Native Americans contributed a military tactic crucial to saving lives among U.S. troops in both world wars: use of their Native languages.

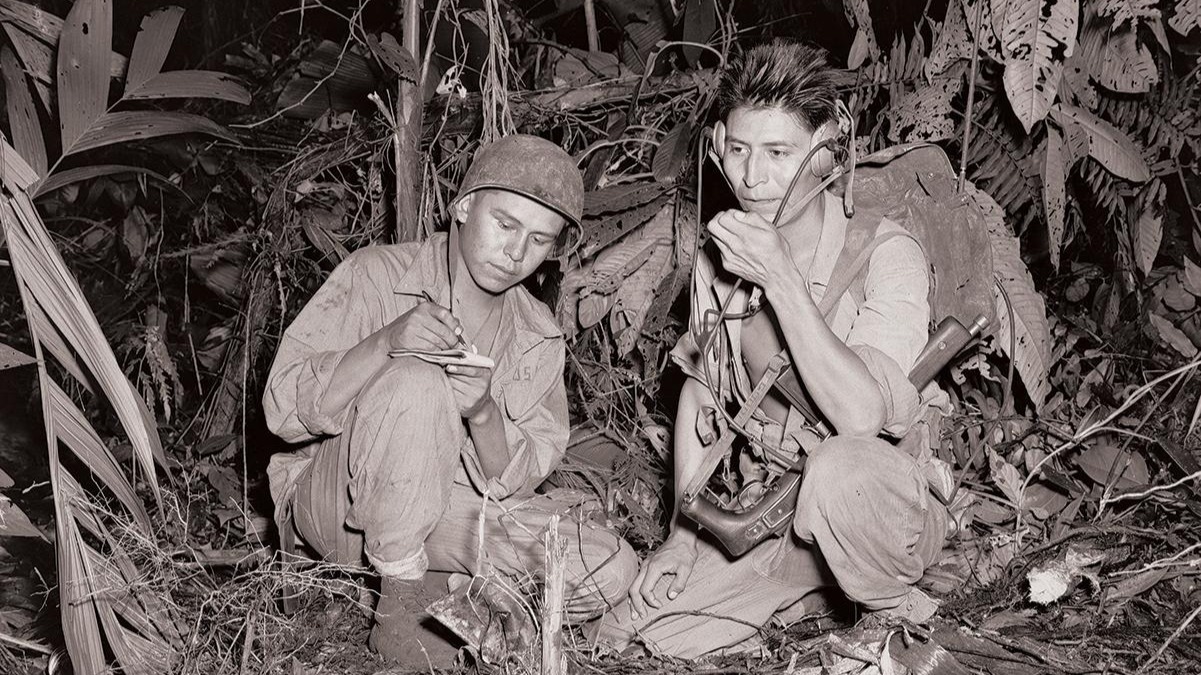

The direct Native languages and coded vocabulary based on them – named code talking – secured the U.S. military’s communications. The tactic ensured that even if enemy armies intercepted U.S. military messages, they couldn’t decipher them.

Dr. William Meadows, professor of anthropology and Native American studies at Missouri State University, leads efforts to uncover the full extent of code talkers’ legacy.

He recently published an article in American Indian Magazine on the subject, as well as a book on the first code talkers of World War I.

Who were the code talkers?

Members of more than 30 Native American tribes served as code talkers in the U.S. military, including the well-known Navajo.

They developed coded words and systems as translation tactics for brief U.S. military communications.

“Code talkers avoided repetition in their communications, making breaking the military codes much harder,” Meadows said. “As brief messages, they also allowed for quicker relays of information and response times.”

Spreading recognition of their military contributions

Code talking helped shape successful U.S. military strategies. But code talkers received little attention for their military contributions before Meadows’ work.

“There were only a few paragraphs of written material on the subject when I started,” he said. “Exploring their contributions was something that needed to be done.”

Meadows’ research began decades after most code talkers had died. Yet his work has helped their legacy live on.

He testified in a Senate Committee hearing to help start legislation that led Congress to pass the 2008 Native American Code Talkers Act.

The well-earned recognition is something code talkers never sought themselves, Meadows shares.

“Code talkers in both world wars attended boarding schools that strived to suppress their Native languages and cultures to assimilate them as Americans,” Meadows said. “Making obvious contributions to the military through their Native ways as code talkers not only offered a great twist of irony. It also filled each with a great sense of pride to know their cultures played a central role.”

Combating stereotypes

Native Americans battled an extra force in both world wars: the stereotype deemed Indian Scout Syndrome.

“The syndrome relates to a belief that Native Americans have biologically inherent abilities that make them naturally better at military tasks than anybody else,” Meadows said.

These skills included heightened hearing, better night vision and a natural sense of direction.

The belief led military commanders to assign Native Americans dangerous positions as scouts, snipers or point men.

Some Native Americans volunteered for the positions because they felt they could fulfill the role well. Others strived to meet the expectations of their non-Native American comrades.

This led to a higher wounding and death rate among Native American soldiers.

Meadows notes that hunting, trapping and fishing hone these skills in many people raised in rural areas – not just Native Americans.

“Native Americans continue to compose a larger percentage of any ethnic group in the U.S. Armed Forces,” Meadows said. “This makes understanding the causes of Indian Scout Syndrome and how to overcome it relevant to military success even today.”

Preserving history by connecting generations

Recording the history of code talkers takes more than research. It also involves speaking with elders who lived as code talkers themselves or had connections to them, Meadows shares.

These interviews reveal Native Americans’ military experiences for historians, as well as for Native American families and their tribes.

Lanny Asepermy, a Vietnam veteran and retired master sergeant of the U.S. Army, is a member of the Comanche tribe. He has seen the influence of Meadows’ work firsthand.

“Dr. Meadows has provided both the Indian and non-Indian worlds with a small piece of written history that was only known through oral stories,” Asepermy said.

Connecting with elders allows Meadows to bring their stories to younger generations of Native Americans, including code talkers’ descendants.

“One of the best experiences I’ve ever had was when a boy told me he had stumbled upon one of my books at the library. He found I had interviewed his great grandpa,” Meadows said. “The boy told me I couldn’t know how wonderful it made him feel to see the story. He appreciated knowing his great grandpa’s history was written down and preserved.”

Meadows develops strong bonds with interviewees when uncovering their contributions to code talkers’ legacy. Three have even adopted him into their families.

“The more you invest in people, the more they’re going to invest in you,” Meadows said. “And your work will be richer for it.”

Leave a Reply