Archive for 2022

Businesses with a cause engage consumers

These companies are cause-driven businesses, created to tackle social challenges while selling goods or services. As Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus said, a social enterprise is, “The new kind of capitalism that serves humanity’s most pressing needs.”

How do consumers feel?

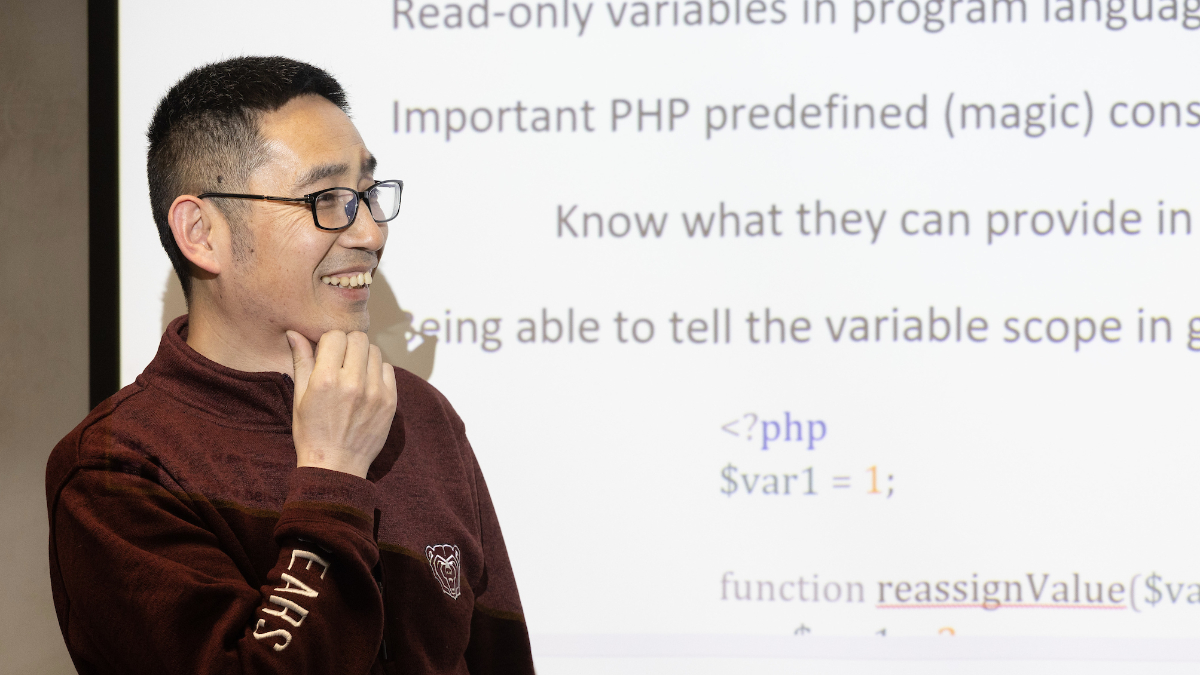

Social enterprises have been the focus of Dr. Josh Coleman’s research since he started his PhD in marketing in 2013. They intrigued him because their mission to better society aligned with his own desire to make the world a better place.

“Today, social enterprises are everywhere. But 10 years ago, they were quite new,” said Coleman, associate professor of marketing at Missouri State University. “So, not only was it a niche I was passionate about, but there was an opportunity to make an impact in an area that didn’t have a lot of traction yet.”

The most common thread in his research is how consumers feel about social enterprises. To find this out, Coleman surveys consumers through online panels. Some include technology like eye tracking.

“Not to sound sappy or mushy, but the consistent theme of my work is, can we make the world a better place to do business?”

He has also traveled overseas and discovered firsthand how social enterprises work in different parts of the world.

He notes consumers have a wide range of feelings about these types of businesses. Some support the ideals of giving back and improving society. Some don’t care as long as they get good products. Others are skeptical.

“Most of what I look at is the idea of communication,” Coleman said. “How does a company communicate authenticity to consumers, so they buy into the mission and the product?”

Which type of message to use?

Coleman has published more than 15 articles and a book chapter. Besides social enterprises, he covers related topics like cause-related marketing (CRM).

“As a professor, I’m not just here to grade my students’ exams and give them assignments. I want to teach them the value of honesty and integrity in advertising, which is something that’s sorely lacking today.”

His latest paper was featured in the Journal of Business Strategy. It explored communicating authentic motives through social enterprise advertisements.

For the study, Coleman presented four sets of ads in varying combinations through internet surveys. The ads contained messages with either giving cues (e.g. giving back clean water to the world) or selling cues (e.g. selling the best coffee in the world). Which ones did consumers find more authentic?

“In general, giving is always going to be more effective in communicating authenticity,” Coleman said.

He adds that if social enterprises present both giving and selling messages together, they will likely enjoy higher sales. But consumers may perceive their giving message as less authentic.

“Ideally, social entrepreneurs should just focus on the giving,” Coleman said. “And if they can’t, don’t try to shoot for the stars with authenticity. They’re never going to get there because there’s always going to be some skepticism of why they’re doing both.”

Pride vs. guilt appeals

Another paper Coleman published in the Journal of Advertising stemmed from his dissertation. It looked at which emotion – pride or guilt – is more effective in CRM advertising.

“Do you want to capture people with your vision or do you want to make them feel bad?” he said.

He approached the project with the assumption that most people would think pride was better. But the data he gathered showed that in some cases, guilt worked well.

“It comes down to, can a company align its message with its target audience? Because people are wired differently,” Coleman said. “Pride’s going to work sometimes, guilt’s going to work sometimes. It’s all about which emotion is right in the right context.”

Inspiring students

While publishing his research is rewarding, what matters more to Coleman is making it relevant to his students. It’s exciting for him to share his passion for this area with them.

“I can give them the theory, the research, the data and help inspire them to make the world a better place together through business,” Coleman said.

Dr. Steve Castleberry, a collaborator on several projects, highlights how Coleman also gives students hands-on learning opportunities.

“He has a social enterprise advertising project in one of his classes every semester,” said Castleberry, marketing and business ethics professor at University of Minnesota Duluth. “Not only is he advancing the academic world; he’s also sharing that knowledge with his students in a very meaningful and engaging way.”

Further reading

-

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Building leaders, one step at a time

Get ready for the sound of brass, percussion and wind. The sight of students forming shapes, one step at a time. Maybe the buttery taste of stadium popcorn and the touch of a crisp, October breeze whispering across your cheek.

But months before, in the muggy heat of a summer day in southwest Missouri, the first thing Dr. Brad Snow notices at Wehr Band Hall is the smell – staunch evidence of his students putting in the work to create a great show.

“When I walked in here this morning, this place already smelled like band camp,” said Snow, associate professor and director of athletic bands. “You know, it’s like a mixture of sweat and sunscreen. They’re not soft, man. They work hard.”

In order to have a synchronized, flawless performance, the Pride Band practices tirelessly.

The question that drives Snow: How will marching band students be better musically, physically and emotionally at the end of a season?

“I think that’s just what drives them,” Snow said. “They don’t do it because it’s easy. They do it because they like to work hard, and they know all the work is going to pay off.”

An educator for 30 years, Snow performed in the Quantico Marine Band. He’s also presented twice at a national symposium for college band directors, adjudicated more than 40 marching band competitions and conducted four times at the Missouri Music Educators Association Conference.

“As we continue to transition the culture of this program forward, the things Brad’s done with athletic bands have just been transformative.” – Dr. John Zastoupil

Members of the Pride Band now get updated coordinates delivered directly to their phone.

Marching toward the future

It’s hard to fill the shoes of a local legend, as Snow did when he succeeded Dr. Jerry Hoover as director of athletic bands in 2016. But since that time, Snow has thrived in helping the 300+ members of the Pride Band advance, while maintaining the group’s strong sense of tradition.

For example: The days of printing thousands of pages of drill sheets and music are no more.

“We have to keep up with what the students are into, make sure we’re kind of speaking their language and doing things in a way that they are used to responding to.”

In 2020, the Pride began using mobile apps to show them where to stand and what notes to play. With Ultimate Drill Book, students can interact with live field coordinates, access optimal pathways to their next spot and link sheet music to their drill, all from their phones.

“We’re able to learn more quickly now,” Snow said. “I’d say it’s allowed our drill to become a little bit more involved.

“We can make edits on drill, the students hit refresh on their app, and they automatically have the new coordinates. So it’s given us more flexibility to make changes and help students prepare for rehearsals ahead of time.”

Moments before a performance, Dr. Brad Snow and members of the Pride rehearse the music in their minds.

As one of the few that performed shows in fall 2020, Missouri State is on the front end of this paperless revolution for bands. For students, it’s made the process easier and allowed them to access familiar technology.

“They don’t have to worry about organizing 50 pieces of music and deal with gigantic flip folders, you know? I select a song, and boom. The music for 300 people changes simultaneously.”

More than music

Snow’s experience playing in the Marine Corps Band and participating in conferences and symposiums has informed his teaching and performance style.

Snow and his team run the Pride Band with principles from the Marine Corps. That includes maintaining a strong chain of command and empowering students with skills to, one day, become the teacher.

In 2013, Snow’s national symposium presentation in Norman, Oklahoma, focused on his approach to leading students.

“The Marines use a manual called ‘Principles of Marine Corps Leadership,’” Snow said. “I went through it, found every mention of ‘Marine’ and replaced it with ‘band.’”

Musicians can access the latest changes to performances on their phones.

To paraphrase one section from the manual: ‘Your appearance, attitude, physical fitness and personal example are all on display daily for the band members in your unit. Remember, your band members reflect your image!’

The amount Snow cares about his students’ development is evident, said Dr. John Zastoupil, associate professor and director of concert bands.

“We talk about this a lot. I think the most special thing about the band program is that we treat it like a family,” Zastoupil said. “When Brad and I are recruiting, we love to tell people about the culture. It’s a network of thousands of band alumni. Our purpose is that we’re here to build people.”

That’s the important big picture for Snow, who counts longevity as his greatest career achievement. His secret? Celebrating a shared love.

“We do this because it’s fun,” Snow said. “And along the way, we learned about working hard as a team and what synergy is all about, even if we didn’t learn these five pages of drill today and we’ll have to really get after it next time.

“Ultimately, at the end of the day, it’s just what we love.”

Further reading

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle

Connecting the rocks to tell the Earth’s story

“This is one of the reasons you become a geologist if you grew up in the 1980s,” Dr. Matthew McKay said as he displays a video of him standing atop Mt. St. Helens.

McKay, associate professor of geology at Missouri State University, mixes old school techniques of mapping and “disappearing into the woods” with the latest technology. It’s a passion, but there’s also important work to be done.

Much of McKay’s work searches for understanding of how and why mountains form, and how long it takes so he can build timelines for those sequences.

His research team, which includes undergraduate and graduate students, also identifies the environmental effects of creating these mountains.

This involves sediment testing, identifying the isotope geochemistry of rocks and radioisotope dating of sand grains. These techniques reveal more about the age and composition of dirt, rocks and sand.

“The trick is, if you take hundreds of samples of individual sand grains and age them, then you can figure out where they potentially came from,” McKay said. “Find a bunch of 50-million-year-old sand grains? Find a rock that’s 50 million years old somewhere in the mountains. Then you can connect them or make tectonic interpretations.”

Affecting industry

Oil and mining companies have deep interest in – and deep pockets for – uncovering this type of geological timing.

“Erosion always wins, so the Rockies will be sad little mountains eventually.”

Why? Tectonic movements disrupt the ground where valuable natural resources exist. Knowing when these movements happened can determine whether oil is where these companies expect it to be.

“The timing might determine whether the oil shifted left or right or if oil is even in the ground anymore. If the timing is not right, then the oil might have migrated up and been lost to the surface,” McKay said.

The information also is priceless for environmental protection, engineering and agriculture.

“If you’re chunking sediment into river systems, that messes up your dams, which may prevent sediment from moving down the river where it’s needed,” he said. “Maybe a fault line means the groundwater can’t move properly, and it’s now contaminated with any number of things.”

McKay’s team also specializes in making geologic maps. The maps are used by many groups, including:

- Environmental agencies when spills occur.

- Exploration companies to locate geologic resources.

- Engineering teams when building new infrastructure.

Movement is the foundation

A recent finding surfaced regarding the southern Appalachian Mountains in Alabama. There, 420-million-year-old sand grains were discovered. But nearby rocks – and even faraway rocks – weren’t matching up in age or composition.

Previous geologists had erroneously linked the sand to rocks in Maine, but that wasn’t lining up for McKay. The more that he and his team worked in this area, the harder it was to reconcile their findings with statements from previous studies.

After collecting samples from across the southern United States and discovering large fossil logs, they determined the area must have been a barrier island at one point. However, using high precision dating techniques, they still didn’t find a match.

Then, McKay’s team considered what the area used to look like. For instance, the Yucatan Peninsula previously sidled alongside the southern U.S. coastline. Now it’s in Mexico.

“The foundation of the science of tectonics is that things move,” McKay said. “It took us a minute to realize it, but the 420-million-year-old rocks aren’t in the U.S. anymore. They’re in Mexico now.”

McKay partnered with a colleague from the University of Memphis to explore further.

Using the crater that killed the dinosaurs for another purpose

Several years ago, the Integrated Ocean Discovery Program drilled along the edge of the Chicxulub crater. This is the crater formed by the asteroid that ultimately caused the dinosaurs’ extinction. A team at the University of Texas published the ages of sand from the impact, and they, too, contained 420-million-year-old grains.

This further confirmed that the sand discovered in the Appalachians was now in Mexico. McKay said that makes sense timing- and location-wise.

“It’s hard to tear down something simple. Something complex, you know, that falls apart fast. But all of this is super simple.”

Geologically, it’s also easier to explain how rocks and sand could travel from Alabama to Mexico than from Alabama to Maine.

“They’re very deeply buried, but they’re down there. They would have been exposed at the time, but no humans have ever seen them.”

Another surprise bubbled up while McKay’s team tested the samples to see when the rocks cooled to a certain temperature.

“We started getting 350-million-year cooling ages on some of the rocks in the Appalachians,” he said, “which means that the Appalachians started about 50 million years before we thought they did.”

Both of these findings were published in a 2021 article in Geosphere, an industry journal. It’s just one of more than a dozen publications he’s co-authored with his students and other colleagues since 2015.

“I appreciate how Matt has taught me to be an independent worker and problem solver, along with providing me the room to grow as a scientist and as a leader,” said Madeline Konopinski, ’21 alumna.

Now a PhD student at the University of Memphis, Konopinski continues to collaborate with McKay on mapping and sediment projects.

Future of the field

The field of geology, which began with boots on the ground, continues to advance.

Now, it includes chemistry, drone technology, laser-assisted topography, 3-D printers and virtual reality (VR).

According to McKay, the future of geology depends on getting students excited about the field.

Part of his plan includes developing immersive VR experiences for students in early geology courses.

“Let them take a trip to terrains worldwide and discover the landscapes for themselves,” he said. “In the snap of a finger, you’re there.”

Once students seize these opportunities, the world grows bigger and the career paths are endless, according to McKay.

“Every time we go out, we find stuff that’s just never been found before,” he said, “which takes us on a new adventure.”

Further reading

-

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photo by Abby Momberg

A big one: Forecasting future volcanic eruptions

It may erupt suddenly and violently terrorizing the town nearby, setting forth panic and destruction.

It might slowly ooze. And another volcano might lay dormant for several more years – centuries even. It’s nearly impossible to predict.

That is one of the goals of Dr. Gary Michelfelder’s research.

For the last 15 years, Michelfelder, associate professor of geology at Missouri State University, has studied the Rio Grande Rift and the Andes Mountains in Chile. He studies magma, volcanoes and the Earth’s crust to learn more about how and why volcanoes erupt to improve forecasting.

He’s also fascinated by the landscape and what ripple effects these eruptions cause.

Student Oluchi Nweke examines a rock with a hand lens during a field trip to the St. Francois mountains in southeastern Missouri.

What do the rocks tell us?

While you may never see lava firsthand, it changes the atmosphere and our world.

As lava cools, it becomes igneous rock, which preserves the history of the eruptions.

“I mainly look at volcanic systems as snapshots in time to record the continental crust,” Michelfelder said.

These magmatic systems – each unique in physical stature and behavior – damage and disrupt more than the terrain.

“I was lucky enough to get to go to a conference in Japan that just happened to coincide with the volcano erupting.“

According to Michelfelder, the gases emitted can change climates or reduce agricultural yields.

“These studies give us insight into understanding our planet,” he said. “We can see why life is here compared to maybe life on another planet, or maybe lack of life in another climate.”

Being outdoors is the best way to learn about the phenomena Dr. Gary Michelfelder studies. Here, student Carl York consults Michelfelder about a finding.

Struck by the geology bug

From a kid who participated in geography quiz bowls, to a young Army soldier stationed in New Mexico, Michelfelder has always wondered why.

“Why are we sitting in this big flat, open area? How is there a 10,000-foot mountain just a mile away?” he said. “It pushed me to understand the landscape around me.”

As his career in the National Guard and in academia grew, so did his ability to satisfy his curiosity. He has produced more than 20 publications in the last decade.

His current quest is to unveil the mysteries of magma. The National Science Foundation awarded more than $230,000 in funding for this latest research endeavor.

In April 2022, Dr. Gary Michelfelder took student geologists to the St. Francois Mountains to study the formations.

For scope, the Central Andes has at least 15 volcanoes the size of Yellowstone National Park. He is looking at an arc of volcanoes that reside atop a regional magma body. It is a reservoir roughly the size of Missouri.

Michelfelder and his research team, which includes graduate students and collaborators across the globe, are trying to understand if this magma body feeds all the volcanoes. They also want to know:

- How volcanoes accumulate the magma.

- How long the magma stays in one location.

- If the reservoir causes powerful eruptions.

“We want to understand the volcanoes in the Andes today versus one million, two million or three million years ago,” he said. “We’re recording the temperature, the pressure and composition of the magma. Then we ask, ‘is it staying the same for each volcano? Is it changing within a stage of a volcano?’”

Dr. Frank Ramos, Johnson Chair of Geochemistry at New Mexico State University, mentored Michelfelder when he was pursuing his degrees. He’s been impressed with Michelfedler’s ability to involve students throughout the research process.

“Gary does a great job integrating master student research projects into excellent publications that have significant scientific contributions to our field,” Ramos said.

Each research excursion is ripe for new learning opportunities.

Studying the crystallized minerals

To find the answers they seek, Michelfelder employs many methods. One of them is analyzing the rocks.

He says you can learn a lot by bringing rock samples back to the lab. The team crushes the rock, dissolves it and analyzes the chemical composition.

“Even though the volcano may not look like a volcano anymore, and it may not be erupting currently, it is an active and dangerous environment. Every volcano is its own animal, so to speak, and it behaves differently every time it erupts.”

These rocks also are enriching teaching tools in his classes, Michelfelder noted.

Using a mass spectrometer, his team tests individual mineral grains. This technique uses a laser to discern the chemistry.

They work with Dr. Lawrence Horkely, a professor at the University of Iowa, to date the rock samples using highly sensitive equipment, which allows for precision in dating eruptions. It also can help identify how long the rock was in the magma chamber prior to erupting.

“It’s powerful to put together a detailed history of what a mineral experienced from the time that it was formed as magma, to the time it erupted at the surface,” he added.

Prior to COVID-19, Michelfelder started incorporating new technology into the project. He took student researchers to Chile to fly drones into the crater of the volcanoes to map the plans for the project.

Due to COVID-19- related travel restrictions, this became impossible. Instead, Michelfelder partnered with Dr. Felipe Aguilera, the director of the Central Andes Volcano Observatory, to gain data from his drone work.

“He takes gas measurements to help us with the volcanic hazards component of our projects,” Michelfelder said. “Our team will be able to explain what triggers the eruptions. His drone data will help us to understand the actual eruption.”

Surrounded by the beauty of the outdoors, student Sarah Peterson takes notes on the geology of the mountains.

Magma on the move

By investigating all these factors, Michelfelder and his team hope to better forecast the level of devastation to expect out of future eruptions.

At the site in the Andes, the team’s findings reveal the magma isn’t staying in any of the stages long before moving.

“We thought it might be residing for a hundred thousand years or more. Instead, the initial conclusion from evaluating the first two volcanoes is that it’s an ever-changing system,” he said.

What’s the downside of this early finding?

“We don’t have the long history of what’s going on there to be able to forecast what might happen in the future. Every eruption’s been different. It makes it difficult to say, ‘this is what this volcano will behave like in the future.’”

Difficult, yes. Worthy of continued research? According to Michelfelder, “absolutely.”

Further reading

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

From the ground up: Nutrition starts with soil

Soils can be enriched with nutrients to grow strong, healthy grass for livestock to consume. Many of the nutrients transfer to your plate when you eat meat, or the fruits, vegetables and grains harvested.

Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, associate professor in the Darr College of Agriculture at Missouri State University, has conducted many research projects focused on the chemistry and nutrition in soil.

“I’ve always loved plants. My father worked for John Deere, so agriculture was part of our family.”

In recent years, the agriculture community has emphasized the importance of testing soil composition then improving the chemistry. Farmers may do this by adding nutrients to the soil or to the solution that waters the field.

“Not only can you grow more food, but it’ll be healthier. And in turn, you might not have to add supplements to your cattle’s food,” Bledsoe, a plant physiologist, said. “By investing a little bit more in your soil, you can get a better benefit.”

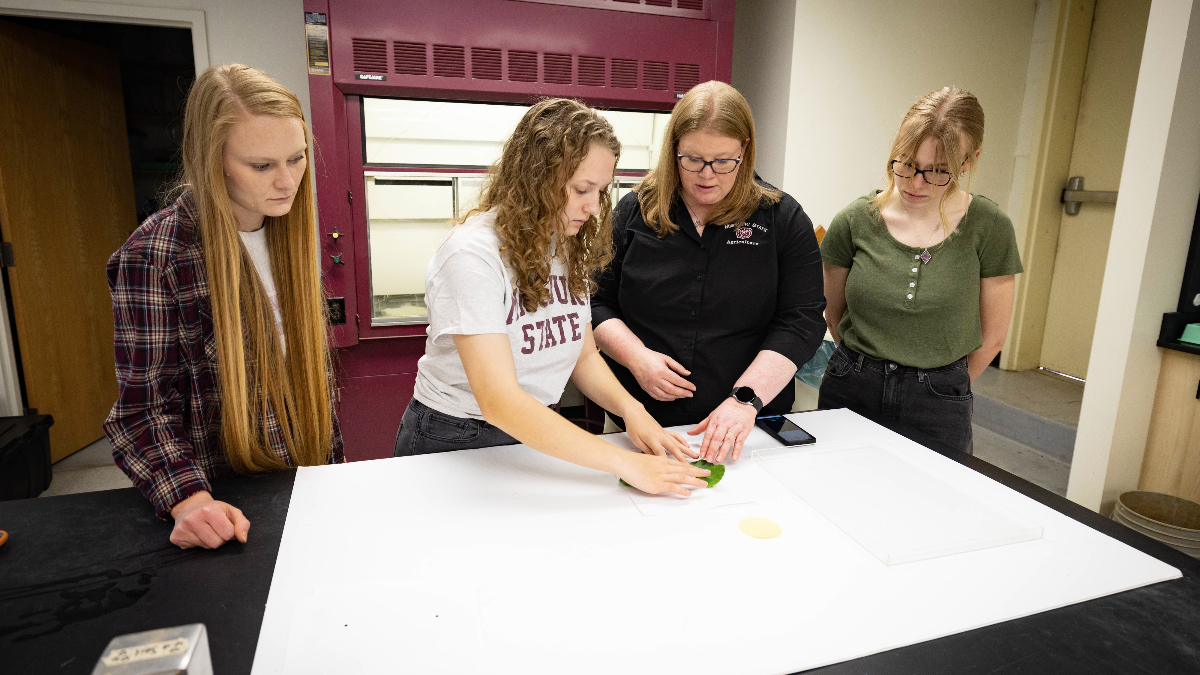

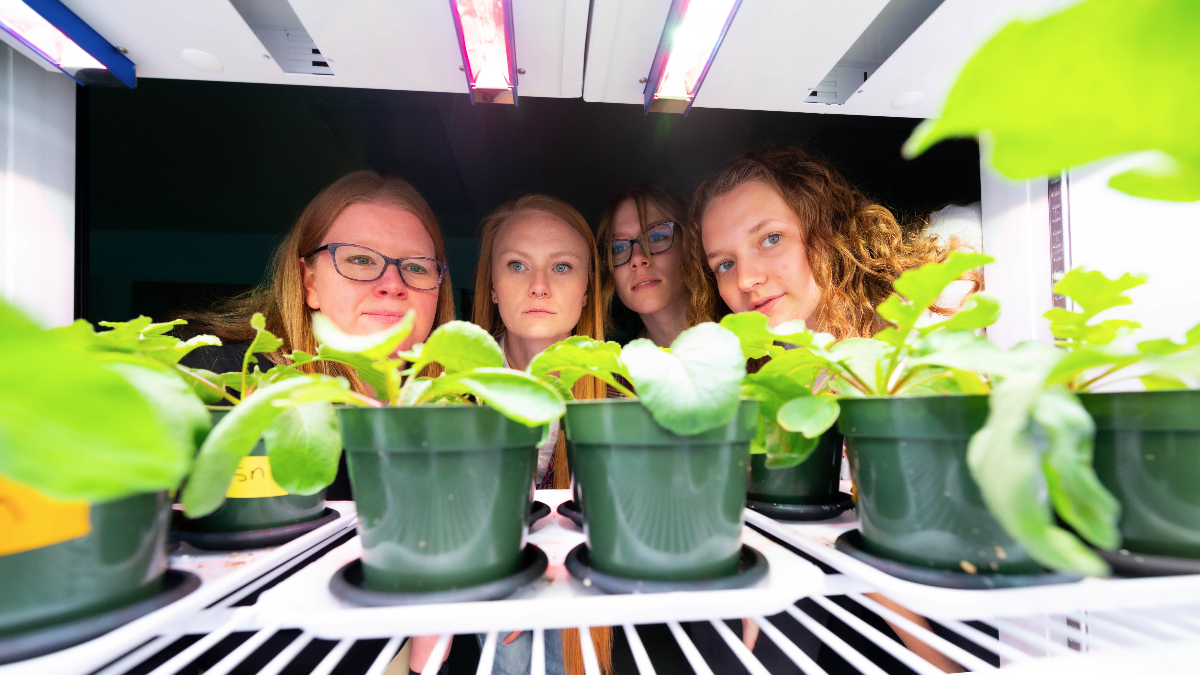

Horticulture student Gwenyth McClain works under Dr. Melissa Bledsoe, learning to test soils and plant tissue.

In Karls Hall at MSU, Bledsoe teaches her students to test soils and plant tissue. These tests can show how soils need to be adapted to meet the goals for the crop.

Bledsoe integrates research into her teaching, and she values building projects around her students’ interests and questions.

She relates this back to her own experience as a graduate student studying under Provost Dr. Frank Einhellig. He inspired her to dig deeper into research and ultimately pursue her doctoral degree.

A finding about phosphorus

Grass tetany, a fatal disorder in cattle, is related to low magnesium in a cow’s diet.

In previous work, Bledsoe and colleagues found soil must have adequate phosphorus levels for magnesium to reach the leaves of tall fescue.

“The Ozarks has acidic soils, which means our phosphorus levels are low,” she explained. “Grass tetany is more of an issue in our tall fescue pastures than in many other places.”

This led to another study, and another publication in 2019. This time, the team focused on other common crops, such as winter wheat, oats and cereal rye.

Students are an integral part of Dr. Melissa Bledsoe’s lab.

Starting small, her students set up the experiment in hydroponics. This allowed them “to manipulate the mineral nutrition very specifically to see how the plant responds.”

Then, they expanded the study to the field, hoping to zero in on how adding phosphorus to the soil affected the magnesium in the winter plants.

“Our abilities are flexible. So when a student says, ‘I’m really interested in growing vegetables,’ we think about a way we can solve a question about that.”

While winter wheat was responsive to the addition, the other winter annuals were not.

Though the study didn’t indicate that there were benefits for the other winter annuals, Bledsoe spins it positively.

“Even finding that some plants don’t respond is still an answer,” she said, noting that it’s a learning opportunity for students. “It gives them a reason to continue testing the techniques with other variables, too.”

Students Mary Books, Sarah Overbeck and Gwenyth McClain work to gain greater understanding of how to improve crop production.

Establishing a silvopasture

At Journagan Ranch, a Missouri State property in Mountain Grove, Missouri, Bledsoe has worked alongside Drs. Michael Goerndt, William McClain and Toby Dogwiler on a major U.S. Department of Agriculture grant project since 2018.

Here they have established a silvopasture to study.

In simpler terms, a silvopasture means you’re optimizing land to grow trees and grass together in a way that benefits both to get higher yields.

“We want to grow forages for grazing cattle in this area. If we can grow forages under trees, we can get a second crop with trees,” Bledsoe said. “Meanwhile, we’re providing shade and cooler temperatures for the cattle.”

It takes a long time to establish these plots before they are producing at full capacity, Bledsoe stressed. All along the way, the team monitors and measures tree health, soil nutrition and forage growth for baseline data.

“We can map the area but also monitor how those trees are growing, how the grasses are growing and see what stresses they’re under. Ultimately, over time, we can also monitor production and growth with drone flights, and we’ll have on the ground measurements to compare that to.”

In Dr. Melissa Bledsoe’s lab, she uses growth chambers to ensure stability of variables.

As the roots deepen and the trees thrust upward, the team will continue to track at periodic tipping points throughout the year:

- At the end of winter, before the plants bud and leaf again.

- After stress from a drought.

- Before the leaves wither and fall.

Learn more about the silvopasture project

“We want to prove how a silvopasture system can benefit a producer and how these systems might help the trees and forages be healthier,” she said.

Helping farmers

In her role, Bledsoe mentors students in agronomy and horticulture. Her interest in soil health and nutrition serves as a springboard for a broad range of students to jump into research, she noted.

“We have students that range from horticulture to agronomy and we want to have all those students be interested in research.”

Her projects dig in many different directions – garlic, microgreens, and fescue to name a few. At the root of each, she sees a commonality.

“We’re trying to help local producers have healthier soils and healthier forage production, so they can have fewer issues with their cattle,” Bledsoe said. “For me, I love working on real world problems that can alleviate the pressure on these producers.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Further reading

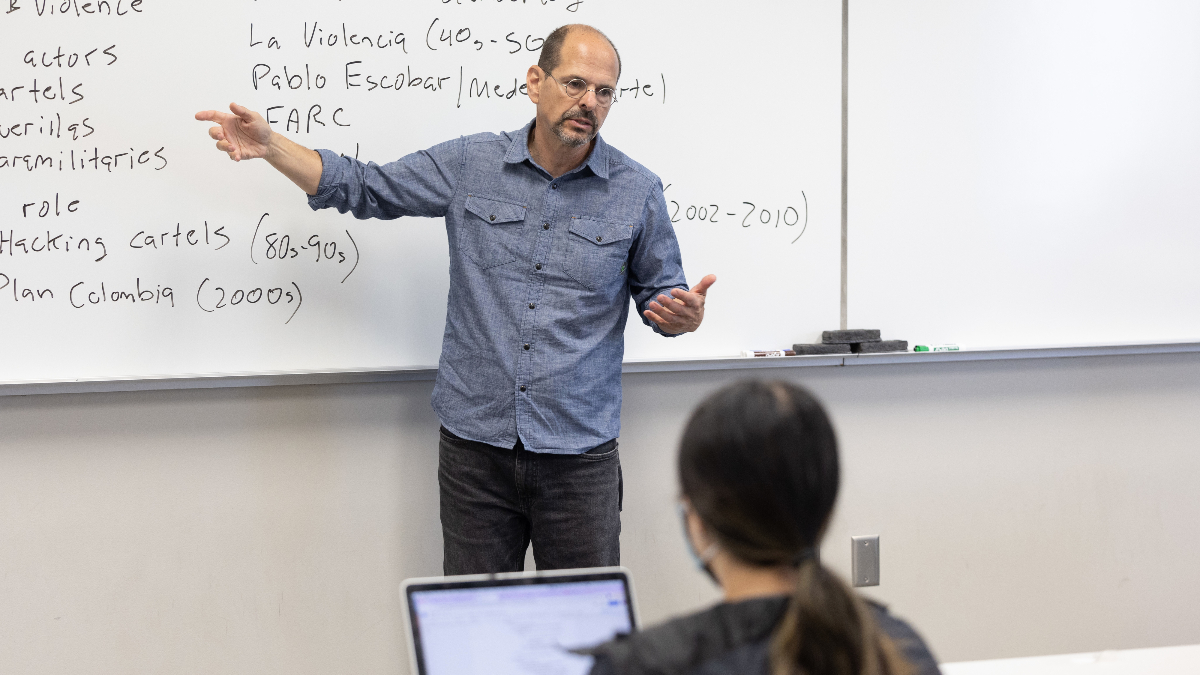

Taxes in Latin America: More than dollars and cents

Perhaps a third item should be added to the list, Dr. Gabriel Ondetti says: People believing they pay too much in taxes … especially in the United States.

“When you tell them what the data says – that they’re very lightly taxed compared to people in other countries – they’re astounded,” Ondetti said.

An expert in Latin American politics and taxation, Ondetti has published two books, authored more than 30 conference papers and contributed eight articles in refereed journals. He is the Clif and Gail Smart professor of political science and director of the Master of International Affairs program at Missouri State University.

His central research question is: Why do some countries tax their citizens more heavily than others?

“A lot of people find taxation boring because it can be highly technical,” he said. “But it’s a political process. You can understand many other things about a country by studying taxation.”

Student Tracy Ramirez poses a question to Dr. Gabriel Ondetti.

Uncovering the roots of taxation in Latin America

In 2021, Ondetti published “Property Threats and the Politics of Anti-Statism: The Historical Roots of Contemporary Tax Systems in Latin America.” The refereed work won an award from the Latin American Studies Association and delivered outcomes from Ondetti’s qualitative research, including more than 80 interviews with politicians, business leaders, and other decisionmakers.

Ondetti’s parents immigrated to the United States from Argentina in 1960. That sparked his interest. Some of the key questions came about during his 10 years of work on taxation in Latin-American countries. Why is taxation heavier in Brazil than Chile? Why is it heavier in Argentina than in Mexico?

“If you’re a political scientist, you can’t really ignore taxation. Whatever government does, they have to have money to do it.”

Using a qualitative and comparative historical method, Ondetti found that countries with lower tax rates tended to be countries that historically threatened private property by seizing land, oilfields, factories and other assets on a large scale.

A redistribution of property rights in favor of the poor, Ondetti says, resulted in a long-lasting political backlash from the wealthy.

“The very act of redistributing property through land reform and nationalization of private industries inspired strong anti-government ideologies, particularly among elite sectors of the population,” he said.

But lower taxes mean less public funding for items such as education, social programs and infrastructure, which creates something of a paradox, he said.

“It’s kind of ironic, you know? The places where people sought the most progressive change became the places that created the greatest obstacles to change.”

Ondetti’s work is special in many ways, according to Dr. Gustavo Flores-Macías, associate vice provost for international affairs and associate professor of government at Cornell University. Flores-Macías shares the same research interest and is familiar with Ondetti’s book.

An expert in Latin American politics and taxation, Dr. Gabriel Ondetti has published two books, authored more than 30 conference papers and contributed eight articles in refereed journals.

“I think research into taxation has been dominated by economists for the most part,” Flores-Macías said. “Two of the great things Gabriel does is explore how to make taxation politically palatable and focus on explaining differences within Latin America.

“Several people have written about Latin American taxation compared to European countries, but it’s a lot more complex to look within a region. He does careful, historical tracing of the reasons behind those differences.”

Taxes in the United States: Not as high as you may think

People from every country think their taxes are too high. That’s especially true in the United States, Ondetti said, where citizens have little idea how their taxes compare to other countries.

“The tax system for many countries is deeply intertwined with a whole series of other factors that shape their culture and politics.”

Taxation is essential for countries everywhere to provide services, but the questions governments must answer include: Who’s going to bear the burden? To what extent will those people rebel, and what consequences could that bring?

“That even includes Mexico, which has the lightest tax burden of all the countries that I studied. Everybody there thinks they have very high taxation,” he said.

As an example, Ondetti notes that the United States has one of the lowest tax burdens among all developed countries. It’s equal to about 24% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country during one year.

By comparison, Denmark’s tax burden compared to their GDP hovers around 45%.

“Yet, there are probably more people in the United States who feel they’re overtaxed than there are in Denmark,” he said. “That’s a subjective judgement, which they have a right to. But in comparative perspective, it just isn’t true.”

- Story by Kevin Agee

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Mice population models much bigger picture

However, this animal struggles to survive through harsh winters.

Tracking the population size and location of this mouse can serve as a “bellwether for climate change,” said Dr. Sean Maher, associate biology professor at Missouri State University.

“My graduate advisor shared his research on the animal, and got me hooked on small mammals,” Maher said.

Dr. Sean Maher checks traps at Linden Prairie as part of a population study.

Maher studies scurrying mammals, primarily mice and rats, by catching and releasing them. His work is a snapshot in time of where these animals call home and gives an estimate of how abundant they are.

“One of the issues with wildlife biology is that just because you fail to find it doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

The information can be compared to previous or future research of a species or region to provide evidence of change or forecast trends.

“These small mammal communities can give us a baseline,” he said. “Twenty or 30 years from now, someone can survey the same prairie or glade and compare data. Then, you may see a different story – perhaps a species disappeared or a new species is present.”

Graduate students Sofia Orlando, left, and Emilyn Gilmore, right, flank Dr. Sean Maher during a population study.

Rare vs. not there

Maher’s work focuses on wildlife biology using statistical modeling and geographic information systems. The computer scripts he develops can answer questions about species dispersal 20,000 years ago or current species occurrences in a local glade system.

Emily Beasley, a 2018 MSU alumna and now a PhD student at University of Vermont, surveyed four glade systems for her thesis:

- Bull Shoals Field Station.

- Roaring River State Park.

- Mark Twain National Forest.

- Caney Mountain Conservation Area.

In each of those areas, she set traps in three to four glades of varying sizes to examine what species lived there.

Beasley co-authored an article with Maher on this research and published it in the Journal of Mammalogy. Based on this work, she was the recipient of the Annie M. Alexander Award from the American Society of Mammalogists, and it provided strong evidence of island biogeography theory.

“The most rewarding thing is seeing the students getting where they want to go. And I’m gratified when they can use me as the stepping stone to their career.”

At its root, this theory states larger islands have more species; smaller islands have fewer. An island, in this sense, simply means an isolated area.

Mice like these are at the center of Dr. Sean Maher’s studies.

“If it’s a really good year, you’re going to see more species. That’s what happened with Emily the first year; she was picking up extra species,” Maher explained. “If it’s a bad year, you’re going to get fewer species.”

Maher and Beasley’s work showed the counts could suffer or swell based on environmental disruptions. A good year for small mammals usually comes with more rainfall, causing trees to produce more of the mammals’ favorite meal: seeds.

In planning out the project, Maher advised Beasley to use a statistical model that accounted for detection of rare species.

“Her work was novel because it simultaneously accounted for whether you’re going to find a species and whether or not it’s there. You have to account for both of those things to get a good idea of presence,” Maher said. “If you’re catching a bunch of rare species, there are probably even more rare species that aren’t being sighted.”

Student Sofia Orlando documents her findings as she examines the prairie lands.

Providing a baseline

Maher’s former student, Casey Adkins, is pursuing her PhD at the University of Nevada – Reno. She appreciated his insight, advice and guidance during the application to doctoral programs. Moreover, she appreciates what he brings to the scientific community.

“Sean’s work is unique because he not only studies communities and their interactions, but how these interactions may change throughout time and geographic space,” she said.

In the last decade, Maher published more than 15 articles detailing the lives of animals and parasites we often overlook.

He’s interested in parasites like ticks “because when you talk about small mammals, they are linked to ectoparasites,” Maher said.

Prairies like this are ideal habitats for the animals Dr. Sean Maher studies.

Virginia possums, for instance, feed on ticks. When a region has a healthy population of one, there will likely be fewer of the other.

Maher is quick to say, though, the linkages between mammals and ticks are still being formed. This is the focus of another current study.

Data collection on many regional species and habitats has been lacking. In many cases, the baselines were established within the latter part of the 20th century.

“Collecting data is important,” Maher said. “Just like in the case of the white-footed mouse, data tell us a story about the health of a forest or glade, as well as the climate.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

- Video by Chris Nagle and Megan Swift

Further reading

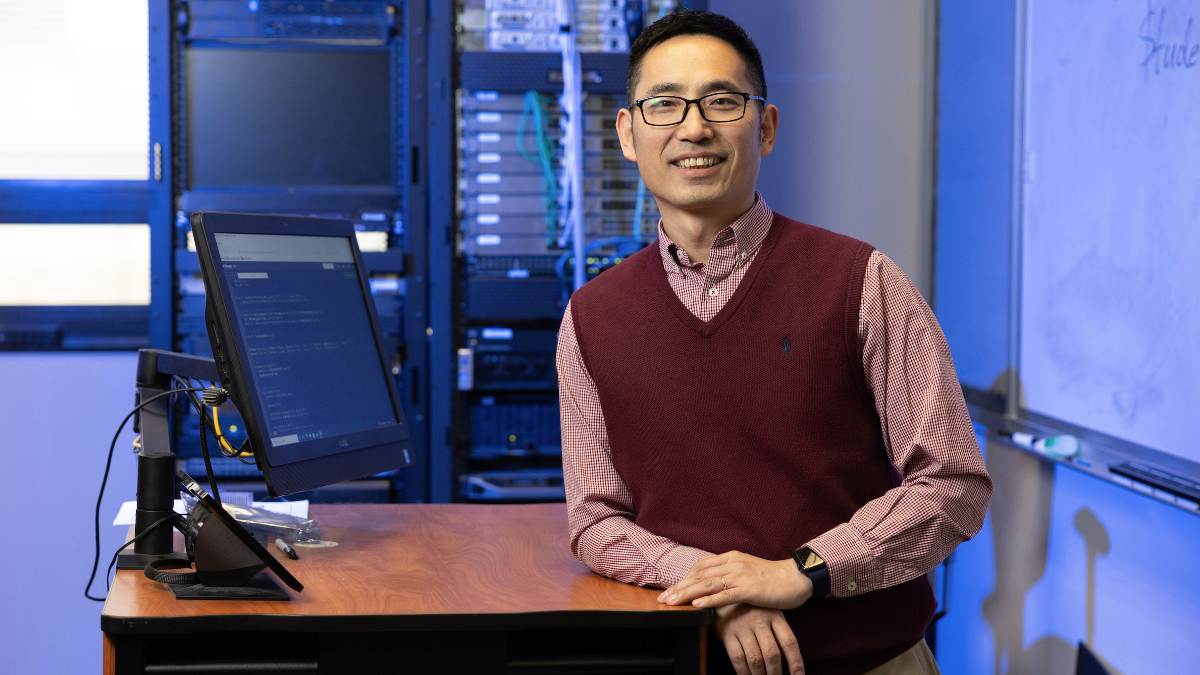

Innovating decision-making

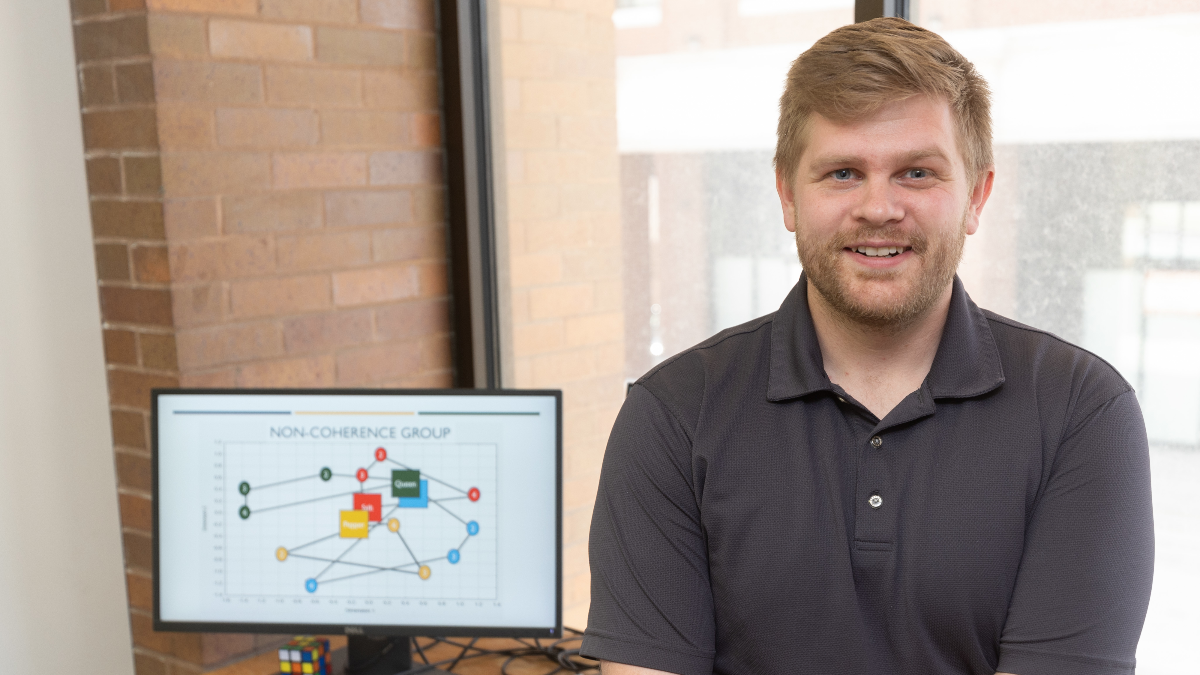

For Dr. Lawrence Yang, an associate professor of information technology and cybersecurtiy at Missouri State University, they go together smoothly.

He explains that artificial intelligence and machine learning can predict human purchasing behavior. One example he uses is how the amount of frosting purchased will drop in conjunction with the spike in cake prices.

“I am interested in applying artificial intelligence to help solve business problems and better predict possible outcomes,” Yang said. It’s an interest that he began to focus on while pursuing his PhD.

“I believe AI has the ability to affect organizations’ decision-making skills in a positive and efficient way.”

Information overload

Artificial intelligence develops systems to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, like decision making.

“Human beings are intelligent and can learn lots of information, but humans only have a certain number of years to learn that information. That’s our limitation,” Yang said. “Artificial intelligence has no limitations. We can insert millions of good and bad examples in these software programs in the matter of a couple of minutes.”

After that, the machine can predict the best course of action, Yang added.

The answer to the question

The answer to the question

Dr. D. Sudharshan, Yang’s advisor and mentor, had a vision about how AI would shape the future. This inspired Yang, setting him on his current research path exploring the use of AI in business decisions.

Over the past six years, Yang has authored and co-authored six publications of research. All his research is centered around how businesses can better use technology to become more efficient.

For his most recent project, Yang focused on a typical business problem called cross purchases. These are products used together – like cake mix and frosting.

“First of all, we already know if you drop the price of anything, consumers are going to buy more of it. That’s a typical economic problem,” Yang said.

When the cake mix price dropped, Yang wondered if consumers would also buy more frosting when they filled their baskets.

But he’s not actually talking about people in a grocery store or sweet confections. Yang uses AI to learn the extent consumers make these cross purchases when one product’s price decreases.

Problems ahead

Yang is not the first researcher to focus on cross purchases in businesses. People have been researching it for years using economic models such as regressions and other statistical models.

“Artificial intelligence nowadays is very popular. A lot of people try to use it in all areas. And there’s many successful stories and exciting stories in natural science and now in business. As we know, artificial intelligence in general is, let a computer learn what we already know.”

But these statistical models are flawed, Yang noted.

“When you add too many dependent variables into these models, it is hard for the computer to give good reliable data,” Yang said. “This is a good place to think about using artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms.”

According to Yang, machine learning can calculate solutions with multiple variables without sacrificing reliability.

Student Linh Nguyen works on a problem in a computer lab.

Time is of the essence

To start his research, Yang obtained data sets from a public database, Nielsen Consumer Panel. Yang obtained raw data that had about 20,000 purchases in that data set.

With this data, he ran comparison tests between traditional models and AI. From it, he discovered something important.

When looking at four variables – like cake mix, frosting, detergent and softener – the traditional econometrics model could perform similarly to AI. In fact, it made the same purchasing decisions.

However, adding four more variables overwhelmed the econometrics model. It took two weeks to evaluate the relationship between those eight variables.

Using those same eight variables, AI and machine learning performed the analysis in only two hours.

“My dream project is artificial consciousness. Someday I can build a AI, so let AI have feelings, let AI able to protect itself, define itself, let AI know what’s the boundary between the AI itself and other counterpart. I mean, that’s my dream project.”

This was a significant learning experience for Yang. It showed just how powerful AI is in terms of bearing the load of big data.

“With this, businesses can use the data in real time and better make business decisions,” Yang said.

Yang is hoping to continue his research in artificial intelligence and learn more about how he can embed knowledge into AI.

“Dr. Yang is a very talented researcher who tackles contemporary problems using a wide range of research skillsets,” said Dr. Joshua Davis department head information technology and cybersecurity. “I am very impressed with the quality and diversity reflected in his research portfolio and am excited to watch it continue to grow.”

Yang plans to push forward his research into the realm of artificial consciousness. This refers to a non-biological, human created machine that is aware of its own existence.

- Story by Jonah Rosen

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Working through differences

It’s true. Teamwork can elevate a project and produce successful results. But it’s also common to hear – or feel – an exasperated groan at the mention of group projects. They can be laborious and frustrating.

“I love exploring these team or workplace interactions – both good and bad,” said Dr. Stephen Spates, assistant professor of communication at Missouri State University.

In his research, Spates works with a team of collaborators and co-authors on two interrelated topics. His primary research deals with how groups form and solve issues in health spaces. His secondary research focuses on how people interact when there is more diversity among group members.

Dr. Stephen Spates poses questions like, “What happens when people from different cultures come together? What do those dynamics look like?”

Forming teams

In many health care settings, these transdisciplinary teams are the norm. Providers come together, share their approaches and give input about individual treatment plans or administrative decisions.

“While the focus from each perspective is a patient’s well-being and quality of life, physicians, nurses, social workers, surgeons and chaplains may attribute more or less value to different factors,” he said. “They ultimately may have very different ideas of what is best.”

In particular, the chaplain’s role has fascinated Spates since his time in health care marketing.

“I focus on workplace relationships when they’re good and when they’re not so good. That becomes the umbrella for my research.”

For a recent research project, he developed a case study about the challenges chaplains face in a team tasked with planning a new hospice-style hospital wing. For instance, chaplains’ opinions may be discounted since chaplains are not medical personnel.

This scenario is the basis for a 2020 published article, which also offers strategies and tactics for overcoming challenges like this in a health care team.

“We see a battle happening as the group struggles to accept and value the traditional medical voices and others equally,” Spates said.

Having tough conversations and finding common ground: that is part of Dr. Stephen Spates motto. He does this in his classes and with his collaboration with Missouri State’s Ad Team.

Strategies for success

To succeed in these transdisciplinary teams, Spates’ article suggested members take time to build the team before tackling the task. This involves building trust and generating understanding about why each person was selected for the team.

Participants should contribute equally to discussion and brainstorming, Spates said. This can eventually help everyone value all the perspectives presented.

Spates also stressed that assignments should be delegated equally to ensure every team member is truly contributing.

“These challenges are common in organizations, but the hospital setting is unique because of the high stakes involved. You’re literally talking about life and death,” said Dr. Catherine Kingsley Westerman, associate professor of communication at North Dakota State University. She is a co-author on this study and a common collaborator with Spates.

“Coming up with some communication-based solutions for those teams was a great contribution.”

Now that Springfield, Missouri, has a chaplain training facility, Spates envisions collaborating on future projects to dive deeper into the experience of the chaplain.

In his Introduction to Health Communication class, Dr. Stephen Spates encourages cooperation within transdisciplinary teams.

Increasing understanding

In his secondary research projects, Spates poses questions like, “What happens when people from different cultures come together? What do those dynamics look like?”

As an extension of this, he teaches a graduate course focused on communication and diversity in the workplace. In it, students discuss taboo topics.

“I like to say, what’s my next exploration, what do I want to explore now? And a lot of the titles of my works talk about exploring relationships.”

Then, they expand their understanding of how to work with people at opposite ends of the spectrum on these topics, which are often value-based.

“We navigate these topics that are part of our identities in different ways,” Spates said. “How do we – in our different perspectives – still work with people and communicate effectively?”

Making it a game

Because of this expertise, it was a natural fit for Spates to consult with Missouri State’s Ad Team in spring 2021. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security charged university advertising teams across the nation to compete to create an integrated marketing plan to prevent radicalization strategies.

MSU’s final project, Fuse, won second place nationally.

“It’s a game that allows people to come together and talk about some of these hot topics in a way that diffuses or deescalates,” he said.

Another reason he thinks Fuse stood out? Games force people to communicate, he said.

Spates employs gamification strategies in his classroom, too. In 2021, he published an article about the effectiveness of games in organizational communication classrooms.

“Games can get through in a different way to students,” he said. “And they can make complex concepts clearer.”

Though Spates is still in the infancy of his career, he’s already published multiple articles and contributed to industry encyclopedia entries and books. Not surprisingly, most of these have been as part of a research team.

“I love having multiple minds come together,” he said. “I want to see my work come out of the journal and jump into real life.”

- Story by Nicki Donnelson

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

What’s behind the psychology of changing behavior?

Human beings use personal beliefs and experiences to elect presidents, spread misinformation and make choices that help and harm the world.

So, how can we use science to make sure humans act in ways that are beneficial to society and the planet? How can we influence and manipulate human behavior?

These are the questions Dr. Jordan Belisle, assistant professor of psychology at Missouri State University, asks in the Humans Understanding Behavior (HUB) research lab.

Dr. Jordan Belisle considers how language relates to perception and behavior.

The answer lies in self-awareness

Belisle studies Relational Density Theory (RDT) and how it applies to human behavior.

“In our autism research, we’re focusing on what it means to be an active learner, strategies for problem solving and how to become someone who is curious about the world.”

RDT explains how language shapes our perceptions and behaviors.

Belisle has applied RDT to studies about climate change and training for children with autism spectrum disorder.

“When we look at the climate change crisis, it’s not a simple equation. It’s not like, ‘If I change my behavior this much, the planet won’t reach the point of no return,’” Belisle said. “Rather, we interact with language, news networks and ecosystems of information. And we tend to only interact with language that adheres to our existing beliefs.”

In an attempt to shift those beliefs, Belisle used a survey based in economics. He tried to determine if people would react to climate recommendations the same way they make decisions with money.

“It’s based off the idea that people are making a transaction with the environment,” he said. “We’re spending the environment now, and the implications of that may be grave later.”

The study showed a correlation between delayed payments and how people respond to climate policies. Just as people would make payments on a loan to avoid paying a large sum up front, people will adhere to policies that delay the climate hitting a point of no return.

“The study opened a door for us to adopt research from behavioral economics. It helps us to predict and influence choices around climate change,” Belisle said.

Student Brittany Sellers works alongside Dr. Jordan Belisle in his lab.

Adapting curriculum for autistic learners

For children with autism, a disorder that impacts language and cognitive processing, RDT tactics prove useful as well.

“We can break a person’s language down into bits and pieces to construct language development through training,” Belisle said.

Belisle led a study during the COVID-19 pandemic that observed relational learning while students were at home.

“Children with disabilities learn best with hands-on instruction,” Belisle said. “But we discovered that teaching relational learning skills is still effective with digital instruction. It just requires some adjustments.”

The adjusted programs include video-based speaker and listener activities, which are fundamental in applied behavior analysis. Children discover meaning in the activities when it’s associated with something familiar, like a beloved movie or book character being used in instruction or memory recall.

“When schools went remote, many families were ill-equipped to provide the curriculum and support students get on-site,” Belisle said. “The video-based adaptations we made make us better prepared should an emergency like COVID-19 happen again.”

Even though keeping the attention of students is more challenging during distance learning, Belisle said that incorporating familiar stimuli makes it easier.

“The more you can build around relations that a child has already learned and incorporate their interests, the more success you are likely to have.”

Dr. Jordan Belisle incorporates students, like Lauren Hutchison, into his research.

Leading projects with student researchers

Much of Belisle’s research interacts with projects of the graduate students in the HUB lab.

Graduate students Meredith Matthews and Elana Sickman work in tandem with Belisle. They have worked on people’s perception of climate change and autism research, among other projects.

“When we look at some of the deepest problems in our world, it comes back to human behavior.”

Both Sickman and Matthews note Belisle’s passion and flexibility. They say he leads student researchers toward discoveries with implications they care about.

“He’s our biggest advocate,” Sickman said. “And we’ve learned in the lab that science and advocacy for the issues we want to fix go hand-in-hand.”

Dr. Jordan Belisle’s lab with students Maggie Adler, Brittany Sellers, Elana Sickman, Lauren Hutchison and Jessica Venegoni.

Help students, help the world

The purpose of collaboration in the lab is to help students grow into independent researchers who use their findings to better the world.

The current group invests in social justice issues, disability advocacy and climate change attitudes and actions. Future students might choose to study different topics, according to Belisle.

“I’m excited to see what the next group is passionate about,” he said. “I hope I’ve developed enough as a professor to meet them in solving our shared challenges in the world.”

Belisle’s bottom line: Using science to make the world a safe, accepting place, where everyone can flourish.

“When it comes to the issues we’re trying to fix, if we can be more scientific, we can better understand why they happen,” Belisle said. “We can use that understanding to engineer a world that allows us all to live the lifestyle that we value.”

- Story by Lauren Stockam

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Mapping the geography of opportunities

Dr. Ron Malega, associate professor of geography at Missouri State University, found this to be the case when growing up in metropolitan Detroit.

His time spent working as a police officer reinforced the perspective.

“Much of my interest in people and places stems from trying to understand this,” Malega said. “I’ve always questioned how could your race or ethnicity make you feel out of place if in the wrong neighborhood?”

Malega’s career path has involved many directional shifts. This includes a move from police officer to professor.

But passion for getting to the source of neighborhood differences has remained a constant in his work.

“In my mind, what brings my varied research interests together is exploring how spaces and places contribute to various quality of life issues and thererby impact the opportunity we have,” Malega said. “I call this the geography of opportunities.”

In his academic career, Malega has authored or co-authored 14 publications on the subject.

Volunteers work on upgrading a housing project with Habitat for Humanity.

Pinpointing divides between demographics

Researchers have found that those of different races and ethnicities tend to live in different parts of town. This is true even if individuals have the same income level.

Why does this so-called residential segregation occur? Studies link it to everything from personal preference to discrimination in the housing market.

Many also point to the role of “white flight.”

This occurs when white individuals move away from urban areas with many minority residents.

“The geographic divide between different groups has declined nationally in recent decades. But it remains strong in many metropolitan areas,” Malega said. “Black and white individuals have historically been the dominant demographics in these areas. The divide is often most visible among them.”

Malega studied differences between neighborhoods segregated as predominantly white and Black populations nationwide. He has also centered research on his home city of Detroit.

The question Malega asks: How does your neighborhood affect your life experience?

In Detroit and nationwide, the answer was the same.

“I found even the most affluent Black households live in lower-quality neighborhoods than white households,” Malega said. “The trend remains even when controlling for the economic ability of the two groups.”

Rethinking “apples to apples”

How do we define neighborhood quality? Malega looks at the social advantages or disadvantages each residential area offers.

He draws from various neighborhood quality indexing systems in his research.

These systems measure many factors of neighborhood quality. This includes:

- Rates of poverty.

- Unemployment.

- Education levels.

- Median household income or house value.

- And many others.

His findings showed major discrepancies between Black and white demographics across these areas. Black households experienced social disadvantages over time and regions.

The results reflect rotten conditions that extend past one bad fruit, Malega explains.

“As community members, it’s easy to see a certain disparity or instance of discrimination and think it’s isolated. It’s a bad apple,” Malega said.

“But with research, we can see there’s a pattern to these occurrences at a higher, structural level of our society.”

Through Dr. Ron Malega’s research, he confronts disparities in opportunities.

Malega takes the analogy of apples further. He argues that we should characterize neighborhoods based on more than income alone.

He aims to show that residential problems don’t always fit the often socially constructed lens of “Black and poor.”

“Comparing apples to apples will show the fruit are not all the same. There are unique variations between each, some influenced by region,” Malega said.

“Similar variations exist among people of the same group. We can’t lump them together.”

Data as driver of social action

Malega’s interests are as diverse as the populations he studies. The full scope of his research covers a wide expanse – from community development to policing issues to park use.

But there’s a uniting goal: to map the opportunities that fuel quality life experiences.

“In my mind, what brings my varied research interests together is the idea of integrated things that reflect quality of life,” Malega said. “I call this the geography of opportunities.”

These opportunities can take many shapes, such as in the form of education options and available public resources.

“Dr. Malega is a man of integrity and sincerity,” Rebecca Stallings, Missouri State alumna and research collaborator of Malega, said. “Working with him on research reinforced for me the value of a degree in geospatial science. He is a true asset to the Missouri State faculty.”

This includes patrol services, which Malega understands the value of given his police background.

“Do you have a police department that responds to every job and is professional? Or do you have a police department that has a slow response time?” Malega said. “The resources you have access to in this regard, among others, stems from where you live.”

Making opportunities accessible to all presents a challenge — one that requires us to move past a history of poor race, social and economic relations.

Malega hopes the data he collects can help fuel change. This includes by providing evidence the public can use to turn their arguments into social action.

- Story by Ashley Lenahan

- Photos by Kevin White

Further reading

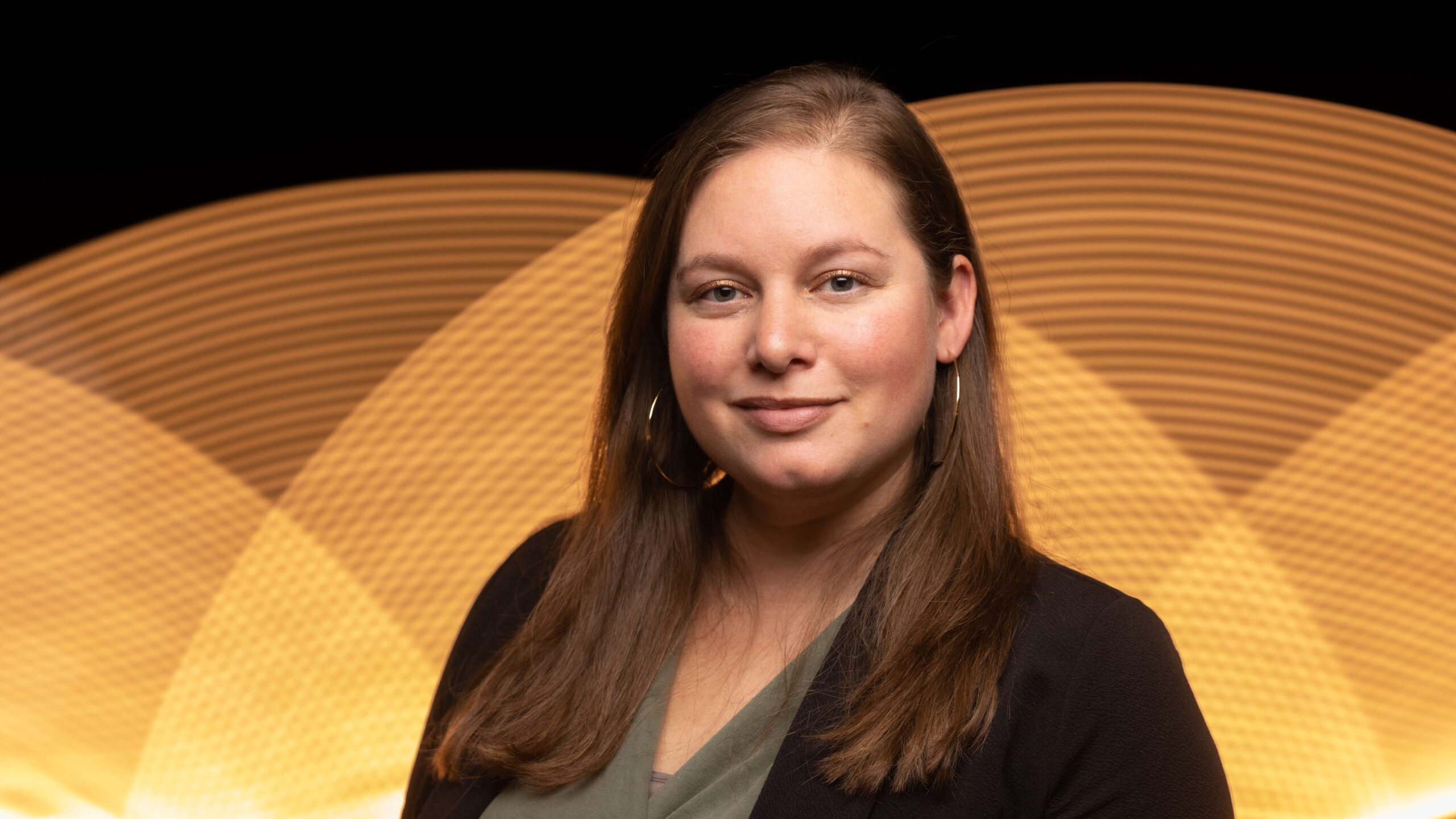

Relating stories of the ancient world

So, it was only natural that Troche, an Egyptologist, chose to study history in college. She delved deep into the realm of ancient Egypt and Assyria in graduate school.

Over the years, she has visited the region several times to conduct research and field work. She has spent time in Abydos and Luxor in Egypt and Petra, Jordan.

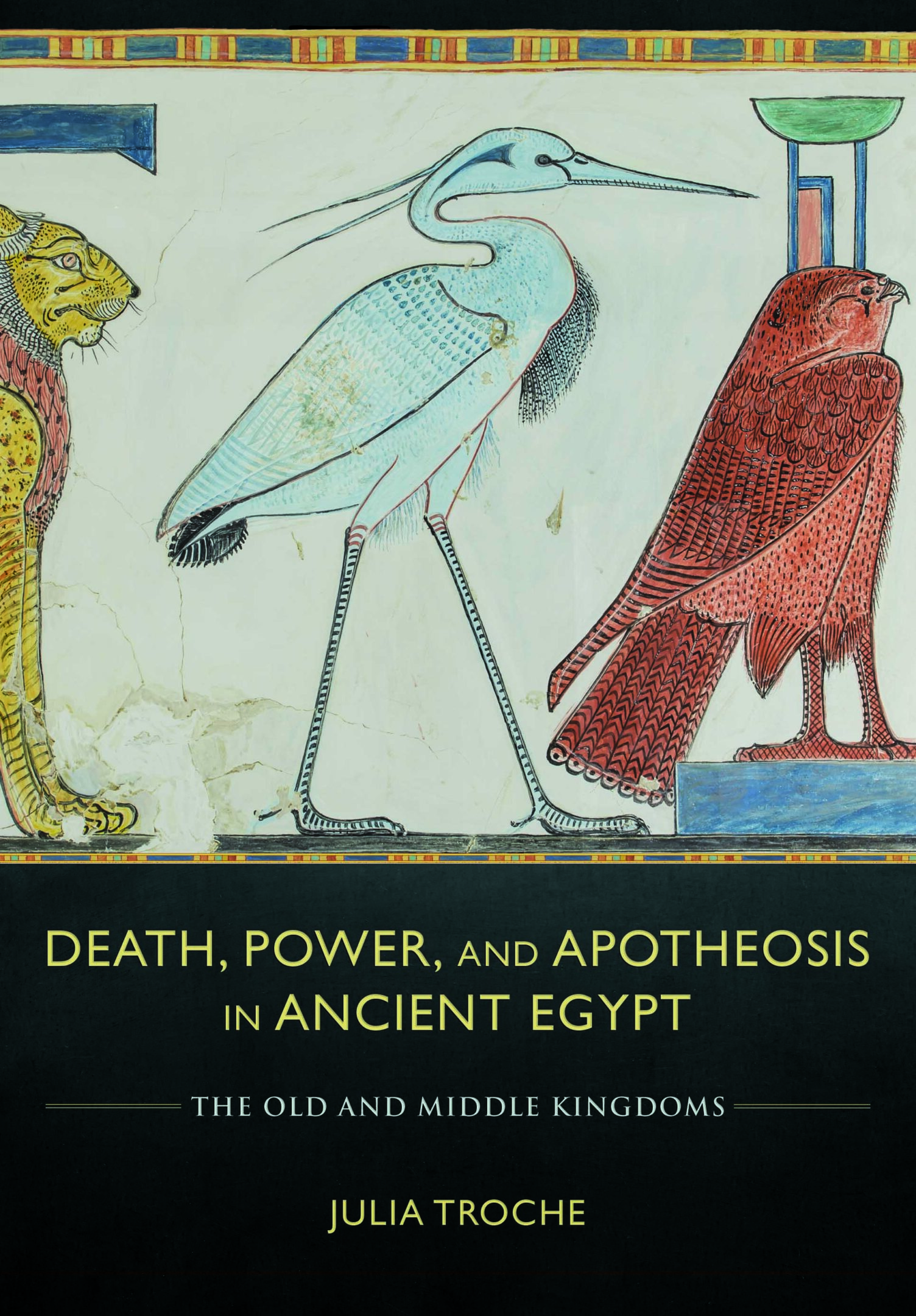

Treating the dead like gods

Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms by Julia Troche

One of her main research areas examines the intersection of religion and society in the ancient world.

“This involves thinking about how religious and social practices, norms and ideology confronted each other or worked together,” said Troche, an assistant professor of history at Missouri State University.

Her latest project is her first book titled, “Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms.” It builds on her dissertation research about glorifying the dead in ancient Egypt (around 2700-1650 BCE).

Drawing from resources like ancient inscriptions, artifacts and literary works, the book explores how ancient Egyptians created, kept and challenged power through:

- Mortuary culture – practicing specific rituals and giving offerings to the dead.

- Apotheosis – elevating the dead to god status.

Troche studied people during that era who treated their dead as gods – going beyond ancestor worship. She explored how they used their esteemed dead to negotiate social, religious and political capital.

“People were asking them to do things the normal dead weren’t asked to do such as ‘Can you get me into the afterlife?’”

She notes that was something only the king did before, and it challenged the king’s power and authority.

“These deified dead were now able to do things that were once reserved exclusive to the king,” she explained. “So, it’s this interesting power play.”

In Petra, Jordan, Dr. Julia Troche participates at an archaeology site.

Looking at power from both sides

A key goal of Troche’s research is to analyze and present information from a different angle than the way it has been taught or described in publications.

That’s why in addressing power in her book, Troche includes both top-down and bottom-up power. Instead of focusing only on the king’s actions, she also highlights what the elites and other Egyptians did.

“When we think about power, we don’t just look at the one in charge. We also have to think about all the other people – the subjugated others,” she said. “It doesn’t mean they don’t have agency and power because they’re subjugated.”

Exploring past and present pedagogy

Another focus area for Troche is on the practice of teaching. She researches “pedagogy both in and of the ancient world.”

“I want people to gain an appreciation for ancient Egypt and the ancient past, just for the sake of that ancient culture.”

Recently, Troche completed an article about virtual reality storytelling. It’s based on a collaborative project with writer and performer Eve Weston.

They created a proof-of-concept video game called “The Spirit of Egypt.” It uses virtual and augmented reality to teach about ancient Egypt through storytelling and humor. The game features the funeral of Hatshepsut, one of the most powerful female pharaohs.

In the article, which focused on using the game for instruction, Troche argues that modern historians can and should use nontraditional ways to teach and engage learners.

Dr. Julia Troche and Dr. Kathlyn Cooney, UCLA, pose with students at 2019 Nelson Atkins event.

“Humorous and quirky things may not be proper academic pedagogy. But they are useful teaching tools, especially for college students,” she said. “You help people learn better by engaging with the things they love.”

Another one of Troche’s recent collaborative efforts revolved around science fiction. This time, she worked with fellow Egyptologist Stacy Davidson from Johnson County Community College on a project about Star Wars’ Force ghosts. They compared the ghosts to the ancient Egyptian Akh – the effective spirit of the deceased.

“Since Julia’s an expert on the Akh, I wanted to know how similar or different it was to the ghosts,” Davidson said. “It was clear we could use concepts in popular culture to open up new avenues for research and teaching.”

They created a video of their research. This past summer, they presented it virtually at an international conference on sci-fi in ancient Egypt.

Troche notes using Star Wars as a teaching tool works because it’s accessible and popular.

“Many people are familiar with the series and feel strong emotions about it. You can activate and build on that knowledge and emotion,” she said. “Then, use that as a launching pad to talk about ancient Egyptian concepts like spirits, the afterlife and rebirth.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

The language of a common affinity

Now, people are developing new languages to discuss common interests on online platforms.

Dr. Kewman Lee calls these platforms “global online affinity spaces.”

“In these spaces, people with common interests communicate with each other across national borders and linguistic and cultural backgrounds,” Lee said. He is an assistant professor in Missouri State University’s reading, foundations and technology department.

Lee’s research on the subject falls into an area of study known as New Literacy Studies (NLS).

Scholars of NLS go beyond print literacy and pay special attention to the social context of communication.

Researching Korean pop culture

In his research, Lee observed a website called Asianfanfics.com. Here, Korean pop music (K-pop) fans write and share stories about K-pop icons and celebrities.

“Contributors create their own social language spontaneously. There is intrinsic motivation to learn the language to become an insider of the group,” Lee said. “It is quite similar to the history of the development of language thousands of years ago.”

The conditions for this modern, spontaneous social language creation are unique.

Imagine growing up in America and speaking English. If you moved to France, you may start to learn French. You might combine it with the language you already speak — borrowing words or grammatical rules.

“Standard English is standard for whom? In global online affinity spaces, participants create their own standard of language.”

This phenomenon is called “translanguaging.”

You can see a version of translanguaging in global online affinity spaces.

“English speakers use the translanguaging of English and Korean or the K-pop social language. Some Spanish speakers or Japanese speakers also mix their language using Japanese and Spanish words,” Lee said. “They’ve created their own standard of reading and writing.”

Kewman Lee stands with overlay of world map.

Diving deeper

Lee wanted to better understand the attraction to these spaces, so he observed three key components:

- How individuals create a unique social space online.

- What motivates them to become a part of the space.

- What processes they take to become an active member in the space.

Lee suggested that the motivation to seek belonging is the same whether online or in-person.

Lee’s paper on this received the 2021 Outstanding Paper Award from the American Educational Research Association.

Modern communication

The value people place on online relationships has increased drastically as online communication has expanded.

“One hundred years ago, the importance of an in-person relationship was 100%,” Lee said. “Thirty years ago, the importance was maybe 90% in-person and 10% online. Now, the importance of an online relationship could be greater than the importance of an in-person relationship.”

Because language is evolving with technology, the field of NLS changes to include new means of communication.

Dr. James Paul Gee, Lee’s mentor and well-known scholar of linguistics and literacy studies, was one of the early contributors to the NLS. He credits Lee with helping shape the future of the field.

“Kewman is a key scholar adapting the field of the NLS to a world where language, literacy and learning have gone digital and global,” Gee said. “He combines a solid grounding in traditional research with a wealth of knowledge about contemporary cultural practices across the world.”

Thinking ahead

Lee is just beginning his research into global online affinity spaces.

“Kewman is creating the future of areas that older scholars like me helped create but will not live to see fully unfold,” Gee said.

“K-pop is just an example of an attractor that prompted the creation of a global online affinity space,” Lee said. “My theory is that any kind of global pop culture could be an attractor of this phenomenon.”

Understanding this could be vital to informing how people develop technology, build relationships and support the education of future generations.

“There is a lot of global communication online that doesn’t quite fit into our standards,” Lee said. “But, as educators and literacy scholars, we have to open our eyes to new possibilities. We have to learn to understand new ways of communicating, including changes in how we speak, read and write.”

- Story by Rosemary Driscoll

- Photos by Jesse Scheve

Further reading

Military health: Detecting and controlling disease

He got the job of an Environmental Science and Engineering Officer. A broad role, it covered areas such as industrial hygiene, environmental health, vector control and food service.

“After doing all these things, I realized I’m a public health person,” said Thompson, associate professor of public health at Missouri State University. “The Army is the reason I got into human health. It’s been quite the experience and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

The military and the spread of diseases

Thompson has completed several research projects related to the military. One of them explored the movement of military personnel and its impact on global health. It resulted in a published book chapter.

For the study, Thompson looked at how military operations – both past and more recent – have contributed to the spread of diseases. These include vector borne, infectious and emerging diseases worldwide.

“The Army Reserves became a secondary career and compliments what I do at Missouri State. Doing the Army stuff keeps me engaged in the game and my knowledge base current on public health issues, and I can pass that on to students.”

For example, the flu pandemic that swept the globe during World War I was due in large part to troops moving around.

“When you congregate people, ship them some place and mix them with others, you can get large-scale outbreaks,” Thompson said.

In more modern times, large-scale outbreaks are rare. But Thompson notes that military operations have:

- Expanded the geographic distribution of many diseases. These include those thought to have been eradicated in a region.

- Led to the emergence of novel diseases.

Examples include cholera, malaria, pertussis, and leishmaniasis, which is a parasite disease spread by sandflies.

“We see things like bacterial infections you don’t often see in western hospitals,” Thompson said. “Because of blast injuries, shootings, and exposure to bacteria in combat areas, those have entered hospital settings. Some of them are antibiotic resistant.”

As military forces continue to move about for combat and peacekeeping roles, they spread diseases. Reducing the risk is key.

“These militaries can improve surveillance,” Thompson said. “It involves partnering with local governments and officials to improve their capacity and capabilities.”

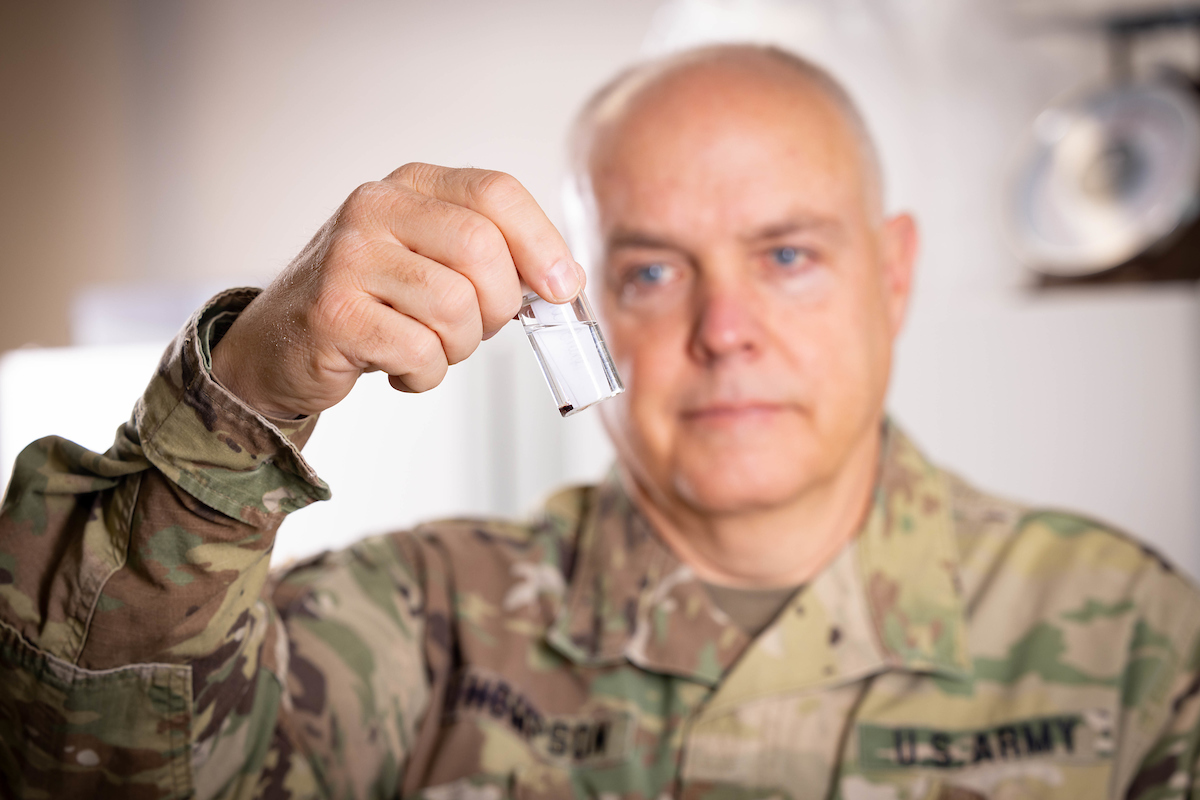

Dr. Kip Thompson values data to help predict and track possible outbreaks among military and civilian populations.

Studying data to predict an outbreak

When it comes to tracking and predicting diseases, data offers valuable clues.

Thompson points to the reports from each country’s local disease tracking system. During his deployments to Honduras in 2016-17 and 2018-19, Thompson received such reports weekly from the Honduras Ministry of Health.

“Public health in the U.S. tends to chase its tail. We’re not proactive, we’re reactive. I don’t know when we changed. We used to be more proactive and it’s probably a funding issue.”

He would track diseases of concern in his area and noticed a pattern. Each time he saw a gastrointestinal (GI) outbreak in the local population, an outbreak among service members soon followed.

“I tried to figure out, ‘was there a predictive component to that?’” Thompson said. “It turns out there was.”

As part of the medical unit, he was able to warn military personnel of the increased GI risk. He also shared reminders for preventive actions.

“You can’t always stop the spread of an illness, but we were able to at least reduce it,” Thompson said.

He’s completing a paper about the research for Military Medicine.

Public health expert Dr. Kip Thompson looks at how military operations – both past and more recent – have contributed to the spread of diseases.

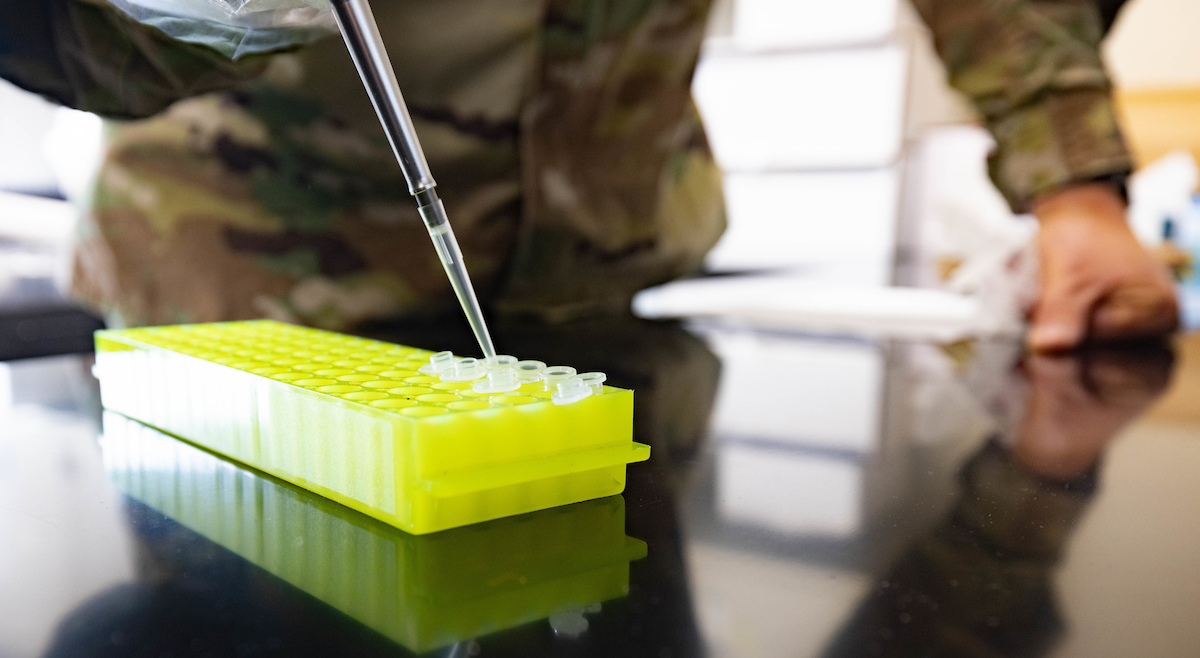

Controlling an outbreak with technology

Thompson has also delved into using technology to speed up the identification of infectious agents.

Service members who live in close quarters on base are at risk for rapid outbreaks of diseases like GI. To control them, quick detection of the cause is critical.

When Thompson was in Kuwait, his Preventive Medicine unit had polymerase chain reaction (PCR) capabilities. PCR enabled RNA or DNA sequencing to detect the pathogen of an outbreak within hours.

Using the system, he and his team were able to quickly identify a GI outbreak caused by norovirus.

“Because of that, we were also able to reduce the disease burden,” Thompson said. “The incidence of disease was down 10 fold compared to locations with the same outbreak but without the system we had.”

He co-wrote an article about this study for the U.S. Army Medical Department Journal.

According to public health expert Dr. David Claborn, Thompson’s military health care expertise is crucial to the overall study of public health.

“The military can affect American citizens and international populations alike,” said Claborn, director of Missouri State’s Master of Public Health program. “The study of military health care is as applicable to the civilian population as it is to the military.”

- Story by Emily Yeap

- Photos by Kevin White