Are my students cheating?

That question looms over every teacher. With the shift to virtual learning due to the pandemic, some questioned if there was a way to prevent cheating at all.

Professors at Missouri State, Marshall and Kansas State universities are examining the issue of cheating, specifically, whether the conditions of the pandemic caused an uptick in academic dishonesty.

The original study

Eleven years ago, while working at Marshall University, Dr. James Sottile, professor in MSU’s counseling, leadership and special education (CLSE) department, conducted research to determine if college students were cheating. Then, he compared cheating in seated courses to that of online classes.

The results of the 2010 study showed that while some students were cheating, there was not a significant difference between the likelihood of cheating in person versus online.

“Everybody assumed people would cheat more online, but that wasn’t the case,” Sottile said. “If people are given the opportunity to cheat, they’re going to cheat. That’s pretty similar for being online or face to face.”

Data during the pandemic

Considering the changes in class delivery during the pandemic, Sottile, along with Dr. Bonni Behrend, also a professor in the CLSE department, embarked on a follow-up cheating study.

Not only did the pandemic present an interesting environment, but technological advancements over the past decade were also factors to consider.

“Classes that were traditionally brick and mortar now have this virtual component,” Behrend said. “When you’re forced into a virtual setting, you maybe don’t have the time or the capabilities to think outside the box about what students could be doing whenever you’re giving them a test.”

Sottile and his colleagues collected data through a survey like the one used in the original study. They added additional questions to gauge if students were more likely to cheat since the pandemic began.

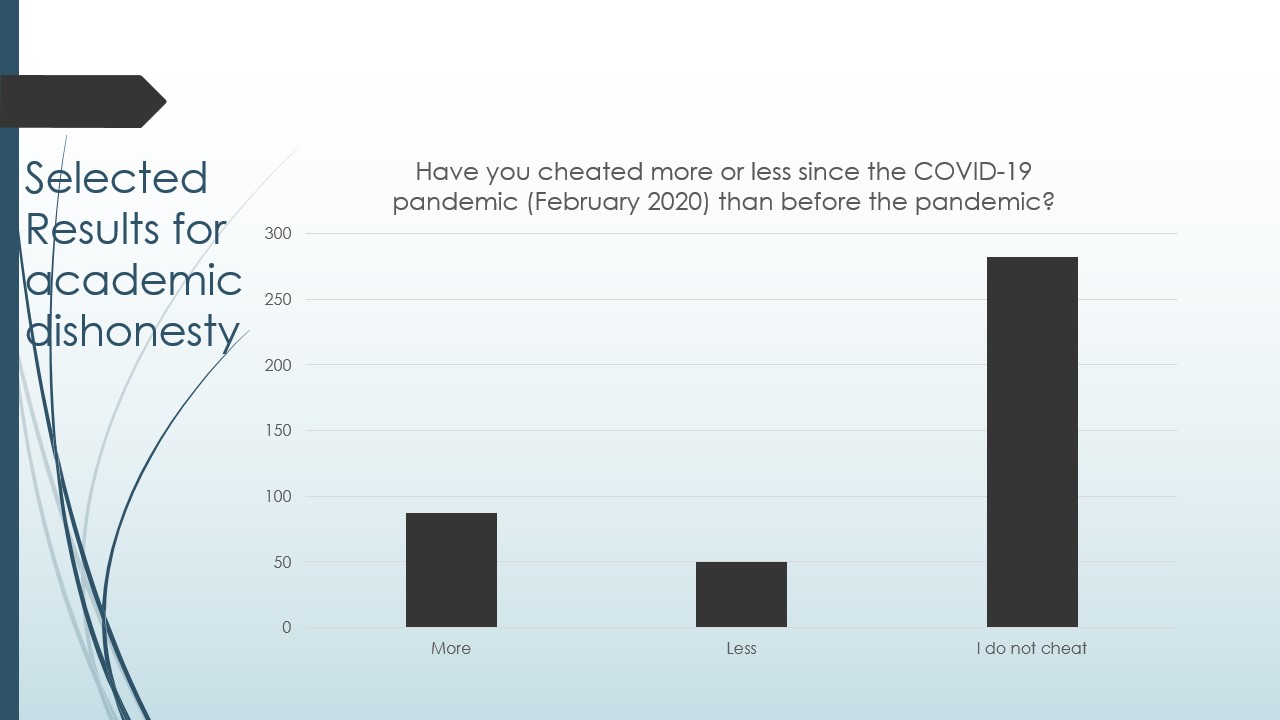

Survey results from 698 college student participants show that students may have cheated more during the pandemic.

Sottile, Behrend and their co-researchers will return to the study for a third time with more specific questions including:

- What percent of students in your live classes do you believe cheat at least once during the semester?

- What percent of students in your online classes do you believe cheat at least once during the semester?

They hope to narrow down their results to the most accurate depiction of what has happened during the pandemic.

“It needs to be also stated that a lot of people said they don’t cheat at all, and that’s good,” Behrend said. “But I think as we get more sophisticated with technology, our curriculum and the ways that we deliver education, we have to anticipate the needs.”

Addressing the issue of cheating

According to major psychological theorists, people who cheat are often motivated by how cheating will benefit them.

When it comes to academics, Sottile explained that the more competitive the atmosphere is, the higher the rates of cheating tend to be.

For example, the original research showed that:

- Graduate students tend to cheat slightly more than undergraduate students.

- Athletes tend to cheat slightly more than non-athletes.

- Men tend to cheat slightly more than women.

However, Sottile and his colleagues proposed that the solution is not to remove the competitive element. Rather, they would like to raise the moral standards students are held to in academics.

“The way you increase a person’s moral development, which is backed up by research, is to provide them with ‘what if’ scenarios and codes of ethics,” Sottile said.

Academic integrity at Missouri State

Sottile affirmed academic integrity policies in place at Missouri State are adequate if they are supported by teachers and administrators.

“I think everyone needs to be more aware of what we can do to prevent people from cheating, or decreasing the chances of cheating, as well as increasing a person’s moral development,” Sottile said.

Behrend notes the purpose of conducting research on topics like this is not to highlight the negative, but to acknowledge that there is room for improvement.

“People are going to cheat to meet a need,” Behrend explained. “We have to think about what we can do on the backside to be proactive about it as educators, as people who are educating the next leaders. At Missouri State, we talk about the public affairs mission in that way – how it helps to create greater thinkers.”