Archive for 2021

Go with the flow

The associate professor of biology at Missouri State University makes his research and teaching understandable by comparing scientific processes to items you probably have lying around your house. A garden hose. Bottles of perfume. A paper towel roll.

It’s all in the name of working toward a solution that could save people who are born with congenital heart and vascular conditions. He has a simple central research question: How does the cardiovascular system form to begin with?

Congenital heart defects affect about 40,000 births every year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and congenital vascular anomalies affect nearly 1% of all births.

“If we understand the rules of how to build a blood vessel,” Udan said, “we could repair or even build vessels outside of the body.”

An expert in the field of cardiovascular development, Udan has published 20 articles and presented 25 times on the topic.

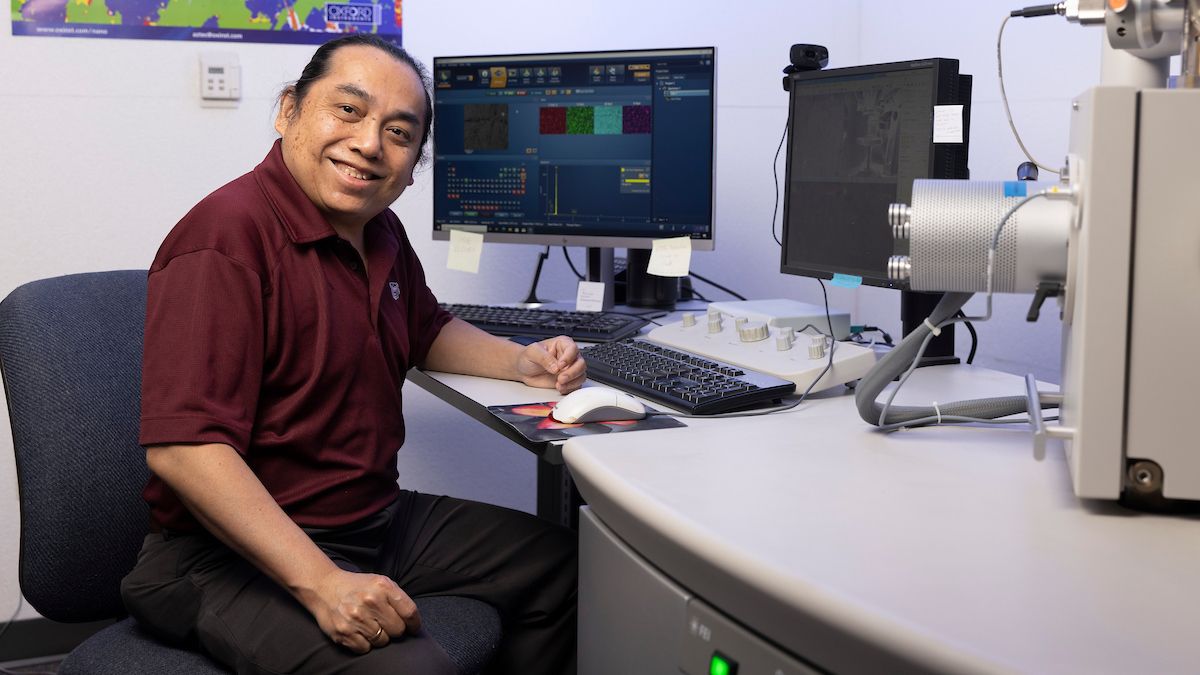

In Dr. Ryan Udan’s biology lab, he and his students research how blood vessels form.

A ‘magical’ event

Researchers know some about how the cardiovascular system develops in humans. The process starts as single cells connect to each other and form tubes. Then those tubes can connect to other tubes or branch out to form new tubes. But researchers don’t know everything.

“A scientist probably wouldn’t ever say ‘magic’ because there’s a reason for it. But yeah. Blood vessels are kind of magical.”

That’s why Udan and his team of student researchers are experimenting with embryos from several organisms, including zebrafish and mice. Drugs and substances can change the cardiovascular development of a mouse embryo, which provides useful information that translates to human beings.

Of particular interest: How do blood vessels close to the heart accommodate more blood flow than capillaries farther away?

First, vessels closer to the heart must get bigger in size. “They actually somehow magically come together and form a bigger vessel,” Udan said.

Second, the tissue that makes up these large blood vessels has to become thicker than capillary tissue.

“I think of it like a paper towel roll. The inner lining of the vessel is like the cardboard tube, and a bunch of paper towels that surround it are the extra layers of smooth muscle cells,” he said.

Students, like Gazi Shamita and Dailyn Jones, are integral to Dr. Ryan Udan’s lab.

Six-figure grant moves the needle

Udan knows that blood flow creates a mechanical force to tell certain vessels to get bigger and to form a thicker tissue. Udan compares the process to using a garden hose.

“When you turn on a hose, there’s pressure,” he said. “If you turn on the nozzle, water flows because there’s friction from the water against the wall of the hose.

“The same thing happens with these blood vessels. They get this mechanical force. That force turns on the genes, so they change themselves.”

Udan doesn’t know exactly how or why those cells decide to surround the larger vessel. But thanks to a $415,000 AREA grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, he will be able to conduct more research in that area.

“An embryo starts as a single cell. After a period of time, suddenly you see blood, you see a heart and that heart connects to those blood vessels.”

The hypothesis? High-force vessels send a chemical signal to tell smooth muscle cells to come over to that location.

“Imagine you walked into a room and somebody opened a bottle of perfume,” Udan said. “Even if you had a blindfold on, you’d probably be able to smell around until you found where the bottle is.

“We think those high-flow blood vessels are sending out molecules, which the smooth muscle cells sense, and move there. There’s a whole other thing we’re trying to study in terms of how it knows to attach to that vessel.”

Student Dailyn Jones conducts research in Dr. Ryan Udan’s lab.

Udan: Intelligent and kind

With the grant money, Udan will be able to pay undergraduate student researchers in his lab. He also has graduate student researchers who’ve worked with him on blood vessel research and participated in professional conferences.

“They’re actually learning how to do science,” he said. “Some of it’s physical, some of it’s mental and some of it’s organizational.”

Rachel Padget graduated from Missouri State in 2017 with a master’s in biology. She’s now pursuing a Ph.D. in translational biology, medicine and health at Virginia Tech and said she appreciated how much Udan cares about his students.

“Some of the techniques we used for our projects were very precise and delicate, and he was always patient with us and kind to us,” Padget said.

Udan stresses that lab time with the students is invaluable: “I really feel like I try to give them a comprehensive training experience.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Code talking: Shining a light on war-time heroes

Meadows, professor of anthropology and Native American studies at Missouri State University, works with many Native American tribes and cultures. He also studies Japan.

From a military family, early in his career he became interested with the military experience of indigenous peoples.

As he unearthed more about the ceremonies, music and art associated with these veterans, he discovered a largely unstudied area of history: code talkers from many Native American tribes. While the Navajo were well-known, over 30 other groups were not.

“I stumbled upon it myself,” Meadows said.

He was interviewing a Comanche World War II veteran, then in his 70s, when the man mentioned he served as a code talker.

“With the reality of mortality, I knew they wouldn’t be around to share their stories much longer,” Meadows said. “I dug in immediately interviewing all of the guys.”

As part of an ethnographic field school, students interview Vanessa Jennings of the Kiowa tribe.

This tenacity to uncover more and the humility to pivot directions to preserve important cultural experiences earned Meadows respect from many tribes, according to Vanessa Jennings. She is a Kiowa U.S. National Heritage Fellow.

“It is amazing to watch him record and document ancient information from these elders,” Jennings said. “Each bit is more information for the unborn generations to learn of our beautiful Kiowa culture.”

Dr. Bill Meadows takes his students to museums and memorials that honor Native Americans.

Congressional recognition

Much of what the general public knows about the code talkers’ contributions to military action has only been exposed in the last 20 years. This coincides with Meadows’ publications and the production of the film “Wind Talkers.”

“A lot of them had blessing ceremonies done before they left. Some carried traditional medicines into combat. They’ve shared the songs that were sung for them.”

In fact, Meadows testified before Congress in 2004. This contributed to the passage of the 2008 Native American Code Talkers Act. This act awarded congressional medals for all code talkers of both world wars.

Lobbyists distributed Meadows’ books to senators and representatives to educate and persuade them to provide recognition for other tribes. After hearing sufficient evidence, Congress can honor other groups in the future under the same act.

“The code talkers never went looking for this recognition,” it was their tribes, relatives, scholars and others, Meadows said.

After recently completing a book on WW I code talkers, he is working on a WW II volume.

With his deep roots in these tribal communities, he continues to receive tips. He hopes to identify and facilitate recognition for all tribes that participated – to make sure they are not obscured from history.

Decoding code talking

“Code talking allowed you to provide commands and plans on the open airwaves,” Meadows said. “Anybody could listen to it. But it was pretty much unbreakable.”

The languages were largely unknown, not written down and non-European based, he added.

Code talking entailed sending military communications in native languages. Some tribes also developed extensive coded vocabularies of newly formed words for military subjects, like tanks and artillery. At other times, they translated native words as alphabets to spell out proper names.

No matter which process was used, it saved hours of encoding and decoding. And in war time, hours saved lives.

None of the Native American codes were ever broken.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The Native American experience

Meadows evaluates more than how the tribes communicated. He also explores the ceremonies, myths, stereotypes and racism they experienced.

One of the most common myths was that all code talkers were sworn to secrecy. While the Navajo were, Meadows says dozens of newspaper articles widely shared information about other groups.

“I’m a collector and facilitator of information.”

Many today believe the code talkers weren’t U.S. citizens when they volunteered or were drafted in WW I. However, Meadows discovered that about two-thirds were.

He’s also been able to dispel the myth that all Native Americans in the world wars served as code talkers. Instead, they filled many ranks. Unfortunately, many had to confront the stereotype of the “super scout.”

“They were put in very dangerous positions and often told to take the lead. It was assumed they could run without making a sound and see better at night,” he said.

Fighting stereotypes

In the Pacific Theater of World War II, code talkers were treated well and even admired in their units. However, some were mistaken as Japanese and captured by other U.S. troops when not with white soldiers.

“Without the internet, travel and cultural awareness we have today, American Indians, Chinese, Korean, Filipino and even some Hispanics were confused as Japanese.” In the Pacific during WW II, “almost anybody that didn’t look European was confused as Japanese,” Meadows said.

All were eventually identified and released. Some had bodyguards assigned to prevent misidentification.

Dr. Bill Meadows overlooks a student field trip learning about Native Americans.

Relationships and recognition

“Dr. Meadows has provided both the Indian and non-Indian worlds with a small piece of written history that was only known through oral stories,” Lanny Asepermy said.

Asepermy is Comanche, a retired Master-Sergeant of the U.S. Army and Vietnam veteran. He has known Meadows for 20 years.

Meadows feels gratified that his books, along with the Native American Code Talker Act, will ensure Native American veterans will be remembered.

For him, the relationships and the cultural recognition make the job as worthwhile as the day he started.

“The Comanches gave me a Pendleton (Grateful Nation) blanket, which has stripes of all the military campaigns,” he said. “They said, ‘We have never given one of these blankets to a non-veteran. You’re the first and you’ll probably be the only one.’”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Going viral: Surveying the risk of transmitting disease

If you ask Dr. David Claborn, you’ll learn they have more influence than you think.

Disruption of land affects inhabitants’ health

Throughout his career, Claborn, director of the Master of Public Health program at Missouri State University, has studied the public health implications of disrupted environments, which are land or populations damaged by disasters. They create unstable living conditions.

“Instability quickly disrupts infrastructure, leading to either disease or some other kind of disruption to public health.”

A disrupted environment can include land damaged by natural disasters, like earthquakes and hurricanes. Or by human hands, like war and terrorism. But these visible disasters aren’t the only factors that lead to instability.

“An invasive species — like a weed, insect or disease agent — can also seriously disrupt an environment,” Claborn said. “That’s where my research comes in.”

To get a full picture of what species exist in Missouri, Dr. David Claborn has traveled all over collecting data.

Insects and infections

Claborn’s first research interest is entomology — the study of insects. This work crossed over into public health territory when he was commissioned in the U.S. Navy in 1988 as a medical entomologist. During his various deployments, Claborn was exposed to many areas changed by invasive insect species.

The Zika virus, carried by various species of mosquitoes, is a recent example of invasive insects affecting public health.

The problem: No one knew what kind of mosquitoes were buzzing around Missouri.

So, from 2016-19, Claborn led a team across Missouri collecting mosquito species. The Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) funded the research to calculate the risk of Zika in Missouri.

Since specific species are more likely to carry the virus, the DHSS needed a wide-scale count of the mosquitoes populating the state.

The Woodlands, which was acquired by the Darr College of Agriculture in 2013, has grown wild – making it a perfect location for research.

Research in the junkyard

Over four summers, Claborn and groups of students collected, identified and curated over 50,000 mosquitoes. They stomped through wreckage yards and old tire piles to extract samples.

Those locations may seem odd, but stagnant water and swampy conditions show up in the places you don’t expect. Mosquitoes love tire piles.

“Some mosquitoes are well-adapted to artificial containers because they’re well-adapted to living with humans,” Claborn said. “A wreckage yard is perfect breeding ground.”

The team lured mosquitoes with dry ice, then took them back to the lab to identify. The process had to be quick for the volume of mosquitoes and the scope of the state.

They ended up finding no specimens of the Yellow Fever mosquito, which is the main transmitter of Zika. Yellow Fever mosquitoes used to be abundant in Missouri. However, they did find two other invasive species that may have influence in the state.

“No one had looked at the mosquito fauna in Missouri for about 75 years.”

The first species, which Claborn believes displaced the Yellow Fever mosquito in Missouri, is the Asian Tiger mosquito. It also can carry Zika.

“This species is common, and it’s everywhere,” he said.

The second species is the Asian Bush mosquito.

“Both of these species became abundant in Missouri just over the last 20 years,” Claborn said. “These new species change our risk profile for the transmission of Zika and other viral diseases.”

The DHSS used Claborn’s data to form contingency plans. With his help, the state is prepared for a potential Zika, or other mosquito-borne virus, outbreak.

In addition to Dr. David Claborn’s work with mosquitoes, he is also studying tick populations.

Speaking of viral diseases

In spring 2020, Claborn’s work was disrupted by a new public health emergency: the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Claborn was on the MSU COVID-19 crisis management core executive team, which activated March 2, 2020. Using his experience in public health, he helped lead the asymptomatic saliva testing on campus.

Claborn wrote the testing questionnaire, collecting demographics such as living situations, age, race and other variables. The testing team compared positive tests with the demographic data, looking for patterns affecting disease transmission.

The pandemic highlights Claborn’s earlier point: Environments are disrupted in many ways. Educated, flexible public health experts are always on guard for the next health emergency.

“Four years ago, the main concern was Zika, but the nature of public health is that the main health concern can flip on its head very quickly,” Claborn said. “You have to be prepared to go do what needs to be done.”

- Story by Lauren Stockam

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Further reading

Our genders, our emotions

Dr. Elizabeth King, a Missouri State University College of Education professor, researches the learning environments of early childhood students. One area she investigates is how teachers talk about emotions with young children.

King believes gender plays a major role in our social-emotional development.

“The ways we talk about emotions with young children is affected by and affects our views of gender,” King said.

“Our views of gender influence who we allow to experience and express various emotions. That changes how we talk about emotions with children.”

Dr. Elizabeth King interacts with a group of children in Missouri State University’s Child Development Center. In her research, she discovered preschool teachers tend to minimize preschool boys’ negative emotions.

Emotion language

In a 2020 study published in Early Childhood Development and Care, King examined 112 toddlers across 27 different preschool classrooms in North Carolina. She first asked teachers to assess students’ social-emotional competence through a questionnaire. Then, King watched the young children in action.

“I just recorded the interactions of the teachers and children just how they would be — not in any specific type of activity,” King said.

King later watched her recordings and began coding teachers’ emotion language. Most of it fell into one of four categories:

- Labeling: Definitive statements about emotions, such as, “I feel happy.”

- Questioning: Questions to determine how another is feeling, such as, “Are you sad because you can’t find your toy?”

- Explaining: Statements that bring reasoning to emotions, such as, “I think you feel angry because you can’t go outside.”

- Minimizing: Dismissive statements toward emotions, such as, “Don’t cry. You’re okay.”

Finally, after classifying emotions on a pleasure to pain scale — with emotions such as excitement on the pleasure end and emotions such as sadness on the pain end — King viewed the recordings again. This time, she studied which emotions teachers addressed of male versus female students.

Observations from preschool playtime provided much of the data Dr. Elizabeth King needed for her recent research projects.

Unconscious bias

King’s findings ultimately aligned with her predictions.

“When teachers talked to boys, they most often talked to them about their negative emotions,” she said. “They’re actually minimizing boys’ negative emotions and saying things like, ‘You’re okay. You’re fine. Don’t cry.’”

King also discovered teachers’ tendency to encourage girls to show more positive emotions.

“Often, teachers socialized girls to be these smiley rays of sunshine,” she said.

“They commented on girls’ expression of happiness and said things like, ‘Now you’re happy! You’re really enjoying that music.’”

King doesn’t blame the teachers she observed. She understands the biases toward the ways we think others should show emotion are deeply rooted in our ideas about gender roles.

“We expect boys to be strong and girls to be positive,” King said.

She stresses the importance of teachers addressing these biases — and reflecting on the ways they respond to emotions.

What was her study’s discovery? The use of more emotion-minimizing language was associated with lower levels of social emotional competence in boys. The same relationship did not exist for girls. In short, dismissing boys’ emotions may hinder their ability to practice social emotional skills.

How does emotion language change when speaking to different genders? How does it change when speaking to children of different races? These are some of the questions Dr. Elizabeth King answers with her research.

Nuanced research

Studies regarding emotion language are relatively new, according to King. In fact, she’s among the first researchers to study the emotion language of teachers and how it changes according to the gender of students.

King has big plans for additional emotion language research. In fact, she published studies on teachers’ emotion language in both 2015 and 2018, too. She’s also interested in seeing how teachers’ emotion language changes when talking to students of different races.

“If we assume negative emotions from certain groups — like Black men, for example — are stronger than if a white woman were expressing them, that has implications for the safety of Black people,” King said.

She also wants to spearhead community-engaged research.

“That’s where I go into the field and work with teachers to reflect on and develop their practices,” King said.

For now, King is focused on her role as program coordinator for Missouri State’s early childhood and family development graduate program.

“We’re trying to update our standards for students and the ways we mentor them,” King said. “We want to ensure that we’re keeping the rigor, but also providing academic support they really need.”

Due to COVID-19, King couldn’t collect data for more research in fall 2020. Instead, she used the time to catch up on reading.

“I always need to buff up on what’s been done recently. I need to make sure I know exactly where we are as a field in order to situate my research” King said. “There’s so many questions you could ask.”

- Story by Sydni Moore

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Finding harmony

Dr. Cameron LaBarr’s goal for his students in Missouri State University’s choral studies program is that they connect so deeply with a performance that it just clicks, that they feel it in their souls.

The question that drives his rehearsals, performances and interactions with students is: What actions can cause those special moments and connections to happen?

The associate professor and director of choral studies has taken his students on performance trips across the country and around the world. He has authored books, conducted choirs on five recordings, guest conducted and adjudicated choirs internationally, and edited more than five dozen pieces of choral music for publication.

Choral students rehearse for one of many upcoming performances.

Friends from overseas

LaBarr wants his students to do more than simply sing the notes and words printed on paper.

“I try to not refer to the piece of paper as ‘the music,’” he said. “As musicians, we have to know and follow everything that’s on the page. However, there is so much that isn’t written down that we must understand in order to create a true connection with people.”

Part of that connection comes from welcoming international students into Missouri State’s choral family. Currently, this includes students from South Africa, China, South Korea, and Venezuela, with another student on the way from the Philippines.

“You’re painting a picture with the music and the text. It isn’t acting. It isn’t artificial. It’s all genuine and real. Everyone’s all in,” said Chandler Cooper, alumnus.

The opportunity to recruit international students comes when LaBarr is guest conducting abroad and when he takes his students on global performance trips. They’ve visited China, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Italy, Ireland, and South Africa. Those trips – especially those to South Africa – have inspired LaBarr’s teaching and work.

“From a research perspective, my travels to South Africa have brought a lot of ideas about African culture and music to what I do, to what I know and what I teach,” he said.

He edits and curates the Cameron LaBarr Choral Series for two music publishers based in the United States. The series features new music from across the world, including South African music.

“Because of the choral series, people around the world are able to know South African choral music more intimately, music which is normally only performed well by South African choirs,” LaBarr said.

“We found a way to notate the music and provide translation and pronunciation guides for the text. That has made the music more accessible to choirs and has helped them understand the cultural context.”

Dr. Cameron LaBarr conducts rehearsal in Ellis Hall’s C. Minor Recital Hall.

Welcoming environment

LaBarr has also welcomed international guests to his rehearsal rooms.

“It’s such a pleasure to meet students in other countries and open up a door for them. They just need somebody to say, ‘You’re talented and you clearly work hard, and we have an opportunity for you to go to college and join our program at Missouri State.’”

Graphic design alumna Olina Einarsdottir came to teach the choral group about her native tongue, Icelandic, when the students were rehearsing a song in that language.

“As a professor, I love the opportunity to turn into a student in those moments,” LaBarr said.

Those visits are all in the name of helping LaBarr’s students connect more deeply with the music they’re performing.

“Often, we’ll sing through a foreign language pieces and it will trigger some sort of strongly-felt emotion,” he said.

Chandler Cooper, a 2018 music education alumnus, sang and studied in the choral program from 2016-2018. Now the choir director at Republic High School, Cooper said he can see LaBarr’s influences come out in his own teaching.

He particularly remembers LaBarr’s attention to detail.

“He always says those fine elements matter, even the design of your printed program at concerts,” Cooper said.

“His impact on me and everyone else who’s had him really is immense. As soon as people figure out what they want to do with their lives, he does everything he possibly can to help them achieve that goal.”

Dr. Cameron LaBarr has authored books, conducted choirs on five recordings, guest conducted and adjudicated choirs internationally, and edited more than five dozen pieces of choral music for publication.

Spending time with a composing legend

Legendary composer and conductor Alice Parker welcomed LaBarr, his colleagues and students at her home in Hawley, Massachusetts.

LaBarr and John Wykoff, a composer and associate professor of music at Lee University, wrote a book about one of their journeys to Parker’s house. “The Melodic Voice: Conversations with Alice Parker” released in 2019. It includes 345 pages of transcribed and edited interviews with the 94-year-old. Parker counts more than 40 hymns, 47 choral suites and 33 cantatas among her works.

She conducts workshops for composers and conductors, many of which LaBarr and his students have attended. There’s no cell phone service and virtually no internet access in her hometown of 337.

Parker writes in a newsletter about crispy fall leaves seeming to talk to each other as the wind flits them around. It’s a setting that allows musicians like LaBarr to learn more about connecting with people through music.

“You stay at a farmhouse down the hill from her house, which is the old town hall,” LaBarr said. “Every day, you walk up the hill, sit in her studio around the table, sing, learn and enjoy meals together.

“I think a lot of that environment influences her music. One of the biggest things I take away is how to ‘get music off the page.’ What that turns into is living a life of music and community. You’re aware. You’re listening to the souls around you and to your own.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Celebrating collaborative research

Sakidja is a professor in the department of physics, astronomy and materials science at Missouri State University, the nation’s only such combined department.

Computational materials science uses modeling, simulation, theory and informatics to better understand materials.

Sakidja’s research is varied, but his ultimate goal is the same.

“Our overall research goal has been to help accelerate the discovery process of and to design new materials. We employ computational materials science to achieve this goal,” said Sakidja, an Indonesian native.

He is involved in multiple grant-funded collaborative research projects with level–one research universities (R1), the highest Carnegie classification. The projects have received nearly $2.9 million total in grant funding from the Department of Energy (DOE) and National Science Foundation (NSF). More than $1 million was granted to Missouri State.

Dr. Ridwan Sakidja prepares his equipment for an experiment.

Interesting research

One example of Sakidja’s research is a multi-scale modeling project. In it, he and his collaborators are predicting the performance of a nickel-based superalloy for turbine engines.

The goal is to develop new materials for turbine engines to operate at higher temperatures but with less energy and at a reduced cost.

The project is supported by the DOE and is a collaboration with UMKC, Missouri University of Science and Technology, and University of South Carolina.

“We work together to design and predict the mechanical properties of the next generation of superalloys,” he said.

This collaboration is possible because of supercomputer clusters. Sakidja and his graduate assistants perform critical virtual experiments on the supercomputer clusters.

The alloy system is very complex, made of 10 elements and contains multiple phases. The modeling is key because it’s incredibly expensive to conduct experiments to develop new alloys, he explained.

Mechanical failures typically originate from the breakdown at the atomistic or molecular level. So, understanding the dynamics of the mechanical properties at this level is critical.

“Our main contribution to this project is to develop the modeling platforms that can be used for materials development by leveraging our computational research experience,” Sakidja said.

Their collaborative work has been peer reviewed and published in SpringerLink, IOPScience and Nature Partner Journals.

The first two graduate assistants who worked on the project have already moved on to PhD programs at the University of Pittsburgh and North Carolina State University.

“Dr. Sakidja was a wonderful mentor who helped us find a problem, critically analyze a problem and solve it. This research was beneficial because it gave us real life experience that we would encounter in jobs after graduation. The research greatly helped me in PhD admission,” said Rabbani Muztob, who is pursuing a PhD at University of Pittsburgh.

Preparing graduate students is a priority for Dr. Ridwan Sakidja.

Collaboration is key

For another project funded by the NSF, Sakidja works with UMKC and Ohio State to develop a material used in body armor. The goal is to produce body armor at a lower temperature and reduce the cost of manufacturing.

“Good research draws the attention of the world toward the university, helps promote the professional excellence of the faculty, accelerates the development of the university and attracts outstanding students. The research I conducted during my master’s at MSU helped me to get into the PhD at another top-rated university,” said Sabila Kader Pinky, PhD student at North Carolina State University.

Typically, these materials are manufactured at 1,500 degrees Celsius, consuming an incredible amount of energy.

“The low-temperature process that we helped model offers an alternative route that dramatically reduces the necessary temperature to less than 300 degrees Celsius, a significant saving in energy and thus operating cost. Within this project, we also advanced the use of machine learning to help optimize the low-temperature synthesis process. This was why our project has been funded as a part of a special grant from NSF called Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future,” he said.

Their collaborator at Ohio State characterizes the materials via a state-of-the-art scanning transmission electron microcopy. Then teams at UMKC lead the effort to fabricate the new materials and overall design.

Sakidja is also working on a project with the University of Kansas funded by the NSF to develop advanced electronics device called tunnel junctions.

“Our part is helping design the device by modeling the synthesis process at atomistic scale,” he said.

The project supports both undergraduate and graduate students as research assistants and graduate assistants.

One of Sakidja’s students, Devon Romane, contributed to a recent publication in The ACS Applied Materials Science and Engineering Journals. Romane finished his bachelor’s in physics in 2019 and is enrolled in the materials science graduate program as a graduate assistant.

Romane modeled the layer-by-layer deposition/synthesis process at the atomic scale the critical segment of this device, namely the ultra-thin tunnel barrier. Thickness is only about a few nano meters. Think of nanometer scale in terms of the diameter of a typical human hair being split into 100,000 pieces.

Without collaboration, much of this research would be impossible because the equipment costs would be prohibitive, said Sakidja.

He also hopes it will help recruit top talent to MSU’s graduate program.

“Computational material science is one of the best return of investments,” Sakidja said. “My hope is students can see this is the best place for them if they are into computational materials science. To be able to hone your skill, to excel and to participate in research at a university that is not as cost-prohibitive as others.”

- Story by Juliana Goodwin

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Changing the look

Runway models, social media influencers, pageant queens, celebrities and even Barbie purport these troubling ideals. They are almost unequivocally identified as beautiful, as evidenced by the money we spend and who we choose to idolize.

You can also see young girls internalizing these standards as cheerleaders scrutinize their bodies, wear revealing uniforms and undergo mandatory weigh-ins.

Dr. Brooke Whisenhunt has studied media influences on body image for more than 20 years. As a professor of psychology at Missouri State University, she works alongside her colleague, Dr. Danae Hudson, leading a lab of graduate and undergraduate students to research this and related topics.

“Media images are powerful and convince women they should be smaller than even what is healthy,” Whisenhunt said. “Women become chronically dissatisfied with their current body size, which has actually been increasing in America. Meanwhile, the ideal body size has decreased.”

She has written, co-authored and presented extensively on this topic, often letting her students take the primary authorship.

“What kind of images are we putting out there for young girls, teenagers or women, that gives them a sense that their body isn’t perfect as is?”

One recent study led by Whisenhunt’s former graduate student Frances Bozsik gained national attention. The team proved over time the ideal has become not only taller and thinner, but also more toned and muscular.

“It is an added impossibility,” Whisenhunt said.

Media images convince women they should be smaller than what is healthy, according to Dr. Brooke Whisenhunt.

Body ideals

Decades ago, Dr. Rick Gardner from the University of Colorado gathered historical and contemporary images of pageant contestants and Playboy centerfolds. He also collected height and weight data to examine body-image ideals. The study exposed that over time, ideals evolved from thin to thinner and taller.

Bozsik built upon that research, and Whisenhunt says they modeled much of the study to receive parallel comparisons.

For their study, they chose to use photos of Miss USA winners during the swimsuit competition. They altered photos to obscure contestant faces and changed all swimsuits to black. By editing the images, the team tried to remove biases of different swimsuit trends.

While height and weight data are no longer available for these contestants, study participants evaluated 15 years’ worth of images. They ranked photos in terms of fitness, attractiveness and muscularity.

Across the board, Whisenhunt and Bozsik found the more recent winners were rated higher in thinness and muscularity.

“It provided us with evidence – at least visually – that the more recent winners looked thinner and appeared more muscular,” Whisenhunt said. Because the photos showed beauty pageant contestants, it’s understood that these women were considered attractive, noted Whisenhunt. “These women are the expression of what we say is ideal.”

Is it attainable?

To further test how muscularity equates with attractiveness, Whisenhunt’s lab found images of attractive, thin and muscular women. Then they did something no self-respecting influencer would do – they Photoshopped out the muscle tone on most of the pictures.

“Women as a whole are not great at reminding ourselves these images aren’t real.”

Study participants directly compared images and relayed the photos they found most attractive, Whisenhunt noted. Women highly preferred muscular images over the ones that were thin only. This further confirmed the hypothesis that muscularity is now part of the ideal.

“We expect women to restrict eating to get really thin, but now we also expect them to build muscle, which is very contradictory,” she said. Beyond it being unrealistic, she said, “the real kick is that it’s touted as healthier, making it harder for women to reject the notion.”

Along with her colleague Dr. Danae Hudson, Dr. Brooke Whisenhunt runs a research lab in the psychology department.

Improving the learning experience

In addition to systematically looking at the relationship between media and body image, Whisenhunt is passionate about improving student learning experiences. One way she’s done this has been to provide robust research experiences for the students in her lab.

Another way is by partnering with Hudson and Dr. Christie Cathey to reimagine MSU’s general education psychology course.

They redesigned the course to have fewer, larger sections. Each section would have several graduate and undergraduate assistants. Each plays a role in student success.

“How do you make a large class feel like it’s a small class?” Whisenhunt asked.

One way is to send personalized feedback after assignments and tests, she noted. The student learning assistants help in this undertaking. Meanwhile, they’re also learning about being effective teachers.

“Dr. Whisenhunt decided to pivot her research focus around the time that I worked with her,” Bozik said. “I don’t know that I ever told her this directly, but it was exemplary modeling of being free to make a career shift to better fit your interests and desires.”

Whisenhunt, Hudson and Cathey know the course is working in this new model, too.

“We’ve dropped the DFW rate – those who receive a D, F or withdraw from a course– by 10%,” she said. “That’s 250 students who are now successfully completing a course each year that wouldn’t have before.”

This data driven approach has given them more to write about, publishing seven articles on this work in as many years.

“Learning is not something I can force my students to do,” she said. “But I think we’ve shown that you can design a class in a way that maximizes the chances they will learn. You learn when you’re really struggling and dig deep down inside trying to figure something new out.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle

Further reading

Improving the lives of kids with autism

Wandering and bolting are both considered eloping – a term used for leaving an area without permission. It’s a problem behavior, especially for children with autism.

That’s why Dr. Megan Boyle, associate professor of special education at Missouri State University, researches the whys behind this largely understudied behavior.

She’s a board-certified behavior analyst, runs a clinic for children with autism spectrum disorders and prepares the next generation of educators for behavior issues in the classroom.

Boyle dives deep into this behavior.

“Some kids will take off, while others just kind of walk off and wander away.”

She wants to empower caregivers with practical and sustainable treatment options to prevent elopement rather than physically intercepting the child before escaping from view. She also wants to give children an outlet for obtaining the same sensations they seek without leaving the safety of their environment.

“Elopement as a response form hasn’t been acknowledged for how unique it is,” Boyle said. “If we recognize bolting is fundamentally different from a lot of other behaviors we deal with, we can improve how we’re treating it.”

Dr. Megan Boyle works with a young child near the entry of her clinic.

Why kids elope

Boyle’s elopement research identifies the reinforcement children seek by bolting.

“With elopement, you could have four kids who bolt for a variety of reasons,” she said. “So their treatments are all going to look different.”

“I think as a field, we’re kind of missing some nuances about elopement.”

She classifies the reasons as:

- Attention-seeking: Caregivers naturally chase a child who is running away.

- Escaping a task, place or situation: Children with autism often want to escape a specific situation because it may be unfamiliar, unpleasant or overstimulating.

- Sensory seeking: A child may run because he or she enjoys the pounding of the pavement, the strain of the leg muscles or the wind whipping against his or her face.

- Accessing an object or activity: When it’s out of reach, bolting may seem like the only option.

Boyle noted that some kids bolt because they want a nearby object.

“In a waiting room, a kid runs and mom says, ‘Come back and I’ll let you have my phone to play your favorite game,’” Boyle said. “Or it could be a desire to get the balloon they see across the room or street.”

Reviewing the literature and treatment options, Boyle noticed a lack of understanding of these complexities.

“We are considering a lot of variables and aspects of real life that aren’t being incorporated into the research so far,” she said. “Before we can target problem behaviors for treatment, we have to understand the why.”

As a board-certified behavior analyst, Dr. Megan Boyle runs a clinic for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Communication is key

Recently, Boyle published an article on some tactics she used with an 8-year-old client. He eloped to engage in stereotypy, often called stimming in the autism community.

Stereotypy is a repetitive nonfunctional behavior. In the autism community, hand flapping is one of the most common examples.

“A lot of kids with autism engage in behaviors that look a little different. But for them, it provides sensory stimulation or reinforcement,” she said.

In Boyle’s study, the boy was fascinated with hinges and felt drawn to doors. He would open and close the door, look at the hinge, walk through the door, and elope to do so.

Challenges abound in the treatment of severe behaviors, Boyle pointed out.

“How can we develop a treatment that parents will actually use, but that is still effective?”

Prior to each session, Boyle provided pictures of all the doors in the clinic building to her client and asked which one he’d like to play with. After careful consideration, he’d select one.

To encourage functional communication, Boyle would require him to point to it, ask to play with the door and then stay 20 feet away from the door until given permission to play.

“It didn’t count as elopement because he asked and received permission. He would go play with the door for one minute,” she said. “Then we would guide him back to the office and start over.”

The next step was to deny a percentage of his requests – to delay gratification – a procedure called schedule thinning, that is conducted after the communication response is strengthened. Gradually, Boyle increased the effort required or lengthened the wait time before play time.

Learned behavior

You may think, ‘If he could reach the door, why would he ever wait?’

In this study, though, if he bolted without permission, he only received three seconds with the door before removal. The 8-year-old understood he got more time when he waited.

“We’re really good at treating behaviors in the clinical setting, but practitioners often feel much less confident on how to apply those skills in the school or home setting. It’s a next step for me to help others mindfully set up clinical settings to mirror more naturalistic settings.”

“Kids will learn. You have to be consistent and the difference has to be clear,” Boyle said.

Boyle and the client’s mother then tested it in more natural settings. They would chat in various areas around the building, keeping an eye on him while denying or delaying his requests. After many meetings, he began to wait five or 10 minutes surrounded by strangers and doors.

“We use reinforcement so much because it works,” she said. “It changes behavior. Feelings follow. Kids get happy when they can ask for what they want, and they get it.”

And that is her motivation.

“There’s nothing like working with a kid with autism,” Boyle said. “The world melts away. It’s all about improving a life by increasing access to wants and needs.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

Reading between the data

This is a question Dr. Seth Hoelscher poses to his students when he is teaching investments and disclosures.

“You’d give money at a better rate to the one you have more information on,” he said.

Hoelscher, assistant finance professor at Missouri State University, was working toward his MBA at West Texas A&M University when the financial crisis of 2008 hit. As many people lost money during the recession, he decided to learn as much as he could about finance and investments.

Now he teaches the subject while researching commodity markets, disclosures and corporate finance. In 2019, he received the College of Business award for Best Empirically Based Research Paper. He’s published over 19 articles and written financial advice for sites like WalletHub.

What influences investors

Many of Hoelscher’s articles focus on voluntary disclosures. Such disclosures involve a company releasing information beyond the requirement of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Disclosures include information about a company’s financial operations. They can include both positive and negative news, data and operational details that affect business. Investors then use this information to shape their expectations for a company.

“We try to solve answers in the literature.”

Hoelscher pairs standard empirical data with hand-collected data from financial disclosures to determine what certain industries do and do not disclose voluntarily.

“Disclosures tell us how the company is operating and if or how they are managing risks,” he said. “It also tells the investment community more about the future prospects of the industry as a whole.”

The information helps investors understand a company’s future cashflows and profitability. This knowledge ultimately affects where investors put their money.

Disclosures also can positively affect a company’s reputation in the marketplace. This usually translates into increased market share and customer loyalty.

For example, consumers who know why prices go up and down in certain industries may feel better about investing in certain companies within those industries.

When oil prices rise, gasoline prices skyrocket. When oil prices drop, gasoline prices drop slowly, like feathers.

Rockets and feathers

One industry Hoelscher studies is petroleum and crude oil.

He surveyed literature to assess how petroleum prices respond to increases versus decreases in oil prices.

“This is a phenomenon referred to as ‘rockets and feathers,’” he said.

When oil prices rise, gasoline prices rise quickly as well — like rockets — to reflect the change in prices. However, when oil prices drop, gasoline prices drop at a slower rate — like feathers.

“One item that makes the oil and gas industry unique is the large up-front capital costs to find, drill and extract the crude oil,” Hoelscher said. This affects supply, but not demand, which can create interesting price fluctuations.

For example, in 2020, COVID-19 caused a significant and prolonged downturn in oil prices.

“While reduction in travel and increased remote work didn’t affect the supply side, it did affect the demand side,” Hoelscher said.

Large price swings in an industry like this may lead to questions of speculation and price manipulation.

“You cannot simply increase or decrease crude oil production in the short term to match the current demand. It is not like turning on and off a faucet.”

However, the empirical evidence Hoelscher surveyed shows speculation does not increase volatility in petroleum product prices.

“Ultimately, consumers can feel assured that speculation is not driving changes to the price they are paying,” he said.

Asking the right questions

Financial research presents unique difficulties. Most researchers use the same databases to collect their information.

“You have to ask, ‘how can I go about answering a question that hasn’t been answered? Or how can I answer a question from a different perspective?’” Hoelscher said.

He emphasizes this process when advising students at MSU.

“It’s great for students to learn how to justify their assumptions when presenting reports and research,” Hoelscher said. “Because it’s something that they’ll most likely continue to do in their careers.”

Hoelscher knows he will have to continue asking the right questions to find new perspectives in his work.

“Because it’s a social science, you can’t control every aspect,” he said. “But you can be creative to come up with new ideas and approaches.”

- Story by Kristina Khodai

- Photos by Jesse Scheve