Associate professor of history Dr. Sarah Mellors has been studying modern China for 20 years, ever since she started intensive Mandarin lessons as a freshman in college.

Mellors, who has been with Missouri State for six years, currently teaches courses on premodern and modern East Asia (China, Japan and Korea), 20th century China, gender and sexuality, and the history of medicine.

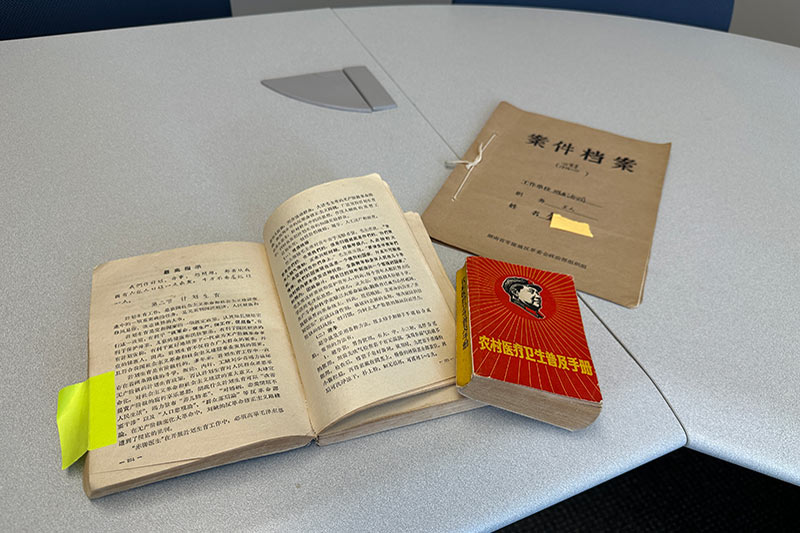

Her most recent book, “Reproductive Realities in Modern China: Birth Control and Abortion, 1911-2021” (Cambridge University Press, 2023), blends those specialty areas into a focused examination of reproductive health history in 20th century China.

Mellors has given numerous talks on China’s reproductive health history, including at events hosted by Harvard University, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Rush University Medical Center, the University of New South Wales, the University of San Francisco, the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, the University of Exeter and the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Although audiences at these sessions ask a variety of questions, Mellors frequently finds herself fielding questions about China’s population future.

“Audience members at these talks want to know what China’s fertility policies will look like in the future, now that the population is graying and the government is pushing for three-child families,” Mellors said.

“[They] also are very interested in how ethnic minorities fared under the One Child Policy.”

Intrigued by contradictions surrounding China’s One Child Policy

Mellors first became interested in China’s reproductive health history while teaching in China, where she encountered surprising contradictions between what China’s One Child Policy was designed to do versus how that policy was actually carried out.

“I had heard that the One Child Policy was in effect,” Mellors explained, “but the students in my classes kept telling me, ‘Oh, I have so many siblings. This is commonplace where we live.’”

The contradictions intrigued Mellors. And her curiosity grew as she learned more about China’s reproductive health history.

For example, while Mellors was teaching history to students and faculty at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, she learned more about China’s One Child Policy from her colleagues.

“When I became closer with the faculty members, they confided in me that they had had multiple abortions under the One Child Policy,” Mellors said. “If they had refused to undergo abortions, they would have lost their jobs.”

This got Mellors interested in questions about China’s “regional variations in policy implementation.”

To explore those questions, Mellors entered the University of California-Irvine as a graduate student and started formally researching the history of China’s reproductive health in 2014.

“I considered researching the One Child Policy, but I wanted to do so from a historical perspective,” Mellors said. “I wanted to move away from this top-down, policy-focused analysis of what I see as a very human thing: reproduction.”

“That’s what got me interested in trying to see what came before the One Child Policy, and what that looked like at the individual or grassroots level,” she added.

Mellors encountered several surprising facts during her research.

“I was surprised to learn that although family planning was mandatory under the One Child Policy [enacted] from 1979-2015, approximately two decades earlier the government severely limited access to birth control and abortion in an effort to promote rapid population growth,” Mellors explained.

“In other words, had the government not forced couples to have large numbers of children in the 1950s, China likely would have had a smaller population,” she added. “There would have been no reason to enact the One Child Policy, although many scholars have argued that the policy was never necessary.”

Rhetorical approaches to policies key part of history

Mellors was also struck by the different rhetorical approaches behind reproductive health policies in China compared to those in the United States.

“Not only do the U.S. and China have different timelines in terms of advances in reproductive rights, but the conversations around reproduction have differed significantly in each country,” Mellors explained.

“The U.S. conversation about reproduction is an individualist one: it’s about oneself and one’s personal rights. The ‘my body, my choice’ slogan conveys that,” Mellors said. “Whereas, in China, the ‘my body, my choice’ slogan is not what you hear the most. Instead, it’s mostly, ‘your body, China’s choice.’”

“It’s a very nationalistic framing.”

Mellors notes that China’s discussion of it reproductive health policies continually fluctuates.

“The conversation is shifting since the rollback of the One Child Policy and the emergence of more recent feminist protests,” she added, “but I still think the individualist focus isn’t there in the same way as it is in the U.S.”

“Mostly, the discourse stresses how reproduction is yoked to the nation, eugenics, ethnic politics, economic development, etc., but not to individual women’s wants and needs.”

Invaluable lessons from exploring China’s history

Mellors sees tremendous benefits in learning more about modern Chinese history, as it aligns with Missouri State’s public affairs mission.

“Studying modern Chinese history is essential for understanding how China became a leading global economic power and why the Chinese government has made the choices it has,” she explained. “Without that context, it can be difficult to interpret China’s domestic and foreign policies.”

“I wish that people understood that China is a vast and extremely diverse country,” Mellors added. “No one person’s experiences are representative of the whole country. This also pertains to how people experienced the One Child Policy.”