the bullying more appropriately, which is Graham’s specialty. “It’s reframing our thinking. What are other possible reasons this could have happened?”

Aurora Middle Schoolers Carissa Simagna, 12, left, and McKinzee Malott, 12, are fast friends working together in Dr. Leslie Echol’s Peer Builder program.

Many antibullying programs focus on the bullies’ actions or the bystanders’ abilities to take action, according to Echols and Graham.

“These kids need something special,” Graham said. “We need the whole school approach, but we also need to focus on the particular concerns of kids who are themselves a victim.”

Web of connections

Echols is a former elementary school teacher who nurses a soft spot for kids who don’t fit in.

“I just want kids to be happy and have opportunities for friendship like everyone else,” she said.

But previous studies revealed that middle school students start being more selective with friendships. They seek friends who are similar to them. That could be students of the same gender, race or socioeconomic status, or those who participate in the same classes, extracurricular sports or clubs.

Echols completed a study with more than 6,000 California middle school students. She mapped current relationships, connections and commonalities among students.

“It ends up being this big spider web,” she said.

She used this social network analysis to see which students were most likely to choose a friend from another racial background.

At Aurora Middle School, Dr. Leslie Echols leads activities to encourage friendship formation.

“A white teen is less likely to choose a Black peer as a friend. She is most likely to choose a white peer as her friend,” she said. “My hypothesis was that a biracial friend, who shared the racial backgrounds of the Black and white friend, would be the most common bridge between the two monoracial youth.”

That hypothesis proved to be true. In fact, having a biracial mutual friend was the best predictor of choosing a cross-race friend for those in a cross-race friendship for the first time.

“Leslie has a unique, winning combination of skills. She is incredibly talented with sophisticated quantitative analysis,” Dr. Sandra Graham said. “More than that, she approaches sensitive issues and applies creative solutions.”

This builds on social network theory’s principle of transitivity, which says that having a mutual friend increases the likelihood of becoming friends with someone.

“Having a friend in common increased the likelihood of choosing any cross-race peer as a friend,” said Echols, who published the study’s results in Child Development.

Another strong predictor was how many classes students had in common.

Jadin Misner, 12, left, and Matthew Cutbirth, 13, work together in Dr. Leslie Echols’ Peer Builder program.

Encouraging friendships

Echols wants to break down barriers and encourage friendships.

A few years ago, she initiated a study at a diverse school district in Missouri, where about 40% of the population is Latino.

“This was a great opportunity for me to look at cross race friendships and intergroup relations in these schools that have changed drastically in the past 20 years.”

Her question: How could she encourage students to build cross-race friendships?

After assessing current beliefs and evaluating withstanding relationships, she paired students. Some students had a same-race partner and some had a cross-race partner. They set aside time to intentionally get to know each other by asking open-ended questions. After a few sessions, they worked on a task that involved communication and cooperation.

Through this program, Ashlyn Thurman, 13, left, and Aubrey Simpson, 13, have formed new friendships.

She saw real relationships develop. Even several weeks after the study concluded, surveys showed the participants ranked their partners higher among their friends and peers.

“I’ll never forget this one girl who came up to me afterward and said she’d met her soul mate, her best friend,” Echols said. “And it was someone she had gone to school with forever. She just hadn’t had the opportunity to really get to know her.”

The most promising part of the study: “There were no differences between the same-race and cross-race pairs in terms of closeness and friendship development.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Bob Linder

Further reading

Connections: Data and real life

Qiu, associate dean of the College of Natural and Applied Sciences and a geospatial sciences faculty member, asked a logical question: Why don’t people spread out more evenly?

She imagined streets with less congestion. It felt like the perfect solution.

But it’s never quite that simple, she learned. You have to consider infrastructure, landscape, natural resources and other factors. Variables like these can influence how people interact with their environment and where they choose to live.

“Two scientists can look at the same set of data and have different insights.”

Now Qiu gathers and analyzes data to better understand the connections between variables and outcomes. Recently, this work resulted in several publications about determining potential sinkhole sites based on the collection of new elevation data.

“We’re trying to understand this world in a fully contextualized way, based on all the data and the methods,” she said.

In addition to studies on hazard vulnerabilities, she’s also interested in land use, health and population estimation.

What thread connects her varied research interests? They each have a personal and societal impact.

Predicting MAP success

As a mother with an interest in math, Qiu proposed another research question: What was the greatest contributing factor to successful math scores on the Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP, test throughout Missouri?

You might wonder how this relates to geospatial sciences. She explains that the first law of geography says everything is related. Things that are near to each other are more closely related.

Since students within a school district are physically close together, they are affected by many of the same variables.

“Seeing trends can help us more efficiently use our resources,” Qiu said.

After obtaining scores from 516 public school districts, she identified variables that she suspected might play a role in MAP test scores. She surveyed teacher credentials and explored census data.

The work of Dr. Xiaomin Qiu has practical applications. She answers questions that can inform policy. Her research can also influence resource allocation – to make the biggest difference to the communities that need it the most.

Would teachers who held master’s degrees be correlated with the highest achieving students? If a teacher had a math teacher certification, would the students reach peak performance?

Or did the family demographics have a greater influence? Would average household income play a role? How would the frequency of single parent households play into the score?

What’s the biggest factor?

Unsurprisingly, previous related studies showed a student’s attendance, participation and homework completion correlated with better test scores.

“Success is strongly determined by personal characteristics, like educational values, confidence and participation in extracurricular activities,” Qiu said.

But analyzing the data made one thing clear: School districts with the greatest household income had the greatest scores.

“When the area has more wealth, public schools receive more taxes, making them a more attractive school to land quality teachers,” Qiu said.

Due to the relationship between higher pay and higher levels of education themselves, Qiu says parents in these areas are more likely to pay closer attention to their children’s academic performance.

“Right now we have so much data. We can take full advantage of the data and produce some meaningful results for people to use. I think this is very important in this field.”

Across the region, though, the significance of individual variables changed.

In the southwest Missouri area, for example, the greatest relationship to student proficiency was parental education level.

In contrast, the greatest influence on math scores for northwest Missouri students was the number of parents in the household, with two-parent households being associated with higher scores.

This proved that one solution wouldn’t improve scores statewide.

“In the end, this study can give policy makers and administrators a new way to think about what they need in different schools,” she said. “We know income, or other influencing factors, are going to be at play, but how big is the role right here? This way you can customize a solution – one that is effective and efficient for your needs.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

A tale of two bats: One lives, one dies

It’s not as simple as falling asleep and waking up in six months. Bats go into torpor, which is a physiological state, unlike sleeping, where almost everything is shut down. Bats live off their body fat during that time.

Dr. Tom Tomasi, professor of biology, studies hibernating animals in torpor, especially bats.

Some species of bats develop white nose syndrome. It sounds cute, but it is decimating the bat population. More than a million bats have died each year since it was introduced in the United States in 2006.

White nose syndrome isn’t directly lethal. Tomasi compares it to when people get a rash. However, the bats die during or shortly after hibernation from this fungal infection. This is because it causes them to use too many calories in the winter.

Many bats reside in a cave at Sequiota Park. Dr. Tom Tomasi participates in an event there in fall 2019 and uses it as an opportunity to educate the community on white nose syndrome and bats.

Two reactions

Tomasi attributes the declining bat population to two things: white nose syndrome and torpor.

Bats can’t be in torpor all of hibernation. Every so often, a bat arouses out of torpor. The heartbeat speeds up. The body temperature rises. The bat may find a better spot in the cave.

“Bat females generally produce one pup a year. If that pup survives, it’s going to take a long time to get back up where it needs to be.”

Some bat species that get white nose syndrome, like the tricolored bat and northern long-eared bats, arouse more often than healthy bats. The more they come out of torpor, the more body fat they burn. The bats that arouse more often run out of fuel and die.

Other species of bats, like grey bats and big brown bats, seem to ignore the infection and arouse at the normal rate. They fight off white nose syndrome in the spring when they end hibernation.

Drs. Tom Tomasi and Christopher Lupfer examine a bat at Sequiota Park.

Down to the genes

Why are some bats triumphing over white nose syndrome and others are dying at alarming rates?

Tomasi brought in Dr. Chris Lupfer, assistant professor of biology, to look at the immune system.

“We’ve been looking at whether or not the immune system will explain why some species are 75-95% gone,” Tomasi said. “Other species, their numbers don’t change.”

Together with students who work in their research lab, they found six immune-function genes that are expressed more in species affected by white nose syndrome.

Bats, like this one, are susceptible to white nose syndrome. Drs. Tom Tomasi and Christopher Lupfer are identifying the genes that allow some to survive.

The bats who are dying turn on those genes before or during torpor. The bat species who are surviving wait until spring to turn on the genes to fight the syndrome.

“The immune system of the susceptible species tries to turn on and protect the animal, which doesn’t work,” Tomasi said.

Lupfer has enjoyed combining his interests: immune systems and going outdoors.

“And the bats that seem to say, ‘all right, it’s grown on me, but my immune system is not going to turn on and try to defend myself until spring’ are the ones that survive.”

“Bats are cool,” Lupfer exclaims. “It’s been exciting to work with bats and get out of the research lab and into the fields and caves.”

Lupfer has partnered with Tomasi for the past three years. With more than 30 grants and 35 publications, Lupfer wryly observes that Tomasi has groupies.

“Everywhere we go, someone wants to pick Dr. Tomasi’s brain,” Lupfer said.

Volunteers work alongside the team from Environmental Solutions and Innovations to record data on the bats living in Sequiota Park.

What it means for the Ozarks

“We used to have 500-600 bats in a cave I looked at with the Missouri Department of Conservation,” Tomasi said. “When we were there a couple years ago, we found 45.”

Tomasi and Lupfer have traveled to Oklahoma, Utah, Arizona and other states to find and protect bats.

“So that same bat that survived the wintertime and repaired the wing damage, got rid of the fungus during the summer, the next winter when it’s going to hibernate, it could get it again.”

Lupfer adds that this research can prevent other areas from being as harmed by white nose syndrome.

“In the western United States, white nose is just starting to pop up,” Lupfer said. “If we can use our research to predict which bats are more likely to die, then wildlife managers can take steps to protect those bats now.”

- Story by Tori York

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Gawat

Further reading

Summing it up: Adding context to education

Livers, an assistant professor of elementary and mathematics education, studies how math classrooms fall into cycles of ineffective teaching.

“Math classrooms still look like silent rows of students with worksheets,” Livers said. “We know that’s not effective.”

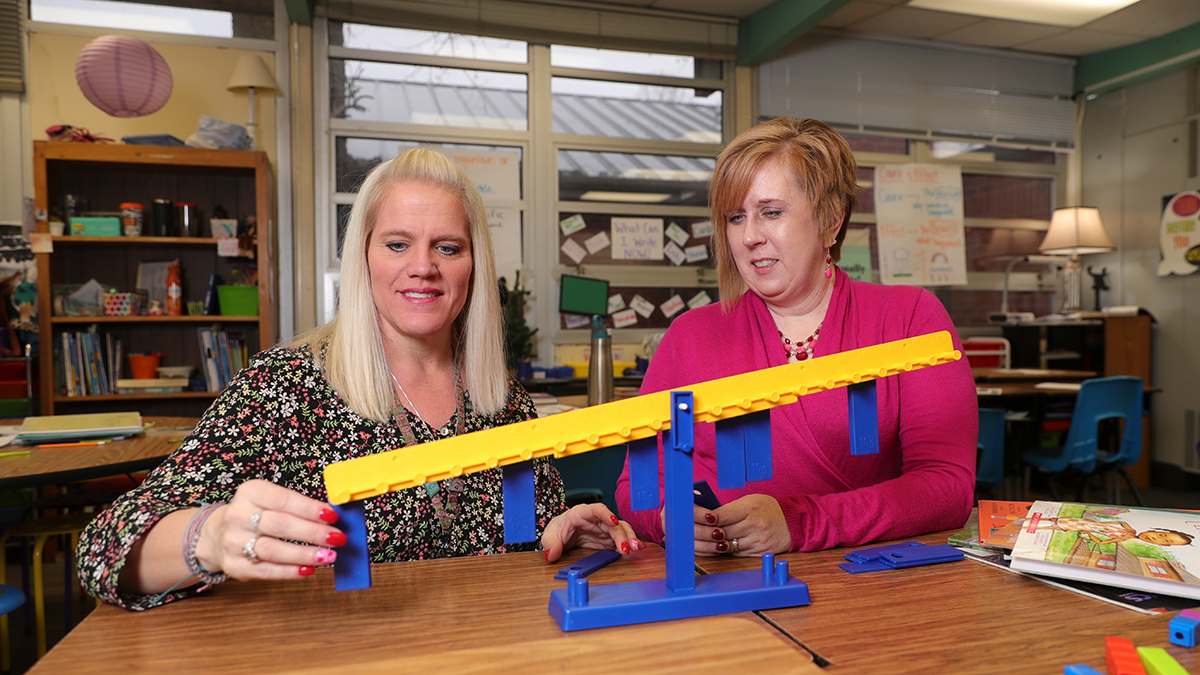

Dr. Stefanie Livers works with Amie Turner, a Mark Twain Elementary School teacher in Springfield. Turner wants to ensure she is reaching her students.

Livers studies the barriers that prevent math classrooms from advancing. For instance, in a recent National Council of Teachers publication, Livers and collaborators addressed the dangers of using animal tricks – like calling the inequality symbols alligator mouths – within mathematics instruction. These tricks distract. Instead, she says the focus should be on tasks with meaningful contexts.

“Dr. Livers is connected with the best math educators in the country,” said Dr. Tammi Davis, assistant professor of elementary education at MSU. “Her research guides her teaching, and she is constantly working to improve teaching practices.”

“All people are math people. They just might solve a problem differently than someone who processes faster.”

Creating ethical, confident teachers

Livers’ research has three main areas of focus. These include preparation of future teachers, professional development and coaching of practicing teachers, and equitable-based teaching practices.

For Livers, equitable teaching practices include providing meaningful context. This means students can better comprehend the meaning behind the concepts and procedures.

Equitable teaching practices, she says, also includes removing biases whether or not they had previously been recognized. Improving instruction can start when educators analyze their own elementary school experiences, she notes.

“Historically, schools and education are developed in a biased system. We know that teachers tend to teach in the way they were taught.”

About her research

The final piece to Livers’ puzzle for improving teacher preparation is self-efficacy. In other words, she’s asking how teachers become confident in a classroom.

One of her recent studies on this topic examined five areas: instructional strategies, student engagement, teaching problem solving, student-centered practices and classroom management. Current elementary teachers, secondary math teachers and special education teachers were asked to self-report on each of those areas.

Livers and collaborators from the University of Alabama and University of South Carolina noticed over all categories of teachers there was a correlation between those who felt confident in instructional strategies and student engagement. Efficacy was also noted when teachers felt strong in both their instructional strategies and teaching problem solving.

But student-centered practices didn’t fit the puzzle as well, and were only statistically significant among the elementary teachers.

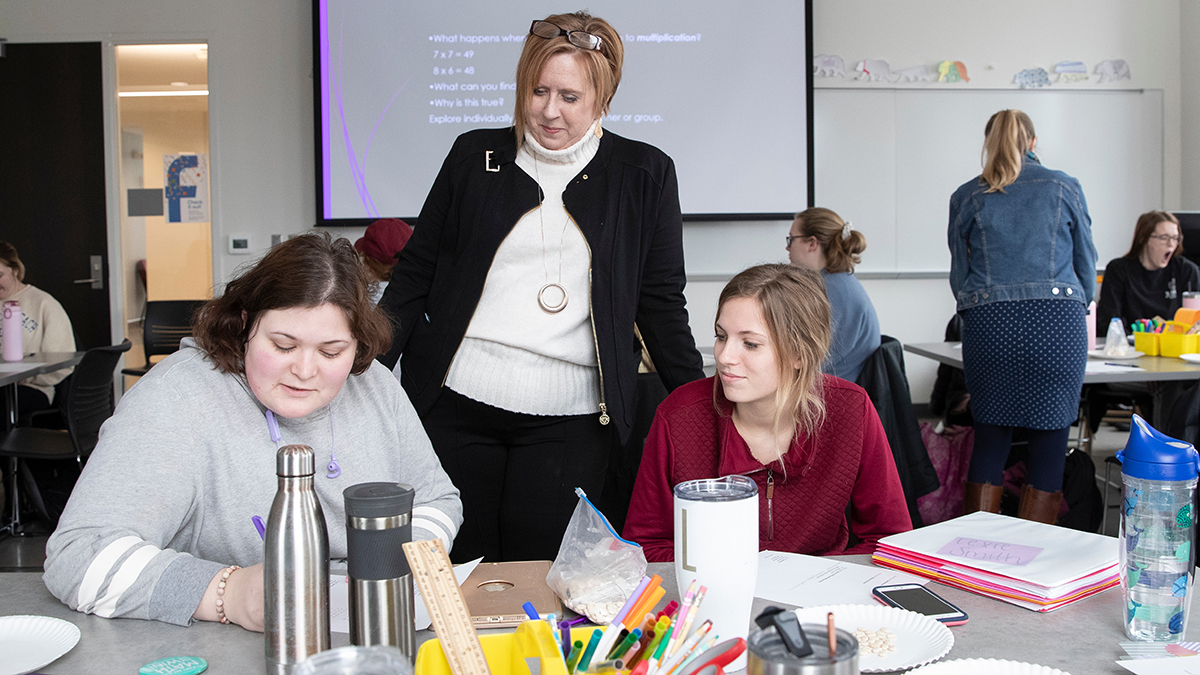

Dr. Stefanie Livers prepares education students to engage with their future students.

“Typically elementary teachers do plan and implement more student centered practices,” Livers said. “Student-centered math instruction allows for strong student contribution, encourages active student exploration, uses problems that require students to think critically and communicate their thinking, and asks students to explain the ‘why’ of their answers.”

Livers says that this published study can influence the future of professional development for practicing teachers.

“Because other research recognizes the interconnectedness between self-efficacy and teaching practices,” she said, “facilitators of professional development can learn from our findings to guide their collection of baseline data and to inform project designs.”

“The work I do pushes the societal misconception that there are math people and then there’s everyone else.”

You are a math person

“Mathematics is the gatekeeper for all careers and futures,” Livers said. “Many schools use math as a decision maker of what track or trajectory you’re on.”

If math serves as a gatekeeper, what about students that don’t excel in the current math classroom model? Livers argues that every student can solve problems by using their individual strengths and funds of knowledge.

“How do we do it better for our students?” Livers said. “If that’s looking at teacher self-efficacy, so they can have more confidence, I’m happy to do it. That’s going to affect student achievement which affects everything else.”

- Story by Abby Blaes

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Gawat

Further reading

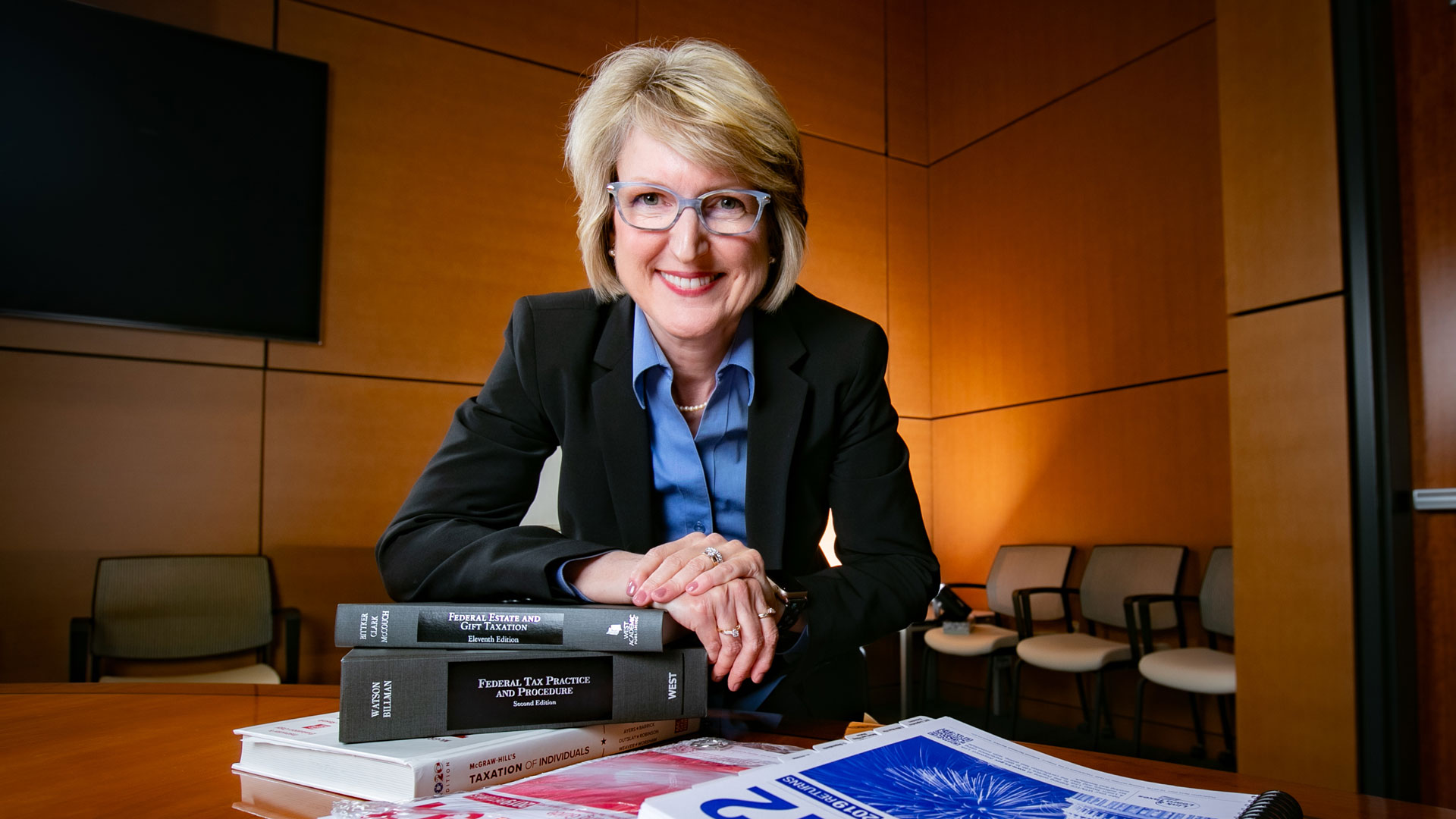

At the intersection of law and taxes

“There’s a myriad tax benefits that are automatically lost the moment someone selects married filing separately,” said Dr. Kerri Tassin, assistant professor of accounting.

Individuals forgo the Earned Income Tax Credit, the American Opportunity Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit, among others, she noted. Inequities like this are of particular interest to Tassin.

“This individual who has been abandoned, possibly with some children, may be suffering in many ways,” she said. “Then they are penalized on their tax return as well.”

As a lawyer and accountant, the majority of her research concentrates on the intersection of tax and law. The IRS Tax Code fits the bill.

“I can’t tell you how many people don’t even know those provisions exist.”

Making it fair

In 2018, Tassin won the Outstanding Paper Award from the American Accounting Association for a piece she contributed to the Journal of Legal Research. In it, she outlined many inequities she saw in current tax codes. Then, she proposed alternative policies that would be more equitable for taxpayers.

She surveyed state income tax policies and found that some made accommodations for people who were married filing separately. She discovered credits similar to the Earned Income Tax Credit or family related credits that could be applied even if they weren’t applicable at the federal level.

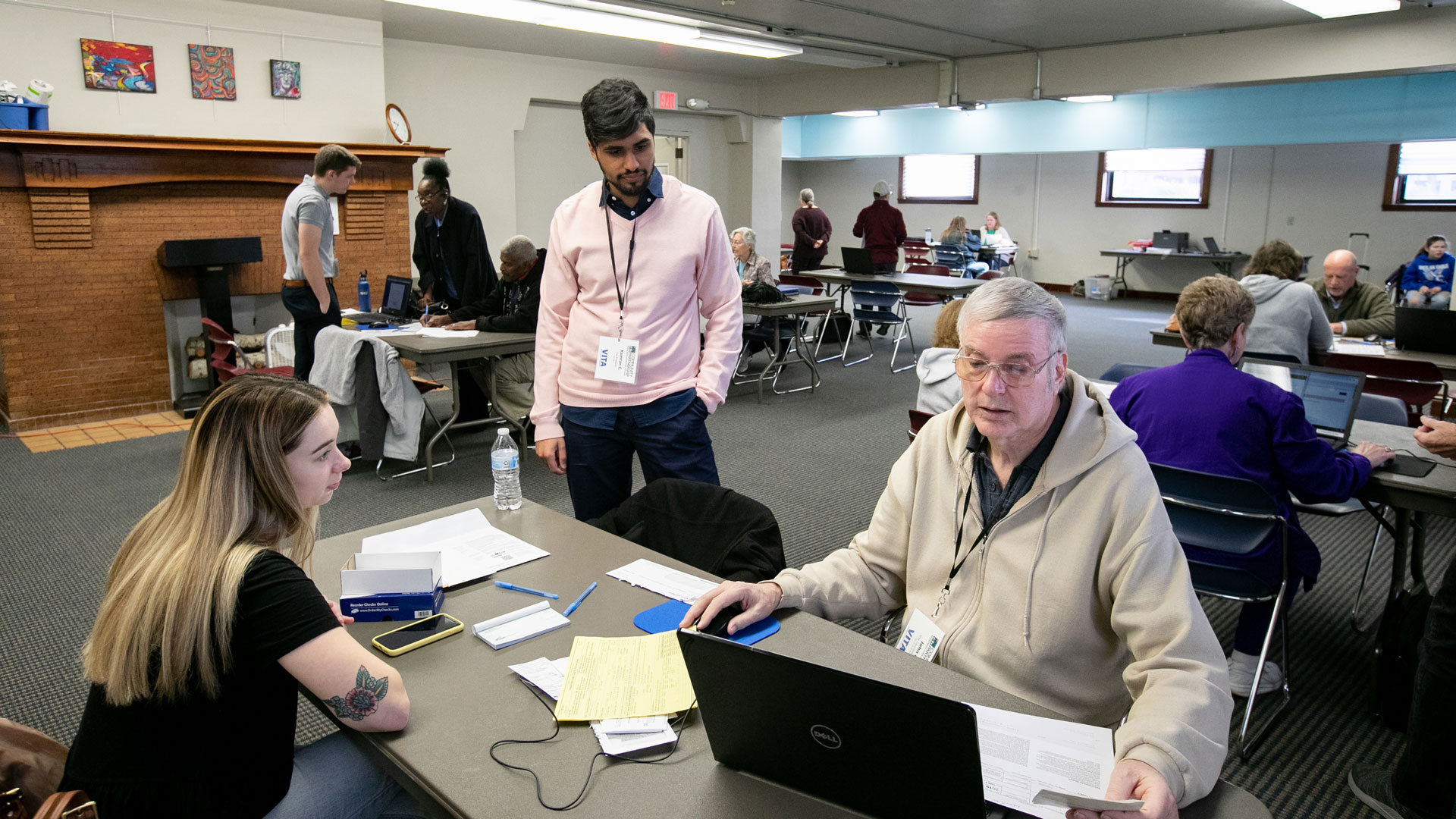

Dr. Kerri Tassin talks with John Carter as they oversee volunteer accountants preparing taxes for people in the community.

“Unfortunately, in a lot of other states, the state legislation piggybacks on the federal. If they can’t have the federal, they can’t have the state either,” she added.

Are you liable?

For that same article, Tassin also looked at liability incurred by taxpayers who filed jointly. This accounts for about 95% of married couples.

“Most married couples choose this option to take advantage of the tax benefits,” she said.

Tassin has produced 10 peer-reviewed journal articles on related topics in the last 10 years.

Dr. Kerri Tassin checks Matthew Wood’s work. He is a student volunteer at the income tax clinic.

She says most people don’t understand the legal implications of signing the return together. These couples incur joint and several liability, she said. Basically, if one spouse prepares the income tax forms and is trying to swindle the government, both signees are responsible for reparations.

“People don’t understand what kind of trouble they may be getting into with a spouse who’s cheating on their tax return.”

And if the cheating spouse disappears when the IRS comes calling, the innocent spouse will owe it all.

Giving to the community

Tassin, who received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at MSU, trains her students to participate in Volunteer Income Tax Clinics, which are sponsored by the IRS. In these clinics, the students prepare income taxes free of charge for qualifying individuals.

“Kerri establishes great rapport with her students and is conscientious about making sure they are fully prepared before we send them out in the community,” said Dr. Dick Williams, director of MSU’s School of Accountancy.

Kamran Choudhry, a student in the School of Accountancy at Missouri State, stands by as John Carter checks his work. Choudhry and Carter volunteered to prepare taxes with the Community Partnership of the Ozarks.

Few accountants, Tassin said, let alone her students, would be familiar with every state and federal statute. That’s why part of her policy proposal is to clarify the language “so there are no ugly surprises later,” she added.

“My heart is working with taxpayers in the clinics,” she said. The work is an alignment of her goals and passions. “I want to remove some of the fear and uncertainty.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Examining the Kurdish question from a historical lens

The late scientist Dr. Carl Sagan said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.”

This is especially true when it comes to understanding tensions in the Middle East.

Historian Dr. Djene Bajalan offers insights into the Middle East by exploring the region’s history. He focuses on issues related to nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

An assistant professor of history at Missouri State University, Bajalan’s main research area is on the region’s Kurdish community. In particular, he studies how Kurdish political activism developed within the Ottoman Empire before World War I.

To date, Bajalan, who has taught in Iraq and Turkey, has published more than 20 journal articles and book chapters, and a book about Kurdish history.

To people trying to learn history in America, it’s important to understand dynamics around the world so we can draw lessons from other places and make comparisons.

Why are the Kurds stateless?

The Kurds are the world’s largest stateless nation. They live across four countries – Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. They are the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East.

One of Bajalan’s latest articles is on the question of Kurdish statehood. It examines why the Kurds failed to secure a nation state after the Ottoman Empire collapsed post-World War I. The piece argues that while it seemed like the Kurds had a good opportunity for independence at the time, in reality, they did not.

One of the points I try to make is often what we see is the people who become nationalist it’s because of their experience; it’s not necessarily because they have a separate ethnic identity.

Bajalan claims the main reason was that the Russian Revolution in 1917 changed the geopolitical situation in the Middle East. The Russians’ withdrawal from the area where the Kurds lived allowed the Ottomans to reoccupy much of the Kurdish homeland in 1918.

“The loss of Russian patronage and protection was a major blow to the Kurdish independence movement,” he said.

Turning a thesis into a book

Bajalan is now working on his monograph. He hopes to complete it in 2020. The monograph is an extension of his PhD thesis on Ottoman history from 1839-1914.

The thesis covered the beginning of Tanzimat, a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire. It continued until the outbreak of World War I. Bajalan wants to add a final chapter. It will feature the rest of Ottoman history from 1914-1923, including the empire’s breakup.

Dr. Djene Bajalan has published more than 20 journal articles and book chapters, and a book about Kurdish history.

“This monograph is a broader study examining the rise of the Kurdish question. More specifically, it explores the rise of the Kurdish movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire,” he said.

Middle East political scientist Dr. David Romano says Bajalan’s historical work is vital.

“When we look at something as complex as human choices within a political system, there’s an important element conditioned by people’s historical memory and culture. These things develop over time,” said Romano, the Thomas G. Strong professor of Middle East politics at Missouri State. “Professor Bajalan’s critical research helps us understand the context people are coming from better.”

Adding to the body of knowledge

For Bajalan, his interest to study the Kurds stems from two things. First, his father is Kurdish. Second, he wants to address the lack of research about the Kurds.

I challenge the simplistic way that nationalism and the growth of nationalist movements are often looked at.

Before the 1990s, there were very few books on Kurdish history in the English language. There were even fewer books on the Kurds and Ottoman Empire.

“For a long time, this has been a neglected area of study in the Middle Eastern studies field,” Bajalan said.

He attributes the neglect to the political nature of the Kurdish question in the Middle East and the limited access to information. It is also because the Kurds do not have their own nation state.

Historian Dr. Djene Bajalan offers insights into the Middle East by exploring the region’s history.

“I’m part of a new wave of scholars studying various areas of Kurdish history,” Bajalan said. “One of the most exciting things about my research is every single document I come across is something no one’s written about. Even if people have seen it, they’ve not included it in their work.”

Through his research, Bajalan aims to highlight how and why identity and politics intersect.

“I want people to understand the complexities of identity and politics, and why some groups orient toward politics based around identity,” he said. “It’s not an arbitrary thing – it’s for historical reasons.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Jesse Scheve