Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ category

Communicating across an ever changing landscape

As a corporate trainer and executive coach for a variety of organizations, Dr. Shawn Wahl, head of the department of communication at Missouri State University, trained individuals how to listen, communicate their needs, persuade co-workers and bosses, motivate teams and navigate through difficult situations with customers and clients. With this knowledge, he’s written five books to improve communication skills. The latest book, “Communication and Culture in Your Life,” was published in spring 2014.

In this book, Wahl describes the importance of a global perspective – understanding language barriers, accounting for cultural social cues (like a lack of eye contact being a sign of respect or a sign of low self-confidence) and treating all people with dignity and respect.

“If we’re talking about international business, there are certain principles of cultural competency that we have to have. And cultural competency is directly related to human communication in terms of the choices we make as communicators,” Wahl said.

His expertise is directly relatable to students just entering the workforce as well as those he trains in corporate and non-profit settings, which has included major health care networks and oil and gas companies to name a few.

“The themes and titles of several of my book projects include the phrases ‘in your life’ and ‘excellence,’” he said. “How can you use human communication research to expand your family, your professional situation, and landing a good job?”

Emoticons: the new nonverbal communication

Emoticons: the new nonverbal communication

In a world with more communication options than ever before, including Facebook, Twitter, text messages, Instagram, email and other social media avenues that pop up every day, Wahl explains that competent communication choices need to be stressed early and often. His book, “The Communication Age: Connecting and Engaging” released in 2013, looks at the qualities of good human communication over time and how to maintain those qualities when it’s being mediated through technological devices.

“Because we spend so much time looking at our smart phones, there are now some things that we do that serve as nonverbal communication within our text messages,” said Wahl. “Also, if we don’t respond to a text, time is communication. If we don’t respond right away, the recipient might get frustrated or wonder what happened.”

Traditional nonverbal cues include hand gestures, body language and eye contact, but when communication isn’t face-to-face, all of this can be lost. Physical visual cues like a frown or a smile, which are biological and immediate from birth, noted Wahl, are replicated in these new communication forms but need to be thought about carefully.

“Step back and think about it . . . if I send an email or text message, there are still positive and negative reactions associated with my communication choices. Just like if you roll your eyes in a face-to-face interaction, you can do those in social media, too, but is it responsible?”

Wahl’s other book projects include “Nonverbal Communication for a Lifetime” (2014, second edition), “Business and Professional Communication: Keys for Workplace Excellence” (2014, second edition) and “Persuasion in Your Life” (2013).

Getting the juicy details

According to Qiu, grapes host the largest number of viruses of any plant because it’s a perennial woody plant.

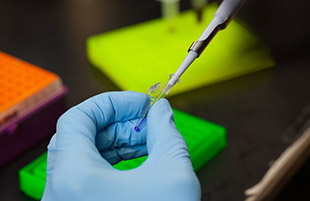

When a Missouri vineyard manager contacted Dr. Wenping Qiu in 2004 to express concerns about a disease plaguing his vineyard, Qiu speculated the decline was caused by a virus. Unable to find the link with known viruses after two years of testing, Qiu and his research team began utilizing a relatively new technology called RNA (Ribonucleic Acids) sequencing to decipher the sequences of small RNA fragments to piece together the viral genome.

It was in 2009 that Qiu, research professor in the William H. Darr School of Agriculture at Missouri State University, discovered the first DNA virus ever reported in grapevines, named the Grapevine vein clearing virus (GVCV). Though he was hopeful of a new discovery, he remained somewhat doubtful.

“We only found a small piece (of DNA),” said Qiu. “So my colleagues and I decided we have to find an entire genome of this virus before we can present the discovery to the public.” In 2011, after mapping out all 7,753 base pairs of DNA in the genome, they published their results.

Drawing a diagram, Qiu explained the complicated process of piecing together these fragments, designing primers from these fragments, sequencing them and searching for similar sequences in the gene bank. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, Qiu and others in his lab amplified the fragments out and repeated the process. They designed more primers, piece by piece, until the fragments overlapped and they knew the viral genome was circular.

“We sequenced thousands of those small fragments, and then we compared our fragment sequences with sequences in the gene bank. And then we found, ‘oh, this is new!’”

During the past 10 years, Qiu has been the principal investigator on numerous grants from the state and federal Department of Agriculture, leading to approximately $2 million in grant funding for his research. And all of that research stems from this interest in grapes.

But why grapes? According to Qiu, grapes host the largest number of viruses of any plant because it’s a perennial woody plant. Therefore, they are a great model for the progression and prevention of diseases. But DNA and RNA viruses multiply differently, so much research is still being conducted on how this virus multiplies and spreads over time.

“When a plant is infected by a virus, the plant tries to defend and protect itself against all types of viruses. It starts to cut the virus into small pieces. So in the infected plant cells, you can find the relics – or small pieces – of the virus genome.”

In recent years, RNA sequencing has been grabbing attention in the scientific community – it can be used to discover new viruses in other plants, animals and even humans. Discoveries of new viruses allow scientists and doctors to learn about how the viruses cause diseases and spread.

In recent years, RNA sequencing has been grabbing attention in the scientific community – it can be used to discover new viruses in other plants, animals and even humans. Discoveries of new viruses allow scientists and doctors to learn about how the viruses cause diseases and spread.

Through study of the GVCV in an isolated environment – in the Springfield laboratory as well as on Missouri State’s Mountain Grove campus, which is home to the Fruit Experiment Station, the Center for Grapevine Biotechnology and Mountain Grove Cellars – Qiu hopes to learn all he can about how to prevent its spread as it is quite detrimental to grape production in a vineyard.

Students dig deep into Grapevine vein clearing virus

Plant science students at Missouri State have unparalleled opportunities under Qiu’s supervision, who has been honored with an endowed professorship in agriculture by President Clif Smart and his wife Gail. The Grapevine vein clearing virus (GVCV) is the focus of two intense studies: one study is trying to discern which grape varieties are resistant to this virus; another study being conducted by graduate students Michael Kovens, LeAnn Hubbert, Shae Honesty and Ru Dai focuses on the genome of a new strain of the virus recently discovered in a wild grapevine.

“It’s important to find which grape varieties are prone to the virus and which ones aren’t because any varieties found to be resistant or tolerant to GVCV can potentially be used in breeding to prevent infection in those varieties that are more susceptible,” said Kovens.

Kovens is passionate about this work because he has seen the decline in quality grape production, noting symptoms such as leaf rolling, translucent veins, and shortened internodes, which eventually kill the vines.

“This study is crucial as the quality and quantity of the wine able to be produced is negatively affected by the virus,” he added.

A study being conducted by graduate students Michael Kovens, LeAnn Hubbert, Shae Honesty and Ru Dai focuses on the genome of a new strain of the virus recently discovered in a wild grapevine.

Walking through wild grapevines

Walking through wild grapevines

Missouri is known for its natural beauty and a wide variety of outdoor activities to enjoy. While out on a hike, you will likely stumble upon a bramble of wild grapevines.

“Wild grapes are everywhere in the Ozarks. Actually, in the 1870s, millions of cuttings of wild grapes were collected from Missouri and shipped to France to rescue their grape industry,” said Qiu.

While GVCV was first discovered in a cultivated, commercial vineyard, Qiu’s natural curiosity got him speculating about whether the virus might also be found in wild grapevines and what that would mean about the virus’ origin.

“We thought, maybe it is possible that this virus jumps from the wild grape species to the cultivated grapevines in the vineyard,” noted Qiu.

So he and his students collected samples of wild grapes and tested the virus on a particular wild grape species – Vitis rupestris. In one vine, GVCV was detected, which indicates it does exist in the wild. From there, Qiu and his research team sequenced the entire genome of the new strain and are now comparing its sequence to the one discovered in the cultivated grape varieties.

Hubert, another of Qiu’s students, accompanies him to Swan Creek to collect samples from Vitis rupestris to understand how it is transferred from one vine to another. One theory is that insects transfer the virus among wild vines.

A recent trip to Swan Creek found several vines showing symptoms of GVCV, so the team clips small vines, bags them with creek water and transports them to the laboratory. There they pot the plants, watch them grow and confirm if it has GVCV. Qiu noted, though, that the symptoms on the wild vines are consistent with those in the greenhouse, meaning they are most likely from the same virus.

Mapping the genome of Norton grapevine

Mapping the genome of Norton grapevine

Norton – the state grape of Missouri – makes a dry, deep red, full bodied table wine. It’s a hardy grape that survives despite temperature fluctuations and is naturally resistant to many diseases. Several years ago, Qiu and his colleagues at the State Fruit Experiment Station studied Norton’s resistance to one debilitating mold for grapes – powdery mildew. From there, they have expanded their research to begin mapping the genome of the Norton grapevine.

“When a fungal spore lands on the surface (of a Norton), it begins to germinate,” he explained. “But when it penetrates a plant cell wall, the Norton responds very quickly so that those cells that are attacked by fungal spores commit suicide – they just die.”

This hypersensitive response makes the Norton prepared for battle, ready to defend against outside agents.

“Indeed we found that the Norton naturally had high levels of these defense genes,” he said. “It’s a very fascinating phenomenon in grapes.”

Keeping an eye on grape research worldwide is important to Qiu. When he began mapping the Norton grapevine genome, he and the University came to a collaborative agreement with the French National Institute for Agriculture Research – an institution that was analyzing sequences of the Norton genome as well.

“We’ve collected the raw sequences of the Norton genome, and now we’re putting the puzzle together.” It’s a puzzle with millions of pieces, so mapping the entire genome of the Norton grapevine will take years, Qiu estimates. In comparison, the total length of the human genome is over 3 billion base pairs, which took the global scientific community 13 years to complete.

Growing and selling healthy grapes

Worldwide more than 5,000 grape varieties exist; however, in Missouri, about a dozen of popular varieties thrive. At the Mountain Grove campus, several vineyards boast grapes like Norton, Traminette, Chardonel, Chambourcin, Cayuga White, Vidal Blanc and Vignoles. These grapes are harvested each August to begin the winemaking process for Missouri State’s Mountain Grove Cellars to bottle and sell, but the vines have a greater purpose. Qiu is busy testing these grape varieties for presence of viruses – and virus-tested vines are being sold to vineyards with assurance of good health.

“We all want to learn more about new viruses. By studying this virus, we can develop some strategies for preventing this virus from spreading.” – Dr. Wenping Qiu

“Those seven grape varieties were tested and found to be free of 16 grape viruses. Those 16 grape viruses are serious viruses that affect grape production,” he said. “So when we sell these to grape growers or nurseries, at least they know those mother plants can be propagated free of these 16 grape viruses.”

A current project in Qiu’s laboratory is testing the resistance of a grapevine to viruses. How do they do it? First they test the grapevine to make sure it is healthy and free of any virus. Then, they graft the viruses onto the vines to see if these vines are able to support the viruses.

“This is something we are doing right now,” said Qiu. They hope to see that these vines are resistant, and then investigate the genetic basis for this resistance. “We all want to learn more about new viruses. By studying this virus, we can develop some strategies for preventing this virus from spreading.”

Making music in his mind

“There might be images or moods or characters that are suggested by the poetry, and I try to reflect that in the music I write,” said Murray. His piece “Tempest Fantasy,” on the CD “Spellbound” which was released by Navona in 2013 was recorded by the Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra based in Olomouc, Czech Republic. But its original iteration was vocal music Murray composed for a Missouri State production of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

“There might be images or moods or characters that are suggested by the poetry, and I try to reflect that in the music I write,” said Murray. His piece “Tempest Fantasy,” on the CD “Spellbound” which was released by Navona in 2013 was recorded by the Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra based in Olomouc, Czech Republic. But its original iteration was vocal music Murray composed for a Missouri State production of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

“I took a lot of the melodies I had written for that and transferred that to the string orchestra. So even though ‘Tempest Fantasy’ was not a vocal piece, it was the beginning for the orchestra piece.”

Murray composes all the time – sometimes taking four months on one piece – and plans to have an all vocal music CD released in early 2015. It will include pieces for solo voice accompanied by various orchestral and chamber instrumental combinations. Through New Music USA, he hopes to gain funding to assist in the travel costs associated with recording in the Czech Republic in summer 2014.

But he knows he’s one of the lucky ones.

“The biggest challenge for the composer is to get their music performed. This is especially true with orchestra. New music is not performed often,” said Murray. Many local and regional symphonies perform only one piece by a living composer during the course of a year. Instead, they tend to select primarily standard classical pieces from well-established composers. “There is not a lot of opportunity. To get performances of those types of pieces is very difficult.”

“The biggest challenge for the composer is to get their music performed. This is especially true with orchestra.” — Dr. Michael F. Murray

In his composition lessons, he critiques, gives suggestions, lends encouragement and talks about technical aspects of the music the students are writing. As with most writing, he says to “write what you know” – in this case, write for the instruments you’re most familiar – but the experience with the recording company, orchestra, producer, conductor and the licensing company proves invaluable to his students, too.

“That goes far beyond putting notes on a page and analyzing what it will sound like. All of the interaction I gained from a professional standpoint – from how to work with people and see that process all the way through to the end – is something I share with my students,” Murray said.

Perfect harmony: uniting feeling with fundamentals

Starting in elementary school, he began learning the trumpet and guitar, and by high school he was a bass guitarist in several rock bands. He’s also a trained singer and pianist. In college, he became interested in composition and changed his major from computer science to follow that passion of music.

To compose well, though, you must understand theory, Murray noted. And his other area of interest is in musical theory. In 2013, he published a new theory textbook, “Essential Materials of Music Theory” (Linus Publications), for music majors.

“It’s designed to go beyond fundamentals like how to read and write basic music,” he explained. “In it, there is harmony, melody, form. We talk a lot about musical form and its analysis.”

Training the next Olympians

“People with intellectual disabilities often stick to the same things because they’re familiar; it’s part of their routine. TRAIN helps them to identify sports that they might be good at in Special Olympics, something new to try, based on their skill sets and abilities,” said Natalie Allen, dietetics instructor and dietitian for Missouri State athletics. “I think that’s one of the neatest things about it. It helps people to branch out and tells them you might be really good at bowling, swimming or basketball, why don’t you give that a try?”

At Special Olympics games or recreational events for individuals with intellectual disabilities (like the ones hosted by Arc of the Ozarks), TRAIN is offered to test abilities and introduce healthy eating and hydrating habits. It takes many groups of people to make it successful: exercise and movement science majors and physical education majors run the stations and often complete the physical activity (shuttle run or sit and reach for example) stations with the participant to make sure they understand what is expected; special education students escort and assist the athletes throughout the activities; dietetics students provide information on healthy eating and drinking habits (explaining what food would build muscle or provide energy). Computer science students designed the software that is used, while graphic design students designed the resource materials.

“To get a full profile, we take the data on the form and their assessments from the stations. Then it’s all entered into SNAPPER, the software program, and it prints out their areas of strength,” said Dr. Tamara Arthaud, head of the counseling, leadership and special education department at Missouri State.

“It’s wonderful. Students who have limited touch points with people with intellectual disabilities get to see them in their own culture. They get so see how they live life, and how they interact with friends.” — Dr. Rebecca Woodard

TRAIN is based on an assessment previously designed and administered by the Special Olympics called SHIP, which was very medically driven, according to Arthaud. Missouri State Alum Dave Lennox, vice president for leadership development and education at Special Olympics, Inc., recruited interns from Missouri State who then developed an assessment protocol called FIT, which later was revised into what TRAIN is today.

“This project was picked up by the Finish Line, and they provide all the materials for free,” added Arthaud. “Anyone who wants to do a TRAIN event in their community can contact the Special Olympics, and they will send them a kit with all of the information and all the materials needed. It’s nationwide now because the Finish Line is supporting it, and we are extremely proud that all of these materials were designed by interns from Missouri State.”

A winning experience for all

Everyone agrees the experience is a win-win for the faculty, students and participants. Dr. Rebecca Woodard, professor of kinesiology, requires TRAIN participation in many of her courses as her students need hands-on experience with adapted physical activity. In addition to that experience, though, she sees the interaction as a way of expanding students’ perspectives.

“It’s wonderful. Students who have limited touch points with people with intellectual disabilities get to see them in their own culture. They get so see how they live life, and how they interact with friends,” she said.

Looking beyond the surface to reveal our hidden past

During the pre-Civil War period, Henry McKinley owned about 900 acres of land and held about 15 slaves. Sobel’s field work involved attempting to locate slave quarters at the site.

Growing up, Sobel enjoyed learning about history and the natural environment. “I have always been interested in the human past,” she said. “The field of anthropology, specifically the sub-field of archaeology, brought all my interests together. Archaeologists investigate the human past by studying the material remains of past human activity.”

Sobel, who recently co-authored several chapters in the book, “Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia” and has received several grants for work on the Trail of Tears, has long been excited about working on projects involving indigenous and marginalized social and ethnic groups.

Almost from the start of her career, Sobel was drawn to the study of indigenous Americans. “Some of my earliest experiences in that area occurred when I was in college, when I did an internship with the National Park Service at the Little Big Horn National Monument in Montana, where I got to know some Crow, Cheyenne and Lakota people.” During college, she also interned with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Nevada, in the homeland of Paiute people. These experiences helped her see the benefits of partnerships between archeologists and the descendants of people they study, a practice she has continued with her other projects.

Bringing out a people’s past in ways that haven’t been told completely, or honestly, is one way of bringing about greater equality today, according to Sobel.

“A broader interest I have is trying to help bring to light the heritage of traditionally marginalized social, ethnic and cultural groups – indigenous Americans, African Americans, uneducated immigrants, all of which is a broader movement in recent decades in anthropology, history and other fields. That is an area that is especially appealing to me because it has so much relevance to people today.”

Closer to campus, Sobel, along with graduate and undergraduate students, has been exploring these issues among Greene County pioneers. Part of this project involves the archaeology of two nearby sites – the Nathan Boone homestead in Ash Grove, Missouri, and the McKinley farm in Walnut Grove, Missouri.

The work focused on spatial layout of the sites, the buildings and other structures, as well as graveyards. Sobel’s group, with the assistance of Dr. Kevin Mickus, MSU professor of geology, used ground penetrating radar to reveal underground items, including several graves that were hidden by time. Some of those interred were likely slaves, and buried with them, some of the history of African Americans in southwest Missouri.

“Looking at the trajectories of McKinley family members, as well as of people who were slaves under McKinley, and their descendants gives us insight into race relations and African American heritage in this region.” – Dr. Elizabeth Sobel

Although southwest Missouri did not have large slave populations, there were some slave owners. One of the larger operations in the area was the McKinley farm, where Sobel conducted her 2013 archaeological field school. During the pre-Civil War period, Henry McKinley owned about 900 acres of land and held about 15 slaves. Sobel’s field work involved attempting to locate slave quarters at the site. Because there is not much of a written record from an African American perspective from that era, archeological evidence can yield unique information about slaves’ daily lives.

While she hoped to find evidence of slave quarters at the McKinley site, she and her students were unable to do so. “It was somewhat disappointing, but not unexpected,” Sobel said. “Slavery did not occur on a large scale in southwest Missouri. Sometimes owners and slaves would live together. Or, owners would initially build a small, basic structure for themselves, and later move into a larger house while using the earlier structure as slave housing.” Buildings often had minimal foundations and were made of wood, according to Sobel, and re-used for many purposes thereafter, so little or nothing remains from the original structure as archaeological evidence.

Nonetheless, by combining what written records exist from the antebellum period, along with oral history and artifacts gathered from these and other archaeological sites, researchers can provide a clearer picture about the lives of African Americans as well as Euroamericans during this period.

“Looking at the trajectories of McKinley family members, as well as of people who were slaves under McKinley, and their descendants gives us insight into race relations and African American heritage in this region.”

Couple joins forces to reveal Pixar’s hidden messages

INT. PIXAR FILM

Cast of Characters:

Large, masculine, athletic hero

Various others who admire the hero

On the one hand, the Pixar films are quite progressive and portray men as warm and fatherly, but they often vacillate between this family-man persona and a hyper-masculine male representing a “boys don’t cry” attitude.

“The project started in the car,” said Wooden. “We were on a road trip and listening to “Cars” on the DVD player for the nine hundredth time. We started talking about the way the characters treated each other and the way the film represented winners and losers.”

Having two little boys has given Wooden and Gillam great opportunities to examine the messages in the films, as well as their children’s immediate reactions to it. One example Gillam noted is one of Pixar’s more recent films, “Monsters University,” which shows Mike Wazowski getting bullied for his small stature throughout the film. Eventually, Wazowski learns to accept his role in society rather than fight against predetermined stereotypes.

“What kind of message is that to send to kids?” asked Wooden. “If you have the misfortune to not be born in the right kind of male body, you may as well get used to life as a loser. Try to learn to be happy in your second place — or lower — status, because your options here are find complacency in your ‘lesser than’ status or get really angry, like the lemons did in “Cars 2,” and become punished for an alternative, oppositional form of masculinity.”

Lack of big muscles and broad shoulders isn’t the only thing that Pixar views negatively. Creativity and inventiveness aren’t always a positive trait when it comes to the films, and they are often associated with villainous behavior.

“Take Sid Phillips in “Toy Story” and “Toy Story 3” — he’s a rambunctious, but probably really bright, kid and he’s not doing anything wrong per se,” said Gillam. “He’s taking toys apart and things like that, but the very concept of the movie is that human beings don’t know toys have a kind of life outside being an inanimate object. So in taking heads off and blowing stuff up, Sid is just a kid playing rough.”

EXT. PIXAR FILM

Cast of Characters:

You

Various other movie goers

Wooden and Gillam see numerous opportunities in the films to break these negative stereotypes. Pixar is a powerhouse for establishing social norms, and if applied in a positive manner, these stereotypes could easily be changed or even dismissed entirely, they noted.

“They’ve got incredible influence over establishing, affirming and maintaining cultural norms for kids,” said Wooden. “They’re not the only ones obviously — all society contributes to establishing how kids see the world — but they are a big, powerful, ideological force. Besides, it’s animation. There’s opportunity and potential to rewrite some of these scripts. They don’t have to make Sid the hero of the film, but they could make Sid anything.”

Gillam and Wooden’s first book, “Pixar’s Boy Stories: Masculinity in a Postmodern Age,” was released in April 2014. The book details their research into Pixar’s portrayals of masculinity over the years, and they hope that it calls attention to an often overlooked issue in today’s society.

“Somebody had to be the first person to complain about the Disney princesses’ stifling representation of women, right?” said Wooden. “A parallel conversation for boys hasn’t started, but we’re trying to start it…so people become aware of what they are watching and what their kids are watching.”

Psychology study takes unique look at visual learning

You don’t have to pay conscious attention for minutes to identify each and every vehicle. This is because of past experiences: With repetition of events, such as observing types of automobiles you see frequently, there is an increase in familiarity. As a result, there is a decrease in neural activity regarding these automobiles and your conscious attention is directed elsewhere.

But wait — a DeLoreanwith a flux capacitor has moved next to you. It catches your attention … and in all likelihood, you take longer looks at the DeLorean and your heart rate decreases.

To psychologists, these looks and this change in heart rate are physiological signs that you are having a “response to novelty” and are actively encoding new information. If you saw the DeLorean regularly, it would be what they call a “habitual experience.” Your visual attention to the car would decrease, and changes in your heart rate would not occur.

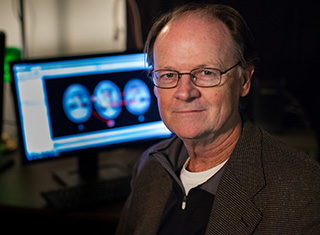

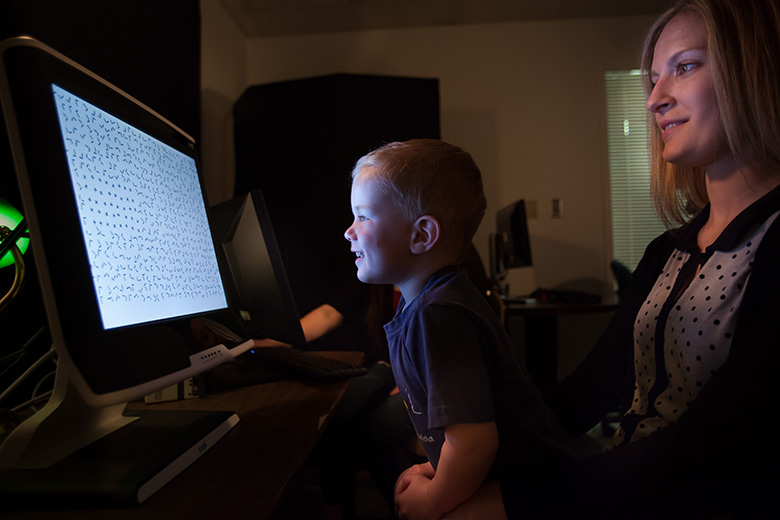

Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State, is in the first phases of a three-year study to examine visual scanning patterns, and associated heart-rate changes, in both infants and adults.

Psychology professor starting a study on visual scanning, changes in heart rate

How quickly a person habituates to experiences is tied to physical and mental development.

Babies who are 2 to 3 months old may look at a new object for as long as eight minutes, learning its visual characteristics. In just a few more months, if they develop normally, they scan the object more exhaustively and quickly.

As an infant pays visual attention to a new object, his or her heart rate tends to decrease. How much it decreases, it is argued, reflects how much information is learned about the new object.

At-risk populations — for example, individuals with mental retardation, attention deficit disorder or schizophrenia, and infants with developmental delays — tend to visually scan new objects differently than normal individuals. The at-risk individuals may continue to take longer looks and may never fully habituate to some experiences. Autistic children, for example, do not look at faces the way others do — they tend to avoid looking at emotion centers such as eyes, noses and mouths, which are the areas of the face most individuals scan first.

Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell, associate professor of psychology at Missouri State, is in the first phases of a three-year study to examine visual scanning patterns, and associated heart-rate changes, in both infants and adults.

He hopes the research leads to new ways to detect developmental problems in infancy or early childhood, then to the creation of new intervention methods to improve visual learning. Hopefully, the findings will prevent developmental delays in at-risk infants and young children.

Eye-tracking technology leads to exceptional amounts of data

Mitchell and his students place research participants in front of an apparatus called a Tobii eye tracker. Tobii looks like a regular computer monitor, but it’s really collecting a gold mine of visual data. The participant is also attached to electrodes via a separate computer and laboratory system. These record and monitor heart rate.

Next, the participant is shown a series of black-and-white images on the Tobii screen.

“We try to develop stimuli that are something you’ve never seen before,” Mitchell said. He and his students design abstract shapes, make line drawings of animals and modify photos of faces.

“The more we can understand developmental and individual differences in visual learning and scanning, the better we can develop appropriate interventions to help those infants and young children with learning deficits.” — Dr. D. Wayne Mitchell

Tobii’s software compiles information about where the participant has looked, how many times they looked there, how long they looked and how rapidly they responded to different areas of the image. Researchers can then compare visual patterns created by those with and without developmental delays or disabilities.

“This gives us more data than we could even hope to get elsewhere,” said Bret Eschman, an experimental psychology graduate student. “It gathers so much information so quickly.”

This data is unique to Missouri State: Although the Tobii is increasing in popularity among researchers, it appears few are using it to study early visual development. Mitchell said he doesn’t know of any other infant researchers who are investigating both visual scanning and changes in heart-rate data at the same time.

Mitchell’s study started in January. He hopes to test at least 200 to 300 participants, ranging from ages 4 months to adult.

“The more we can understand developmental and individual differences in visual learning and scanning,” he said, “the better we can develop appropriate interventions to help those infants and young children with learning deficits.”

Ancient Greece leaves legacy of drama, democracy and argument

“The Athenians had quite a list of statutes written down on everything from business deals to prosecuting a killer. The really interesting thing is these rules sort of shaped the rules of rhetoric or the art of argument – the way you persuade people to take your side in a case,” Carawan said.

While the inscribed laws list the do’s and don’ts of Greek society, Carawan focuses more closely on the speeches delivered in those days. While it is now standard practice for most politicians to have a speech writer on staff, speech writing for profit was something the Athenians created.

Dr. Carawan noted that the ancient Athenians created the art of speech writing and rhetoric, both of which have inspired his publishing projects.

Based on these speeches, Carawan derives what the layperson presumed about the laws and how statutes were interpreted, giving Carawan a deeper understanding of the culture. This cultural understanding is what motivates him to each new research project, recognizing the differences in lifestyles 2,500 years ago and the metamorphosis of ideas and beliefs over time.

“I find I use this obsession of mine all the time,” he said. “When reading Plato’s “Apology” with students, these concerns come very prominently into discussion. Looking at the trial of Socrates and the charges against him, we discuss popular thinking on issues like freedom of speech and freedom of conscience.”

Civilization gives him plenty of ground to cover

Carawan’s most recent book, “The Athenian Amnesty and Reconstructing the Law” (2013), addresses how the law system was rebuilt after a divisive civil war between the 400 and 300 B.C. After that war, people had to not only reestablish statutes, but they also had to decide which punishments and obligations carried over from one regime to the next. His first book, “Rhetoric and the Law of Draco” (1998), focuses on homicide law.

Research for his next book has already begun in which he will investigate constitutionalism at Athens, particularly looking at the question of the sovereign governing body being accountable to a higher power. From his early research of the 400 B.C. period, he has noted the only higher authority seems to be the best interest of the people.

“The really interesting thing is these rules sort of shaped the rules of rhetoric or the art of argument – the way you persuade people to take your side in a case.” — Dr. Edwin Carawan

“What interests me is that in the mid-300s B.C., there are a number of important speeches that seem to be reaching for something that most people haven’t got yet – a kind of contractual idea. That people, when they make decisions, form certain obligations,” said Carawan. “The idea that a higher authority could arbitrarily change any of those commitments is puzzling and problematic to many of the speech writers.”

Sharing his passion with students, scholars

It was during his own college years that Carawan became fascinated with political theory and ancient literature, and his passion for and curiosity on the subject is endless. Part of this interest stems from the inherent uncertainty when looking at historical texts and accounts of the same event.

“There’s always something that bothers me in the body of inherited opinion – something that has become what I like to call the canned goods just doesn’t smell right. So you go back and look at the evidence again and see what the other approaches might lead you to,” he said.

He hopes to share this passion with many more students, and one way is through a study abroad program to Greece that was recently established.

“Fitting” in at work

Dr. Wes Scroggins, associate professor of management at Missouri State University, has been researching different ways for employers to approach both hiring new employees and managing overall employee performance.

“One of the big focuses of my research has been the area of person-job and person-organization fit,” said Scroggins. “Person-job fit means fitting a person to a specific job, while person-organization fit is how people fit or match the organization in which they’re employed.”

When companies and business look to hire new employees, they focus on one fit: ability. What if they focused on other types of fit, such as the extent to which the job supplies what the individual values or desires? This is the question that Scroggins focuses on, and he hopes that by bringing it to the forefront of the minds of hiring managers they will begin to practice more effective hiring techniques.

“At least in theory, if there is a good demand-ability fit, then the person ought to be a good job performer,” said Scroggins. “The problem is, though, that often times things such as job attitudes or motivation also indirectly influence performance behaviors and might influence other important behaviors, such as turnover behaviors.”

Focusing on fits other than demand-ability can lead to higher retention rates, increased productivity and better overall satisfaction for employees. In other words, employees shouldn’t just be good at their jobs — they should enjoy their job and feel as if they belong in the organization as a whole to be truly successful in their position and career.

“In my doctoral dissertation, I proposed a different, third form of person-job fit that I simply called ‘self-concept job fit,’ and I defined that as the extent to which the nature of the work that the person performs in their job really affirms their sense of self, their self-concept,” said Scroggins. “You hear people sometimes say ‘This job is just me. I love it.’ I basically proposed that form of fit would be the form of fit that would most likely produce meaningful, purposeful work in a person.”

This focus on person-job and person-organization fit isn’t just relevant for managers here in the United States. Companies across the world could benefit from these perceptions, and Scroggins hopes to extend his research internationally.

“The question is, across cultures, given cultural differences, do people in other cultures have the same perceptions? Is their perceptual structure, of fit with the job or organization, the same as the folks here in the United States?” said Scroggins.

“I’ve collected a little bit of data from some Dutch workers in the Netherlands. I hypothesized that I would find some significant differences between the perceptual structure of my American samples and the Dutch sample, but surprisingly what my initial results are indicating is that there is a lot of similarity between how people across these two countries perceive fit within a job and organization.”

Flying south to study the heat in a very cold spot

“This is one of maybe three or four volcanoes in the whole world that when you go up to the crater you can see lava. This one you get to the top and you look down, and yep, there’s a lava lake down there – you can see it bubbling,” Mickus said. “Recently, the floor of the crater has risen 90 feet and there has been stuff shooting out of the volcano.”

Mickus’ primary focus in Antarctica is conducting gravity readings to determine any changes in the magma levels and confirm the seismic results.

Mount Erebus is classified as active due to its frequent Strombolian eruptions – an eruption of light, magma and rocks that happens after bubbles are formed due to a buildup of gas – but it has infrequent ash eruptions and historically rare lava flows. Actually, the lava flow for decades has been confined to the inner crater. Mickus noted that it’s thrilling work, but he hasn’t really been concerned about a destructive eruption.

That all may change, though. The volcano hasn’t erupted since 2011, but it’s near two scientific research bases (McMurdo Station and Scott Base), so it is monitored regularly for safety precautions. Another research team conducted seismic research of Mount Erebus a few years ago and found some regions that indicated it was hot. So Dr. Phil Kyle, a scientist from New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology who has studied in the region for approximately 40 years, invited Mickus to join the team in 2012.

Using a gravity meter on loan from the Department of Defense, Mickus’ primary focus in Antarctica is conducting gravity readings on Mount Erebus to determine any changes in the magma levels and confirm the seismic results.

“We want to understand more about the whole volcanic system,” said Mickus. “We’re looking to understand the sub-surface type things and trying to understand the magma system underneath… Different rocks have different densities, and we can determine that to get an idea what’s underneath the surface.”

Approximately six miles deep inside the crater lays a mass of magma, noted Mickus. With the gravity meter, he hopes to determine the movement pattern of that magma or definitively say whether there is heat conducting near the surface. This heat source has caused a unique and dangerous geological feature to form – ice caves.

Mickus researched in Antarctica again in November and December of 2013, and currently is writing proposals to continue his studies with the hope of taking a student research assistant on a future trip.

Hydrogen drives the future of energy

“How do we harvest and store energy so that it’s done in a benign manner to the environment?” Mayanovic asked. “One of the things we’re aiming to do is to make energy conversion more efficient. One way to do that is to go with higher temperatures and pressures for the exchange and mediating fluids in energy-conversion reactors.”

Although hydrogen is the simplest element – only one proton and one electron – it occurs naturally only in minimal amount as a gas on Earth. It is only found in compounds with other elements, as in water combined with oxygen, or in many other fuels like gasoline, natural gas, methanol and propane. Obviously, burning fossil fuels like coal or extracting hydrogen from gasoline impacts the environment negatively, so Mayanovic is collaborating with other scientists within the EFree center, which is part of the Energy Frontier Research Center program, to find a more sustainable solution.

In physicist Dr. Robert Mayanovic’s laboratory, he and his students are researching materials to extract hydrogen more efficiently to make it a readily available energy source.

Small doesn’t begin to describe it

Since his days as a student, Mayanovic has been drawn to research of materials in extreme environments, like high pressure or in fluids at high temperature and pressure. He’s also focused his research on nanoscale materials, something so small that thousands could fit within a hair and is invisible using an ordinary optical microscope. Instead, to work with nanoscale materials, he uses a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

In his lab, they have been able to modify some of the nanoscale materials to make them more responsive in the visible range (opposed to the ultraviolet range) for applications involving splitting water to harvest hydogen. However, he isn’t satisfied with the efficiency of these materials as they are still impractical for widespread energy applications. Similarly, he noted electrolysis (the process by which you split water to make electricity) is an inefficient method because you spend more energy than what is extracted in the form of hydrogen.

“What you want to do is use the sun within a cell that is able to split water and make hydrogen sources that you can tap as you need,” said Mayanovic.

“We hope to cause a reaction to convert the biomass into hydrogen or methane, so you have a new energy source.” — Dr. Robert Mayanovic

Extreme laboratory

Behind the safety goggles, you also will see work being done in Mayanovic’s lab on materials with catalytic or reactive properties to induce biomass gasification.

“What you’re doing is taking your biomass, putting it in a reactor under high pressures and temperatures with water,” he said. “We hope to cause a reaction to convert the biomass into hydrogen or methane, so you have a new energy source.”

These extreme environments – the high pressures and high temperature fluids – make the study very unique from others who are looking at harvesting hydrogen. Because of his unique perspective, he incorporates the research into even his most basic physics curricula, to demonstrate the application of physics to world issues.

When students visit his laboratory for class, one instrument in particular usually draws his students’ attention: the high pressure cell.

“It uses diamonds to create pressure,” Mayanovic explained. “You put a gasket in between two gemstones, like diamonds, to create a great deal of pressure and it allows you to study materials under extreme environments.”

Seeking treatment for brain’s ‘perfect storm’

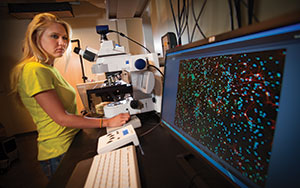

Brittany Thurman, a biology major, uses a fluorescent microscopy to study how new drugs being developed to treat neurological diseases control cellular activity.

A perfect storm: It can erupt at any time if a variety of factors interact just right. Maybe it all starts with a stressful day at work. Although you’re relieved to go home and get work off your mind, you can’t, leaving you with a fitful night of sleep. When you wake, you have a kink in your neck. The morning rolls on, and you juggle your schedule as well as the needs of your household. You step onto an elevator — part of your normal routine — and you take a whiff of strong perfume. Your sinuses are stimulated, and you undergo a migraine attack.

In the world of Dr. Paul Durham, professor of cell biology at Missouri State University and director of the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, that is the “perfect storm” model. In this model, each factor plays a role in making the nerves more hyperactive and sensitive, until one of them tips the balance.

“These nerves begin to do their job a little too well,” Durham said. “Instead of responding to a stimulus in a normal way and alerting you about it, the nervous system response becomes not physiological, but pathological.”

In the early 1990s, during his postdoctoral work at the University of Iowa, Durham became interested in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) — a protein made in nerve cells and known to promote inflammation. As a cell biologist, he was intrigued that increased CGRP levels were correlated with the pain intensity of a migraine attack. Twenty years later, he is an international expert on the study of the trigeminal nerve and orofacial pain.

The trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the head and face, so Durham studies the biological basis for migraines, headaches, temporomandibular joint (or TMJ) pain, jaw pain, toothaches, gum pain, sinus headaches and rhinosinusitis, among others.

His work could have tremendous impact, as studies have shown that approximately 36 million Americans suffer from migraines.

Studying causes of pain, ways to treat it

Graduate chemistry student Geoffrey Manani uses techniques called high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and gas

chromatography mass spectrometry to identify compounds in plant and animal material that suppress inflammation and promote healthy cell activity.

In his lab at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, known as JVIC, Durham researches why nerve cells become hyperactive and why they cause pain. Nerve cells are grown in culture dishes, allowing him and his fellow researchers to see how cells react with various drugs.

During the past couple of years, his research team took their quest for answers one step further: How and why does pain move from acute pain to chronic pain?

“What we’re finding with chronic pain patients is they get themselves in a vicious cycle,” Durham said. “Once they start having pain, they usually don’t sleep as well, which usually causes them more pain. Then they begin to stress about it, and then they get depressed about that. All of these things keep snowballing. Pretty soon you have a system that is out of balance.”

Partially due to his involvement with organizations such as the Society for Neuroscience, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Headache Society, Inflammation Research Association, American Academy of Orofacial Pain and the American Pain Society, pharmaceutical companies often enlist his help in determining the viability and effectiveness of their products. Since JVIC opened in 2007, Durham has been awarded more than $9 million in grants, including funding from pharmaceutical companies and government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health.

“The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results.” — Evan Clark, student

Students of all ages can assist in research

Durham’s laboratory is involved in the identification and characterization of bacteria obtained from medical tissues as well as food products.

As you tour the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences, or CBLS, at the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, you may notice how young everyone appears. The approximately 20 researchers in the lab are a mix of full-time employees, undergraduate and graduate students — all homegrown from Missouri State University, Durham noted. Durham holds the only PhD degree in the lab.

“I’ve never looked at undergrads as being any different than grad students,” he said. “If someone is passionate about science and learning, and we put them in the right environment, then they just take off.”

Evan Clark, a senior who has worked in Durham’s lab since 2011, said the CBLS lab has taught him about the design and set-up of medical clinical trials, the importance of teamwork and organization, and the procedures and protocols of research.

Junior biology major Andrew Miller prepares samples for bacterial analysis.

Clark led a menstrual-related migraine study: “The experience was completely hands-on. I worked directly with the samples, organized a majority of the data, conducted the experiments, organized personnel to finish the study and finalized results,” Clark said. “I am truly appreciative of the opportunity Dr. Durham has given me. His support has made me a better student and person.”

In the last 10 years, Durham has supervised the research of more than 75 students in the CBLS, and says this is one of the best parts of his job: “The students have played a key role in everything we’ve been able to do.”

In the lab, at home, in the classroom or in his downtime, Durham lives to help people — especially youth. As an example, one of his current studies may help eliminate children’s fears of needles.

Instead of using blood as a diagnostic indicator, Durham has studied the effectiveness of using human saliva to look for protein levels, discern what each protein indicates and understand the progression of diseases. Now he’s researching the saliva of a group of neonatal babies and pediatric oncology patients in Utah, planning to develop a diagnostic tool to measure biomarkers in saliva that hospitals and doctors could use instead of drawing blood from children.

JVIC: great resources, collaborations

Jordan Valley Innovation Center, a former milling facility, is a seven-story state-of-the-art research and innovation accelerator. When it opened in 2007, it became the home of CBLS, staying true to its commitment to the development and support of advanced biotechnology industries in Missouri.

Human cancer cells, which can be stored for years in liquid nitrogen, are often used in Durham’s research since they mimic normal human cells.

JVIC is also home to corporate affiliates in the medical, technology and defense industries and the Center for Applied Science and Engineering of Missouri State.

“We have the full complement of all the techniques and equipment that we need in one building, which is really unique,” Durham said. “Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.”

In addition to equipment, Durham said the ability to collaborate with scientists with other expertise has been a huge advantage of being housed at JVIC. One prime example was the development of a “smart” bandage that delivers a drug to promote healthy wound healing.

Starting with a tent material that would decontaminate biological and chemical warfare agents — a product that was developed at JVIC as well — Durham and others at JVIC collaborated through several stages of development. And it was a success.

“It took electroactive polymer chemists to figure out how to put the matrix together, but then you had to have material science people working on how to make a bandage that didn’t stick to the wound. Then you needed electrical current going to the bandage, so you had to have someone who could build an electric device that delivered the right amount of current,” he said. “With the help of Crosslink, an affiliate of JVIC, we were actually able to work with their scientists to develop the product and have it release the drugs that we wanted into the wound to promote healing. We all worked together as a team to make it happen.”

“Most people who visit are blown away by all of the resources that we have at JVIC.” — Dr. Paul Durham

Empowering people to prevent disease

The worldwide scientific community collaborated to complete the Human Genome Project in 2003, sequencing the chemical base pairs of DNA to determine the significance of each gene. Since then, research has shown that the average person has 10 genes predisposing him or her to a major disease. Keeping that illness from becoming a reality is another area of research interest for Durham.

Joshua Haydon, junior research scientist, prepares cancer cells to study the effect of a nutraceutical product on inflammatory pathways known to promote disease progression.

“Why are they still healthy? What it comes down to is diet, exercise, good environment and healthy sleep patterns,” he said.

On top of the DNA structure (the genome) is another similar structure called the epigenome, Durham explained. The epigenome, which is responsible for how DNA is packaged and controlling what genes are turned on or off in a cell, can be manipulated through diet, exercise and sleep.

“For example, if you have a ‘bad’ gene that increases the likelihood for a disease, you could completely turn it off for most of your lifetime through epigenetic changes.”

It’s a powerful thing — empowering patients with the knowledge that they have control over a disease. Durham sees nutraceuticals, compounds found naturally in fruits, vegetables and plants, as an emerging field in the next 10 years. These nutraceuticals will be key in a lifestyle plan to keep the epigenome from manifesting certain illnesses.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

One nutraceutical Durham has studied extensively is the cocoa bean, which is used to make chocolate and was praised by early civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas due to its medicinal properties.

“Five or six years ago, we started looking at cocoa and wondered what would happen if you incorporated more dark chocolate in your diet. Would that actually protect you against certain pain pathways? When you incorporate dark chocolate into your diet, you are basically quieting pain-conducting nerve cells. The cocoa modulates a healthy response toward inflammatory and painful events. So the cocoa actually blunts the perfect storm that’s developing.”

Migraine sufferers take heart — clearer days are ahead. Durham and his team of researchers are working to find relief for this debilitating affliction.

Student examines effect of new pesticide on mussels

“Dr. Barnhart can be considered the godfather of mussel-rearing,” Pletta said.

Pletta worked for a year and a half in Minnesota on a field-survey team studying mussels in the Mississippi River, then graduate school beckoned. The opportunity to work with someone like Barnhart drew her to Missouri State.

Students see full life cycle of mussels

Dr. Chris Barnhart, biology professor, and Madeline Pletta examine mussel shells from the Meramec River, which has roughly 40 native species of freshwater mussels.

The Missouri State lab is a captive-propagation facility, which means mussels live there and are bred in a controlled environment.

Pletta gained hands-on lab experience and led research projects on a variety of mussels, including the federally endangered pink mucket and invasive species such as the zebra mussel.

Freshwater mussels start life as larvae: tiny, temporary parasites that live on the gills of fish. These are captured in the lab on fine screens after they drop off the fish. Several hundred nearly microscopic juvenile mussels can be obtained per fish.

These juveniles grow to the size of several centimeters in the MSU facility. Barnhart also has a mussel-culture facility at the Kansas City Zoo, and the animals grow to a larger size there. These mussels are used for toxicology research, as well as restoration of endangered species.

“Mussels from the size of a pinhead to the size of your fist are raised at Missouri State and at the Kansas City Zoo,” Pletta said.

Student’s thesis may help native mussels

Barnhart’s lab was approached by Marrone Bio Innovations, a green pesticide company, to test the effect of its new molluscicide (a pesticide that kills mollusks) on native mussels. The molluscicide, Zequanox, is used to control the zebra mussel, a non-native species that is a pest in many parts of the world. This project became part of Pletta’s thesis research, so she could ensure Zequanox does not harm native mussel species.

Mussels benefit the ecosystem because they filter water as they feed. However, the invasive zebra mussel is hazardous since it can adhere to anything. One example Pletta noted was the ability of zebra mussels to clog pipes carrying cooling water in power plants.

Madeline Pletta and Dr. Chris Barnhart look at largemouth bass kept in tanks in MSU’s Temple Hall. Barnhart and his students inoculate these fish with mussel larvae, since mussels initially develop as parasites on fish gills. The larvae eventually fall off and are raised at Missouri State and the Kansas City Zoo.

The first stage of her research involved testing toxicity of Zequanox on four species of native mussels, including the endangered pink mucket. The tests showed Zequanox has very little effect on the native species, indicating it is a promising product. Then she expanded her research to include seven species, researching their ability to capture different sizes of food particles.

Using a highly sensitive particle counter, Pletta released polystyrene microbeads along with food into tanks of mollusks and tested the water at specific increments. As she watched, waited and tested, she found some surprising results.

“The overwhelming knowledge and literature out there says zebra mussels are excellent at clearing small particles and that native mussels aren’t. Realistically, what I’ve seen is that natives are as efficient, or more efficient, than zebra mussels at capturing the smallest particles when you’re taking the body size into account.”

Ultimately, her findings will be instrumental in determining the appropriate particle size and concentration for Zequanox, as well as allowing Marrone Bio Innovations to get Environmental Protection Agency approval for open-water use of their product.

Did you hear? Students offer free screenings

Dr. Wafaa Kaf, a professor of audiology from Al Sharqia, Egypt, has spent many of her 10 years at Missouri State researching ways to evaluate the hearing of these challenging populations.

Kaf is most interested in detecting mild degrees of hearing loss using “electrophysiological measures” — ways to assess hearing that don’t rely on patient response, but instead objectively track the brain’s responses to sounds. She may use electrodes placed on a patient’s head or probes inserted into a patient’s ear.

Why hearing screenings matter

Luke Wilson, 3, is given a hearing screening by Dr. Wafaa Kaf. The electrodes measure his brain’s responses to sounds.

Kaf said hearing loss is a substantial problem that is largely hidden, and estimates that there are 35 million American children and adults with mild, moderate or severe hearing loss. They may experience no symptoms, or just have slight ear pain or an ear infection that resolves quickly.

However, hearing damage lasts forever.

“Hearing is one of the most important things for children because it is the precursor for them to develop the ability to talk,” Kaf said. Hearing loss may lead to stunted speech-language development, making these children feel less competent and confident when they reach school.

These students may be held back academically and socially due to a problem they cannot control and may not even know about.

Addressing the community problem

Kaf started a service-learning pediatric audiology class for doctoral students in 2005. With her supervision, students perform free hearing and middle-ear screenings for low-income and underserved populations. Since the start of the class, she and her students have screened more than 400 children in the Ozarks.

The audiology students take portable equipment to community partner organizations. There, they screen their subjects — who are typically 6 months to 5 years old — with the consent of the children’s parents or guardians.

Afterward, Kaf supervises her students as they write a report to parents. If hearing problems or an ear infection were detected, they recommend a rescreen, a visit to a pediatrician or a complete audiologic evaluation.

Kaf’s dedication to serving others doesn’t stop there. She often tells parents to bring their child to her lab at the Missouri State Speech, Language and Hearing Clinic. This clinic has the extensive, nonmobile equipment needed for a full evaluation. She either supervises a graduate student or does the evaluation herself.

All of this is provided at no cost to the parent. Kaf guesses this service-learning class has saved parents in the community thousands of dollars.

“It’s an intensive workload, but I feel I am their advocate. These are parents who are in the most need of that service for their children.”

Dr. Wafaa Kaf works in the audiology lab. Kaf has spent many of her 10 years at Missouri State researching ways to evaluate the hearing of challenging populations.

Advancing the audiology profession

Kaf and her students are assisting not just the community — they are helping audiology experts.

Since every child is different, audiologists need many tactics to ensure accurate screenings. Kaf and her students investigate innovative, objective ways to detect mild degrees of hearing loss and methods to weed out unreliable responses.

She and her colleagues have published their research in national and international journals for audiology professionals.

Her next study takes place in U.S., Egypt

This instrument offers an objective, painless way to measure otoacoustic emissions, echoes from within the inner ear.

Kaf is taking a sabbatical in fall 2013 for a pilot study on detecting mild hearing loss in young children. She started the study in the Ozarks and will continue it in Egypt, her home country.

“With our traditional measures, mild hearing loss is often missed. We detect it later, when the child starts to behave like he cannot hear everything or when he does not quite have age-appropriate speech and language development — but this is too late,” she said.

“I want to advance the testing protocol for newborn hearing screenings so we can detect mild hearing loss as early as possible.”

Scholar explores one of world’s oldest Buddhist Cultures

But it is. And that’s one of the things that attracted Buddhist studies scholar Dr. Stephen Berkwitz to Sri Lanka in the first place.

Although Berkwitz, professor of religious studies and current department head, originally hails from Minnesota, he has long harbored an interest in Asia.

“I became interested in studying Buddhism, particularly Buddhism in Sri Lanka, which has a very long history,” he said.

“I chose Sri Lanka as a location for my research because it continues to house a living Buddhist culture and the language that is spoken there is more closely related to the ancient Indian languages I was studying in graduate school.”

Buddhist tradition

This reclining Buddha is at a temple in Sri Lanka. It had been neglected and even damaged before steps were taken in recent years to renovate the archaeological site. Photo by Stephen Berkwitz.

Instead of focusing on the arguably more familiar Zen or Tibetan traditions, Berkwitz was drawn to Theravada Buddhism. “I was and remain interested in Theravada Buddhism, which does have a very long history and a more conservative orientation,” he said. “That combination I find intriguing – that commitment to preserving an ideal against pressures to change. Sri Lanka is particularly dedicated toward that preservation ethos. Its close connection to India also gives it a distinctive development compared to other forms of Buddhism.”

Unlike many Buddhist studies scholars, however, Berkwitz has chosen to focus on literary efforts beyond the canonical. “My research has been focused on Sri Lankan Buddhist history and literature primarily,” he said. “One thing that probably characterizes my work and interests is to go outside of a strictly monastic setting and look at how the Buddhist religion was expressed and practiced in the wider society.”

Recent research

An example is his recently published book, “Buddhist Poetry and Colonialism: Alagiyavanna and the Portuguese in Sri Lanka,” which explores the tumultuous change one poet experienced as Sri Lanka was colonized by the Portuguese. The verses of poetry translated in the book provide a window into the tremendous religious and cultural transformations of the early 17th century, when Europeans and Asian Buddhists sustained and intensified exchanges.

Berkwitz began the research for this book in 2005, attained a Fulbright scholarship to continue the research, learned to read Sinhala poetry and the Portuguese languages and spent seven months in Sri Lanka.

This is Somawathiya Chaitya, a “stupa” (domed Buddhist structure). It is located within Somawathiya National Park. Tradition holds that it was built in the second century BCE to enshrine a relic of the tooth of the Buddha. Photo by Stephen Berkwitz.

He also received a Visiting Research Fellowship to Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany in 2011-12. During that time, he made several research trips to Portugal to study the colonizer’s views of Buddhism.

During his fellowship in Germany, Berkwitz further explored the Portuguese encounter with Buddhism in Asia. “There is a large German government-funded project, ‘Dynamics on the History of Religion between Asia and Europe,’” he said. “I was among about a dozen international Fellows invited to do research, with my focus being the encounter between the Portuguese and Asian Buddhist in the 16th and 17th centuries.”

Indeed, there are only a handful of scholars in the world who focus on the areas Berkwitz studies, but that doesn’t diminish the growing importance of his work.

“It’s a small number, but it’s timely because there is a great deal of interest in the humanities in general to look at the history of cultural encounters,” Berkwitz said. “By looking at these encounters, scholars are seeing potential for understanding the role these exchanges had for shaping the development of people and places in the modern world.”